(Bente Bouthier/WTIU News)

An approximately 50-mile highway corridor stretching through south central Indiana is well into its second phase of study, which started this summer.

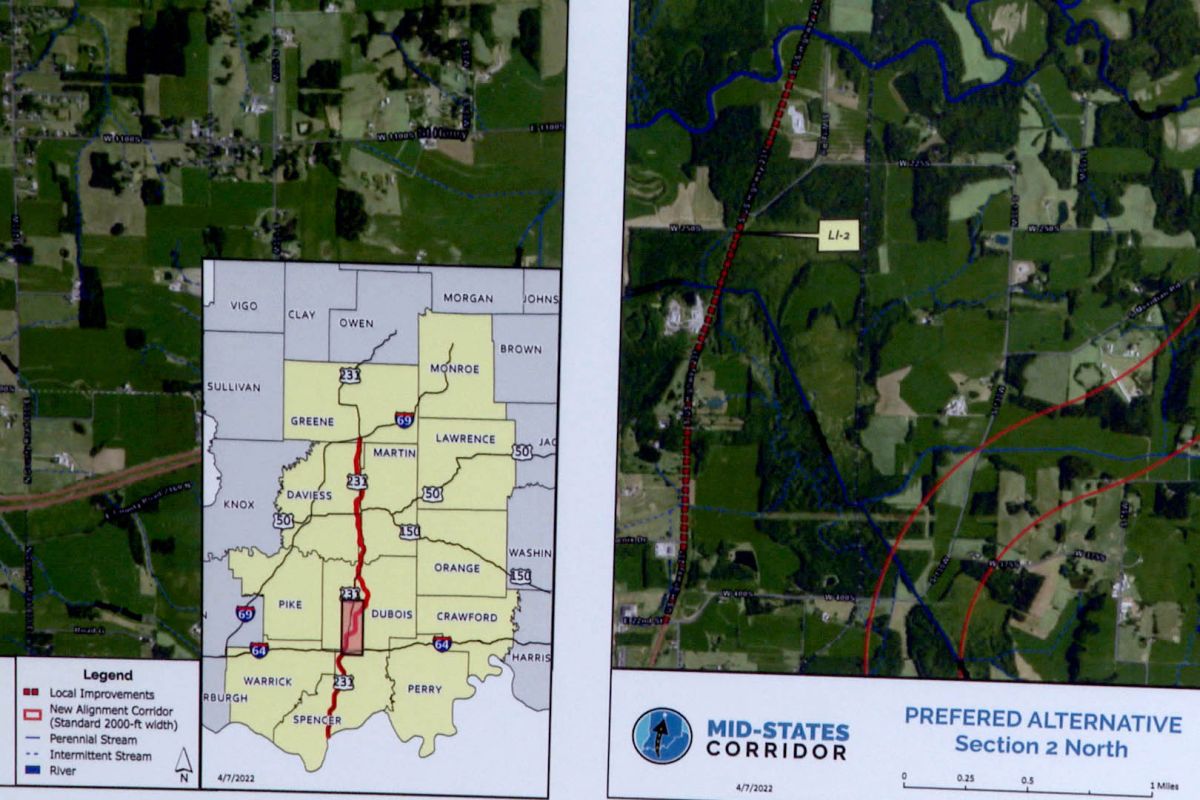

Tier One study of the Mid-States Corridor determined its 50-mile route north along Highway 231 from Spencer County to I-69 in Greene County. The route has been broken down into four chunks for more detailed analysis.

This second phase focuses on Dubois County.

Despite the forward motion, Jason McCoy, a landowner in Martin County, is optimistic that people in the corridor’s 12 county area can still block its eventual construction.

He spoke to a group at the Klubhaus in Jasper, Indiana on December 5.

“We've identified a need to come together as a group to take control of this issue. The best way to do that is to be unified,” he said.

Its planned route in Dubois County looks to bypass Huntingburg and Jasper and connect to I-69.

McCoy owns land in the corridor’s possible construction path further north. He wants residents in the area to join the newly formed Property Rights Alliance to coalesce their efforts against the highway’s planned route.

The organization is an offshoot of a group formed several years ago, ‘Stop The Mid-States Corridor.’

McCoy said The Property Rights Alliance’s creation is centered around hiring legal help. He found an attorney, Russell Sipes, to represent residents.

“…to get actual legal questions answered,” McCoy said. “And the impetus for that primarily was through the Tier One study.”

Before, land surveyors for the project were not coming on residents’ property. But now, during phase two, land surveyors hired by the state are asking for permission to come on people’s land.

He said The Property Rights Alliance needs funds to support a legal defense to demand the state follow due process before going on residents’ land.

“They want to cite Indiana code that says they have the right to come on our property,” McCoy said. “But if you read deeper into that code, there's certain parameters that you have to adhere to.”

Before Thursday’s meeting, the Property Rights Alliance had over 20 members ready to push back on land surveyors for the project going on private property. After the meeting, the group reported nearly 200 members.

The whole of the corridor is set to connect State Road 231 with I-69 in the north near the Crane Naval Base. The area being examined now is a 2,000-foot-wide path that goes east around Huntingburg and Jasper and extends to Haysville in Dubois County.

The Indiana Department of Transportation signed a contract with the Lochmueller Group in May for more than $15 million to conduct the current phase.

The Lochmueller Group is evaluating two options to skirt Jasper and Huntingburg – a two-lane road with a passing lane, called a Super 2, or an expressway– a highway with two lanes of traffic in each direction.

Nicole Minton is the Mid-States project spokesperson with the Lochmueller Group.

She said the corridor will improve connectivity and industry for the region. It’s also intended to relieve congestion on Highway 231.

A public meeting was held in September to share project progress and findings. Lochmueller created a community advisory board, comprised of business and community leaders.

Surveyors are out looking at properties, Minton said.

“Field workers who are out surveying properties, knowing what the current environment is, looking at plant and wildlife species, looking at property uses, historic properties, all of those activities are occurring right now,” she said.

Lochmueller is aware of opposition to the plan, Minton said. But people should participate so the route can reflect local needs.

“Talking about where a facility might impact their property and how they use their property,” she said. “Those sorts of conversations will be really helpful to us in making decisions.”

Dubois County is one of twelve counties to be affected by the Mid-States Corridor.

Colten Pipenger is the executive director of Dubois Strong, a group dedicated to economic development for the county.

He said Dubois County is the most populous county in Indiana without interstate access directly through it.

Between 2013 to 2019, county employment grew 7 percent, according to a local economic report. Manufacturing made up more than 38 percent of employment. The area is one of the top turkey producers in the country.

Business, farming, and manufacturing in Dubois give it a competitive advantage, Pipenger said. Logistics will play a role in keeping it.

“We have a lot of businesses here that move people and goods regularly,” he said.

The county’s largest businesses have pushed for a corridor because they are invested in the county, he said. But that doesn't mean they should have an outsized pull in infrastructure plans.

“However, there are big businesses that employ, thousands of people, whose livelihoods can be affected by this road or not having a road,” he said. “We have to take into account a little bit of that as well.”

The corridor will affect landowners, but Pipenger said it is necessary for community’s long-term survival.

McCoy disagrees. From where he’s standing, the corridor isn’t needed. He’s skeptical of potential economic benefits and said Lochmueller’s desire for public input is insincere.

Read more: Preferred path chosen for Mid-States Corridor, environmental impact study released

The federal government withdrew its 2004 and 2011 studies for the corridor in 2014. It stated, “Due to a reevaluation of the traffic information, the project is no longer warranted.”

The room was packed at the Klubhuas last month. But some attendees had concerns over the feasibility of noncompliance with land surveyors.

People may want to see the group gain traction first, McCoy said.

"In the presentation I talked about, this is what you can do, this is what you should do, and then there's what you will do," he said. "That's not really up to me to decide what you should do and what you will do. I want people to understand what they can do."

He added people can force due process to slow the study down. The Lochmueller Group will hold a public meeting early next year to present purpose and need findings.

This section of the corridor study will take three years to complete.