Eric Grayson, also known as "Dr. Film," jokes that he's delusional and has a severe problem with reality. He seems perfectly sane, but no one else in our area is fighting a battle quite like his: to collect, preserve, and curate old films, and place them in front of new audiences. His highest-profile projects have included the restoration of a Buster Keaton feature, and working with comedian Ernie Kovacs' widow to find lost films of her husband's.

Recently, Grayson traveled from his Indianapolis home to Bloomington to host a matinee of early stop-motion animation shorts at IU Cinema, where he spoke about the challenges of bringing to life films that some have given up on for dead.

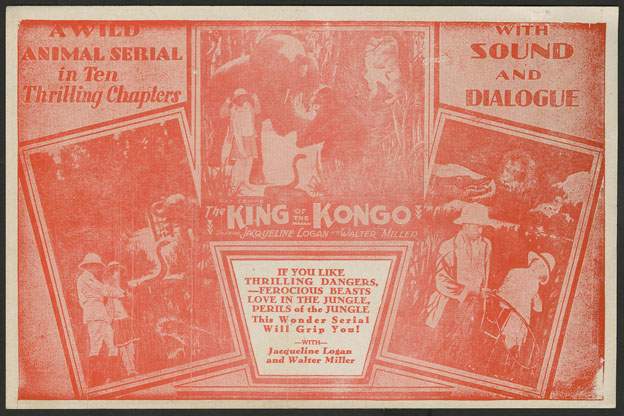

The most prominent film Grayson is currently in the process of restoring is King of the Kongo (1929). "It is a bad movie serial," he concedes. "And why would I work on that? Well, first of all, Boris Karloff is in it. Next off, it's the first sound serial that was ever made. So, you'd see 20 minutes of them every week and it would end on a cliffhanger."

Black-and-white is the kiss of death for people. They just will not watch it. That's like saying baroque music isn't worth listening to. You just have to understand a little bit about it.

What he saw on screen did put Grayson in a state of suspense – because the film had aged so poorly.

"It was preserved on bad 16-millimeter stock called DuPont, which is subject to vinegar syndrome and warpage, which means that it must be treated with camphor, which is a plasticizer. Unfortunately, the other bad thing about the restoration that needs to be fixed is that DuPont stock had very high contrast. So we have to scan this digitally, lower the contrast, and then clean up all the defects in the print, which are legion."

Clarifying the print was only part of the job. The original soundtrack, recorded on a series of 16-inch discs, needed to be found, one disc at a time. And then … mission accomplished, right?

"But the problem is they don't synchronize with the picture anymore, and so I've gotten a grant from the National Film Preservation Foundation to resynchronize these and make new film prints which are archivally stable – yea! – for the purpose of actually seeing this with the sound in sync with the picture for the first time since 1929."

Restoring the films is only half the battle. Grayson is also faced with persuading younger audiences to take an interest in old movies.

"What we're finding now is that anything that's more than three or four years old is like, it's this old movie that's really boring and why would anybody want to see it? And that's what I fight about, because I'm trying to expose people to films that they haven't seen, that are really cool, that are interesting, that have some historic merit. And I'm fighting the idea that they're old and stale and boring, and especially black-and-white. This is killer. Black-and-white is the kiss of death for people. They just will not watch it. And that's really sad because it's like saying baroque music isn't worth listening to. Well, that's not true. You just have to understand a little bit about it."

For the program at IU Cinema, Grayson focused on innovators in the world of stop-motion animation, including Willis O'Brien, Charley Bowers, and Wladislaw Starewicz.

"I knew this was going to be in their program for kids, and I knew it was going to be probably junior high and high school kids because you're not gonna get six- and seven-year-old kids to come to a movie show that has black-and-white stuff. So I programmed material that I thought would be visually interesting, little bit out there, stuff that they probably weren't gonna trip over on YouTube, and it was something that would make them talk to each other on the way home: 'This was fun! How was it I never saw this before?' That's the criteria. You say, if it's interesting enough that people are going to talk about it on their way home, that's what I want."