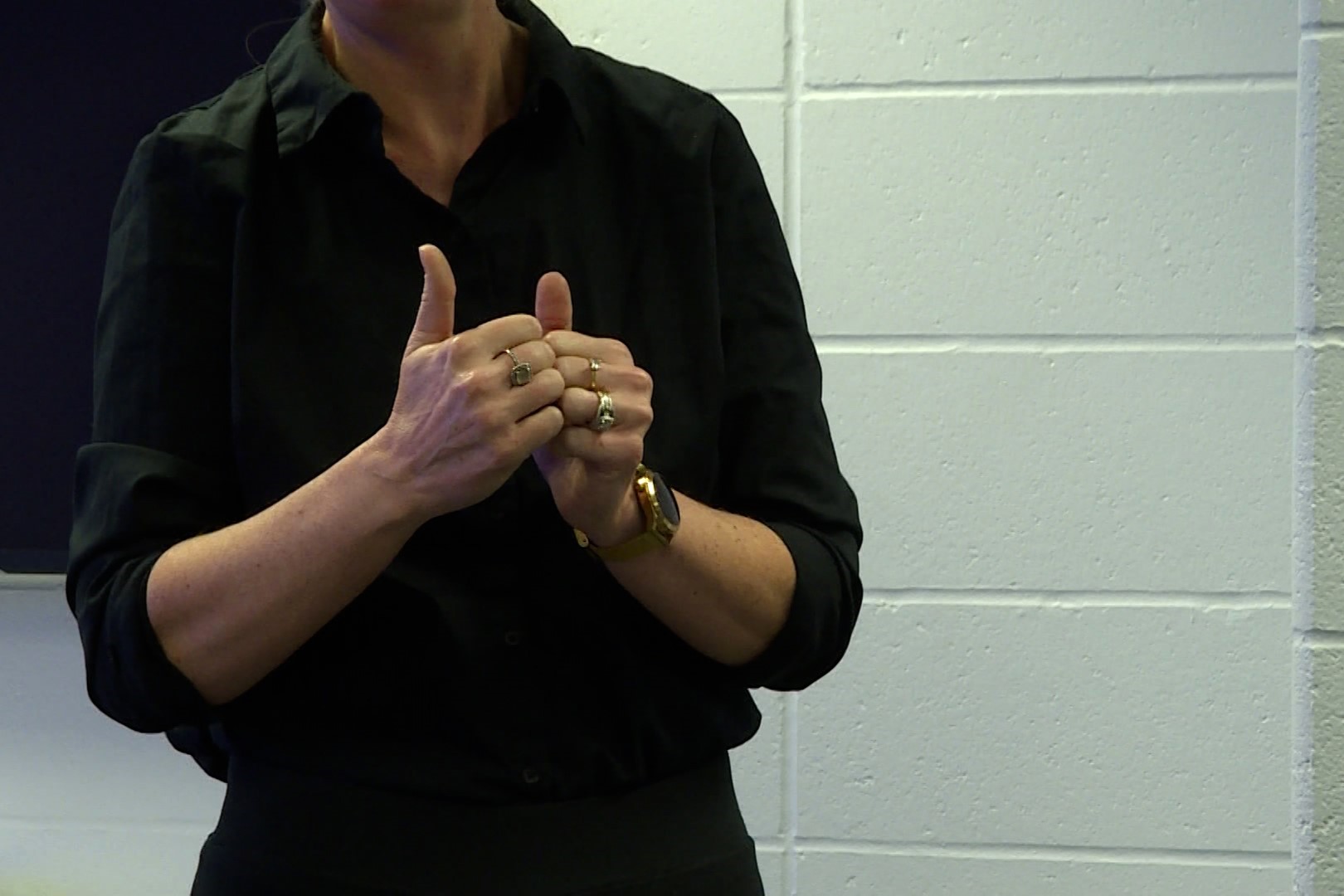

Indiana University senior Paige Moore completed three internships with the Gregory S. Fehribach Center. Last summer she worked with dietitians at Eskenazi Health. (Chris Meyer / Indiana University)

It’s been years since Paige Moore started looking into college internships. As a freshman at Indiana University, there weren't many options.

First, paid internships were hard to find. And then she had to find somewhere that helps people with disabilities. Moore is hard of hearing, and she uses a sign language interpreter. She felt like she was at a disadvantage.

Then she found the Gregory S. Fehribach Center at Eskenazi Health.

“It felt like the perfect match,” Moore said.

Now a senior, she has three internships under her belt, all helping build up the neuroscience major’s resume.

Moore is one of 195 college students with physical disabilities who have been matched with internships thanks to the Fehribach Center, Director Larry Markle said. Those students have participated in about 400 internships in and around Indianapolis.

Markle said the program usually accepts about 65 students from Indiana and surrounding states each summer.

“The purpose behind the Fehribach Center's internship program is to make sure really highly talented, qualified college students with physical disabilities get access to quality internships, so that they can have experiences on their resumes that make them good candidates for employment after graduation,” Markle said.

Fehribach Center’s internship program began with just one student

The U.S. Department of Labor reported about 37 percent of people aged 16-64 with disabilities were employed in October. For people without disabilities, that figure went up to 75 percent. Unemployment rates for youths with disabilities were also higher.

Almost one in five college students report they have a disability, and college graduates with disabilities usually struggle more to find jobs. Most barriers are because of attitudes towards people with disabilities, Fehribach Program Manager Carlos Taylor said.

“There's a perception that exists, in general, that individuals with disabilities aren't fully capable of performing or being responsible for job-related tasks and in a workplace environment,” he said.

Watch: How climate change impacts people with disabilities

The internship program's roots are at Ball State University. The center’s namesake, lawyer Gregory Fehribach, is an alum and former Board of Trustees member. The idea for the center began as a question from Fehribach. At the time, Markle was director of Disability Services at Ball State.

“How come I never see people with disabilities in leadership positions and on boards? And what can we do about it?” Markle said. “So we realized that our students with disabilities at Ball State weren't as engaged in the career development process as they should be. And so using Greg's connections we started a little internship program with one student a decade ago in 2013.”

A Ball State student who uses a wheelchair became the first participant of what would become the Fehribach Center’s internship program. The student worked at Eskenazi Health, Markle said, and then the hospital asked for more interns.

The program has expanded to 36 colleges, and it found a new home in Eskenazi Health, Markle said. Thirty-nine employers — including Eli Lilly, the Indiana Pacers and the Indianapolis Children’s Museum — have taken on interns.

Markle and Taylor now help lead the program and place students with physical disabilities in full-time paid Indianapolis internships. Markle said students are matched with employers after a screening interview based on their major and goals, and they have final say in where they intern. The process is meant to be personalized, he said.

Read more: Why this Indiana family keeps going back to a school they say fails their son

Taylor said people tend to think just going to college is a “magic ticket” for lifelong employment, but college students with physical disabilities have to think of other ways to stay competitive in the workforce. Experience and internships are ways to do that, he said, but they're usually an afterthought.

“And then it's really difficult for them to compete in the workforce when they don't have the work experiences that their non-disabled peers have on their resume,” Taylor said.

Sorting out barriers interns with disabilities may face

Taylor said the center works with employers to accommodate interns. Students may have disabilities relating to sight, hearing, mobility or orthopedics.

Some students can’t drive, so they’re provided free transportation from Eskenazi Health or Uber vouchers. The center also sorts out workplace accommodations. Students have access to screen enlargement software, screen reading software, large screen monitors, voice-to-text dictation software, live captioning and American Sign Language interpreting.

“We hope to foster an environment for college students with physical disabilities where the disability is not the primary focus,” Taylor said. “Gaining the work experience, the skills that are necessary that's going to make them more competitive as they enter the workforce is the main focus.”

Moore said because Taylor and Markle sort out accommodations with employers, she doesn’t have to worry about when to disclose her disability or how to schedule an interpreter.

Watch: Advocates concerned about wages of workers with disabilities

One of Moore’s favorite parts of the internship is living at IUPUI’s Riverwalk apartments. Interns stay there for free, and she met other interns with disabilities. She said she found a community of people who are “at a disadvantage in the normal world.”

“We also shared a similar struggle going out in the world, but we were all kind of united in that,” Moore said. “We're able to connect more because of that. Not only do we have this disadvantage, or this disability, but we're able to overcome that and strive to be better people.”

Moore’s three internships were different.

Moore worked at Eskenazi Health first, shadowing doctors who worked with dementia and Alzheimer patients. At the time, she was interested in clinical neuroscience. After the internship, she decided to pivot.

Her second internship, with IU Methodist’s neuroscience research department, she collected data to study brain degeneration in dementia and Alzheimer patients. This time, she knew she was “definitely interested in research.”

Her third internship covered diet and the brain, she said. Moore asked to work in that field, and Markle and Taylor made it happen.

“All the other opportunities were amazing, but this one was my favorite because I got to work and I learned so much about nutrition, and what a typical dietitian does,” she said. “I felt like that really helped me get that foundation that I need for my career, because I definitely want to do research in neuroscience and the implications that diet and nutrition can have for cognitive and degenerative disorders.”

Read more: People with disabilities don’t have enough dental care facilities. IU is constructing a new clinic

Each week in the summer program, guest speakers lead professional development workshops and disability advocacy in the workplace, Taylor said.

People with disabilities have a lot of fear when trying to find work, Taylor said. If an employer finds out they have a disability during the job search, they may not get an offer. He said students will have to be more proactive to get accomodations in professional settings.

“We want to talk about those scenarios and help them think ahead of time how they want to approach those situations individually, because it's different for each person,” Taylor said. “We want to help them think about that ahead of time so that they aren't scrambling and trying to figure out what do I do next? How do I do this? What should I say?”

‘Life changing’ career experience for college students

Markle said about 93 percent of interns engage in career development after the internship, meaning some graduate and find employment or continue with undergraduate and graduate degrees.

"We're seeing a high rate of students with physical disabilities who participated in the program find equitable employment after their internship," he said.

IU Bloomington and IUPUI sent 16 interns last summer, according to the annual report. IU Bloomington hosts Markle, Taylor and other Fehribach leaders each fall and summer to introduce students to the internship program.

Listen: WFIU's podcast Rush to Kill

Rachel Gerber, associate director for university relations at the Career Development Center, said the relationship began when the Fehribach Center reached out to IU to learn if any students fit into their internship program.

The relationship has grown, and IU students completed 90 internships over the years, according to Markle. Each year, there’s a “great response,” Gerber said.

“We all know, experience is the number one thing that helps students and anybody to get those post-graduation opportunities,” Gerber said. “I would say that for the students, the opportunities with the Fehribach Center are, quite frankly, life changing.”

Students who want help are not required to disclose their disability, Gerber said, and career coaches will help anyone working toward success after college.

Gerber’s office works alongside Accessible Educational Services to prepare students with disabilities for careers and jobs like the Fehribach internships.

They’ve helped students find their strengths and connected them with accessible opportunities, she said. Getting the word out about disability programs can be tough because no one is required to report their disability to the university. IU Bloomington promotes the program over email to all students.

In January, just before applications are due, Gerber makes sure students are prepared. Students need an updated resume, cover letter and three letters of reference to apply.

Watch: WFIU & WTIU News on YouTube

“I also have opportunities for students to drop in for resume review, as well as to help them with their application, their cover letters, in order to be able to apply for that Jan. 31 deadline,” Gerber said. “So that's been a really, really great opportunity for me personally to support the students and to make those connections.”

Gerber said career coaching is all about pointing students toward success after their time at IU is up, and intentional resources and relationships help students move forward.

“I think that's what we all hope for because they're such fantastic students, and we want to see them thrive and find fantastic opportunities when they graduate,” Gerber said.

What is Moore going to do after graduation? That’s the “big, scary question,” she said, but right now she has an answer. She said she’s planning on working and getting more hands-on experience before going to graduate school. She wants to work in research with neuroscience and nutrition, a combination she studied in her third internship.

She has lots of experience added in her resume, but she has concerns, like knowing when to tell her employers she’s hard of hearing or if she should ask for an interpreter.

“There is concern with that, but I feel like the Fehribach Program has given me the tools to work through that and to navigate that job search,” she said.

Aubrey is our higher education reporter and a Report For America corps member. Contact her at aubmwrig@iu.edu or follow her on Twitter at @aubreymwright.