Myth: Palestrina's Pope Marcellus Mass Saved Polyphonic Music in the Catholic Church

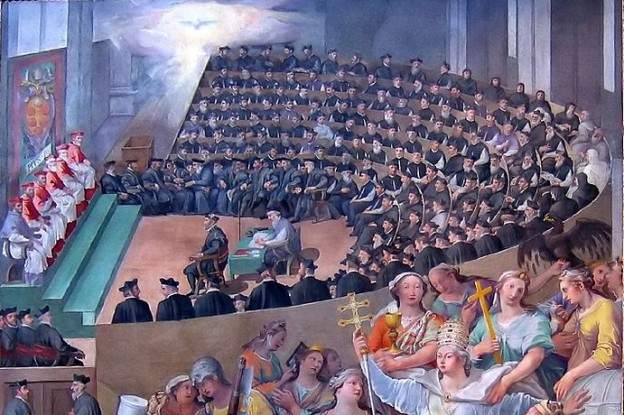

At the closing sessions of the Council of Trent (1545-1563), an important series of councils which issued condemnations and defined Catholic Church teachings, some debate occurred over whether polyphony should be banned outright in worship because the music obscured the words of the mass, interfering with the listener's devotion.

Starting in the late 16th century, a legend began that this was the impetus behind Palestrina's composing of his Pope Marcellus Mass in 1562. It was believed that the simple, declamatory style of Missa Papae Marcelli convinced Cardinal Carlo Borromeo that polyphony could be intelligible, and that music such as Palestrina's was all too beautiful to ban from the Church.

An entry in the papal chapel diaries confirms that a meeting such as the one described occurred, but no mention is made of whether the Missa Papae Marcelli was performed there or what the reaction of the audience was. This legend persisted into the 20th century. And composer Hans Pfitzner's even based his opera Palestrina on the story.

While Palestrina sympathized with many of the Council's decisions, and sought deliberately to compose in a simplified, easily-understood style to please church officials, there is no evidence to support either the view that the Council sought to banish polyphony entirely or that Palestrina's mass was the deciding factor in changing their minds.

Myth: A Jealous Antonio Salieri Poisoned Mozart

Why would anyone accuse Antonio Salieri, a respected court musician and opera composer, of the murder of Mozart? Maybe because he was the most convenient scapegoat. In the weeks before Mozart died it is reported that he believed he had been poisoned. The most likely candidate to Mozart was the Italian faction of the Viennese court. Soon after, people began to put two and two together and pointed the finger at the Italian Salieri. There are mentions of it in Beethoven's Conversation Books, Anton Weber heard the story and snubbed Salieri ever after. And Giacomo Rossini historically joked about it to Salieri when the two met in 1822, some twenty years after Mozart's death.

In 1823, Salieri is said to have accused himself of poisoning Mozart, although he was hospitalized and deranged at the time, and took it back at a later date. Even if few believed the ramblings of a confused old man, the fact that Salieri had "confessed" to Mozart's murder gave the rumor some semblance of validity. And this story was the germ of playwright Peter Shaffer's play and later movie, Amadeus, which almost single-handily perpetuates the myth in the mind of modern audiences.

Myth: Itzhak Perlman Finished A Concerto with Only Three Strings

In February of 2001, the Houston Chronicle ran a story which contained the following description of a recital on November 18, 1995 by famous violinist Itzhak Perlman:

Just as he finished the first few bars, one of the strings on his violin broke. You could hear it snap - it went off like gunfire across the room. There was no mistaking what that sound meant. There was no mistaking what he had to do. People who were there that night thought to themselves: "We figured that he would have to get up, put on the clasps again, pick up the crutches and limp his way off stage - to either find another violin or else find another string for this one." But he didn't. Instead, he waited a moment, closed his eyes and then signaled the conductor to begin again. The orchestra began, and he played from where he had left off. And he played with such passion and such power and such purity as they had never heard before. Of course, anyone knows that it is impossible to play a symphonic work with just three strings. I know that, and you know that, but that night Itzhak Perlman refused to know that.

A wonderful story. The problem is, Itzhak Perlman gave no concert that night, in Avery Fisher Hall or elsewhere. He did perform a concert two days later on November 20, which was reviewed in The New York Times, but it contained no mention of such a fantastical occurrence, which surely would have warranted inclusion in the review. Perlman played several other concerts that year in Avery Fisher Hall, but no reviews make any such assertion.

There are well-documented cases of other violinist performing with only three strings, and Perlman did at least once break a string during a public performance which was documented, but in that case instead of carrying with only three strings, Perlman filled the time with a bit of stand-up comedy while an instrument was prepared for him.

Myth: A Deaf Beethoven Kept Conducting at the Premiere of the Ninth Symphony

Here's the story: Beethoven, now stone deaf, was conducting the premiere of his famous Ninth Symphony. At the conclusion of the final movement which contains the groundbreaking "Ode to Joy" he was unaware that the music had come to an end and continued to conduct the orchestra until one of the singers stopped him and turned him around to face the riotous applause from the audience.

Now this is partially true. Beethoven was indeed at the premiere, and by many accounts he was on stage somewhere, perhaps helping to indicate the tempos of the movements. And many reports indicate that a singer either turned the composer around or induced him to turn and acknowledge the appreciative audience.

The problem with this story is that as not only conductor but composer, Beethoven must have been acutely aware of the pacing of his own symphony, presumably having the score before him. Not even a beginning conductor could be so incompetent as to conduct past the end of his own composition, even if totally deaf.

Myth: King George II Began the Tradition of Standing During the Hallelujah Chorus

Audience members traditionally stand during a performance of Messiah's "Hallelujah"chorus. Legend has it that King George II was in attendance at the London premiere of Messiah, and the king was so moved by the opening of the "Hallelujah" chorus that he leaped to his feet, and since he was the king, the audience was compelled to stand as well.

The origin of the tradition is uncertain, but the custom started early in the history of the piece. The first documented case of standing occurred during the May 15, 1750, performance of Messiah at the Foundling Hospital charity concert in London. However, the first published explanation of the custom did not come till 1780, when people began repeating the anecdote that King George II had stood at debut of Messiah in 1743. But historians are not sure that the king even attended that performance.