David Higgins sits at a drafting table in his airy office at the Musical Arts Center, working on a sketch of the opening curtain of the IU Opera Theater and Ballet Theater's production of Sleeping Beauty. His pencil moves swiftly around the paper with the skill gained from a lifetime of drawing.

Higgins' set for Sleeping Beauty will be his last for IU. After four decades of dazzling audiences, Higgins-master scenic artist, costume designer, teacher to generations of IU students, and last of a breed-is retiring.

"I'm not depressed about leaving," he says. "I'm not, umm"-he searches for the right word-" nostalgic. Well, a little nostalgic."

To recognize his contributions to more than 150 opera productions, the Jacobs School of Music has published David Higgins: Tribute to a Master. The slim, near-coffee table-sized volume celebrates Higgins' talents as a designer, professor, and chair of the IU Opera Studies program.

The Man Behind the Beautiful Scenery

Tribute to a Master was co-written by Marianne Tobias, author of Classical Music Without Fear, and Timothy Stebbins, who worked with Higgins as a scenic artist for twenty years. Stebbins envisioned the book as a comprehensive snapshot of what Higgins has done "for opera, for the School of Music, for Bloomington."

In particular, he wanted the book to introduce to opera audiences the man behind the name in the playbill.

"We have patrons who come to the shows, who have been coming for forty years, during the entire tenure of David's stay here at the School of Music," Stebbins says, "but don't really realize what has gone on behind the scenes or who David Higgins, the man, is."

"What they see is the beautiful scenery on stage and the great costumes and they see the name in the playbill and it says ‘David Higgins.' But they don't really understand what goes on to fill an eight-hour day, day after day, 365 days a year, to make all of that happen."

Six Signature Productions

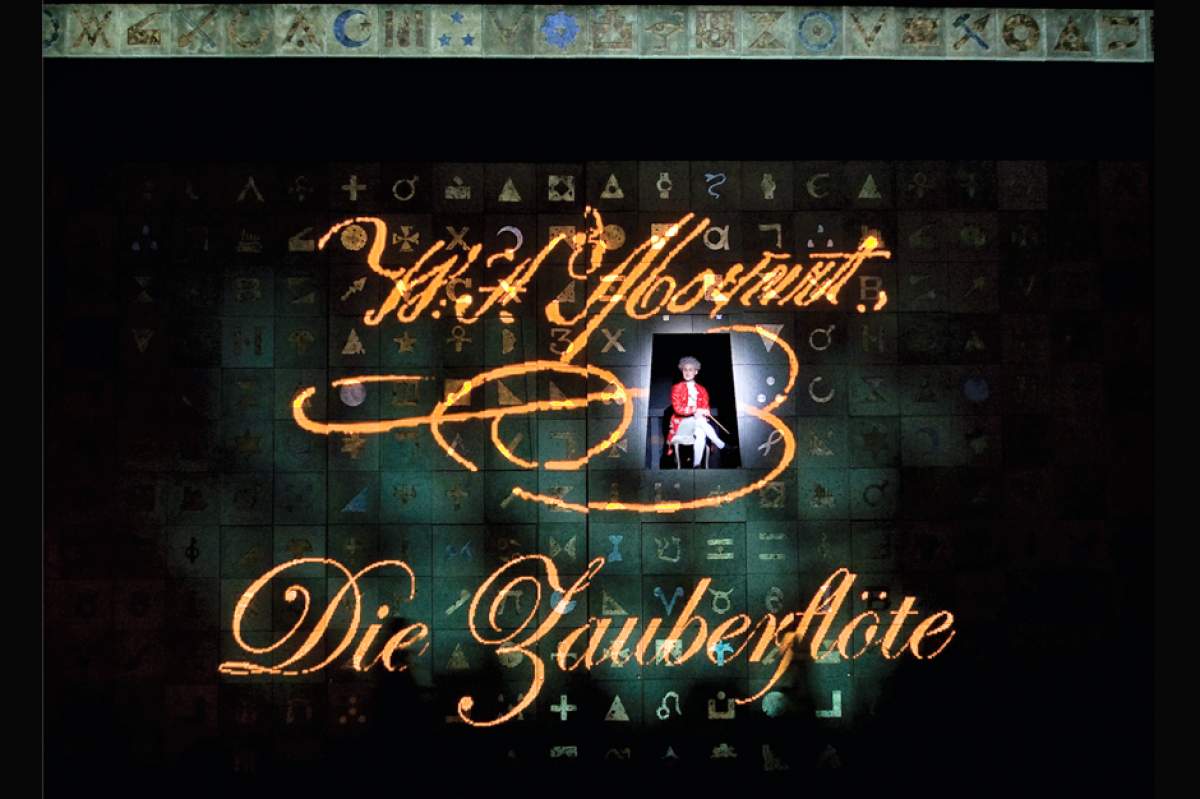

Stebbins and Tobias asked Higgins to pick six of his favorite productions for inclusion in the book. He chose his first main-stage production at the MAC, Fiddler on the Roof (1973), La Traviata, (1978), Das Rheingold (1983), The Nutcracker (1998), La Bohème (2007), and The Magic Flute (2009).

Each production is summed up in a single page, and throughout the book are forty color photos that attest to the elegance and grandeur of Higgins' designs. Reproductions of his sketches and blueprints for the productions provide further glimpse into his process.

Part of that process was Higgins' insistence on working in the European tradition-designing the costumes in addition to the sets.

"The logic behind it," Higgins says, "is when one person is doing both the scenery and the costume there is a seamless stylistic approach to the production. There is no opportunity to misinterpret where you're going with the visual elements."

Out of all his productions, Higgins is most proud of The Magic Flute. He wanted the production of Mozart's opera to be both sophisticated and fun.

"So we came up with this idea of a box. The production starts off with this wall of symbols from all different cultures-religious symbols, mathematical symbols, astrological symbols. And the overture ends, the box opens up and everything happens inside a box."

The Magic Flute was a hit with audiences, and with the regional opera companies to whom IU rented the show's sets. Higgins attributes the success of the production design to the way it appealed to all ages.

"I think a person who had never been to an opera before, could come to see that production and come away feeling that they had a rich artistic experience but were not overwhelmed by the seriousness of the work."

A Nutcracker to End All Nutcrackers

In the late 1990s, IU asked Higgins to replace the set for The Nutcracker that had been used for years, to create what Timothy Stebbins calls "the Nutcracker to end all Nutcrackers."

Higgins had previously designed some ten productions of The Nutcracker, and earlier had danced in it while studying dance as an undergraduate before he switched to studying scenic design. His goal was to draw upon those experiences to design a Nutcracker "that would be it," he says with a laugh.

"A lot of people consider the essence of my design to be Nutcracker and Bohème and Traviata and productions like that, big and beautiful, whatever ‘beautiful' means. That have a sense of"-he searches for the right words, and then chuckles softly-"shock and awe."

As Stebbins observes, Higgins' production of The Nutcracker is considered one of his career highlights.

"Here we are thirteen years on," he says, "and the show still looks great, and there's no discussion of replacing it at all. It's such an iconic production for us."

Putting the Grand in Grand Opera

David Higgins' style has been described variously as "romantic realistic," "boudoir scenery," "frou frou," and simply, "large."

"I often joke," he says, "‘You have to put the grand in grand opera.' I believe that the stage should have a sense of grandeur and a sense of spectacle."

Higgins liked his scenery to move. His set for A Midsummer's Night Dream featured a forty-eight-foot diameter ring that circled in one direction, while a smaller ring inside it moved in the opposite direction.

"I like for the scenery to be a character," he says. "When the scenery moves, when the scenery's kinetic, I think it adds a layer of interest and excitement to the production that static scenery can't provide. Many of my productions move."

Teacher and Mentor

Standing in the Musical Art Center's warehouse-sized Paint Shop, Higgins looks around and says, "This is where I've spend most of the last forty years."

It was here that he taught scene design, design history, and scenic painting to hundreds of IU students.

Timothy Stebbins says his favorite section of the book is the one devoted to Higgins' legacy as a mentor and teacher.

"I was in fine arts for long time," Stebbins says. "I did two graduate degrees. But I learned more about art from David Higgins and working in the shop than I ever learned in my studio or in the classroom. Things about art, art history, perspective, technique, how to use one mark instead of ten."

Last of a Breed

Higgins' method of painting sets the old-fashioned way-by hand with long-handled paintbrushes-is gradually disappearing.

After he retires, the dynamic of the IU scenic department will change, says Timothy Stebbins.

"David was truly one of the last members of a certain breed of designer and scenic artist. You don't find scenic artists who paint the way David paints-the old Italian tradition of painting that he learned from Mario Cristini. He taught me. We passed it on to Mark Smith, who's now head of the department. But with each generation, it diminishes a little bit."

Future IU productions are likely to make increasing use of computer-generated backdrops and video projections. The IU Opera's new production of Albert Herring, for example, won't have any hand-painted scenery at all.

But Stebbins predicts a backlash, a return to the kind of handmade scenery David Higgins is known for. Because, he says, when people go to the opera, they want to see live theater, live people, and real scenery.

Buy the book C. David Higgins: Tribute to a Master here.