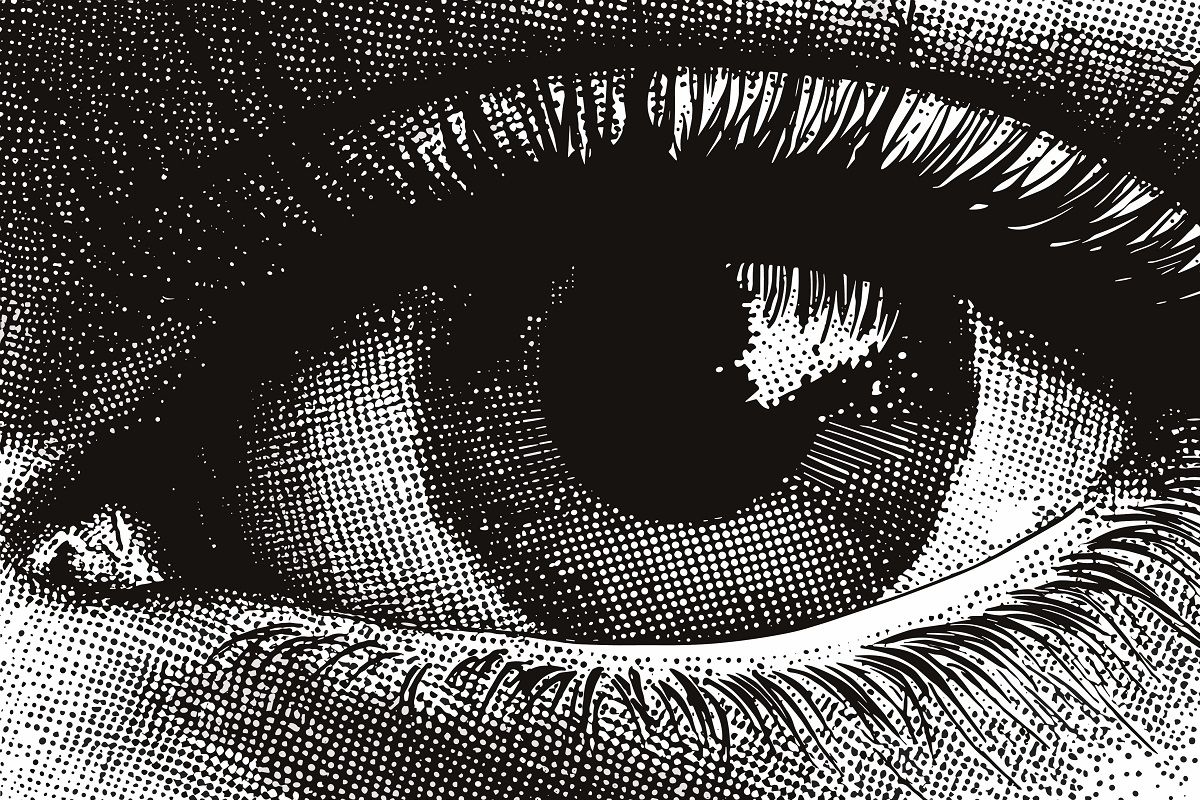

You may have heard that before you die, your life flashes before your eyes, right? Well, have you also heard that the last thing you see before death is recorded on your retina? While it isn’t true, it was a popular belief in the 19th century.

An image developed from the retina of a recently deceased person is called an “optogram,” Of course it sounds far-fetched now, but in the mid-1800’s, to a public just learning of the new technology of photography, it seemed plausible. After all, the “eye” and the “camera” are similar. Both have a lens. Both have a system for controlling light.

A scientist named Wilhelm Friedrich Kühne developed a process he said could fix the last image seen by a rabbit before death. The resulting image was highly questionable, but Kühne’s work was immediately applied to forensic science. If a victim’s last images were fixed permanently to the retina of the eye, would they convict their own killer?

An interesting idea!

Forensic optograms were used in famous criminal cases of the time, including Jack the Ripper in 1888. Even as late as 1914, a US grand jury viewed a forensic optogram as evidence in a murder case, though the suspect was not convicted.

While optograms didn’t turn out to be fact, the pseudoscience was popular enough to show up in fiction, including a Jules Verne novel, the 1936 Béla Lugosi and Boris Karloff film “The Invisible Ray” and even the popular TV series, “Doctor Who.”

From laboratory to literature to cinema, for a century and a half, the mistaken notion of optograms has fascinated us.

A special thanks to this episode's reviewer, Douglas J. Lanska, Neurologist, University of Wisconsin.

More like this:

Sources:

Optograms and Fiction: Photo in a Dead Man’s Eye, DePauw University Archives

Retinal Optography: Fact or Fiction?, American Academy of Ophthalmology

Finding a Murderer in a Victim’s Eye, The JSTOR Daily

Optograms and criminology: science, news reporting, and fanciful novels. In: Stiles A, Finger S, Boller F (Eds.). Literature, Neurology, and Neuroscience: History and Modern Perspectives. Progress in Brain Research, San Diego, CA: Elsevier Science