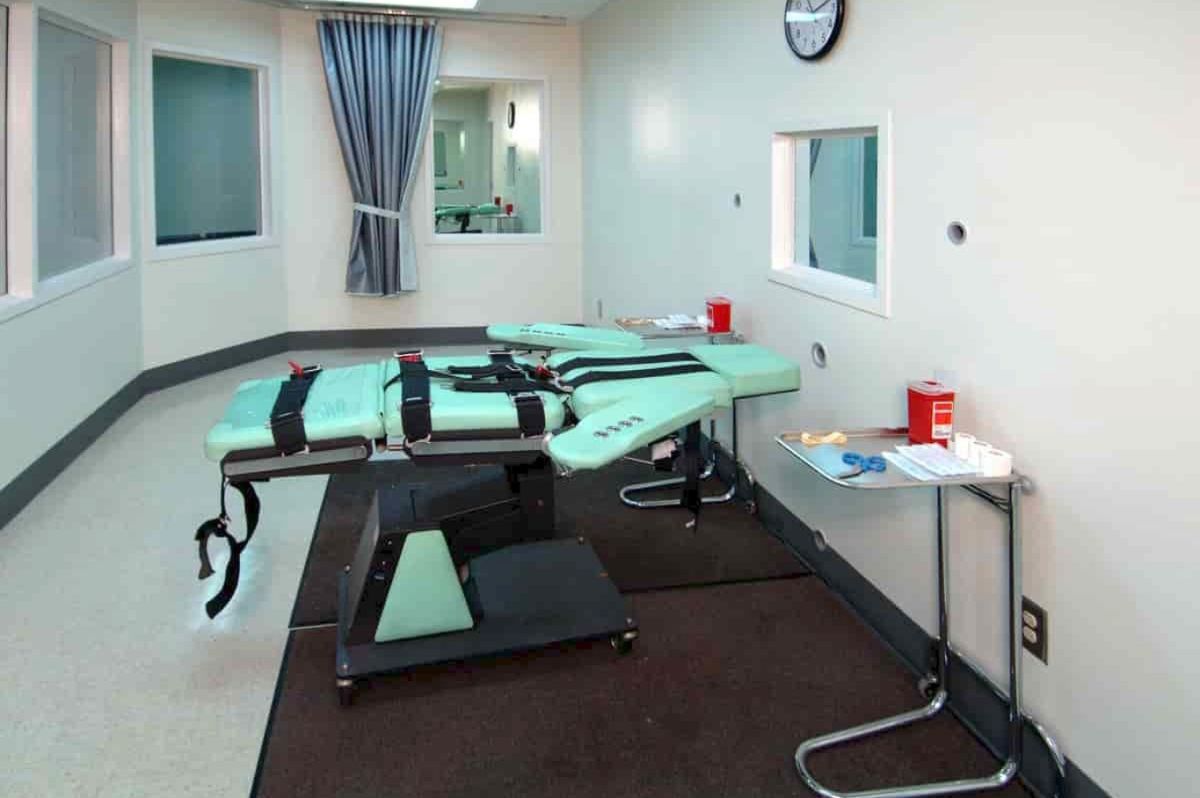

In September, the Justice Department issued a public notice seeking comment about changes to Trump protocols, including one permitting execution methods other than lethal injection. (California Department of Corrections)

In Boston, the Justice Department is pressing judges to uphold Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s death sentence. In New York, it’s asking jurors to impose the death penalty on a man who killed eight people in an attack on a bicycle path.

President Joe Biden campaigned on a pledge to work toward abolishing federal capital punishment but has taken no major steps to that end. The Justice Department continues to press for the death penalty in certain cases, even though it has imposed a moratorium that means no federal executions are likely to happen anytime soon.

Read more: U.S. won’t seek death penalty for alleged Texas Walmart gunman

In a Tuesday filing, federal prosecutors said they won’t seek it for Patrick Crusius, a 24-year-old accused of fatally shooting nearly two dozen people in a racist attack at a West Texas Walmart in 2019.

Advocates for abolishing capital punishment say mixed signals from the administration and silence from Biden — the first president to have openly opposed the death penalty -- drives home that the Democrat has not made good on his campaign promises that so raised their hopes.

Others say his inaction makes it likely a future president will resume federal executions, as President Donald Trump did in 2020 after a 17-year hiatus. With 13 executions at a prison death chamber in Terre Haute, Indiana, during his last six months in office, Trump oversaw more federal executions than any president in more than 120 years.

“The Biden administration appears to have no understanding that inaction, if it continues, will result in executions,” said Robert Dunham, who heads the nonpartisan Death Penalty Information Center in Washington, D.C. “The Biden administration executions will be carried out by a future administration. But they will be Biden executions.”

A White House email on Wednesday said the president “has long talked about his concerns about how the death penalty is applied and whether it is consistent with the values fundamental to our sense of justice and fairness,” and he supports the attorney general’s decision to impose the moratorium.

“The DOJ makes decisions about prosecutions independently. It would be inappropriate for us to weigh in on specific cases underway, but we believe it’s important for victims, survivors, and their families to get justice,” it said.

Here’s a look at the federal death penalty under Biden’s administration:

WHAT ABOUT ONGOING DEATH PENALTY CASES?

Under Merrick Garland, the Justice Department hasn’t sought the death penalty in any new cases. It also has withdrawn requests for capital punishment sought by prior administrations against more than two dozen defendants.

But U.S. prosecutors this month opened a capital trial in New York against Sayfullo Saipov, who is accused of using a truck in 2017 to mow down pedestrians and cyclists on a bike path by the Hudson River. The decision to seek death came under Trump but Garland allowed his prosecutors to continue to seek it.

Justice Department lawyers also are seeking to maintain the death sentence imposed on Tsarnaev for the 2013 bombing that killed three people near the Boston Marathon finish line. Tsarnaev is making a renewed push to avoid execution after the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated his death sentence last year.

Dunham praised Biden’s White House for not wanting to interfere in the Justice Department’s day-to-day decision making, but argued there’s nothing improper about the White House establishing an overall policy on executions.

“What they seem not to understand is that if you are setting a policy, that is not interference,” Dunham said last week. “That is setting a principle by which decisions are made. … They have failed altogether to set policy guides on the death penalty.”

WHAT MEASURES HAS BIDEN TAKEN?

Despite his campaign pledge, Biden himself has not issued any formal directives or policy statements on federal capital punishment. During the campaign, he also vowed to work at ending the death penalty in all states. He has been silent on that, too.

The most notable step by his administration was Garland’s 2021 announced halt on federal executions that had been restarted by Biden’s Republican predecessor. The Department of Justice won’t issue orders to execute anyone, at least while the moratorium is in place.

But it doesn’t stop the department from pursuing the death penalty. And it doesn’t stop U.S. prosecutors from continuing to fight legal action by death row inmates trying to avoid execution.

Read more: Lawsuit challenges isolation conditions on federal death row

The Garland moratorium is similar to one ordered in 2014 by President Barack Obama following a botched state execution in Oklahoma. Capital punishment opponents say the fact that Obama didn’t take more far-reaching action on the federal executions left the door open for Trump to restart them.

Trump officials argued that carrying out the executions was a matter of complying with U.S. law and bringing long delayed justice to victims’ relatives.

WHAT DOES THE REVIEW DURING THE MORATORIUM ENTAIL?

The Justice Department hasn’t offered details, including end goals or timetables. When asked how long the moratorium may last, Department spokesperson Joshua Stueve said in an email only that the review is ongoing.

Garland has said the review would look at protocols put in place by Trump’s attorney general, William Barr. Attorneys for death row inmates criticized the protocols, saying they allowed for hurried executions.

What the review does not entail is an assessment of whether the federal death penalty should be scrapped entirely.

In September, the Justice Department issued a public notice seeking comment about changes to Trump protocols, including one permitting execution methods other than lethal injection, such as firing squads.

HAVE ANY TRUMP-ERA PROTOCOLS BEEN RESCINDED?

No, though they serve no practical function as long as the moratorium remains in place.

In a recent letter, Democratic U.S. Rep. Ayanna Pressley and Sen. Dick Durbin urged the Justice Department to quickly annul all the Trump protocols, including one authorizing the use of state facilities and staff in federal executions, calling the orders “irreparably tainted.”

Another authorizes the use of a single drug, pentobarbital, to replace a three-drug cocktail deployed in the 2000s — the last time federal executions were carried out prior to Trump.

A replacement was needed after pharmaceutical companies began prohibiting executioners from using their drugs, saying they were meant to save lives, not take them. The Barr Justice Department chose pentobarbital despite some evidence that pentobarbital causes pulmonary edema, a painful sensation akin to drowning as fluid rushes into the lungs.

Most critics of the death penalty responded to the moratorium and review with, at best, faint praise — calling it a first step.

Dunham also noted the focus on protocols has limited impact, including because any changes can easily be undone by a future administration.

As they stand, he said, “the Biden reforms aren’t worth much more than the paper they are written on.”

WHAT DO DEATH PENALTY OPPONENTS WANT DONE?

They say Biden should draw on his presidential powers to commute all federal death sentences to life in prison, which would prevent those death sentences from ever being restored.

There’s also proposed legislation to strike the death penalty from U.S. statutes and resentence the more than 40 inmates still on federal death row to life. Biden has given no indication he supports any such measures.

The issue is a sensitive one for Biden. In 1994, then-Sen. Biden shepherded legislation through Congress that added 60 additional crimes for which someone could be executed. Some inmates executed under Trump were sentenced under those provisions.

Eliminating federal capital punishment would mean sparing the lives of killers such as Dylann Roof, the white supremacist who in 2015 shot dead nine Black members of a South Carolina church during a Bible study. Biden could find justifying that politically uncomfortable.

Capital punishment has been a hot-button issue politically in the past but is less so now after support for capital punishment has fallen in recent decades. Backing for it currently hovers around 50%, according to most polls.