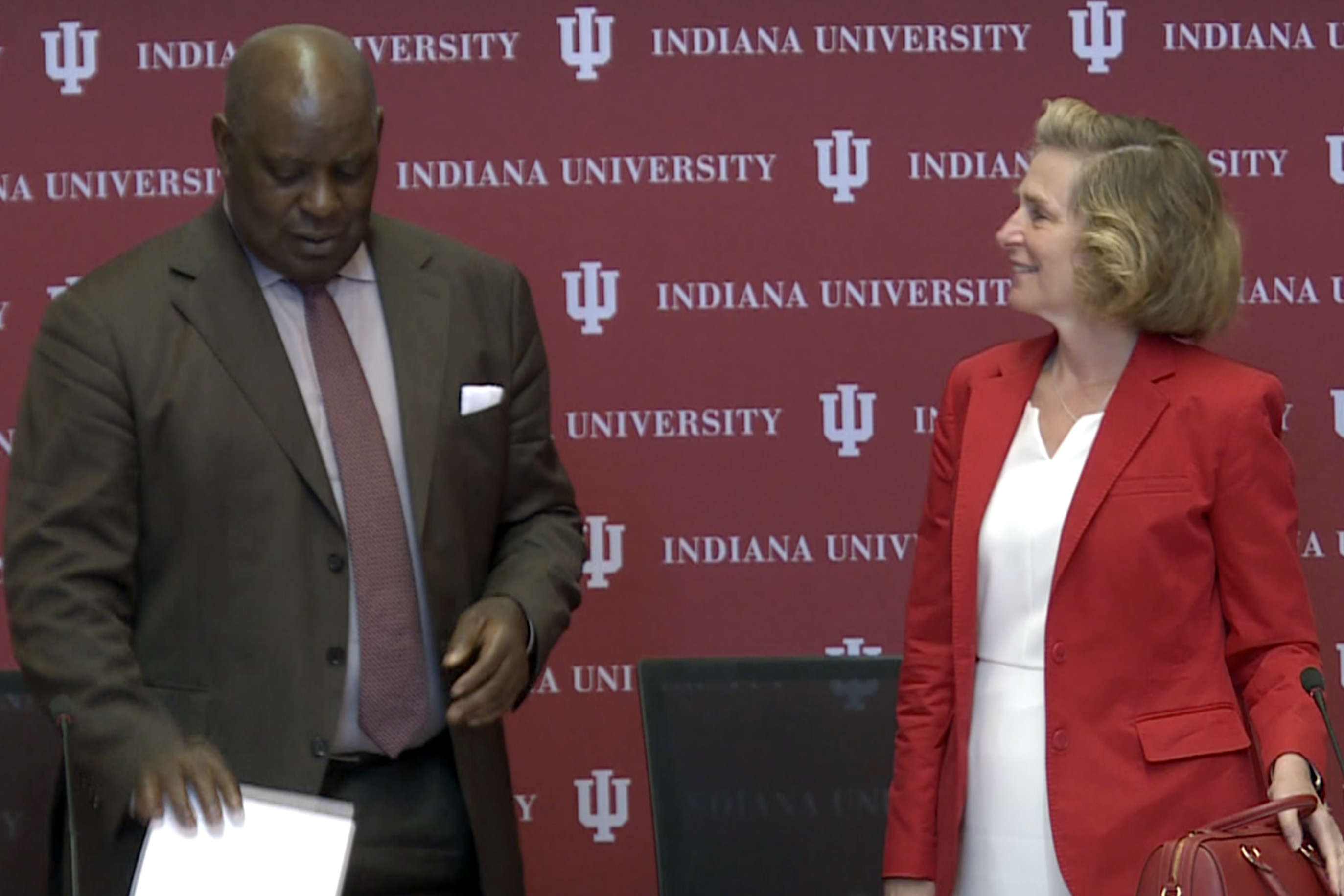

IU paid Cooley LLP $400,000 for a “post action review”, according to a summary on the university’s procurement website. (George Hale, WFIU/WTIU News)

This story has been updated.

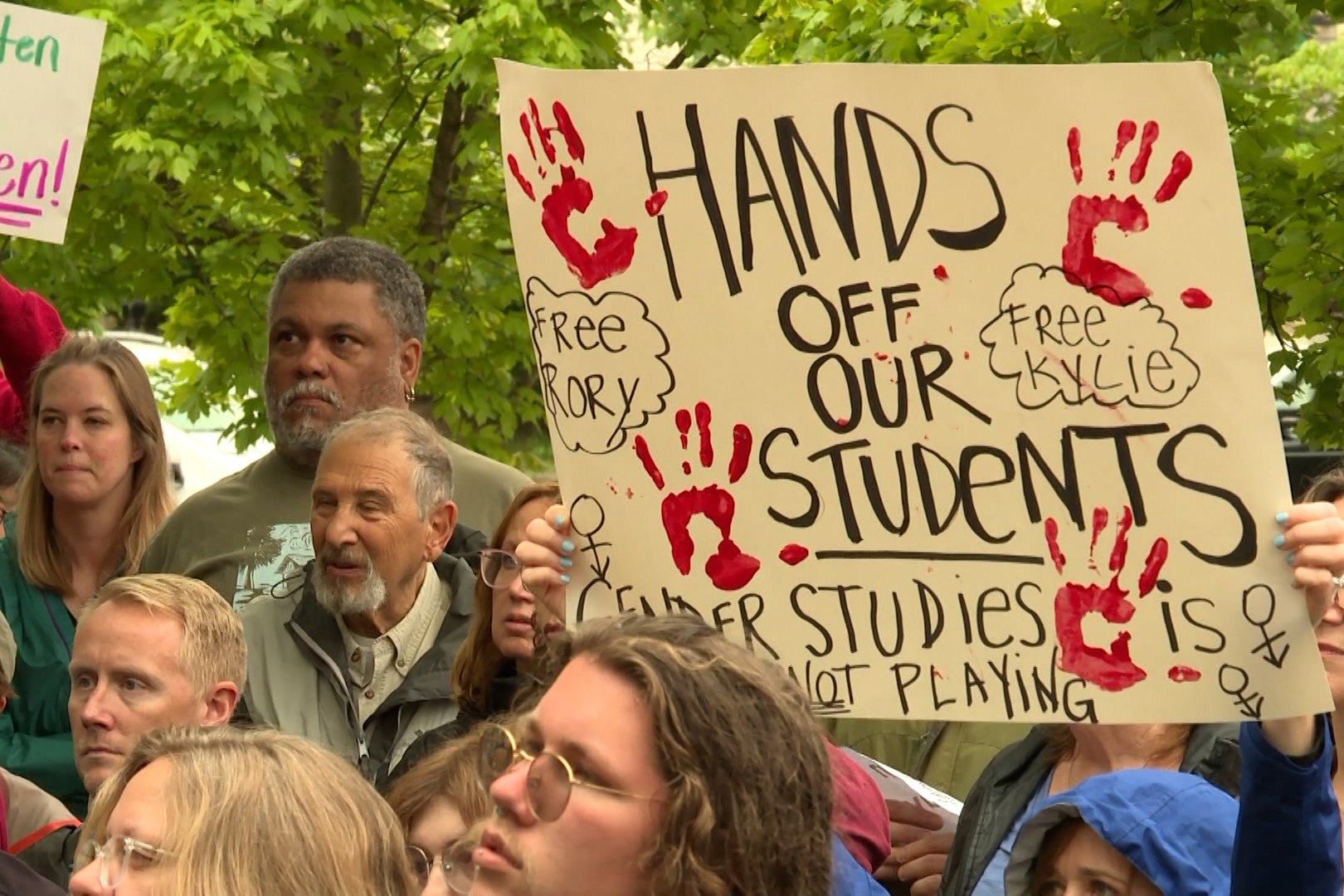

When IU leadership released a law firm’s review of the Dunn Meadow protests last week, it elicited both skepticism and vindication.

The 75-page report by Cooley LLP concluded that the administration’s response to pro-Gaza campus protests balanced free speech with safety, despite a volatile situation and unclear university policies, as President Pamela Whitten has asserted. It also recommended IU create a university-wide expressive activities policy and increase funding for the IU police department, both of which the university already planned to do.

Both IU and Cooley assert that the firm, which was hired by Whitten, acted independently and had sole discretion over the report’s content and findings. But critics on campus are unconvinced, pointing to the viewpoints Cooley chose to represent, how closely its recommendations align with the administration’s preferences, and the fact that the law firm’s clients are the same people it was supposed to investigate.

IU paid Cooley LLP $400,000 for a “post action review”, according to a summary on the university’s procurement website.

The investigative team details its research process in the report but not how it decided to direct the review. Still, it is possible to shed some light on those questions.

Issue of independence

The report’s critics include people involved in the protest, such as Professor Abdulkader Sinno, whose suspension from teaching for a room reservation error is covered in the report, and Bryce Greene, a spokesperson for the IU Divestment Coalition.

At a press conference in Dunn Meadow, both challenged IU’s assertion of the report’s independence, considering the administration hired Cooley to investigate its own actions.

“Anyone with millions of dollars can hire a bunch of lawyers and say that they did everything right,” Greene said.

“Pamela Whitten herself commissioned the independent review,” Sinno said. “It’s not her job, it’s the job of the Board of Trustees to do it.”

Donaleski categorically defended her firm’s independence, saying, “Cooley had sole discretion over the content of that report and the recommendations in that report.” Donaleski also said her team had full access to campus and university files, including more than 10,000 documents and emails, hundreds of hours of video footage and IUPD case reports.

IU law professor Steve Sanders, an expert on the First Amendment who has questioned the administration’s viewpoint neutrality in Dunn Meadow, has a more mixed reading of the report.

“Cooley is a very big, very professional law firm,” he said. “They’re not going to ruin the reputation by just doing a whitewash.”

On the other hand, Sanders questioned whether its analysis could be considered truly independent. “You know who's paying your bill, you know who your client is, and you're going to be critical of your client but you're also going to soft pedal it and be respectful about it,” he said.

Sanders added that, although Cooley may have worked to maintain its independence, the implicit biases of investigators could have affected the investigation. Its White Collar Defense and Investigations team, which ran the process, says it usually “defends companies and individuals in government enforcement actions.”

“I'm not condemning the report for that reason,” he said. “I'm just saying that is a bias that probably inevitably colors decisions that they made about who to interview and what analysis to provide.”

Leslie Lenkowsky, a professor emeritus at IU and member of the IU Faculty and Staff for Israel steering committee, said that it's difficult to prove independence for any investigation, using the congressional investigation of the attempted assassination of Donald Trump as an example.

"People will question that as well. There's no such thing really as purely independent, unless you found a man from Mars to come down here to look at it," Lenkowsky said. "But this is a good effort. If somebody wants to disagree with the provisions of the Cooley report, they're welcome to do so."

Cooley has weighed into the Israel-Palestine debate on campus before. In November it sent a letter with several dozen other firms to American law schools, saying they were alarmed by reports of antisemitism from campus protests, “including rallies calling for the death of Jews and the elimination of the State of Israel. Such antisemitic activities would not be tolerated at any of our firms.”

Choice of interviews

The report said investigators interviewed “more than two dozen people, including some more than once, for a total of 30 interviews.” Removing the named administrators, police officers and county prosecutor, that leaves up to 16 interviews for IU students, faculty and community members.

Cooley offered confidentiality and an open door to any student wishing to speak with them.

“We did meet with students from differing viewpoints across the campus, and we were very grateful that so many students, the vast majority of the students we reached out to, did agree to meet with us,” Donaleski said.

She didn’t confirm whether investigators spoke with protesters, saying she didn’t “want to go beyond what the students told us we could say.” She did say they interviewed students who had friends in the encampment.

Still, professor emeritus Russ Skiba of the University Alliance for Racial Justice questioned Cooley’s decisions on which voices to include in its report.

“It's important to note that the report is quite clearly not viewpoint neutral, having left out numerous key sources, such as the Monroe County Prosecutor's Office and the ACLU,” Skiba said. “It failed to interview any of the faculty members who were arrested.”

Arrested faculty confirmed to WFIU/WTIU News that they were not interviewed. It is not known whether Cooley interviewed any of the arrested students.

“They pass along some hearsay comments about how those people told the police that they were grateful that they were well treated or something like that, but it does not appear to me that they interviewed those people,” Sanders said. “I think that makes the report less complete.”

The document mentions that “some IU community members thanked ISP and IUPD for their professionalism,” citing one compliment IUPD received from a person who was arrested.

WFIU/WTIU News also interviewed one person arrested at the protest who praised an ISP officer who stopped pushing her when requested.

The report mentions one instance of Jewish students leaving Chabad House saying they were followed by a man shouting homophobic slurs who “appeared to come from the encampment.”

"To me the most sobering part of the Cooley report was the statement repeated on more than one occasion that people were choosing not to enroll at IU because of what had gone on there and because of the harassment that continues to go on in admissions tours," Lenkowsky said.

Protesters at the encampment have also alleged receiving verbal harassment and threats from passersby, although that isn’t mentioned in the report.

Cooley said it attempted to contact two of the protest leaders, but neither responded. Greene confirmed he was contacted by Cooley but that his lawyer “advised caution when talking with them and before we could finalize a plan or statement, the report was already out.”

The report said Cooley interviewed the Monroe County prosecuting attorney, although it doesn’t describe that discussion. Donaleski said that “reviewing the prosecutor’s decision was not within the mandate of what Cooley did.”

Read more: Prosecutor won't charge 55 arrested at Dunn Meadow protests

When asked about the ongoing ACLU lawsuit, she said she wouldn’t speak to any pending litigation.

State police involvement

Although the report said interviewees described the “ISP’s involvement and perception of their militarization” as a source of anger and frustration at IU, it concluded that calling state police was the “safest option for all involved once earlier efforts at de-escalation failed.”

The report lists several of administrators’ safety concerns, such as the potential for outsiders and unhoused people to move into the encampment or that it could “become a hub for potential assaults.” The report concludes that calling state police was reasonable, considering understaffing and lack of training at IUPD.

In the end, no assaults were reported at the encampment, although several unhoused individuals did set up tents in the meadow at various points.

Ultimately, Cooley said its investigation “did not include a review of external law enforcement’s conduct.”

It did interview state police leaders but said its mandate only extended to IU and that “those agencies are subject to their own internal review.”

Donaleski said investigators didn’t review ISP body camera footage for the same reason.

Sanders said Cooley did an admirable job assembling facts but that its decision not to consider the conduct of the Indiana State Police was a “major shortcoming of the report.”

“It seems to me that the conduct of law enforcement would be the central issue that you would expect to look at,” Sanders said.

State police coordinated with IU leadership during and leading up to the protest. In an interview with ISP Superintendent Doug Carter, the police leader described strategy meetings with Whitten on Wednesday before the policy change and ISP going into Dunn Meadow.

“President Whitten was the person in the room that was asking really tough questions,” Carter said in late April. “We talked about consequences, we talked about if we do A, what will happen to B, and if B occurs, what will C be?”

“The ISP clearly coordinated, sought instruction from and consulted with university officials,” Sanders said. “I think that goes a long way toward refuting that idea.”

The ad hoc committee and policy change

Cooley ultimately found that “IU leadership’s decision to change the Dunn Meadow policy was permissible under university policies and applicable legal standards, including the First Amendment; however, doing so the night before the planned encampment caused a number of unintended negative consequences.”

“I think they inappropriately took this at face value,” Sanders said of Cooley. “The idea that this random group of administrators that the Provost called together at 10:30 the night before the protest was the kind of committee that the Dunn Meadow policy envisioned – it was clearly not.”

According to the policy recommendations that led to the ad hoc committee’s creation, the group should’ve included the president of the IU Student Government and president of the Bloomington Faculty Council.

Considering the “late hour and time constraints”, the fact that IUSG “did not currently have a sitting president,” and that BFC president Colin Johnson was out of town and “known to be generally inaccessible at that hour,” Cooley reported that Provost Rahul Shrivastav instead chose Vice Provost for Student Life Lamar Hylton to represent students and Interim Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education Vasti Torres to represent faculty.

Johnson said administrators made no attempt to reach him on the night of the ad hoc committee. BFC bylaws say the president elect, in this case Danielle DeSawal, has the duty to substitute if the president is unavailable. Failing that, the immediate past president of the BFC is considered an appropriate substitute.

Johnson said nobody from Cooley reached out to him either, although they did speak with DeSawal.

The administrators were also incorrect about the IUSG president, which the report fails to mention. In fact, student government is never without one.

Under IUSG bylaws section 4-1-5 (c), the speaker of congress (in this case Abbey Miller) serves as acting president between terms. The IUSG has criticized the actions of the ad hoc committee and issued a statement on April 26 urging Shrivastav to reconvene it, this time with student government leaders included.

Then-president elect of the IUSG Cooper Tinsley didn’t say whether he was interviewed by Cooley but said he doesn’t believe the reasons administrators gave were enough to justify not including students in the ad hoc committee.

Recommendations

Cooley breaks down its recommendations into three categories: policies, security and communications. Many of them include plans the university had announced before the report was released.

A new expressive activity policy was already underway before Cooley recommended IU adopt one. IU Board of Trustees chair Quinn Buckner said “the Dunn Meadow report validated the need to update policies,” although the policy was released just one day after the report.

IU Faculty and Staff for Israel supported the revised policy.

"There were huge gaps and inconsistencies at the campus level at the university level with state law and even with some schools and departments," Lenkowsky said.

The Cooley report highlighted how those inconsistencies led to confusion requiring a new policy, he added.

"We are now starting anew with a policy," Lenkowsky said. "The one that we established 60 years ago is no longer very useful, and the new policy gets us off on a new start."

The report also recommends that the IU President should “direct a review for inconsistencies between university-wide and campus-specific policies and make recommendations to the Board of Trustees on necessary changes.” Trustees are responsible for passing some university policies, but so are faculty governing bodies such as the University Faculty Council and BFC.

Cooley recommended IU increase funding for the police department to hire more officers. Doing so, it said, would improve its ability to enforce regulations. According to IUPD Superintendent Benjamin Hunter, the department is about 40 percent understaffed, mainly due to uncompetitive salaries.

"The root cause of having the state police on campus was the underfunding of the IU Police Department," Lenkowsky said. "The police department had no choice it felt but to call in for bakup."

The university announced a pay hike for officers in early June, and Whitten mentioned the IUPD was receiving a budget increase in an interview on the morning the report was released.

According to IUPD, its budget allocations have increased each year for the past five financial years, from $18.1 million in 2021 to $24.1 million in 2025.

The policy recommended setting clearer expectations for when state police might be involved, but the trustees voted down one such resolution in their last meeting.

Cooley also suggested that IU “should consider adopting a policy of not issuing official statements about public matters that do not directly affect the University’s core functions.” This recommendation came after conflicting community reactions to Whitten’s statements after the Oct. 7 attacks.

That recommendation echoes SEA 202, an Indiana law passed this year limiting university representatives’ ability to speak on political and moral issues that don’t affect “the core missions of the institution and its values of free inquiry, free expression, and intellectual diversity.”

"Of course, that was enacted in May before the Cooley report was done yet," Lenkowsky said. "Not so clear the lead investigators saw that. If they did, they chose not to reference it."