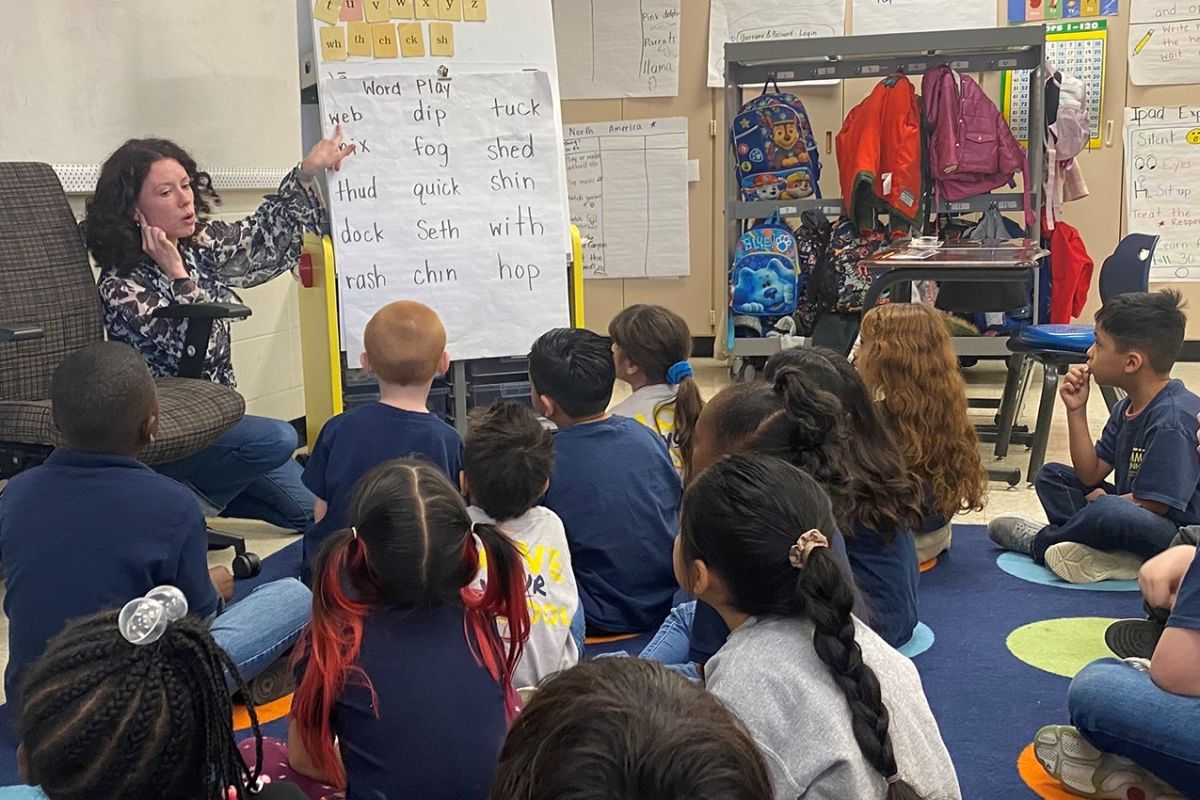

Teacher Ivy Sullivan works on reading skills with kindergarten students at Adelante charter school on Thursday, April 27, 2023 in Indianapolis. (Elizabeth Gabriel / WFYI)

Indiana is facing a literacy decline. Multiple state and national tests report young students struggle to learn strong vocabularies and phonics — the building blocks of reading.

And some educators say they’ve encountered middle schoolers who are years behind in reading and comprehension — these are the essential skills for learning.

All Indiana legislators banded together earlier this year in an attempt to combat students’ decline in the ability to read. They unanimously passed a bipartisan law that requires public and charter schools to adopt a new curriculum next year using reading science practices.

This follows an urgent push from state and business leaders. Gov. Eric Holcomb set a statewide reading goal of 95 percent proficiency for all third graders by 2027. A combination of state and philanthropic funds, now up to $170 million, are promised to support the changes in K12 through higher education.

Without the proper foundational literacy skills, educators say some students continue to struggle to read once they reach upper grades.

“This is not a new phenomenon, getting seventh and eighth graders who are struggling readers,” said Eddie Rangel, Executive Director of Adelante Schools in Indianapolis. “But [I’m] really happy to see that the state is taking action to say this is not just a school issue. This is a teacher preparation issue. And it's not just a kindergarten through second grade teacher issue. It is an educator issue.”

The science of reading is a collection of evidenced-based practices that provide educators with the skills needed to identify sounds and letter correspondence based on the way human brains process language. The practice still incorporates the five components of reading – phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension. Some teachers may already incorporate some of these strategies, but not all of them. While other instructors may apply them incorrectly or not all.

The new law, HEA 1558, reshapes how students are taught and educators are trained.

Starting in 2024, Indiana schools must adopt a new literacy curriculum that aligns with the science of reading. And educators will no longer be able to use popular reading instructional methods such as three-cueing. This method allows budding readers to use pictures and context clues, or cues, to guess an unfamiliar word instead of using their reading knowledge to sound out a word.

Researchers have said when reading science practices are applied it provides students with needed foundational reading skills. And it makes it easier for educators to identify and address why a student doesn’t understand a particular reading concept.

Rangel, who founded the public charter in 2020, said when an educator and student uses the science of reading practices, it’s similar to playing an instrument.

“You are learning a code, you have to know what that code means for if you're an instrumentalist, where your fingers are placed, how you blow the air, all of that,” Rangel said. “And then you have to piece that all together into a symphony, or an orchestral piece. And that's a lot like what reading is and what decoding is.”

At Adelante, reading science doesn't stop at third grade, it’s a school-wide effort, Rangel said. Whether someone is instructing music or math, he said all educators should be a reading teacher.

In 2021, less than 7 percent of students passed the English part of the ILEARN exam. A year later, the pass rate jumped to 33 percent. But in just released state data, just 10 percent of third graders were proficient in English language arts.

Rangel said the dip in scores may be due to those students who were impacted the most by the switch to remote learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic and other disruptions, such as attending most of first grade virtually. He said the school also hasn’t had enough time with the science of reading model to see extreme results across the board.

“In my experience as a school leader, change is going to take time, especially if we're expecting something to change and impact a school with a 10 percent proficiency increase after just one solid year of implementation, I think that would be very hard,” Rangel said. “ So I know, especially after data that we've been collecting in kindergarten through second grade, we know that the science of reading and the instructional practices aligned to the science of reading, are working and doing work.”

But the school, like many in Indianapolis, faces other barriers to boost student literacy and overall academics — especially as state leaders focus on a push for 95 percent proficiency for all third graders in four years.

Some of those include student mobility – students transferring from other schools — and supporting low-income kids who are behind grade level proficiency.

“This year we've got a lot of work to do because 40 percent of our third grade is new to us again,” Rangel said about the 2023-24 school year. “And there was no judgment on what their previous schools did, but there's no question — they're struggling.”

Indiana’s literacy problem

A lot of Hoosier students struggle to read.

Nearly 1 in 5 third graders lacked fundamental skills needed to become a successful reader prepared to learn, according to the 2022 Indiana Reading Evaluation and Determination – or IREAD-3. The pass rate of 81.6 percent is nearly 10 percentage points behind the state's highest score of 91.4 percent in 2012-13.

And less than 33 percent of Indiana fourth graders were proficient in reading in 2022, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress. The assessment, known as the Nation’s Report Card, tests just a sample of students statewide. Of those tested, nearly 63 percent scored at or above basic proficiency — Indiana’s lowest rate in 30 years.

Some of the decline is because of the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted students and forced them to learn remotely. But in Indiana, kids’ reading scores have been on a downward slide for a decade. Researchers and educators believe there are multiple issues that contribute to this problem, including how educators are trained to teach reading.

The National Council on Teacher Quality recently released a report that analyzed nearly 700 college undergraduate and graduate teacher-preparation programs across the country. Only 48 programs — 39 undergraduate and nine graduate programs — earned an A+ designation for exceeding literacy experts’ for teaching reading science. The only Indiana school that received an A+ was Marian University, a private Roman Catholic university in Indianapolis.

Some of Indiana’s top four-year public institutions – such as Indiana University - Bloomington and Ball State University – received an F rating.

Jamey Peavler, a former Indiana educator and a reading instructor at Mount St. Joseph University in Ohio, said these colleges have been notorious for not producing a phonics and evidence-based teacher prep program for reading instruction.

“When you consider where our teachers and our schools are coming from and the training that they've had, there's no question why our literacy rates are so low,” Peavler said. “States where there are more teacher prep programs aligned to reading science and have been doing that historically, have different literacy concerns.”

MORE: Why this educator believes science of reading will help Indiana’s students

Proponents of the teaching method say Mississippi is proof. The state’s fourth-grade literacy scores have jumped from being the second-worst in the country to 21st in only a decade. The state credits the improvement to the state overhauling its literacy program to the science of reading. And some research is backing up this assertion.

Instead, some of Indiana’s top higher education institutions try to prepare teachers for any school environment by using a broad curriculum that focuses on teacher theories and pedagogy, Peavler said. But she also said that doesn’t give potential educators enough time to learn how to put those methods into practice.

“Most schools have choices about what curriculum they adopt, what their philosophies are,” Peavler said. “And so I feel like many universities probably want to play it safe, and just give this more generic introduction, and think that the curriculum will teach the teachers how to teach once they land in their assignment. And that is not accurate at all.”

Under the new law, the state’s accredited teacher-prep programs at colleges and universities must switch to a reading science curriculum. The law also requires educators who received their teaching license after June 30, 2025 to earn a state literacy endorsement in science of reading.

The IDOE will also review Indiana’s teacher preparation programs in 2024 to determine whether key concepts related to scientifically based reading instruction are taught.

‘A strong foundation’

Reading curriculum has shifted over the past few decades. Some adults might remember the days of the hooked on phonics reading model that used music to help readers. Teachers have also used picture clues to help students learn words that aren’t easily decodable and follow traditional letter sounds, like flour, pencil and phone. But that strategy isn’t helpful for kids learning how to read because they end up memorizing and then filling in the blanks, Peavler said.

Tina Cowan has nearly 20 years of experience teaching reading. She’s seen kids shuffle around to different schools, which makes it difficult for them to learn to read since there hasn’t been a consistent, foundational method for teaching reading.

Which is why Cowan is excited students will have a more consistent learning style across the state.

“You don't just start building the walls of a house, you have to have a strong foundation,” said Cowan, Adelante’s literacy specialist. “You can't just trust the ground, that's there, you have to make sure that its foundation is strong, or the walls are going to fall down.”

Cowan said students build their foundational reading skills in kindergarten through second grade, before they start adding more difficult reading elements beginning in third grade.

In kindergarten students learn letters and sounds by using picture cards that associate a letter, sound and key word together. Then students are taught using pictures, to make instruction geared toward all types of learners — students who learn using visuals, hearing or motion. Learning through motion means a student taps out a word with their fingers in order to blend the sounds of the word together.

But eventually, the pictures go away and some students can wind up lost.

“If they didn't get a strong foundation of understanding sounds, that these are letters and they have sounds, and then how those sounds start to work together,” Cowan said. “And then being able to decode the words, and then building up their fluency and their vocabulary to do the comprehension. If we're not building that foundation, then when they get to third grade, it just all looks like a code to them that they don't know how to decode.”

Cowan believes some teachers may have already implemented reading science practices, they just weren’t using that specific term. Now the politicization of the learning model could be leading to some skepticism.

Making the switch

Reading science has been making waves in the education community over the past few years. The recent debate around literacy curriculum has led authors of popular instruction methods to change their methods. Over the past decade, at least 31 states and the District of Columbia have passed legislation related to reading science. Indiana, Arkansas and Louisiana are the only states that have banned three-cueing, according to research by Education Week.

Over the past year, over 40 Indiana schools have worked with the Indiana Department of Education on a science of reading pilot, which included participation from the Logansport Community School Corporation in north-central Indiana.

Tami McMahan, director of English Language Learners at the Logansport schools, said she's’ seen a boost in literacy scores since making the switch to reading science practices three years ago.

“If they got to fourth grade and they're not reading and comprehending fluently, the purposes behind reading really shift when they get to those upper grades,” McMahan said. “And so then they're behind and you get frustrations, and then I think eventually it does impact students staying in school. With the science of reading, with that focus on helping those students read on grade level before they get to third grade, you're going to help negate that issue.”

She witnessed growth in non-English speakers who couldn't read, and believes all students could learn.

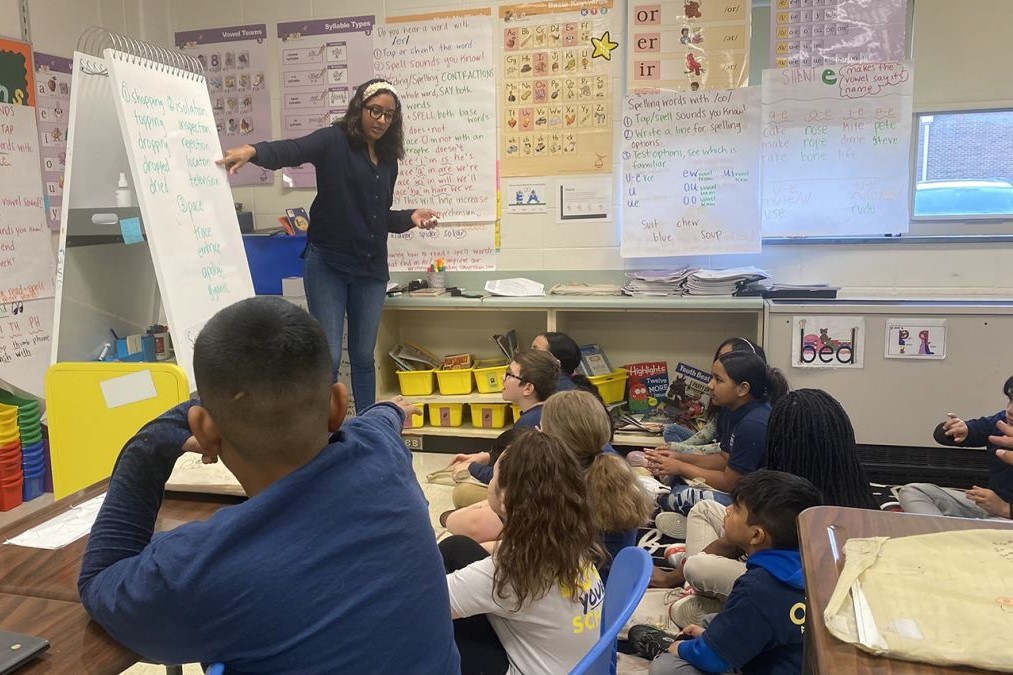

By implementing reading science practices, it also changed the way adults supported students. Teachers, interventionists and parents collaborated more, as well as administrators and other district staff who were trained to support teachers when they were struggling. As people were coming together, they knew they were on the right path. But there was some hesitation in the beginning.

“The beginning – it was rough. I'll be honest, there were some heels in the second at the beginning,” McMahan said. “However, they came on board, they gave it their all, and now that they're seeing the difference we don't have those issues anymore. Teachers are like, ‘Okay, we've got this.’”

Logansport’s literacy scores for English Language Learners went up nearly seven percentage points from 2021 to 2022. McMahn said their internal data has also shown reading growth across the district.

McMahan said they didn’t initially see the learning gains they expected, but they stuck with the process until it paid off. Now she believes other educators should do the same.

“It's scary as a teacher to think you know what, I've been doing this for 23 years and 80 percent of my kids learn how to read,” McMahan. “Okay, but what about that other 20 percent? What are we going to do there? And so that's a scary situation for them to switch their whole method of teaching, and just go out on a limb. So let them validate that feeling for them that yeah, this is scary, this is something new. However, we're going to support you.”

McMahan said they've always had an interventionist, additional tutoring and small group instruction, which is why they know it’s the science of reading that’s helping and not something else.

More teachers may soon experience the changes Logansport teachers experienced as educators adjust their teaching styles to align with the new law.

Contact WFYI health reporter Elizabeth Gabriel at egabriel@wfyi.org.