Skyler Wampler listens to directions at a martial arts lesson in Bloomington. (Lauren Tucker)

Editor's note: This story contains descriptions of self harm and violence, and mentions suicide.

Kids in red uniforms and different colored belts line up on a mat and started drills for their martial arts lesson in Bloomington. The instructor demonstrates self-defense moves.

“Whatever happens,” he tells the kids, “keep moving forward!”

That is what Skyler Wampler of Owen County is trying to do after what his mother said was years of bullying at Edgewood Schools, which are operated by the Richland-Bean Blossom Community School Corporation. From afar, the scar on Skyler’s head from a bully hitting him years ago wasn’t visible.

But for Skyler and others, bullying carries lasting physical and emotional damage that can impede education. It can be worse than the everyday hard knocks people, even children, must learn to endure.

That’s why he’s learning taekwondo.

“Our biggest thing is to push them away a little bit and say, ‘Get back, leave me alone,’” said Jennifer Wampler, Skyler’s mother. “And you say it loud enough that a teacher can hear you, or someone can hear you, and he's used that instead of having to be afraid.”

It’s unclear whether the alleged incidents were reported in state-mandated school bullying statistics. Experts — including lawyers, a state representative and an anti-bullying activist — told WFIU/WTIU News that the Indiana Department of Education’s system for collecting school bullying data is severely flawed. This could be due to the state’s definition of bullying.

The state has a long definition of bullying that includes “the intent to harass, ridicule, humiliate, intimidate or harm the targeted student.”

To critics, the most important point in the definition is that it has to happen more than once to be reported. A state representative tried to change that definition so that one incident could count as bullying. But the bill stalled in the Senate.

Some schools don’t even show up in the state’s statistics. Edgewood Primary School, for example, isn’t listed in the second-most-recent state statistics, from 2022-23. An official with the school corporation called it a “mechanism error.”

The Monroe County Community School Corporation’s most recent report is missing 14 schools, including both high schools. An official said if a school did not have any cases of bullying, MCCSC would not include that school in its report to the state. That means for an entire academic year, those 14 schools combined claim to have not had a single reportable case of bullying.

Attorneys Tammy Meyer and Catherine Michael, who represent severely bullied kids in lawsuits, said it’s a huge failure in the system. While working with clients across the state, they have seen a significant increase in bullying cases not only in Perry Township Schools, where they have a pending lawsuit, but also in Monroe County, Lake County and Terre Haute.

“The bullying is not being reported by the schools like they are required to do to the Indiana Department of Education,” Meyer said. “When you look at those reports, some districts are doing a good job of reporting. You might see 60, 70 bullying reports for a particular district, and then you might see a large district and it's zero. And you know that cannot possibly be true, they're just not reporting it.”

Read more: Would you want a bully's parents to pay a fine? Some anti-bullying advocates say 'Yes'

The IDOE did not respond to interview requests to explain what the reporting process looks like and to respond to complaints that their statistics don’t properly reflect the issue.

Multiple emails were sent to the IDOE and a reporter visited the office to request an interview. A person at the office said to call the communications office, and no one returned multiple calls.

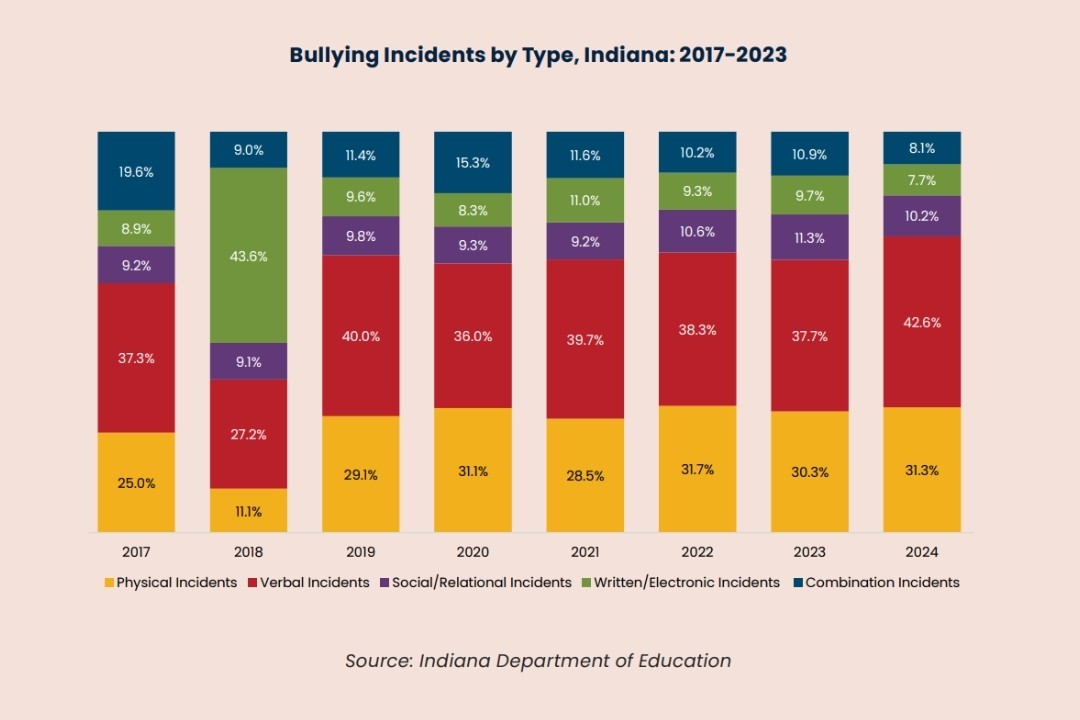

The Indiana Youth Institute reports that 40.6 percent of parents in Indiana reported their child aged 6-17 was bullied in the 2022-23 school year. This is higher than the national rate of 38.4 percent. In the last five years, verbal incidents have been reported to be the most common form of bullying, followed by physical incidents. Bullying numbers have been on the rise since 2021, with 1,984 incidents reported in 2021 and 7,700 reported in 2024. Last year had the second-highest number of bullying incidents in the past decade.

Rachel Van Alstine from Elkhart, an activist on the bullying issue, has worked with a state representative to change the state’s definition of bullying. She said that because school districts “police themselves” on reporting, bullying goes widely unreported.

“Schools are competing for staff, for funding for students, and so there's no incentive for them to be honest about what's really happening with our children and in these school environments,” she said, “and that is a scary place to be in, because what that means is that they are choosing liability over our children's safety.”

That makes it hard to understand the scope of the problem.

“There's no consequence,” she said. “And so the system itself is what is perpetuating the abuse."

Verbal abuse, self-harm — and much worse

When Mickey Anderson was 12, he broke apart the razor piece from a pencil sharpener and kept it in his phone case. He started cutting himself on his thighs — he said they could easily be covered — wherever he was alone, even the school bathroom. Eventually, bandages couldn’t cover the 20 to 30 cuts he would make at a time.

“I normally wore multiple layers so nothing ever bled through,” he said. “I just went on with my day.”

He said he was bullied at multiple schools, including Owen Valley Middle School and Edgewood High School. Officials of the Richland-Bean Blossom Community School Corporation said they can’t discuss individual bullying allegations because of student privacy laws.

He harmed himself for over four years because he was bullied. People called him names and threw rocks at his car. His family and peers weren’t accepting when he came out as a transgender male.

“I felt as if the pain was punishment I deserved,” he said, “so no meds were necessary.”

Now 23, Anderson said he is antisocial as an adult and was diagnosed with depression because of bullying.

Carly Collier thought she would graduate from Edgewood High School with the people she’d known since kindergarten. But bullying got in the way of that.

Carly said she was verbally bullied on her softball team and on social media because of her perceived limitations as an athlete, which put her on the junior varsity team instead of varsity.

Carly joined Bloomington High School North’s team when she transferred for her senior year.

“It's a big relief off my shoulders to be able to play and not feel like I'm walking on eggshells all the time,” Carly said.

Because of how much she was bullied, Carly stayed home a lot more. She didn’t want to talk with her friends or go out. When she got home from school, she would either sleep or color in her living room.

While they couldn’t speak to specific cases because of student privacy, Edgewood school officials said they empathize with parents.

“It makes me feel like I can do more,” said Jordan Key, assistant principal at Edgewood High School. “It makes me want to be better.”

A recent lawsuit against Perry Township Schools alleges a teenager, James, experienced violent bullying that wasn’t addressed by Perry Meridian High School, where he attended.

In one instance, James was attacked by other students, punched and pushed into the steel rails of a staircase. He lost consciousness, the lawsuit alleges, and there was “blood pouring uncontrollably from his face, head, and ear.”

Video surveillance cameras captured the incident. One student posted a photo of James lying on the floor with the caption “perry so ghetto” and laughing emojis.

The lawsuit alleges James suffered multiple physical injuries, and now suffers from depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

“He experiences regular flashbacks of the attack,” the lawsuit said, “and lives in constant fear of running into his attacker, being attacked by others, or being harmed.”

In a statement, officials of Perry Township Schools said they are limited in the details they can share due to student privacy laws, but assured they take bullying seriously.

“We are confident that these facts will not support the false narrative currently being shared about our Southside community and schools,” the statement said. “A Perry Township Schools police officer intervened within seconds. The suspect was taken into custody, and the victim immediately received medical care.”

Whitley County Consolidated Schools did not respond to requests for comment on a lawsuit brought by a mother whose son took his life after being bullied at Columbia City High School, near Fort Wayne.

The complaint says Collin, a special education student at Columbia City High School, experienced physical and verbal bullying: kids mocked his behavior and struggles with social communication.

The lawsuit said Collin didn’t feel safe at school. In November 2022, Collin made a post on social media criticizing the school’s failure to address bullying. Four days later, he was suspended. The bullying still went unaddressed.

The suit says Collin’s friend gave him a revolver in school on or around Feb. 3. The lawsuit alleges the school failed to prevent it from getting on school grounds, even though video footage captured multiple students with the firearm.

Later that night, Collin used the gun to commit suicide.

Trending the wrong way

Bullying is getting worse, according to state statistics.

But the state requires schools provide bullying prevention education, from kindergarten to 12th grade, by Oct. 15 of every school year. This consists of counselors, social workers and teachers giving lessons on what bullying is and how students can help peers who may be bullied.

Edgewood Schools and the Monroe County Community School Corporation report bullying cases similarly. When they hear of a potential case of bullying, they gather as much information as possible to determine whether it counts as bullying in accordance with the state’s definition. Depending on the case, they may refer the student to a counselor to help them.

Edgewood reports cases to the state through an online portal called Harmony. They report specifics of the case, results of the investigation and how it was addressed.

“Once a report is made, it has to be addressed,” Key said. “It's in there. It can't just go unresolved.”

Despite state trends demonstrating an increase in bullying, Jennifer Barrett, director of teaching and learning for Edgewood Schools, said she believes there has been a decrease in cases at Edgewood. She attributes this to a six-year effort of preventive measures, such as requiring training for all staff members to learn how to prevent bullying and hiring social workers and counselors to help kids resolve conflicts.

But Michael and Meyer have seen more parents taking their children out of school and enrolling them in online school or homeschooling to get away from bullying. They say this isn’t a sustainable way to address the issue.

“This has been going on for years, and unfortunately, what we see is that it does take a lawsuit, a civil lawsuit for monetary damages, or several civil lawsuits to get their attention and finally create some change and do something about the problem,” Meyer said.

Kylene Varner, legislative liaison for the Indiana Association of Home Educators, said she has seen more parents withdraw their kids from school to homeschool due to bullying. However, not every parent has this option to solve the bullying problem.

“It has become more typical for parents to report this kind of behavior,” Varner said.

The flexible, low-stress environment of homeschooling, Varner said, has allowed kids’ anxiety levels to decrease.

“They're [parents] having difficulty getting them to school, because the children are just anticipating that behavior coming at them,” Varner said. “And nobody wants to walk into that, right? Nobody wants to willingly walk into being mistreated. And so they bring them home, they remove that stressor, and the children feel more at ease, more relaxed.”

Skyler, who went to Edgewood, will start homeschooling this fall after switching public schools once.

“He (was) afraid he’d get bullied more,” Wampler said.

Politics, bullying and social media

Jan Desmarais-Morse, executive director of the Indiana School Counselor Association, said she thinks bullying across the state is becoming more widespread due to the political climate and toxicity of social media.

She also doesn’t think adults and leaders are doing enough to set an example to kids on how to properly treat other people.

“People are just reacting now, and they're trying to control other people,” she said. “And when you try to control other people, you yourself become out of control, right? … I think we see that on a local, state and national level at times, and so we have to do the opposite of that. If we're not showing them the way to be better, then they're not learning how to be better.”

Edgewood officials say they’ve seen bullying occur on social media through posting mean comments and taking photos on Snapchat without permission. In Perry Township Schools, Meyer sees kids filming and posting bullying incidents.

“They're filming it in the hallways, in the bathrooms, in the gym, and then they're posting about it on all sorts of social media platforms, and they're bragging about what they're doing, and they're just blatant about it,” Meyer said. “And I think the increase in social media has attributed some of that to what we're seeing now.”

Rep. Vernon Smith (D-Gary) had a bill, “Education matters,” that passed unanimously in the House. It would have expanded the definition of bullying that has to be reported. A single incident could prompt reporting. The bill stalled in the Senate.

Read more: Window to notify parents of school bullying could tighten under Indiana House bill

Smith said he doesn’t believe the state’s Department of Education is emphasizing the issue enough.

“I know that the Department of Education has a lot of responsibilities, but what you prioritize means that you're going to give more attention to it,” Smith said. “And if you see it's a need, then you go and you meet that need. There is a need in this state.”

Edgewood officials think changing the definition so that one act of aggression counts as bullying could “unnecessarily” inflate the data. To them, it’s unclear whether there is an underreporting problem.

“At the end of the day, I don't know that the reporting piece of it is something that is most important,” said Matt Irwin, assistant superintendent for Edgewood Schools. “I think the most important thing is the education that we're putting into our kids' hands and into their minds to help them to be better citizens, to be better friends, to be better learners.”

‘Don’t make me go back’

Even Edgewood’s efforts to educate kids on bullying didn’t prevent Skyler from being bullied.

When Skyler attended Edgewood Primary and Intermediate Schools, he was a target of bullies because of his autism. Kids would trip him, call him names and hit him with toys and fists on his head. He was straddled and punched on the school bus.

“He would be coming home begging and crying, ‘Mommy, don't send me back to school. Don't make me go back because it hurts,’” Wampler said. “And that would just make me cry every time because you have to send them, and I didn't want to send them back there. And it still breaks my heart just thinking about it and seeing a child have to go through that.”

Despite assurances from school leaders, parents still say they feel helpless when trying to support their kids through the bullying.

“Am I letting him down?” Wampler said she asked herself. “And am I a bad mom?”

Parents in this story, including Carly’s mom, Betty, said they didn’t know whether the bullying their kids faced was reported to the state. They think educators need to take bullying more seriously.

At the end of the interview, Betty had a plea for them:

“Do more for our kids.”