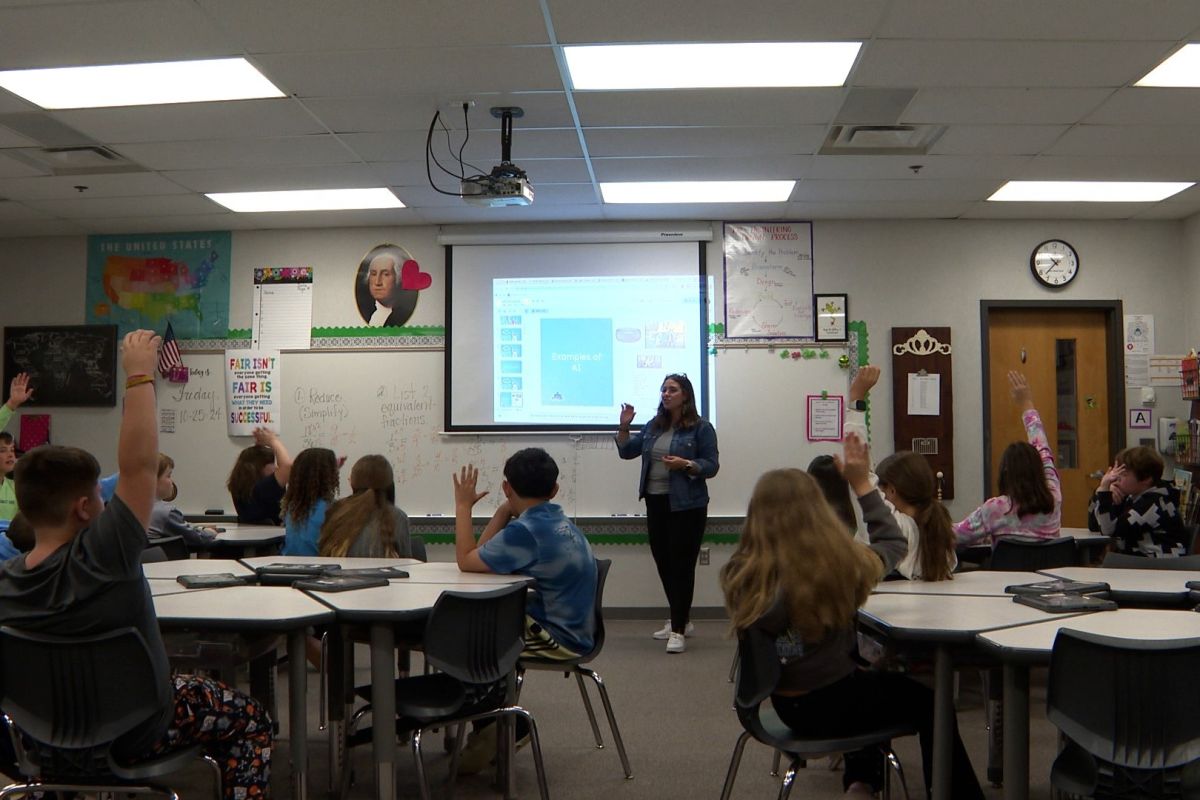

Kristen Publow gives a lesson on AI in her fifth grade classroom at Lakeview Elementary. (Isabella Vesperini)

Teachers in K-12 classrooms are starting to embrace artificial intelligence, and they say while it offers numerous benefits for learning, the technology also creates potential problems for young learners.

A Walton Family Foundation survey shows that AI has increasingly been integrated into education. The survey found that 46 percent of teachers and 48 percent of K-12 students use the AI portal ChatGPT at least weekly — in and out of the classroom. The percentage of K-12 students using ChatGPT has increased 26 percent since last year.

Kristen Publow, a fifth-grade teacher at Lakeview Elementary School, said she wants to give her students an opportunity to learn how to use AI early on.

“I really want to feel that I am doing what's best for kids,” she said. “And I feel like the future of work is changing, and in order for them to be prepared for the future, they need to be exposed to it now.”

Publow gives her students the chance to play around with ChatGPT and ask it to do random things.

“Typing in something like, ‘write a letter to your favorite teacher that includes information about frogs and George Washington,’ because those are two of my favorite things,” she said. “They [students] thought it was hysterical, because it instantly came up with a letter that talked about George Washington and frogs.”

Read more: IU experts discuss White House AI guidelines, express concerns

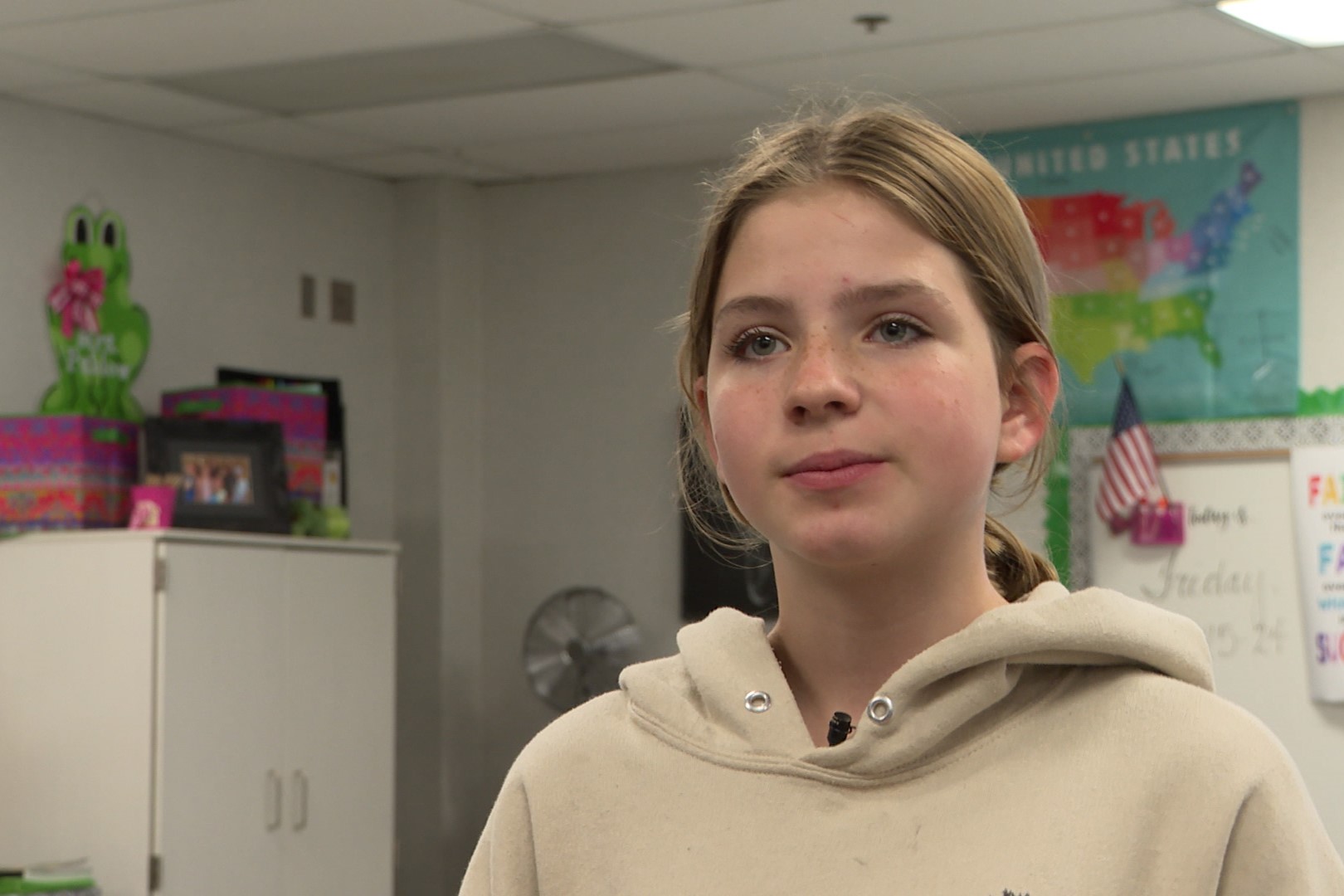

Publow also gives lessons on what AI is and what it can do. Clara Ebelhar was in Publow’s class last year. Learning how to use ChatGPT has helped her apply it to Robotics Club.

“It was like really cool to see how it works because before that, I had no clue how it worked,” Ebelhar said. “And after that [lessons], I knew all about it.”

Lela Merriman was also in Publow’s fifth grade class last year. She especially enjoyed their fieldtrip to see IU’s supercomputer.

“It [AI] never stops learning,” Merriam said. “I feel like it will be really popular, because there's already a new phone that came out and it has so much AI. AI is so, so cool, but it’s also scary how fast it can learn.”

Publow brought in a researcher who taught the kids how to organize data when tracking deer movement.

“Researchers used to sit out in the environment or sit out in the wild, and he explained how he spent hours upon hours upon hours, and that obviously wasn't good, so they created cameras and sensors and used all of that technology to collect the data instead,” she said.

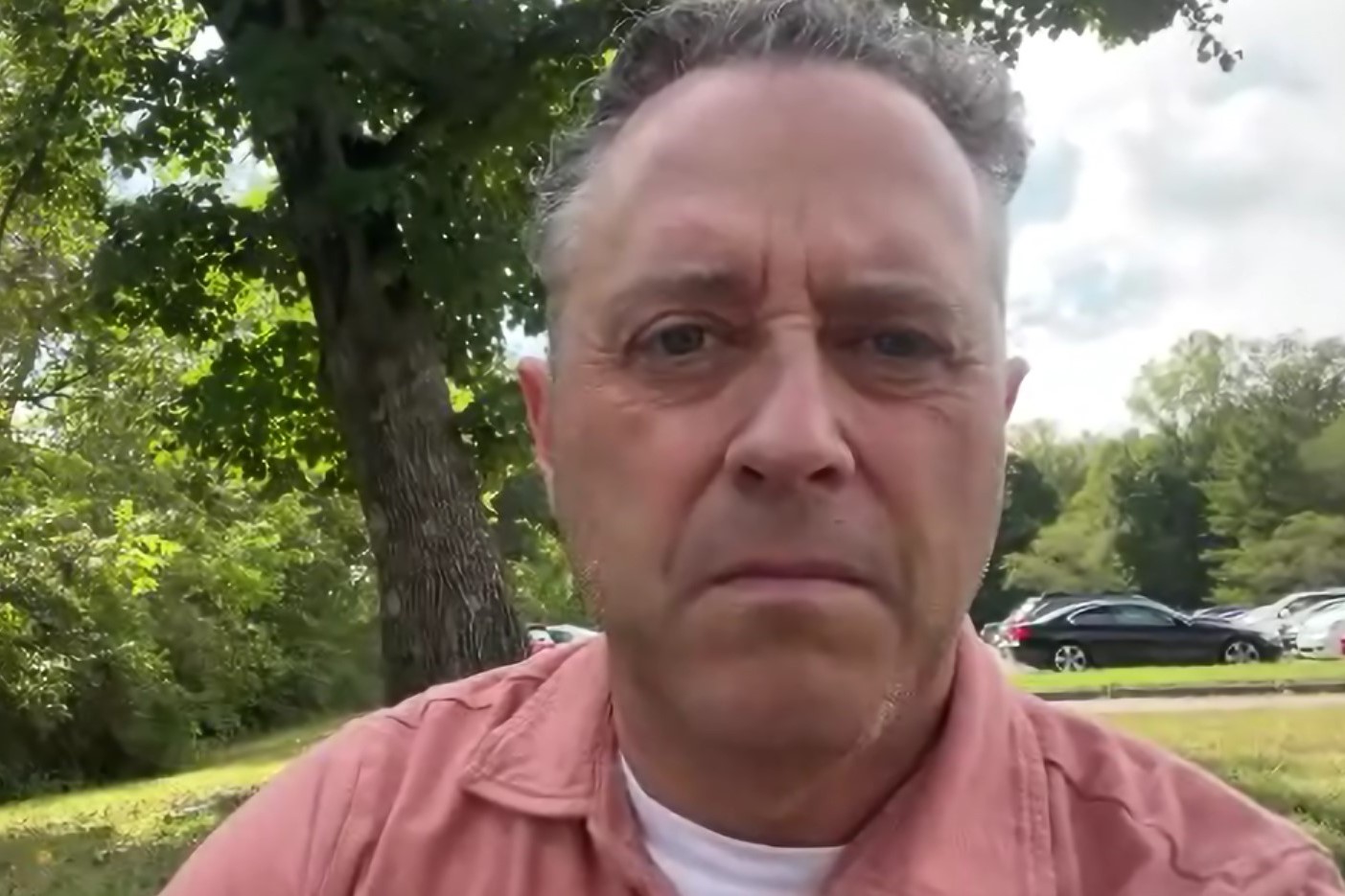

Christopher Kupersmith, an English teacher at Bloomington High School North, uses ChatGPT and Google Gemini after he’s written an assignment to make it easier to understand for students. He also uses AI to simplify readings some students may find challenging and to help him plan lessons.

“I'll explain where we are in a unit, and then say, okay, so here's what we've been doing so far, I'm kind of trying to figure out what would make logical sense to go to next,” he said. “And then I’ll ask it for that.”

Anne Leftwich, Barbara B. Jacobs chair in education and technology at IU, said using AI to complete assignments such as writing is the obvious drawback of the technology in the classroom. But she has a different approach for AI pessimists.

“Instead of saying we're trying to catch the cheating, try and say, ‘how do we catch the learning?’” Leftwich said. “…I've seen some really innovative ways; teachers are asking students to turn in the transcript of how they talk back and forth with ChatGPT, so you can see what questions are the students asking?”

Canvas, a program for classroom management, has Turnitin built into assignment submissions. Turnitin can judge how much of a written work is plagiarized. It can also determine whether someone has used AI in their assignment. Kupersmith said that happens weekly. He asks those students to rewrite and submit the homework without using AI. He doesn’t come down too hard.

“The problem is that AI checkers just aren't advanced enough, and a lot of times they'll identify things as AI that aren't, and a lot of times they won't catch,” he said. “So it's a little bit of a dangerous game to accuse a student of it. But I can read AI from a mile away now, because I use it so much. I'll read the first sentence of somebody's thing, and I'll be like, ‘this is AI,’ and then I'll go check it.”

Until recently, ChatGPT could only access information up to September 2021, and would often produce inaccurate results. OpenAI announced in an X post last year that ChatGPT can now access information from any time on the internet. But Kupersmith reminds his students that AI isn’t flawless.

“It's a great place to get ideas. It's a great place to get feedback. It's a great place to retry to get an understanding of something you're not quite getting from your teacher,” Kupersmith said. “But we all know that it can say some wrong things, it can do some crazy stuff.”

Some teachers are concerned about not having time to teach kids how to use AI, let alone learn how to use it themselves. But Publow hasn’t had any issues experimenting with Google Gemini to help her create a rubric that would’ve originally taken her weeks to do.

“It basically just makes your life easier,” she said.

The Walton Family Foundation survey found that 56 percent of teachers have not received training on how to use AI chatbots but would like to. The survey showed 32 percent of teachers are not using AI because of a lack of training. But teachers who do use AI save an average of 13 hours a week. The study also found that 59 percent of teachers who don’t know how to use AI are favorable to the technology, while 72 percent of teachers who do know how to use AI are favorable to it.

“The thing is, students are so good at figuring it out, whether it's just clicking a bunch of buttons because they're not worried about breaking something – that sometimes has a big (part) in it,” Leftwich said. “They're just inquisitive learners; they want to figure it out.”

Once kids experiment on their own, it’s easy for them to share the results and how they did it with others in the classroom.

“If I tell you, ‘Hey, I know that you have to create a ton of new assessments for your classroom. Let me show you how you can do that in ChatGPT and only take five minutes of your time,’” Leftwich said. “So then once you start seeing those things, then you start saying, well, what else could I do?”

Leftwich compared AI to how K-12 education reacted to the calculator. Students, of course, need to learn how to do math with just a pencil and paper, she said. But shunning the calculator altogether was misguided.

“If we're not preparing students to be able to go into the world with this particular skill set, I feel like we are doing them a disservice,” she said.

Read more: Social media could be harmful to young children

She praised the Monroe County Community School Corp.’s approach.

“First of all, they haven't banned access to AI, which I think is incredible,” Leftwich said. “I know that a lot of schools are just like shutting it down because they can't figure out how to (use it), and MCCSC has not done that, which I think is a real credit to them.”

Alexis Harmon, MCCSC assistant superintendent of curriculum, assessment and instruction, said in a statement the district’s Curriculum and Technology working group is still deciding how to incorporate AI into their curriculum.

“Through this group and our teachers, we will be identifying resources, developing trainings and then lesson plans,” she said in the statement. “We want to ensure we have the best tools and experiences to offer students, and that ultimately anything we do, enhances student learning experiences.”

Given how widespread AI is, Kupersmith also doesn’t think it’s a good idea to keep students away from it. He prefers to directly address the issue in class and teach students early on how to properly use it as a tool.

“Sometimes I actually am the one who is ultimately introducing them to AI, which feels a little bit like I'm opening Pandora's box,” he said. “But again, they're going to come around to it eventually.”

Crafting tasks for AI is itself a learning experience, Leftwich said.

“It's trying to be thoughtful, coming up with the questions, figuring out what you want to investigate, then using the AI,” she said.

She gave an example of how she has used AI to teach story writing.

Read more: AI Goes Rural brings artificial intelligence to underserved schools

“We put the first two scenes into AI, and then we said, what might be some ways that this character could develop? What could happen? Or how could he show examples of perseverance?” she said.

Leftwich has also taken part in IU’s AI Goes Rural initiative. She’s worked with students around the state to implement AI into their curriculum.

Younger kids have been increasingly exposed to screens and social media for longer hours at a time, which can lead to less sleep and behavioral problems. An excess of screen time can also cause children’s attention spans to shorten. Incorporating AI-related activities in the classroom would theoretically mean even more screen time.

Leftwich said the best way to combat this is to use AI thoughtfully and in moderation.

“Now, if you're having students look at YouTube videos all day, every day, and then it's like clicking to the next one, to the next one, to the next one, your brain is getting triggered for that,” she said. “We have to think more critically about what our assignments are, or how we are using the technology.”

Kupersmith recognizes that AI isn’t going away.

“There is a world in which there could be some really, really interesting collaborations between humans and AI,” he said. “We just have to find the right balance.”