Data centers, like this Google center in Mayes County, Oklahoma, require 24/7 power — and a lot of it. (Courtesy of Google) (Courtesy of Google)

Companies like Google, Meta, Microsoft and Amazon are building large data centers in Indiana for artificial intelligence. Each one requires power 24/7 — and a lot of it.

But Indiana utilities weren’t anticipating this when they made plans to get more power from sources like wind and solar. Data centers could delay utilities’ efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Data centers present an economic opportunity for Indiana

If there’s one thing Indiana is known for besides corn, it’s business. Former Gov. Eric Holcomb has said these data centers will secure Indiana’s place in the economy of the future.

Fort Wayne Mayor Sharon Tucker hopes residents on the city’s southeast side can get a slice of that pie. She said the area hasn’t seen much investment since the early '80s.

Google’s proposed data center will likely employ no more than 200 people, but she said it will have ripple effects.

“It has already turned the heads of other developers to go, ‘Well, if Google's going there, perhaps we can go there as well, right?’” Tucker said.

Can utilities meet this high demand for energy with clean power?

But while data centers could present an opportunity for Indiana cities, they’re a huge challenge for the state’s utilities.

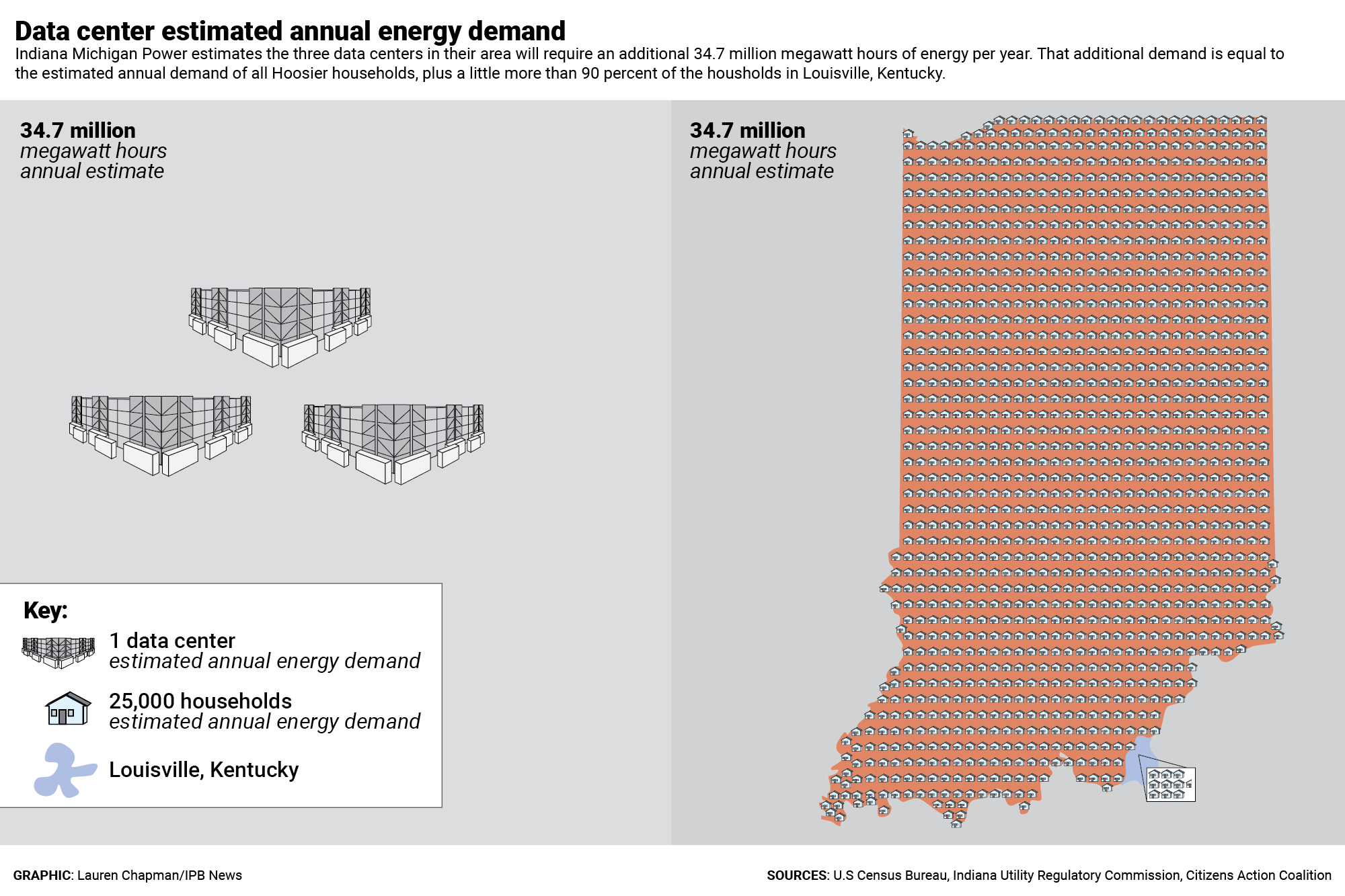

Ben Inskeep, with the consumer and environmental advocacy group Citizens Action Coalition, said we don’t know for sure how much energy these data centers will use, but documents from the utility Indiana Michigan Power show it's a lot.

“These data centers, just in Indiana Michigan Power’s service territory in Indiana, could use more energy each year than all 6.8 million Hoosiers use in their homes each year. So we're talking a scale that people probably can't comprehend," he said.

Inskeep said if utilities want to meet that large demand for power around the clock, it’s unlikely that cleaner sources like wind and solar can do that alone.

But to avoid the worst effects of climate change, scientists say we need to significantly reduce emissions by 2030.

“If any of that energy, a single megawatt hour comes from fossil fuels — that's increasing our emissions," Inskeep said.

So far, fossil fuels are exactly what Indiana utilities have in mind — whether that's building new plants or keeping old ones around.

Duke Energy cited data centers as one reason for keeping its Gibson coal plant open longer. NIPSCO plans to build at least one large natural gas plant, if tech companies sign contracts for their centers. Indiana Michigan Power is considering either purchasing or building new natural gas to meet their demand.

There’s not a lot of time for utilities to figure out how to power data centers before they come online and meet climate goals.

“The growth of data centers around the U.S. is one of the most challenging opportunities that's come up for utilities in recent years," said David Porter with the Electric Power Research Institute or EPRI.

Tech companies could work with utilities to create some wiggle room

EPRI is helping tech companies figure out how to manage energy use at data centers and solve some of these problems. He said there are ways to make data centers less of a strain on utilities and curb emissions.

“There's three main things that take place inside a data center for AI. One is building the model. Two is training the model. And then the third is the actual execution of the model where users are querying it for information,” Porter said.

Porter said the first two can often be done at times when the demand for energy is lower, putting less pressure on the grid.

They also have backup generators — so they don’t always have to use power from the utility. EPRI is researching ways to swap out the diesel fuel those generators use with climate-friendly alternatives like vegetable oil or biodiesel.

All of these things give utilities more choices in how they serve data centers — and, potentially, greener ones.

And that tight timeline data centers have? Porter said tech companies don’t actually need all that power all at once.

“Even when they finish getting all the steel and the concrete in the ground and say the buildings are finished. The computer load is not there yet," he said.

Porter said it can take up to four years for a data center to get fully up and running.

Most of these big tech companies also have a vested interested in going green — Google, Meta, Amazon and Microsoft all aim to go net zero or have negative carbon emissions by 2040.

According to the Indiana Energy Association, which represents investor-owned utilities in Indiana, most of these tech companies are hoping to use some renewable energy to power their data centers.

Some are looking into small nuclear plants. But Porter said that technology is at least a decade from becoming commercially available. The first one hasn’t been built yet. The project seen as the most viable — backed by the U.S. Department of Energy — was canceled in 2023 after almost a decade and nearly $9 billion in costs.

In the meantime, Porter said natural gas will likely fill that gap.

Join the conversation and sign up for the Indiana Two-Way. Text "Indiana" to 765-275-1120. Your comments and questions in response to our weekly text help us find the answers you need on climate solutions and climate change at ipbs.org/climatequestions.

Advocates urge utilities not to choose AI data centers over the planet

The question is: Can the planet afford this detour in our path to significantly cut greenhouse gas emissions?

Citizens Action Coalition's Ben Inskeep said absolutely not. He said our first priority should be to live — and generate energy — in a way that helps us achieve a stable climate.

“If we can have some data center load growth within that — OK, great. But if not — then no, we should not be doing this aggressive expansion of AI data centers," Inskeep said.

A state senator has proposed a bill, SB 135, that would require data centers to disclose their electricity use. But if it doesn’t get bipartisan support, it will likely fail.

Rebecca is our energy and environment reporter. Contact her at rthiele@iu.edu or follow her on Twitter at @beckythiele.