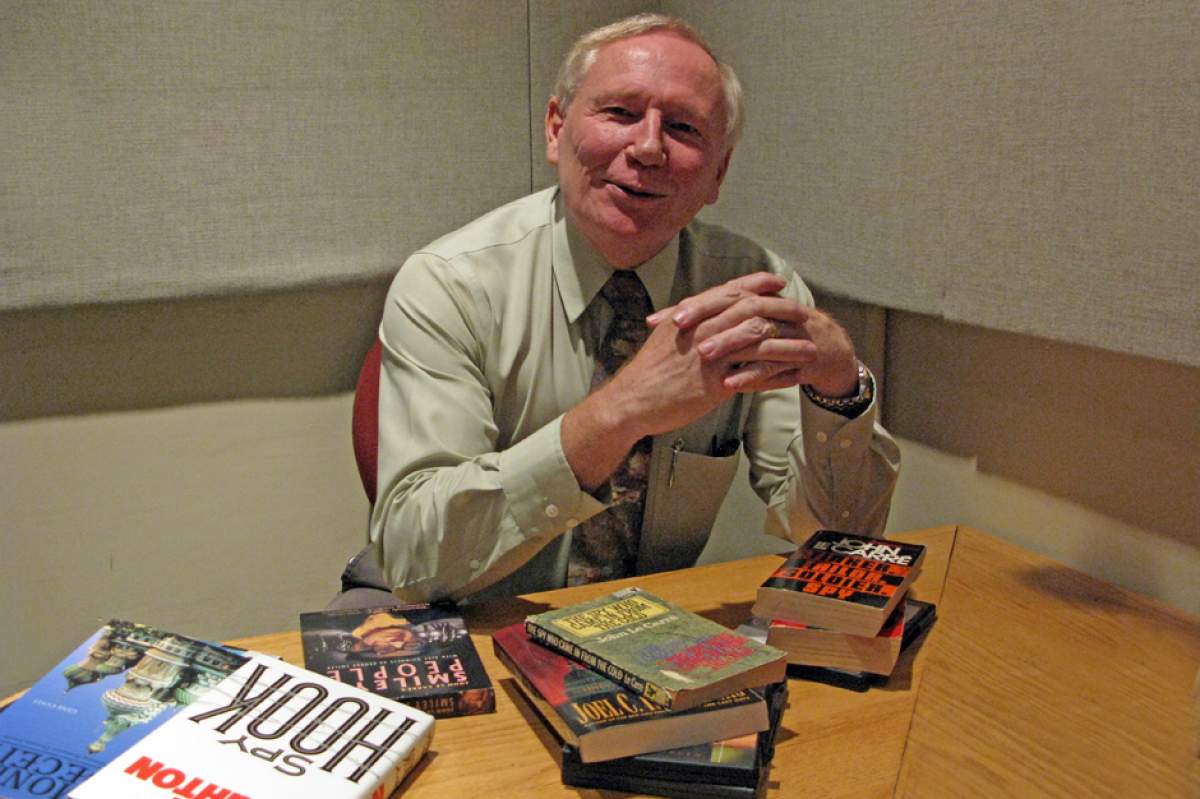

Gene Coyle is an Indianapolis native and IU alumnus who worked undercover for the Central Intelligence Agency for thirty years. Now retired, he teaches courses related to espionage at IU's School of Public and Environmental Affairs, the College of Arts and Sciences, and the Hutton Honors College.

Coyle also enjoys reading and writing spy fiction. He has written three spy novels: The Dream Merchant of Lisbon: The Game of Espionage; Diamonds And Deceit: The Search For The Missing Romanov Dynasty Jewels; and No Game For Amateurs: The Search for a Japanese Mole on the Eve of WW II.

Talking in a gravelly voice and sporting his Intelligence of Merit pin (awarded for an undercover operation he and his wife-also a retired CIA agent-performed in Moscow at the height of the Cold War), Coyle sat down with WFIU's Adam Schwartz to discuss the art of spy fiction.

Adam Schwartz: Do you ever put your real-life exploits into your novels?

Gene Coyle: Absolutely. But to get them cleared by the [CIA's] Publication Review Board, I have to change them enough so that the time frame is different, the country's different, or it's an amalgamation. Anyone who has been in the espionage business, and then tries writing fictional novels, you obviously draw on your past. I try to make mine as accurate as I can and still be entertaining.

AS: Have you ever thought of writing a non-fiction memoir?

GC: If I were to write a non-fiction book, it would be a major hurtle to get it cleared for publication by the PRB. If you write a fictional novel, it's a whole lot easier. You can take things that have happened in your career, or things that have happened to other people-you change the names, you change the country a little bit-and you can put it in a novel because it's now fiction. And the PRB signs off on it.

So, the three novels I've written, it's just a whole lot easier to call it fiction. Some of my friends have read them and they go, "Coyle, wait a minute. This is what you did in Lisbon." I go, "Shhh, shhh!"

A Good Yarn with Little Twists

AS: What are some ingredients of a good spy novel?

GC: You gotta tell a good yarn. And you have to make the characters interesting, so that the reader feels like they know them. What makes for a good spy novel-or any fictional novel-is if the characters in the story, by the end of the book you feel, "I've actually known this fellow." And you actually care what's going to happen to him or her.

And then I also like to build into mine-because I appreciate it in the classics-the little twists. The idea that you can have four or five lines of the plot going on and at the beginning you're wondering, "What this got do with that?" And then by the twenty-first chapter you go, "Aha." That is what sets a really good spy novel off from the hundreds that get cranked out.

An Intellectual Chess Game

AS: So you prefer the old-fashioned kind of spy novel that's like a puzzle you figure out as you go along.

GC: Well . . . my job was basically to be overseas, meet foreigners, and find some with a reason they would be willing to commit espionage for the United States. . . . I always viewed it as an intellectual chess game.

AS: And that chess game aspect is what intrigues you about a good spy novel?

GC: Yes, I want to know what's inside the heads of people. Why they do what they do.

Desert Island Novels

AS: Who are some of your favorite spy novelists?

GC: At the moment I'm reading a book by Alan Furst, his latest, Mission to Paris. Like all twelve of his stories, it's set in the 1930s, World War II. There's intrigue, espionage, sex. Almost any spy novel has sex in it. I enjoy Furst's historical novels because he tells a good story about the characters, their problems and their weaknesses, and how they get intertwined.

AS: I asked you to bring along some of your favorite novels and I see you've brought two by John le Carré: Smiley's People and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy.

GC: A number of the books that I own are by John le Carré. If I had to be stranded on a desert island with just one book, it would be Tinker, Tailor, Solder, Spy. Most people in the business would say that's perhaps the finest spy novel ever written.

There's one author your listeners probably aren't familiar with. He's a Russian who uses the pseudonym of Boris Akunin. He's written eight or nine novels that have been translated into English. His hero, Erast Fandorin, is a combination of Sherlock Holmes and Bruce Lee. The stories take place in the 1880s up to the First World War. Even translated into English, they're quite entertaining.

Real Life vs. Fiction

AS: What are some of the differences between what we see in spy novels and the real life of a spy?

GC: In a movie you have to tell the whole story and wrap it up in two hours. In the real world, to first meet someone on the cocktail circuit, become their friend, they start telling you what they really think, till the day you finally ask them to spy for you, is generally six to eight months. If you tried doing that in a movie, everyone would be asleep.

His Favorite Spies

AS: Do you have favorite fictional characters in spy fiction?

GC: Sean Connery as James Bond and Alec Guinness as George Smiley. They're quite opposite: The most energetic thing that Smiley does is lift a cup of coffee. But you can practically see his mind working. Wheels within wheels within wheels-which is what goes on in the real espionage world.

Needed: New Bad Guys

AS: One of the spy novels you brought, The Last Jihad, represents the relatively new subject matter that spy novelists have been working with in recent years.

GC: Joel Rosenberg has written five novels set in the Middle East that are about counter-terrorism. They're more about flash-bang excitement [than the older spy novels]. All these writers, including le Carré, had the problem when the Cold War ended, of "What are you going to write about?" So you've got narco-traffickers, terrorists. . . .

It was interesting that after 9/11 for a number of years all of a sudden the CIA were the good guys in American literature, movies, and TV shows. Everyone was feeling so patriotic. We're a decade past 9/11 and I've noticed in TV shows and movies we're again creeping back to where the rogue CIA officer has been assassinating people, or smuggling tons of cocaine. The CIA has always been a favorite whipping boy for writers and screenwriters. [Laughs] You have to take that with the territory.

'It's all fiction, gentlemen'

AS: Do you use your novels when you teach classes?

GC: I use The Dream Merchant of Lisbon because I worked into the story the reasons people do what they do. It's amusing that almost every semester at the end of the class, three or four men will come up to me and say, "Professor Coyle, this book seems rather autobiographical. We're wondering, that shower scene with the young Russian babe. Did that really happen?" I smile and tell them, "It's all fiction, gentlemen, it's all fiction."

Gene Coyle is working on his first non-fiction book, a collection of true stories about history's most ingenious espionage operations.

External Links:

The Dream Merchant of Lisbon: The Game of Espionage

Diamonds And Deceit: The Search For The Missing Romanov Dynasty Jewels;Â

No Game For Amateurs: The Search for a Japanese Mole on the Eve of WW II.