A vial of Moderna's coronavirus vaccine at a Bloomington vaccination site. (Alex Paul, WTIU/WFIU News)

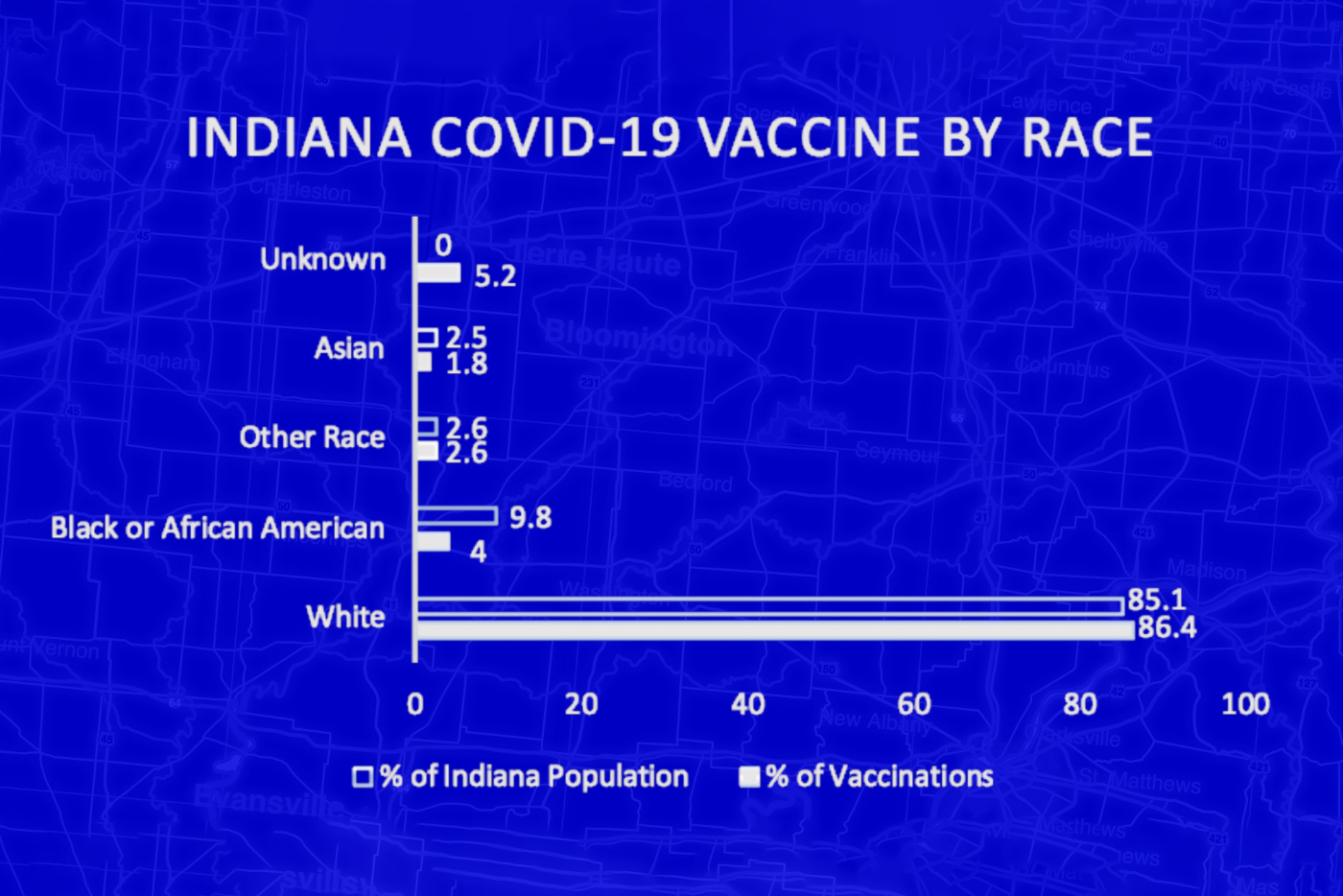

Data from the Indiana State Department of Health reveals a lower proportion of Black Hoosiers have received the COVID-19 vaccine.

While some experts attribute that to the greater proportion of white doctors, available data reveals Black and African American Hoosiers have received 4 percent of all COVID-19 vaccines despite making up one-tenth of Indiana’s population.

As the state continues to expand vaccine eligibility, racial disparities and hesitancy in the Black community are becoming apparent.

Experts say distrust is rooted in years of systemic racism in the American medical system.

Tara Morris, who heads the Minority Health Coalition of Elkhart County, remembers when she first heard of the coronavirus nearly a year ago. She was planning other programs, but quickly realized this virus would require her full attention.

At first there wasn’t a lot for her to do.

“All we could do is stand by and watch the numbers increase,” she said. “Watch people get sick because of lack of information on what to do, you know, just waiting on our localities and municipalities to get it together.”

The coalition in Elkhart County works with 22 others across Indiana to reduce chronic disease and health disparities among racial and ethnic minorities. That was a tall task pre-pandemic, but the challenges are even more apparent now.

Data shows Black Americans are far more likely to be exposed to COVID-19 from their workplaces. Another study found that Black, Hispanic, and other racial minority groups were more likely to be hospitalized after contracting the virus.

Statistics like those aren’t surprising to Morris. She said the pandemic presents an opportunity to address problems which have persisted for decades.

“We are so far behind, in addressing what's in front of us when we look at these health disparities,” she said. “It's right here in our face. So what do we want to do?”

Tony Gillespie, the vice president of public policy and engagement for Indiana’s Minority Health Coalition, agrees.

“You can't address 100 years of mistrust of public health and healthcare period; you can’t address it in a webinar,” he said. “There are a lot of other things that have to go along with that.”

For Gillespie, much of the distrust stems from historical events that have eroded it in the Black community. He says decades-long unethical medical research in Tuskegee, Alabama, drove a wedge in the community that’s been difficult to repair.

Data supports Gillespie’s assertion.

Local Testimony Contributes To Broader Narrative Of Distrust

Other systemic barriers make it more difficult for Black and other minority populations to trust public health officials and health systems too. Not all of them are out of state.

Late last year, a Black Indianapolis physician, Dr. Susan Moore, published a series of posts and a video lying in her bed at Indiana University Health’s North Hospital, describing how she was treated by a white doctor.

“I was in so much pain from my neck. My neck hurt so bad,” she said, fighting back tears with an oxygen tube draped over her face. “I was crushed. He made me feel like I was a drug addict, and he knew I was a physician.”

Just over two weeks after posting the video, Moore died.

On Christmas Eve, IU Health President Dennis Murphy issued an assurance IU Health would conduct an outside review, but defended the care Dr. Moore received, writing in part:

“I am fully confident in our medical team and their expertise to treat complex medical cases. I do not believe that we failed the technical aspects of the delivery of Dr. Moore’s care. I am concerned, however, that we may not have shown the level of compassion and respect we strive for in understanding what matters most to patients.”

“We really have to think about the systemic racism, the systemic inequalities, the structural inequities that have set people up to be at a disadvantage over their entire life course,” said Dr. Elaine Hernandez, an assistant professor at Indiana University. “The onus really needs to be on our medical institutions to be trustworthy.”

Gillespie recognizes experience like Moore’s reinforce distrust—especially with a new vaccine.

“Healthcare is a big decision,” Gillespie said. “A vaccine that didn't exist before a few months ago is the biggest thing that's going to happen in our lifetime.”

He insists such intervention “comes a lot of speculation.”

‘Something Has To Be Done’: A Pastor’s Call To His Congregation

Dr. Clyde Posely Jr., a pastor at Antioch Missionary Baptist Church in Indianapolis, had similar concerns. He knows firsthand how severe this virus can be. His father, Clyde Posley Sr., died six weeks ago due to complications from the coronavirus.

Posley said his father was always present in their family, but the virus took that away and kept them away. “

“COVID forced my father in death into an antithetical expression of who he was in life,” he said. “None of his four remaining children, none of us could go see him.”

Posley says it took him a long time to process his father’s death.

“I couldn't see him in the hospital. The next time I saw my father was in a pine box,” he said. “So something has to be done.”

Posley understands the systemic issues and underlying hesitation is real, but believes now is the time for solutions.

That’s why, after reading up on clinical trials and conducting his own research, Posley began advocating for his congregation and those in the community to receive their shots.

“This is what we need to do, and we need to we can't simply talk about it,” he said. “Whatever a person's political views are, we did not attack this COVID the way we needed to, and so we need to attack it the way we need to now.”

Posley believes this is where he’s being called after his father’s death. “If the Lord would have called me home today, I want to go home knowing that I was giving my life to thing that was most relevant at this moment.”

He’s since received both doses without complications, but admits there was trepidation when heading to his first appointment.

“These things are real,” he said. “If I didn't believe them, it would mean that they didn't happen.”

Morris also received her first dose of the vaccine a few weeks ago. She, too, was hesitant and wanted to read the clinical trial research before committing.

“At some point, we’re going to have to decide to put our faith in something, because people are dying and you don’t tie from a hoax,” she said.

All agree expanding vaccine access, dispelling misinformation and quelling anxiety are important steps.

But few things can replace individual conversations with friends, neighbors, and family members who already have received the vaccine.

“However many different people we need to bring together in a collective to talk about this and to work through the fear and the anxiety, we're going to do it,” Gillespie said.

He insists all communities and populations face different barriers and challenges.

“People are nuances, communities are full of nuances,” he said. “We must look at [the] community, and figure out how we’re going to increase vaccines.”

Posley insists there isn’t a separate vaccine for white and Black Hoosiers.

“We have to keep in public health,” Gillespie said. “There’s not a group of people that you’re doing something for or doing something to. It’s a group of people that you’re doing something with.”

Morris agrees, and believes unity and disseminating proper information are the only ways to increase buy-in.

After receiving her first dose, the initial anxiety felt is gone, and she’s now shifting her focus to getting others vaccinated.

“[It] is behind me right now,” she said. “I know I have that the second dose coming up, but it's going to be okay. It's going to be okay.”

Morris says she now feels relief that she can remain present for her family and grandchildren. Her hardest sell might be her 85-year-old father, but she’s not going to stop trying.

“He is a work in progress, ok?” she said, laughing.

WFIU/WTIU News Resarcher Cathy Knapp contributed to this story.

For the latest news and resources about COVID-19, bookmark our Coronavirus In Indiana page here.