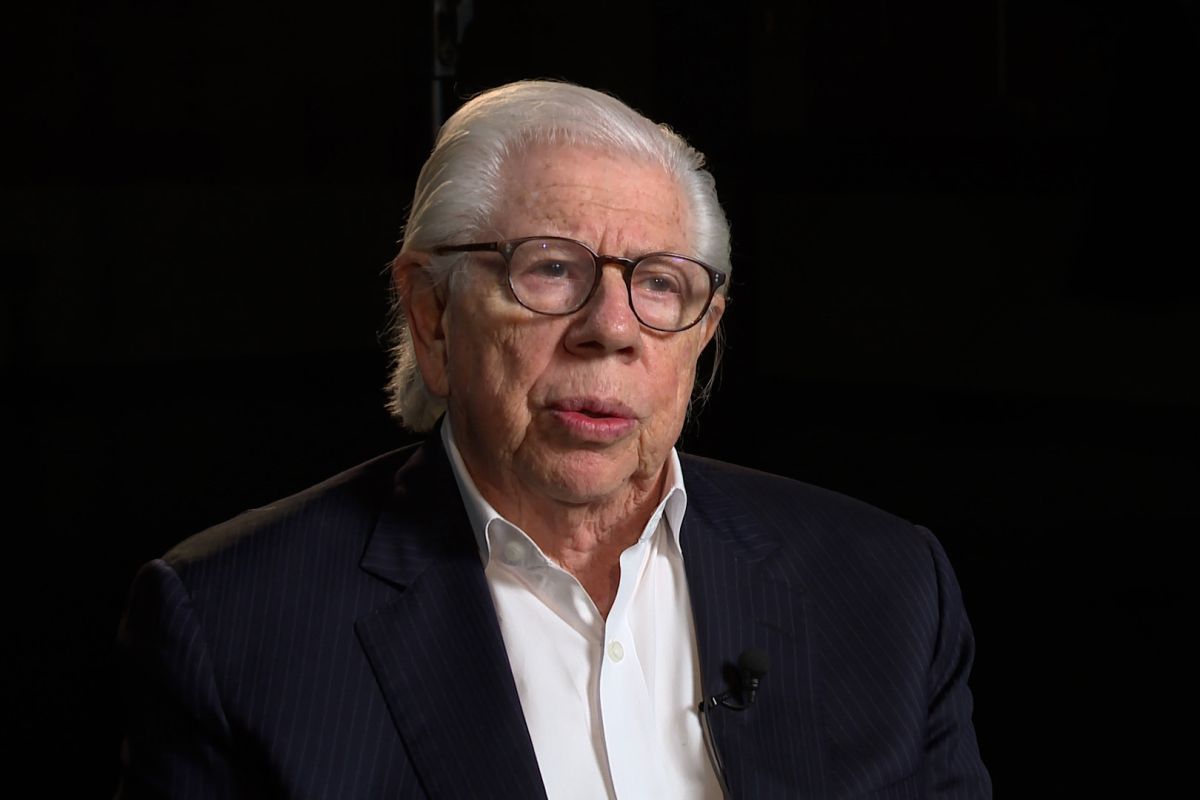

Carl Bernstein spoke with WFIU/WTIU News April 10, 2025. (Devan Ridgway/WTIU News)

Pullitzer Prize winning journalist Carl Bernstein reflects on the state of American democracy under Donald Trump’s second presidency with WFIU/WTIU's Ethan Sandweiss.

Read more: Nobel prize winner Maria Ressa on journalism and attacks on democracy

This Q&A was conducted on April 10 and has been edited for clarity.

You and your colleague, Bob Woodward, helped break one of the biggest stories in American news history, the Watergate scandal. You, of course, have also done numerous other investigations and written biographies of Hillary Clinton and Pope John Paul II, and recently, some memoirs of your own as well.

Going back to your experience reporting on the presidency, you said in the forward of the latest edition of “All the President's Men,” your book on the Watergate expose, that Donald Trump is the first seditious President of the United States, and that his actions leading up to Jan. 6, and on that day, constituted a threat to American democracy. Now we're almost three months into his next term as president.

Has your appraisal of Trump changed at all since then?

Only the degree to which recklessness figures in the equation.

As we're doing this interview a day after we almost had a financial collapse due to Donald Trump's recklessness, extraordinary event, the chaos of which we could see through the day especially, and continue to see with the fallout from what occurred, it's obviously something that is of great concern to members of his own party.

For the first time, we're seeing some real overt, not necessarily criticism, though there's some of that too, but real worry about his competence — not just his utterances, vengeance, seeking, et cetera, et cetera, that certainly has upset his political opposition, but now those who support him, particularly in the political class, and particularly in business, Wall Street bond traders, end up to have a disproportionate role here in taking him back from the precipice.

Even Elon Musk saying that this is an insane venture, this tariff seeking, in the 21st Century to re-order the world economic system of global globalization, and retreat back to the early 20th Century. We saw in one day the dangers of what he's been uttering.

What do you make of this sort of nostalgia politics that seems to be behind this kind of desire to retreat back to the 1950s and these various aspects?

Well, I'm not sure you're talking about Trump's desire to go back to the '50s. I think Trump's desire economically is to go back way before the 1950s; it's to go back to early in the 20th Century. It's about the kind of nostalgia for something that that he never experienced himself. It doesn't make any sense. You know, we have an established economic world order that has made the United States the envy of the world. It's consistent also with our role in the world as a leader of democracy in the world, he's repudiated that as well, and the two go hand in hand, though the repudiation of democracy itself and the role of the United States in furthering and leading the world in terms of what it means to be a free country, with institutions that are not governed by authoritarianism. We're beginning to see in his in his first 100 days that this really is an authoritarian situation in which we have never been in in our modern history in this country, and how it proceeds and how opposition to it progresses remains to be seen, obviously, but we are on the precipice there, too. So, we have both our economy and our basic fundamental identity as a free people who revere democratic means and institutions, both are on the line, and both are teetering.

There's also quite a bit of appeal, right? I mean, Trump has a lot of staunch supporters who seem to kind of support this vision of a return to something that's. More original. I mean, do you have any insider speculation into like, where this kind of desire comes from?

I don't do too much speculating, I'm really a reporter. But I think the important thing that we need to realize is that Trump's movement has tremendous depth in this country, that he has struck a chord with all kinds of people, and that basically half the country, in terms of adults of voting age, support and have continued to embrace, no matter how antithetical or outrageous his words and actions are, have continued to embrace him, elected him president with a majority of the vote - not quite the huge majority that he has claimed for this supposed huge mandate - but he has won the presidency, and his movement has changed us as a people, and whether we're going to go back is pretty doubtful.

Whatever develops we are in a new world, partly of his making. In that world, we are seeing the consequences of it already, the ugliness, the vengefulness of it, that is, we've already seen now in these 80 days. Whatever the exact number is, it's government by vengeance, by vengeance hate. It's right out there for all of us to see from the President of the United States to people he surrounds himself with. So, we're operating in a new theater here, and it's a theater. It's a warfare theater, and he is declared war on the old order as it was, not just dismantling what we have known in this country economically and in terms of human rights and our cultural and social progress as a country in the post war era, but going back before the New Deal, he is determined, and his he's made it very clear, to really deconstruct the world as we have known it in this country, and looking out from this country, from Back to the New Deal through the first quarter of the 20th, 21st century.

Talking more broadly about the context of free speech protest, especially before the Trump administration, during the last four years, and especially during the last year, there were protests on a lot of American cities, especially on college campuses against the war in Israel.

Some folks who participated in these protests had been arrested or retaliated against by universities, by police, and then also, there was kind of dialog in Congress, you know, in state houses that, you know, this was a sign of disorder, and this was there was something criminal about this speech. We've seen a little bit of a return to that in previous months, especially with international students who have had visas revoked at other universities because of speech they participated in.

Has the landscape of free speech, in your perception, changed significantly since the Trump administration has begun?

I think it's obvious and extends beyond just simple questions of free speech.

Trump believes in free speech for those on the side that he espouses and for opponents and those he disagrees with. His actions of a lifetime, but especially in these in these first days of his presidency, in terms of what he's doing in terms of universities and he does not believe in free speech. He believes in free speech for one side, and that is whichever position he advocates in, particularly when it has to do with Israel, when it has to do with what's going on in Gaza. Free speech for those who favor the position and actions of the Likud government and its partners in their policies in Israel, and a lack of free speech for those who oppose it and including expulsion from the United States of students from elsewhere who are not on the same side as he is.

On these questions, it's not really about the intimidation, the alleged intimidation, by these students, maybe in a few cases. There might, might be examples of that. And look also, anti-semitism is a real scourge in the world, in this country, on campuses, to some extent, but this is of a different piece. It's a kind of fig leaf for the way he deals with his opponents, generally, it's to intimidate them, to seek vengeance, to impose his beliefs and those of his movement on those who think otherwise. That's he is an authoritarian. He has begun an authoritarian presidency, and we see it particularly in the sweep of these executive orders, some of which might pass formerly legal tests, many of which would not have. And we'll see what the Supreme Court does as it proceeds through these various cases that have to do not just with speech, but with all manner of the way we live in this country and the way our government serves us or doesn't serve us.

And Trump has also taken a different approach to the press that might kind of reflect on some of these things that you've just observed about intimidation as well.

His method of dealing with the press also is intimidation at the same time.

I think if you look at the coverage by and large of his presidency, by most news organizations talking about legacy news organizations for the most part here that coverage has not been intimidated. It's pretty free flowing. It's pretty critical in terms of being accurate, contextual, fair.

Woodward and I have used the term “the best obtainable version of the truth” for more than half a century about what real reporting, real journalism is. I would say that by and large, that's what we have seen in these early days of the Trump presidency. I don't think we've seen any lack of wherewithal to go after the story, or willingness, for the most part, to be intimidated by him. And obviously there are draconian measures that he has advocated, and we'll see how they proceed through the Justice Department, through legal actions. He's filed lawsuits against news organizations; he indeed has the ability.

In some cases, we have seen capitulation by news organizations at the top in some instances, but in terms of what's getting on the air, what's being going out online, by and large, it seems to me, it's really serious contextual coverage aimed at being a truthful account of what reporters are witnessing and covering.

I assume you're referring to the CBS lawsuit, where Paramount is trying to reach a settlement?

One settlement. My colleague, Bob Woodward, he's sued for Bob his interviews with Trump, Bob and Simon and Schuster, his publisher put out as for commercial purposes. Trump has claimed that he owns it basically, and has sued Simon and Schuster and Bob Woodward. Look, his approach to life, going back to early in his career, is to sue people. He learned this at the knee of Roy Cohn, his mentor.

It's a vicious process, especially when those lawsuits are aimed at people that can't afford to fight them, which they have been historically, to some extent, in his businesses. It is a basic method of operation for him, intimidation has been the way he's dealt with people all his life and all his business life and to expect that we wouldn't see it after he's been elected to a second term of the presidency would be naive. I think what is perhaps surprising is the rapidity and the sweep with which he has used his authoritarian impulse and his methodology of a vengeful business person to deal with the nation, the world and people who might oppose his views.

I think it's fair to say when you were doing your investigation of Richard Nixon, that that you faced some intimidation yourself as a reporter. Do you have any advice for reporters on how to deal with intimidation when it's coming from above?

Well, look, we had threats. The basic response to our stories in the Washington Post from the Nixon White House and from the President of the United States was to attack us – Woodward, myself, Ben Bradlee, the editor of the Washington Post, then Katherine Graham, our publisher, to make our conduct, the conduct of the press, the issue in Watergate, rather than the conduct of the President and the people around him.

It worked for a good while, until the facts that we were reporting and the context and this best obtainable version of the truth that I've been talking about began to take hold in terms of readers and in the culture itself, that Nixon's crimes were becoming more and more apparent, but you know, Nixon remained quite popular for a long time into Watergate, it was a slow, slow process, and not until the tapes were disclosed, and some of what was on those tapes, did a majority of people in this country, if we were to look at the polls at the time, believe that Nixon should leave office, but making the conduct of the press a basic issue was a basic strategy of the Nixon White House to attack us.

Obviously, Trump has done this also as part of his methodology. He's also used the press very effectively, being a source for reporters, even having a false identity with the New York Post in which he was a source about himself and masquerading to get his own publicity. The forward to Bob's last book on Trump, which came out in October, is actually a tape recording that Bob and I did an interview with Trump in 1988 in a different context.

We ran into him on one day in New York, and he said, “Wouldn't it be something if you guys interviewed me?” So, we went to his office and sat down, and that interview from 1988 it is the prologue of Bob's book. You see the same Donald Trump. You see the same attempts. He says, you know, he likes to govern by fear. He operates by intimidation. He also tries to charm people, and can be, ostensibly, quite charming. So, we're seeing, you know, that same Donald Trump that we interviewed in 1988 we see today in in this. I keep using the word vengeful, but revenge is a huge element, not just revenge for his immediately past political opponents that he thinks tried to weaponize it to use his term, the instruments of governance, against him, but really a kind of vengeful attitude towards history, towards the history of our country, as I say, going back to the New Deal, all of post war, the Post War assumptions of who we are, what we have accomplished in this country, in terms of our economy, in terms of leading the world as a moral force, we've obviously faltered. We have no perfect record.

We certainly have had excesses of all kinds. We've had wars that we fought that we shouldn't have fought, all kinds of things that that did real criticism is is justified. We're looking at something different than simple criticism. We're looking at a different kind of ideology promulgated by a President of the United States who does not want to see in this country or elsewhere, the instruments of democracy leading this country or the world.

Going back to your own experiences again in the ‘70s and dealing with intimidation from the Nixon administration. Were there parts there where you felt like maybe the best obtainable version of the truth isn't enough, like maybe these attacks in our character would succeed and our reporting wouldn't bring about this kind of revelation?

I don't think we had any illusions that did our reporting was going to go to any particular place in terms of how it would resonate with readers, viewers, with people in the country. What we just tried to do was kind of keep our noses down and move forward on the story, and not and not be intimidated.

I'm going to tell a little story though, that to give you what the atmosphere was like.

Very early in our reporting, we did a story that said that Nixon's former Attorney General, his law partner, manager of his re-election campaign was was one of several people who controlled a secret fund that paid for undercover activities against Nixon's political opposition. And again, it's very important to realize that what Watergate was about was a vast conspiracy of political espionage and sabotage to undermine the free election of the President of the United States. This campaign of political espionage sabotage, was intended to actually pick the presidential nominee of the Democratic Party, George McGovern, and wipe out the more formidable candidates that Nixon did not want to run against, Senator Edmund Muskie, Senator Ted Kennedy.

And, so we wrote this story saying that John Mitchell, his Attorney General and campaign manager and close friend, had controlled the secret fund that paid for these undercover activities and put it in paper. And as Ben Bradlee said, there's never really been a story like this before, and it was kind of the harbinger of everything that was to come the real turning point in the coverage and the White House.

When I called the White House to get its response to the story, the spokesman for the White House said the sources of the Washington Post are a fountain of misinformation. And I said, is the story accurate? Did Mr. Mitchell control those funds? And he just repeated, the sources of the Washington Post are a fountain of misinformation.

We came to call that the non-denial denial. Make our conduct the issue, not Mr. Mitchell's conduct. And I had a phone number for Mitchell in New York, so I called and got him on the phone, and I wanted his response, and He said, “What does the story say?” And I read the beginning of the first paragraph to him. I got as far as John Mitchell, while Attorney General of the United States controlled the secret fund. And Mitchell said, “Jesus,” just like that. That exact tone.

And I read a few more words into the first paragraph, by which time, the drift of the story was unmistakable. And Mr. Mitchell said, “Jesus” got to the end of the paragraph, there was a pause on the phone, and Mitchell said, “Jesus Christ, all that crap you're putting it in the paper, if you print that Katie Graham” - referring to Katherine Graham, the publisher of The Washington Post - “is going to get her tit caught in a big fat ringer.”

I kind of instinctively jump back from the phone, a little bit more worried about my parts than Mrs. Graham's at the moment. And then another pause, and he said, “And when this campaign is over, we're going to do a little story on you two boys.” And he hung up the phone.

Sixty-five years I've been in journalism, it's the most chilling moment I've ever had. It was a real threat.

What it meant, whether meant physical harm, whether it meant attacking our credibility, continuing to make our conduct the issue in various ways, investigations, wiretaps, whatever, trying to. To take away the television licenses of The Washington Post company, which he led an effort to do to bleed the company dry of its profit. Just as it was going public during Watergate, he tried to get the Federal Communications Commission to strip the post of its of its television licenses. These were real threats of the order, almost of what Trump does in his threats. But Trump's threats are so draconian, let's look what he has said about what the Justice Department and his new attorney general are to do in terms of those who sought to use the system of justice in the January 6 case to try and somehow indict them put them in jail. We don't know yet, but he's certainly using all of these instruments for vengeance.

Recently, there was a signal group chat right between several members of Trump's cabinet planning a military strike in Yemen, and a reporter was added to the chat, stayed in the chat until he could verify that it was legitimate, then notified them of his presence and left and published a story about it. In this situation, how would you have handled yourself if you were that reporter who had been added?

I think that Jeff Goldberg of the Atlantic handled it brilliantly, responsibly. He did not disclose the national security secrets until the Trump participant in the conversation, and until it was really released by the White House, and in which it was also the assertion was made.

It really wasn't national security material. So at that point, Jeff Goldberg put out what was on his phone because it was determined to be benign by the Director of Central Intelligence in this in this instance. I think it was handled with great care and responsibility that what we see is a willingness to be reckless with national security secrets and information on a scale that we've never seen before, and then a responsible press doing what the government itself should have done to try and protect national security information. I think we ought to add to this equation that this is not an isolated attitude that we've done away the Trump people have done away with proper vetting by the FBI of people in national security positions who now have a free reign of looking at our greatest secrets and have not been properly vetted. There are dozens and dozens of such people.

Every day this administration is endangering our national security by eliminating the most basic of procedures to protect it.

I wanted to go back to asking some more questions about, you know, your early life and your early career as well. So if you grew up in Washington, DC, your parents were both members of the Communist Party.

Did these experiences in your childhood affect your approach to covering government?

I don't think so. My parents, like a lot of people, who were involved in an awful lot of civil rights activities, desegregating the capitol in the United States, Jim Crow town that I grew up in.

I went to legally segregated public schools in the capital of the United States until Brown v. Board of Education, 1954. I think maybe just coming from a politically inclined atmosphere in my household, I had an interest in politics in history, but in terms of ideology, about as on ideological as you can be, it seems to me that that's part of what being an open-minded reporter is about.

But like all the citizens, do I have a philosophy or that I basically believe in a framework, but the overarching framework that I believe in, and have since I went to work when I was 16 at a great newspaper, the conservative newspaper in Washington, the Evening Star, the afternoon paper, which was a better paper than the post.

When I went to work there, what I learned is this idea of the best obtainable version of the truth, which is what you see and you watch “All the President's Men” in the movie. You see these, these two young, 28, 29-year-old reporters going out and knocking on doors at night and trying to find out what happened from and make sources and the stories I've covered, whether it's Watergate or whether it's John Paul II, the Pope of the Catholic Church working with Ronald Reagan to undermine the Soviet empire. Whether it's that story, which was a huge story that really showed how the Pope and Reagan acted together to undermine communism, great tale, or whether it's a tale or a tale, or what happened in Watergate, or a biography of Hillary Clinton, which I've written - not a piece of work that the Clinton people, some of them took exception to some of it. Some of them thought it was really accurate. So that really, my beliefs are have to do with the power of reporting.

After Watergate, you wrote a piece called “The CIA and the Media,” which was about these connections between the CIA and reporters, some of whom you know worked willingly as intelligence assets. Could you talk a little bit more about that piece and some of the impact of that?

It's a very nuanced piece, the longest piece I've ever written. It was 25,000 words - the first piece I wrote after I left the Washington Post, because I'd gotten some hints about it and resulted in some congressional investigations and policies that the intelligence community would no longer use American reporters and American reporting organizations as cover for.

It was not about paid agents who were reporters. It was really about assets to use your term, reporters and news organizations that that had agreed to help the CIA in its collection of intelligence abroad, primarily. And Time Magazine and New York Times, CBS were among the news organizations whose leaders had agreed to do, to do this kind of collaboration with the CIA in particular. I don't think that it has continuedsince the story and since the investigation by Congress, to my knowledge, but I haven't done a deep dive to see if it anything like it has been resumed. But I don't believe that I've seen any evidence of it, or heard it, even, of any assertions of it. But it was part of the Cold War. You know, what better place to have a kind of cover than a reporter abroad during the height of the Cold War? So, it was a story that needed to be written, needed to be reported, and I was able to find a lot of information about it.

From the parts that I have read, some of these reporters who you interview, they don't see themselves as assets necessarily. They just see themselves as helping their country or having a positive relationship with their sources, right? How does a reporter keep that kind of like compass and know when they've crossed a line?

These relationships were pretty far over the line, it seems to me. Look, friendships develop between government officials and reporters. You try to keep a real separation and do your job, but obviously there's going to be some cross current in friendships at times, but you got to be really careful about about crossing a line and hopefully both people in a friendship, understand that. And we're not going to sit there across the dinner table and say, you know what I found out last week to somebody who happens to be somebody that we have a social relationship with, but you have to be careful about about how you conduct yourself in those terms.

When you came to IU in the fall and you sat on a panel and you had mentioned that the media as a whole had failed to report on Biden's mental state and the lead up to the 2024 presidential election. Do you want to expand on that at all?

I think one of the great historic failures of the press is the failure to adequately report on what reporters who cover the White House should have been covering, which is the president's apparent mental and physical decline, which they certainly had had a view of, and should have been spending more time on the story, and instead of attacking, as some reporters did, reports in right wing media that went to the question of the president's condition.

There was a cover up of Biden's mental and physical decline. It's a complicated story, but there was a real cover up by his family, by those around him who worked with him. There's plenty of accounts that in national security meetings, he was very sharp by most accounts. But there are other meetings, there are other public events, fundraising events at which he couldn't function effectively.

I reported that actually, after the debate about some 21 occasions that I believe was the number where he had had serious trouble functioning in terms of his mobility, a chair having to be brought over to him while he was in a fundraiser and was at a lectern and could no longer handle the physicality of the setting, but the basic reporting wasn't done. And you know what's the most important thing that a reporter or a news organization does in terms of the best obtainable version of the truth? It's to determine what is news. And there was a real unwillingness, I think, or reluctance on the part of those who were covering the president and the presidency at the time to go into this area. And I think history will not always show it, but the history of the country shows it as well, which is to say, doesn't mean that another candidate would have beaten Donald Trump, but certainly there would have been a different dynamic in the election had Biden not sought a second term, and that was really the question, and he decided to go forward and faltered mentally and physically.

Also, I think you know, some of Trump's characterizations of Biden are way over the Mark, perhaps in terms of the degree of debilitation, but I but we're talking about real debilitation, and it's an it's an awful part of the record of the press covering the presidency, and really stands out.

How would you compare that lack of coverage of Biden's mental state to coverage of Trump's mental state?

Well, again, I think, you know, the press has attempted to get to Trump's medical records with no success, really. I think there are fairly regular attempts to describe Trump as he is as he's seen, but I don't know what there is there. Trump tends to put out front, what-you-see-is-what-you-get very often.

But let me back up here a little bit about reporting on the psyche of a president. It's pretty much outside our reportorial wheelhouse, but in the case of Biden, there were numerous instances in in which mental lapses became evident. And I don't think we have seen similar mental lapses in on Trump's part, and yet, obviously, we have a pretty good look at whatever pathologies may be out there, but that's looking at apples and oranges here.

It's definitely not the reporter's job to diagnose.

Our producer had mentioned Trump's recent weaponization of the Justice Department to go after political enemies. You know, how does this compare to what we saw in the '70s with Nixon?

Well, we're early on. Nixon obviously went after his political enemies, used the IRS as an instrument, or attempted to have an enemies list.

Part of the Articles of Impeachment had to do with his misuse of his office to go after enemies, as it were, and as we mentioned early in the conversation, Trump has made it front and center that he wants to go after and prosecute those, including members of the press, perhaps, but certainly people who were in the Justice Department, members of the Biden family. You know, he's threatened an awful lot of people. He also is very clearly charged his Attorney General with this assignment of, I would call it, retribution.

He would call it use of the law to do what the law should do. I don't think there's much question of how retributive the assignment and the priority is in the first place. It's not a legitimate attempt to dispense justice equitably; it's a campaign. I keep using the word vengeance, and he's a vengeful person. Nothing new about this. And he goes after people and intimidates them, and sometimes he lets drop, sometimes he doesn't, but I've seen no indication that he intends to let these matters drop.

As somebody who is working as a local reporter — that's where you started yourself, right at the Evening Star doing local reporting — we talked a lot about reporting at the national level covering presidential politics. What does the state of local reporting look like right now? Is this something that's also threatened by a kind of new approach of the federal government towards reporters?

I think that the problems that face local news have much more to do with other factors than anything that has to do with Donald Trump over the last 50 years, and particularly the last 25.

We have lost in most towns and cities in America. Originally newspapers — even the succeeding online iterations of what were newspaper organizations — they've gone out of business in hundreds and hundreds of towns and cities across America.

That local newspaper was the cohesion that held communities together. It was the public square about high school sports results. It was about covering local government, feature stories on businesses and neighbors and as well as big cities as well.

I mean, here in Indiana, obviously, you had a couple major newspapers that no longer exist, chains like Gannett came in, bought up local newspapers shut them down. First, they stripped them of editorial content, and they became mostly advertising vehicles rather than covering the news, and they often entered into operating agreements with a second newspaper in the town or city, and eventually shut down one of the papers. And this is before the Internet became so prevalent that this started to happen, so that we have lost hundreds and hundreds of local news organizations.

And the other thing that that, you know, through the history of the country, or certainly the 20th century, most American homes had a newspaper on the breakfast table, and that included an AP report of what was going on in the world. I think there was a degree of news quote literacy that resulted from the existence in the daily lives of most people in this country.

And look at cities where you had three, four and five newspapers, so that the newspaper was a means of informing a whole populace that we don't have that today. But particularly what we've lost is local news. Local television news is notoriously commercial.

Local television news is notoriously sensationalist. We used to call it “lead and bleed.” Every once in a while, you'll run into a pretty decent local news organization. But by and large, including the network affiliates, it's not a very accurate picture in terms of the best obtainable version of the truth.

Does what you see in terms of what is news on local commercial news really reflect your community? I've asked the question hundreds of times, and rarely have I seen people raise their hands and say yes. But there are great things happening now, though, in terms of nonprofits that are that are doing local news.

The Texas Tribune, the most obvious example, which is maybe the best reporting organization in the state of Texas today, respected by thousands and thousands of readers and by people in the news business, of all kinds of political, ideological persuasions. There's been a lot of attempts now to take that model, that nonprofit model, and bring it to other cities.

We're also in an age when there's great investigative reporting going on all over the world, in this country, through nonprofits, through the few legacy news organizations that the major ones, whether it's New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, whatever problems people might have with aspects of the coverage of those three institutions, they continue. You to do some great investigative reporting, all of them.

So, I think, you know, we're in a period where we won't go to the question of social media, which is a whole other consideration, but in terms of stories meaningful stories, being developed by the old methodology of reporters knocking on people's doors, such as you see in the movie “All the President's Men.” What do you really see there? You see these people going out at night and talking to sources and getting the information. It's being done.

And the proof is in in the stories that that we read and see online, through streams, all kinds of methods of delivery of the news and of information. But it's there, and the work is being done. And magazines, both online and print editions, an awful lot of great reporting being done.