Indiana does not include suspension rates in its school accountability dashboard, making it difficult for parents to evaluate which schools are suspending students with disabilities most often. (Roman Bodnarchuk/Adobe Stock)

Bella’s school first suspended her in Kindergarten.

Five-year-old Bella had hit a teacher's aide and ran out of the classroom. A month later, the school suspended her after she tipped over a desk and fled the school. Eight days later, she was suspended again for defiance.

By December of last year, Bella had been suspended at least 15 times.

Bella is an outgoing kid, who loves to cook, talk on the phone with her friends and play soccer. But Kristin said the repeated suspensions affected her daughter’s mental health.

“She started questioning herself, ‘Mom, why am I so bad? Mom, I'm sorry. Why did God make me like this?’” Kristin said.

Bella has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, a diagnosis characterized by impulsiveness and difficulty focusing, sitting still and staying organized.

After the pandemic, out-of-school suspensions in Indiana increased to the highest level in a decade. Yet state education officials have not prioritized addressing the statewide increase in suspensions.

A WFYI investigation found that children, like Bella, who receive special education services were suspended more than twice as often from school as compared to their peers during the last academic year.

Federal law requires the state to track discipline disparities for students with disabilities. But the Indiana Department of Education has narrow criteria for identifying schools for review and it hardly ever intervenes.

This story is part of a series investigating school discipline in Indiana. WFYI spoke with more than 50 students, teachers, parents, advocates, attorneys and experts about the rise in out-of-school suspensions since the pandemic. In those interviews, parents of students with disabilities described how schools responded to behavior problems with repeated suspensions that added up to days — or weeks — of missed instruction.

Now in third grade, 9-year-old Bella is one of more than 22,000 thousand Indiana students with disabilities who were suspended last school year.

Kristin said because she has ADHD, Bella sometimes blurts out answers in class. She struggles to regulate her emotions. And when she gets in small conflicts Bella can meltdown.

WFYI is not using Bella and Kristin’s full names due to the sensitive nature of this story.

Behind Bella’s suspensions

Across Indiana, some school districts suspend students with disabilities at rates above the state average.

Bella’s school district in northwest Indiana — School City of Hobart — suspended children and teens with disabilities far more often in the wake of the pandemic. The district suspended special education students at a rate of 41 incidents per 100 students last academic year — far exceeding the state average of 25 per 100 students with disabilities.

Hobart Superintendent Peggy Buffington wrote in an email to WFYI that elementary-aged students are exhibiting more aggressive behavior, including choking their peers and throwing chairs, scissors and other objects.

“We seldom saw students exhibiting such behaviors at elementary ages as we have now experienced since the pandemic,” Buffington wrote. “We often learn these behaviors have been allowed to exist at home without prior interventions.”

But some parents say the problem isn't just student behavior — it’s how schools respond to it.

Kristin believes her daughter has been suspended so often because some of her general education teachers are not addressing her behavior appropriately. They get into disagreements over minor issues, and those conflicts spiral into explosive confrontations.

Take an incident from last year: Bella refused to sit in an assigned spot during class. Her mother, Kristin, said she wanted to sit by her friends. Bella argued with her teacher and threatened to hurt anyone who took her seat. When she went to wash her hands after snack, she was locked out of her classroom.

Then, Bella melted down. She knocked and yelled through slats on the classroom door. She crawled on the hallway floor. She shouted outside of other classes. She said she wanted to hurt herself.

The school called Kristin to come pick her up. When Bella didn’t immediately calm down, the school nurse called for an ambulance.

Kristin said she’d never seen her daughter so upset. “She just felt like nobody was believing her, nobody would listen to her,” she said.

The school suspended Bella for two days for defiance.

Why students are suspended

Students receiving special education services are often removed from school for behaviors linked to their disabilities — even though federal law is supposed to protect them from being excluded from school for actions related to their disability.

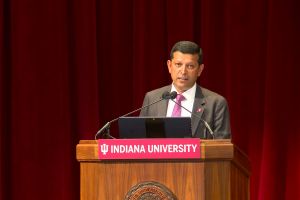

Sarah Hurwitz, a professor of special education at Indiana University, said that one reason why is because some disabilities go hand-in-hand with difficulty regulating behavior — like ADHD.

“They're doing impulsive things, they're hyperactive, they can't focus,” Hurwitz said. “If you understand that, then you can provide those supports, and then don't be mad at them when they blurt out something in class instead of raising their hand.”

Joe Kwisz, president of the Indiana Council of Administrators of Special Education, said there’s been a surge in violent and disruptive behavior among all students — including those with and without disabilities — post-pandemic.

Kwisz said outbursts can disrupt the school day for teachers and other students.

“So, if you clear a classroom of 22 children so one student can work through their episode that they are dealing with, then you've got 21 students who aren't receiving their education,” he said.

Kwisz, the executive director of Old National Trail Special Services, an organization that provides special education to several small districts.

“Do I think suspensions benefit kids? No,” Kwisz said.

But he said schools have to suspend students because they have limited options, especially when student behavior is violent.

“Even in our rural schools, I've had multiple staff members sustain serious injuries due to student interactions,” Kwisz said. “We've had multiple general education teachers injured. I myself have sustained a concussion.”

Due to concerns about educator injuries, Indiana is now tracking teachers and other school workers hurt by students on the job.

Several educators and experts told WFYI that schools are strained and they struggle to cope with challenging student behavior.

“We don't have a lot of the training or support I feel that is needed,” said Rebekah Raab, a special education teacher in Whiteland. “We don't really know what we need quite yet. We definitely are being stretched very thin.”

Raab said most of what she knows about how to manage student behavior she learned from veteran educators and behavior experts on the job.

General education teachers often get even less dedicated training in classroom management and student behavior than special educators.

Schools need to find the root cause of behavior

Indiana does not include suspension rates in its school accountability dashboard, making it difficult for parents and policymakers to evaluate which schools are suspending students with disabilities most often.

Federal and Indiana law offer protections to students with disabilities to ensure they receive a public education. If a school suspends a student for more than 10 days in a single school year, parents and educators must meet to discuss whether the behavior is because of the disability. If it is, the school is supposed to assess the student to find the root cause of the behavior and come up with a plan to address it.

Behavior plans often require educators to change their approach. For example, a teacher might give students choices. Or students might be allowed to take breaks.

Hurwitz, the IU professor, said a small minority of children with extreme behavioral challenges may benefit from a different learning environment outside the general education setting — like a self-contained classroom or a school that serves only students with disabilities.

“But for the vast vast majority of kids, even if they have a meltdown once in a while, there are behavioral reforms to try and keep them in their regular classroom,” Hurwitz said.

Advocates say that the federal protections have flaws. And they highlight one is that a behavior assessment isn’t required until a student is suspended for more than 10 days.

Bella was suspended repeatedly in the fall of 2024 — but she didn’t hit the 10-day threshold. In a report from a special education meeting in November, school staff wrote that Bella’s behavior was concerning, citing aggression and non-compliance. But they wrote that a “functional behavior assessment is not recommended at this time.”

Tom Crishon, chief legal officer at the Arc of Indiana, said if schools conduct more behavior assessments to understand what leads to students' outbursts — and come up with plans based on those assessments — they’ll suspend fewer students.

“Oftentimes, unfortunately we hear schools not doing those and they're resorting to out-of-school suspensions,” Crishon said.

Connecting with students

Experts say removing a child from school doesn’t address the cause of their behavior and often makes it worse.

“I don't think there's an easy solution,” said Catherine Voulgarides, an assistant professor of special education at Hunter College in New York City. “But I stand very firmly on the fact that decades of research show that out-of-school suspensions are an ineffective mechanism and typically will exacerbate the problems that are already occurring for individual students.”

In addition to training, Voulgarides said teachers and staff need to build relationships with students to understand the root causes of challenging behaviors.

“A key piece in that is time and human connection and sense of belonging between practitioners, families, communities, and students,” Voulgarides said.

That’s been true for Bella. In the first grade, she was suspended only once for behavior on the school bus — not in her classroom, according to school records. Kristin, her mother, said that’s because she had a general education teacher she trusted.

But earlier this school year, Bella was suspended four times. Kristin transferred her to a new school in the same district last October.

Now, Bella says she finally feels heard.

“They have much more help there for me. And when I have a lot of feelings, like they're there for me,” Bella said. “They don't just, like, assume that I'm in trouble or something. They actually let me talk.”

Bella hasn’t been suspended since she started at her new school.

Contact WFYI education reporter Dylan Peers McCoy at dmccoy@wfyi.org.