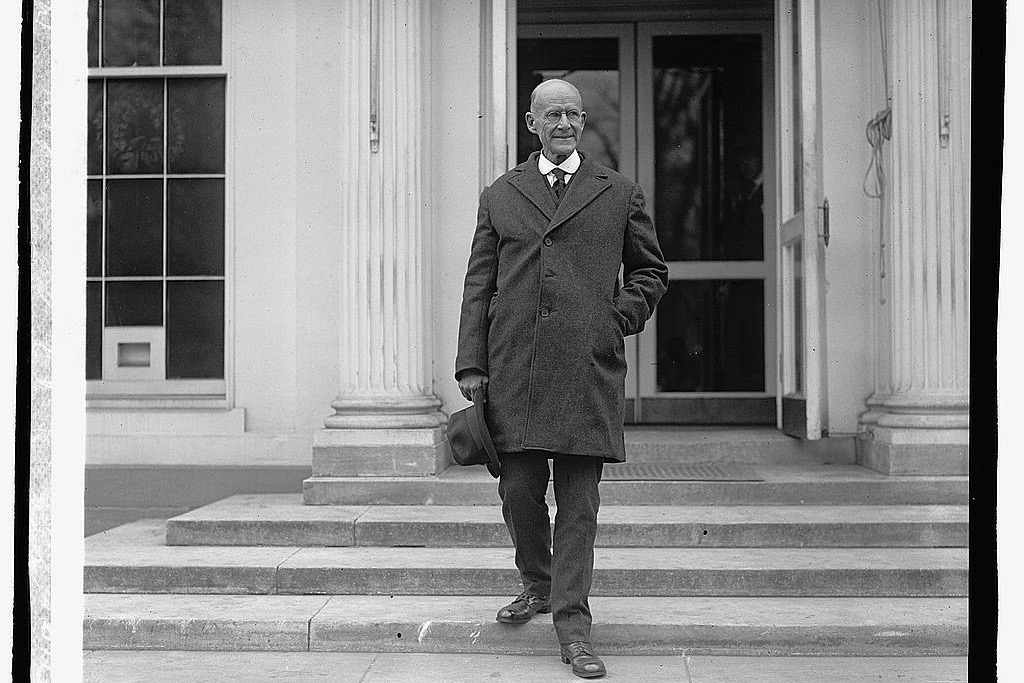

Eugene Debs leaves the White House, December 26, 1921 - three days after President Warren G. Harding commuted his prison sentence. Debs was jailed for violating the Espionage Act after delivering an anti-war speech in Canton, Ohio in 1918. (Library of Congress)

Born in Terre Haute in 1855, Eugene Debs was a labor leader, activist and politician perhaps best remembered for his five consecutive runs for president as the candidate for the Socialist Party of America between 1900 and 1920. Debs was instrumental in the labor and unionization movements of the late 19th Century after he served one term as a Democratic state senator in the Indiana General Assembly.

He also was a key force behind the creation of Labor Day as a federal holiday when the American Railway Union, of which Debs was in charge, backed striking Pullman Palace Car Company workers by boycotting trains that used Pullman cars, leading to the nationwide Pullman Strike in 1894.

The Eugene V. Debs Museum is located on the Indiana State University campus in Terre Haute.

Reporter Mitch Legan spoke with IU history professor Carl Weinberg about Debs’ influence on Labor Day and current American politics.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and conciseness.

Mitch Legan: You're the historian, so you can say if I’m correct or not, but from what I've read, [Debs] was pretty integral to the creation of Labor Day as a U.S. holiday. The American Railway Union backing the Pullman Strike kind of pushed [President] Grover Cleveland to [make] Labor Day a federal holiday. Would you say that is accurate? And if so, could you explain how Eugene Debs was instrumental in that?

Carl Weinberg: I do think it is accurate. Pullman was this odd little city completely surrounded by the City of Chicago at the time. And [it was] run as a company town by George Pullman, the owner of [the Pullman Palace Car] Company that made these luxury “Pullman palace cars” at that time, which was the ultimate way to travel in the 1890s. And in the early 1890s, there was an economic depression and it was putting great pressure on companies to lower their costs.

Eventually, [Pullman] did cut [workers’] wages pretty substantially and yet, still charged them the same for rent as they had been paying. And so these workers felt awfully squeezed and eventually went out on strike [in May 1894].

Debs was initially reluctant about calling workers out in support of Pullman strikers. To organize a sympathy strike or secondary strike was considered somewhat radical because he was asking people who were not themselves suffering directly from the effects of George Pullman's actions to sacrifice in support of a greater cause. But he was convinced to go along with it, and it became this massive labor action through much of the country in support of the Pullman strikers.

[President Grover Cleveland eventually sent federal troops to Chicago to quash the strike and stop it from affecting U.S. mail] and things got pretty intense, especially in Chicago, where troops came in and workers were fired on. They retaliated in kind, especially destroying railroad property.

Cleveland was aware that he was hated by many workers around the country for having sent in federal troops to Chicago and [having] issued a federal injunction to arrest Eugene Debs and other leaders of the American Railway Union. And so he was clearly looking to boost his popularity a bit by trying to demonstrate that he, in fact, was the friend of workers.

The momentum built up over time and eventually, in [June] 1894, Grover Cleveland did sign this law, making it a national holiday – at that point applying only to federal employees. So average workers didn't necessarily get a paid holiday.

ML: [Debs] gets thrown in jail for what they said was obstructing U.S. mail, and from what I have read, he comes out of jail as kind of a full-fledged socialist. Is that accurate and what was he pushing for?

CW: I think it's a little bit of a myth that he went into this federal prison in Woodstock, Illinois, with no notion of socialism and magically came out a full-fledged socialist. It does seem that he was campaigning in 1896 – the year after he came out [of prison] – for William Jennings Bryan, who was the Democratic candidate.

Later as a socialist, he rejected the two-party system and said that workers had to pursue their own political alternative of their own party. So he was, I think, still in transition in his views. But as you say, he and others founded a number of organizations: Social Democracy, the Social Democratic Party and eventually the Socialist Party of America in 1901. And these organizations were coalitions of a whole broad range of people, including union workers, who wanted fundamental change. They had decided that the profit system was at the root of their troubles. And they wanted to live in what Debs called a “cooperative commonwealth.”

In 1912, when Debs got about 900,000 votes nationally in the presidential election, about 36,000 people in Indiana voted for him. And there were branches of the Socialist Party at that time in a lot of major towns throughout Indiana: Marion, Kokomo, Indianapolis, Evansville, other places like that. So Debs was clearly popular in Indiana – in a state that's often considered a conservative state. I think that says a lot about that era and about Debs, that he was able to command that kind of support in the Hoosier State.

ML: [Debs] obviously influenced the Socialist Movement. And now, in our current political climate, we are seeing a bit of a revivification of socialism. [Vermont Senator] Bernie Sanders has run two campaigns and he's had decent support for both of them. He’s a huge fan of Eugene Debs. How has Debs impacted the current socialist revitalization?

CW: [Early in his career Sanders] really seemed to identify with Debs’ revolutionary message and this idea that working people had to reject both major political parties. But Sanders since then has very much become part of the establishment, even if he's not registered as a Democrat.

He's certainly not talking about revolution, in the sense that he was talking about it in 1979 [when he was championing the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua]. And I think that if you compare what Debs was saying, the radical nature of his message in 1918, when he was arrested for speaking the truth about World War I in Canton, Ohio, I think that Sanders is quite different, a far milder version of socialism.

During that famous speech that led to his [second] imprisonment – when he ran for president in 1920 – [Debs] paid tribute to the Bolsheviks in Russia; that they had taken power, that they had pulled Russia out of the war; that they were a beacon of light to the oppressed peoples of the world. And Sanders has nothing to say about that part of the revolutionary tradition. So I think even though he's clearly influenced by Debs, I think he's a far cry from Eugene Debs.