Indiana's top Emergency Medical Service administrator says the system is at risk of collapse. (Lauren Tucker, WTIU)

It was almost midnight, and Indiana football fans were celebrating the team’s win over Michigan. A car driving almost 40 miles per hour struck four women, all IU students, at the busy intersection of Eagleson and 17th Street. At least two went airborne.

The first officer on the scene told dispatch: “We have one with heavy head trauma, one borderline unconscious and one critical.”

Monroe County’s main ambulance service, IU Health LifeLine, had four active trucks, but all were busy. Monroe Fire Protection District sent a unit for backup, but two of the women still needed care. Dispatch called neighboring counties, but only Brown County had an ambulance free — 20 minutes away.

Before the Brown County truck arrived, two LifeLine ambulances finished their runs and made it to the scene. The system held, but it was close.

In Monroe County it’s still hypothetical, but in other parts of Indiana it’s a major concern: what if you called an ambulance and it took more than an hour to arrive?

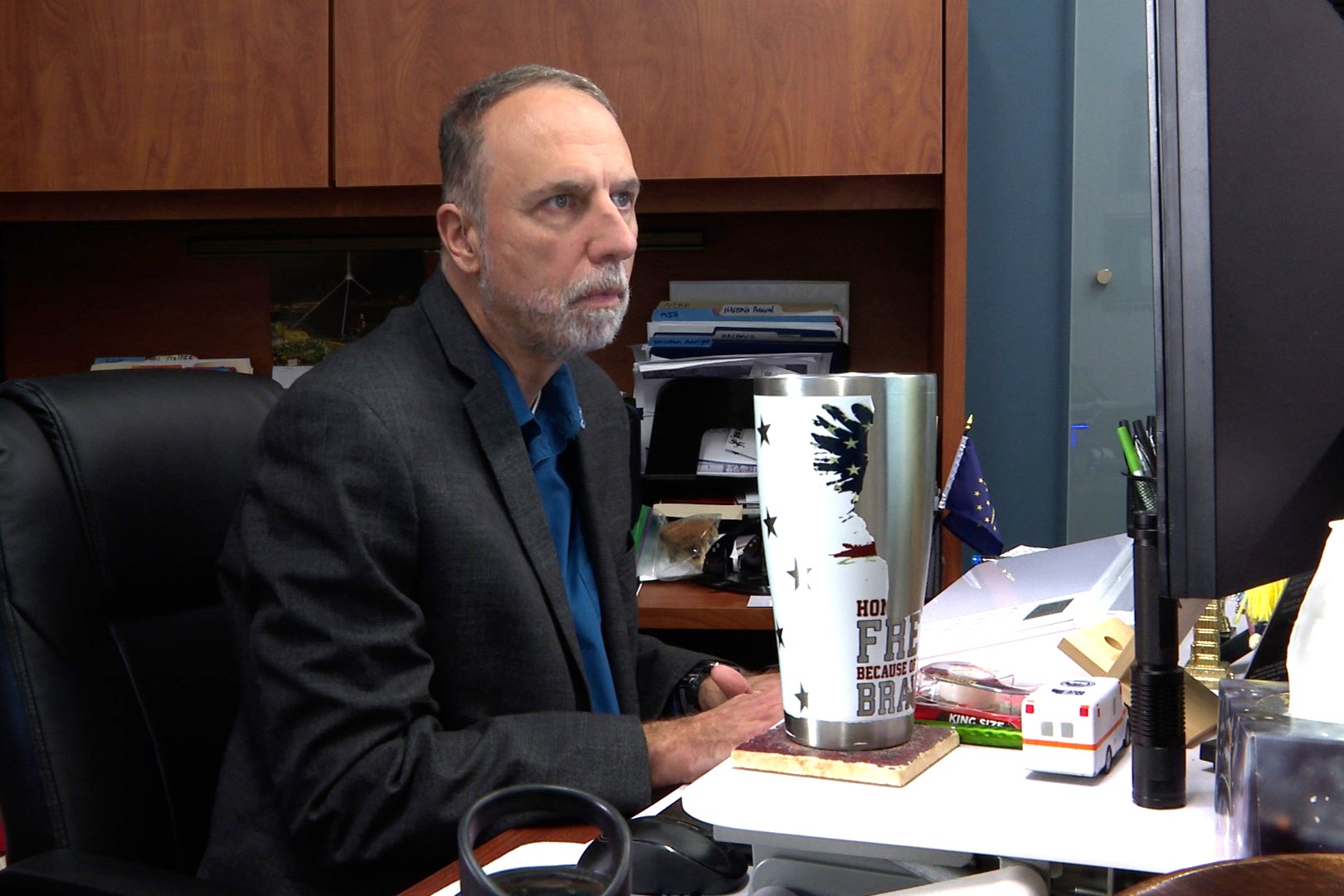

Indiana’s State Emergency Medical Service (EMS) Director Kraig Kinney said he’s beginning to see those situations more often.

“We frankly have seen a couple of counties in Indiana where the local system failed with just a few days’ notice,” Kinney said, referring to an ambulance service pulling out of a county.

Once an emergency medical technician (EMT), Kinney tracks Indiana’s ambulance service for the state Department of Homeland Security. Last year, his office reported on some of the significant problems affecting providers.

“EMS is at a crossroads,” it begins. “Run volume has increased substantially. The shortage of active clinicians does not meet demand. Funding does not meet the needs.”

Kinney told me a crisis has been brewing for decades.

“We are at a point where we either need to fix EMS or we do risk the system collapsing,” he said.

High costs, low pay

It’s not just an Indiana problem. EMS services are struggling nationwide.

Most EMS workers say the gathering storm can’t be attributed to a single cause or bad actor. Staffing shortages plague the healthcare industry, and despite attempts by lawmakers, Indiana still hovers below average on many public health metrics.

Constrained resources exacerbate the situation. EMS providers can be easily overwhelmed because emergency response is almost always unprofitable. Many patients are uninsured or unable to cover an ambulance bill.

But expenses aren’t limited by the number of runs.

“There's a cost to readiness because you aren't always using every ambulance, and you're paying them to be on duty at any given time,” Kinney said.

Some organizations limit positions and salaries to stay solvent. Many EMTs and paramedics leave their jobs for higher-paying departments or exit the field entirely, and a state survey from 2023 shows low pay is their top concern.

Read more: State officials aim to tackle shortage of EMTs and paramedics through training grants

Compensation can vary greatly between rural and urban or private and public employers, but the median pay for an EMT in Indiana is $18.11 per hour, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s just below the living wage for a single adult in Monroe County.

Emergency care is already physically demanding, and lower pay plus staffing issues put additional pressure on ambulance crews.

David Smith, a paramedic at Morgan County EMS who left IU Health LifeLine in Monroe County in 2018, said those factors led him to seek work elsewhere.

“I left IU Health because I both got sick and I got burnt out,” he said. “I mean, the average EMS career is, what, two and a half years? I certainly understand why somewhere like that people burn out quickly.”

IU Health declined a request for an interview and did not share the salary range for its EMTs or comment on current staffing levels. Spokesperson Sophie Wolanin wrote in a statement: “IU Health LifeLine assesses needs regularly and adapts staffing levels accordingly to ensure all are staffed adequately.”

The organization says online that it provides competitive pay and benefits.

While Monroe County LifeLine has six ambulances, they’re not always fully crewed, multiple paramedics and EMTs told WFIU/WTIU News. At night that number goes down to four and depending on the availability of higher-trained paramedics, some of those might only be equipped for Basic Life Support (BLS) rather than Advanced Life Support (ALS).

“The issue in Monroe County would be there’s one available ambulance in the county and there’s two runs. You got to kind of figure it out,” Smith said. “It certainly was a system that was frequently challenged to have enough resources to meet the demand.”

Filling the gaps

About the only way for ambulance services to make money is transfers, shuffling patients between hospitals and nursing homes. These patients are almost always insured.

LifeLine started as a transfer service in 1979 and began offering EMS in 2015. It still runs transfers throughout the state. That’s important, but it diverts resources from emergency response. A facility transfer can take up to an hour or more depending on distance.

“If someone needs to go from IU Health Bloomington to Methodist for treatment, the same ambulances that do 911 will be doing the transfers,” Smith said.

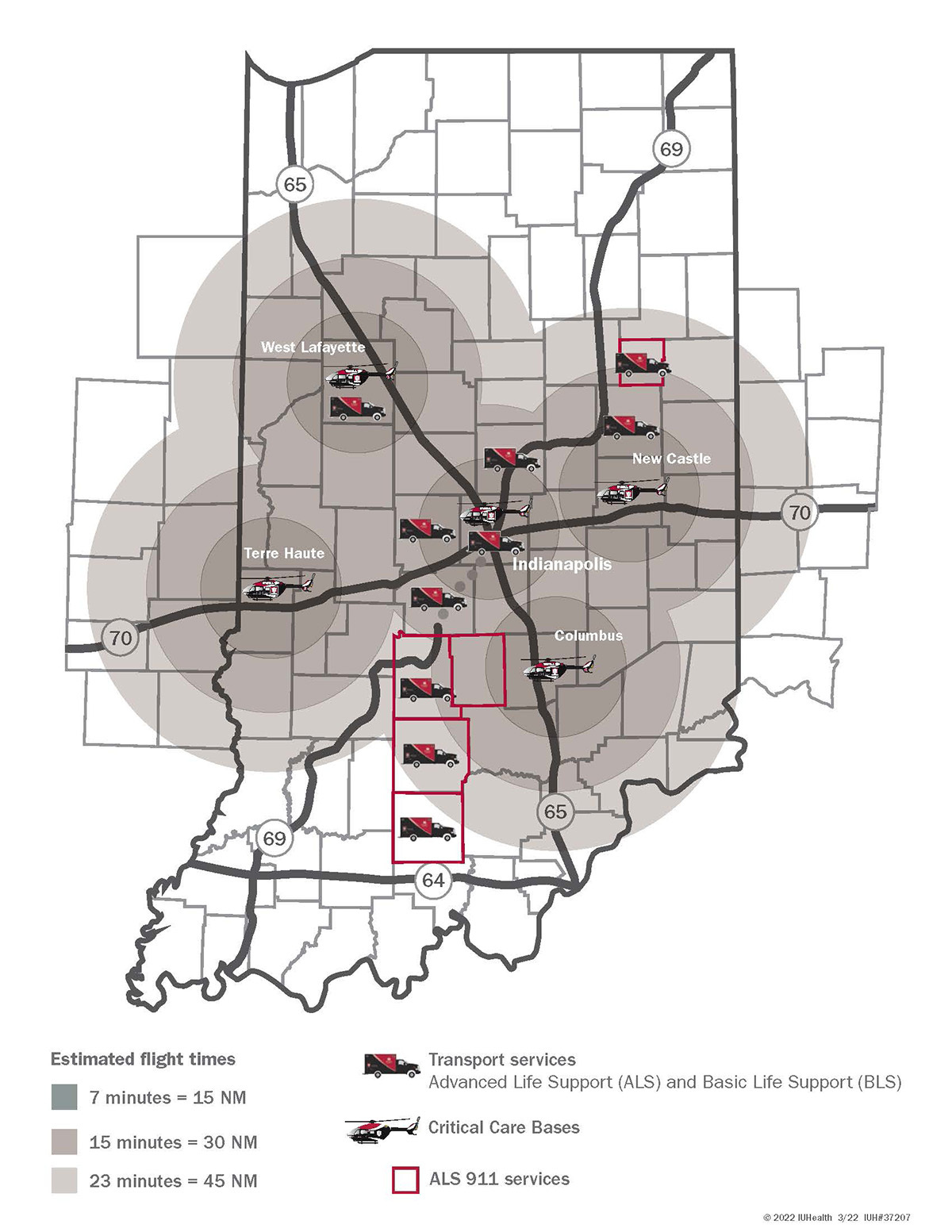

(Story continues below graphic)

Some local governments have tried to offset costs by subsidizing private EMS organizations like LifeLine, but that presents its own problems.

Indiana law says EMS is an essential purpose of political subdivisions. But it doesn’t clarify if that’s at the county, township, or city level, or what level of support they should provide.

Monroe County has relied on private EMS providers since 1986. It used to give the Bloomington Hospital Ambulance Service $100,000 per year, a small fraction of its overall $3.5 million budget in 2009. The county eliminated the subsidy in 2010.

Public services fill some of the gaps in Monroe County even if they don’t eliminate the problem. Monroe Fire Protection District, which is operated by county government, launched a reserve ambulance service last summer to address the local shortage. It operates one full-time BLS ambulance, which Deputy Chief Matthew Bright said responded to almost 400 calls since it began operation on July 16.

Monroe County Emergency Dispatch also calls on neighboring counties for aid and backup. The Brown County Sheriff’s Office said last year it sent EMS to assist Monroe County 273 times.

Summer Brown, Director of Operations at Morgan County EMS, said because of frequent demand from Monroe County her department started limiting its assistance to high-acuity calls.

“I found out we were going down there on calls that even their own ambulances would not have responded to,” she said. “We had conversations with them about how we’re only going on certain levels of calls, and since then they’ve not really contacted us.”

Reimagining EMS

When one Indiana county’s EMS system collapsed, locals saw an opportunity to rebuild.

Private service CARE Ambulance pulled out of Martinsville in 2017, and Morgan County lost its main EMS provider. Local government and LifeLine filled the gap, with the Emergency Management Agency operating two BLS ambulances and LifeLine paramedics tailing them in chase vehicles.

Brown said back then, when you called 911, you didn’t know what you were going to get.

“That was very scary, because it was just kind of thrown together as a band aid while this was going on,” Brown said. “So I think it opened everyone's eyes up, and they're like, ‘We need to do something.’”

Morgan County government approved a small property tax increase to fund a public EMS service. Although it has half the population of Monroe County, it now has more full-time ambulances devoted to emergency response. It doesn’t do transfers.

“I feel very confident in the service that the community is getting now that we have six ambulances to cover what we used to not even know if we had an ambulance to cover,” Brown said.

Public funding insulates the department from some of the financial problems that affect other agencies. Annual pay for a full-time EMT in Morgan County starts at $57,654 while a paramedic earns at least $68,370.

Morgan County Administrative Director Brent Worth said his main challenge running the EMS service is balancing the budget while investing in a workplace where employees want to stay.

“If you have buy in from the employees, then you can run a good agency,” Worth said. “A lot of that comes down to being able to give the employees what they need to do the job right, making sure their accommodations are good and they’re paid as a professional and recognized as a professional.”

David Smith still lives in Monroe County and commutes for the job.

“It's a lot better working for a county because I'm an actual government employee,” Smith said. “I have better pay, I have better benefits, we tend to buy the best stuff.”

Brown also used to work for a private EMS service. She pointed to the company’s leadership as a major contrast with the county department.

“I never saw management or administration,” she said. “They were in the ivory tower, we were down in the street. In this setting, we’re just one door away, and they see us constantly.”

Read more: Latest Braun executive orders target health care affordability, transparency

Of course, Morgan County is just one public agency. Kinney said he wasn’t aware of industry-wide discrepancies between staffing and salary in public and private departments.

“It just seems to be what is the local government’s unit of preference,” he said. “A lot of the times, if they’re able to find the right provider, it may be a private service. It may be a fire service. It may be a county-level EMS.”

Even a well-provisioned EMS agency can face days when it’s stretched to capacity. Worth said there are days when a last-minute call in requires him to switch an ALS ambulance to BLS, but it doesn’t happen often. When all of the trucks are busy, the township fire departments can step in.

Still, Morgan County doesn’t seek help from neighboring counties.

“Since I've been here, we've never called in another service to assist,” Worth said.

Municipal EMS organizations like Morgan County’s represent just 11 percent of providers statewide. Most are fire departments or private services.

While there may be no one-size-fits-all solution for local EMS, Smith said he’d like to see a third, public service like Morgan County EMS back home in Monroe.

“That would require investment,” he said. “That would require tax funders basically to pay for it, like we've done here.”