Sen. Tyler Johnson (R-Leo), a physician, said his experiences as a mentor to a student applying to medical school inspired a bill against diversity, equity and inclusion. (Brandon Smith)

After one student’s experience with medical school applications partially inspired Indiana Senate Bill 289, Indiana University Medical School students started speaking out in support of diversity, equity and inclusion.

SB 289 would ban DEI in the state government and public schools. The bill passed the Senate last month and headed to the House of Representatives. While the bill’s co-author Sen. Tyler Johnson (R-Leo) said discrimination in medical school caused the push to end DEI in school, doctors and students believe DEI is better for patients and education.

“It's hard because we say DEI, but we need to understand what that means,” said Olwen Menez, an IU School of Medicine student. “It's diversity, equity and inclusion, right? There is no part of this that's meant to exclude anybody. It's in the name.”

Students interviewed for this story speak on their own behalf and don’t represent the medical school.

Menez, a member of the school’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Coalition, said her identity as a woman and as an immigrant influenced her decision to become a doctor. To her, DEI means getting the best out of everybody. It means doctors have a better education and patients receive better care. But she said the proposed bill could jeopardize that.

“There's a lot in this bill that's worrying, but definitely having the government so involved in our curriculum and what we're teaching worries me a lot,” Menez said.

How med schools influenced Indiana’s anti-DEI bill

Johnson authored SB 235, which was amended and added to SB 289.

Johnson’s experiences as a doctor and as a mentor partly inspired the bill. Johnson didn’t respond to multiple interview requests, but he told the Senate in February an unnamed student mentee’s experience applying to a medical school in Indiana inspired the bill.

“He felt discriminated against, which obviously he was during this process,” Johnson said. “When you go through that process, and the process manipulated in a way that you have to assert toward an ideology that you don't agree with or you may not understand, and part of that process that's wrong.”

Johnson said the bill’s goal is to end divisive, discriminatory and manipulated ideology. Some Indiana medical faculty spoke out in support of the bill.

“I've had friends that have been asked to attest to ideology that they don't agree with, that violates their conscience,” Johnson said. “I've had medical students who are no longer at the university because they have been pushed out of medicine. How is that a good thing?”

Schools are also feeling pressure from the U.S. Department of Education, which advised cutting DEI programming, scholarships and more.

Though the bill hasn’t passed yet, the IU School of Medicine is already cancelling events such as the LGBTQ+ Health Care Conference.

Read more: IU School of Med dean says legislation caused cancellation of LGBTQ+ Health Care Conference

“We wanted to let the dust settle from this legislative session and then revisit the content and the delivery of that content,” said Mary Dankoski, School of Medicine executive associate dean for faculty affairs and professional development.

As a white student, IU Medical School second-year Wade Catt said he’s heard the idea multiple times that he’ll have to work harder than his peers. But that idea has made him uncomfortable, and he said it doesn’t represent his own experiences.

DEI doesn’t place an unfair standard on students, Catt said, but instead it’s an effort to recognize decades of promoting an almost entirely white and male cohort of physicians.

“I think that that has been borne out time and time again in the data, that this is incontrovertibly a good thing for public health,” Catt said. “We should not be promoting the opinions of a couple of very loud people who don't represent the broader medical community.”

Catt said he’s more concerned with the quality of education and politicians reaching into the curriculum.

“A politician who has no clinical experience whatsoever should not be dictating what is and what is not appropriate in medical education,” Catt said. “I think that sentiment is widespread among the student body and among practicing physicians around the state.”

Lack of diversity still in an issue in medical schools, say students and experts

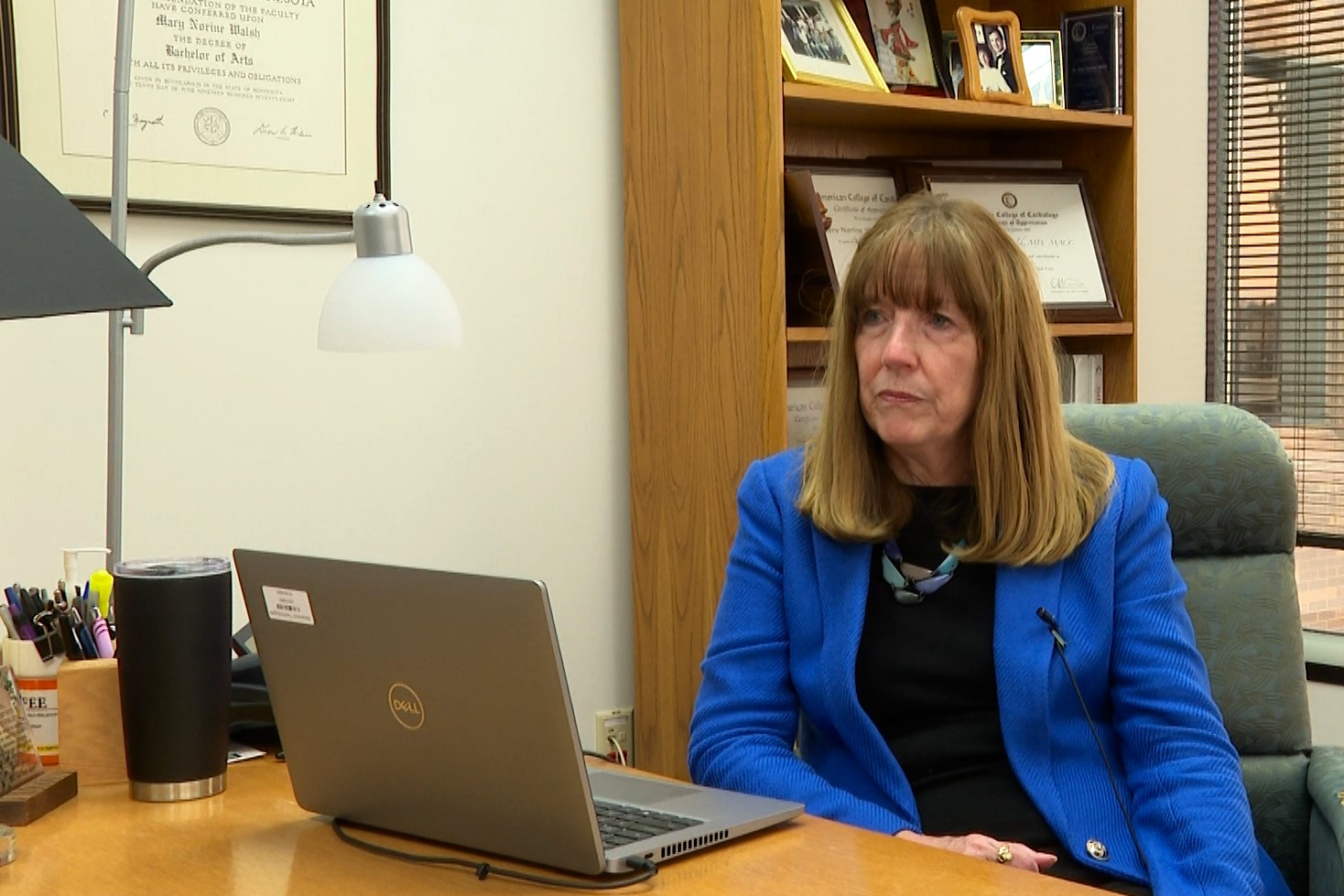

Doctors and organizations such as the Association of American Medical Colleges continue to advocate for DEI. Dr. Mary Norine Walsh, a founding board member of Good Trouble Indiana, said DEI levels the playing field and benefits patients.

Good Trouble tracks and breaks down relevant bills, and as a former president of American College of Cardiology, Walsh worked to bring more women into cardiology and focused on DEI.

“We know that patients who are seen by a diverse health care workforce — and that includes physicians, nurses and other health care people —do better,” Walsh said. “Seeing doctors and the healthcare team who look like us really matters.”

Walsh says Black, Latino and Indigenous people are underrepresented in medicine, and that hasn’t changed in years. While today more medical students are women, some specialties such as cardiology are still dominated by men.

Jasmina Davis, a first-year IU med student, is organizing with other students to speak against the bill. Davis said students still have years of training before they can practice medicine, and their biggest concern is their medical education may be overturned.

Davis said diversity is key to treating patients. Experts stress the importance of curriculum on race and equity. In order to best treat the patient, Davis said doctors should be familiar with their backgrounds.

“We're simply trying to meet patients where they are,” Davis said. “To have people that look like them, and to have people that they can confide in and understand their lived experiences is, I think, one of the most crucial things in medicine.”

After affirmative action and race-conscious admissions were banned in 2023, medical schools such as IU’s saw dramatic drops in diversity. In 2024, the Indy Star reported Black and Latino enrollment dropped from about a quarter of the incoming class to about 9 percent. Across all of Indiana, Axios reported the share of Black, first-year medical students dropped to about 5 percent.

“The vast majority of students are coming from upper-middle class, wealthy backgrounds,” Davis said. “I'm not seeing very many Latino or African-American students.”

Menez said critics of DEI should instead focus on removing financial and class barriers to medical school.

“The medical school application process was exhausting — the finances behind applying to medical schools, going to all the interviews, paying to take the MCAT many times if you don't get the score you need on the first try,” Menez said. “In my opinion, as somebody who doesn't come from a family of doctors, I think they're focusing on the wrong thing.”

Aubrey is our higher education reporter and a Report For America corps member. Contact her at aubmwrig@iu.edu or follow her on X @aubreymwright.