Federal regulations promise patients easier access to more of their health care data starting Oct. 6, but concerns about privacy and provider compliance loom large. (Leslie Walker / Tradeoffs)

Starting Oct. 6, medical providers must begin giving patients electronic access to more of their health care data than ever before. But the federal regulations forcing this change are fraught with implementation challenges and privacy risks. Major industry groups, including the American Medical Association and American Hospital Association, are calling for more time to comply.

Dan Gorenstein, host of the health policy podcast Tradeoffs, spoke with Micky Tripathi, the federal official overseeing this push to democratize America’s health data, about its promise and perils. Tripathi is the national coordinator for Health Information Technology at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

DAN GORENSTEIN: So Micky, at a super high level, why is Oct. 6 a big day?

MICKY TRIPATHI: Oct. 6 is a big day because we're saying if data is electronically accessible — meaning it's on a computer system somewhere in your hospital — you're required to make it available electronically. Patients deserve more health care data, right? That's the basic premise. We're saying it is electronic. It's digitally there. So make it available.

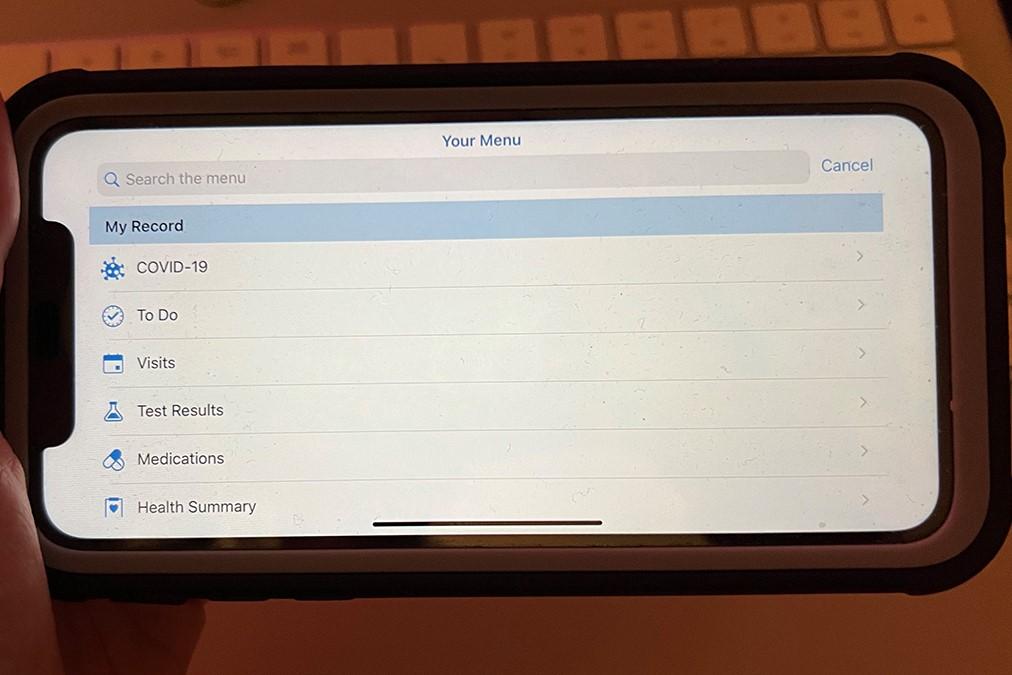

GORENSTEIN: What's a patient going to be able to do on Oct. 6 that they could not have done on Oct. 5?

TRIPATHI: Yeah, so it's gonna vary a lot, but conceptually, starting on Oct. 6, a patient ought to be able to see that what is offered to them or available to them is more than, you know, your first name, last name, your address, your allergies. So for example, you might start to see a whole set of notes — nursing notes or my operative notes from my last surgery or some of the images from my last imaging — those are starting to be made available to you electronically.

GORENSTEIN: Just a quick housekeeping question, Micky. Already on Oct. 5 patients have the right to say, “You need to share my data with me,” right?

TRIPATHI: Yes, you can walk into that hospital today and [demand all of your records] and what they'll say is, “Well, your patient portal has a whole bunch of it, and then for the rest of it, we will provide you a paper copy.” You're able to, sort of, get this little straw, but what [you] want is the entire river [of your electronic health information].

GORENSTEIN: The difference between Oct. 5 and 6 is now I get a bigger straw. It's the Big Gulp straw.

TRIPATHI: Yes, so that's the concept and that's what we want to get to, and the reason I'm hedging on that is that we're starting to get into areas where the data is really not standardized and it's really messy.

GORENSTEIN: Messy how?

TRIPATHI: We've made a choice to say, we can't wait to have all these data elements neatly and crisply defined, so they fit into that straw. So you could get it in one format from one hospital, in another format from another hospital. And right now we're saying that's fine. We have to live with that for now. The important thing is to make it available.

GORENSTEIN: This sounds like a very laissez faire approach from the federal government, Micky. Why not be more prescriptive, tell hospitals how you want this data formatted to make sure it’s really useful for people?

TRIPATHI: If we end up deciding that more regulation is needed to make that happen on an ongoing basis, those are the kinds of things that we always consider. But we also don't want to overregulate because we don't want to jump ahead into areas that are still very dynamic. Because we could get it precisely wrong in many ways as the federal government, right? And undoing that is then like, “Oh, great, you've imposed a floppy disc 3.5 standard on an industry that has jumped ahead to fiber optics.” So let's be cautious here and see what the market can do and then be judicious in how we intervene.

GORENSTEIN: What about hospitals? What does Oct. 6 mean for them as systems, these behemoths with massive back office operations?

TRIPATHI: Yeah, I mean, it's definitely very complicated. The first thing they need to do is [ask] where is all this patient data? And then how am I gonna mobilize that in as close to real time as possible when Dan comes knocking and asking for that information?

And that's not an easy problem to figure out because in a hospital system we tend to think about the electronic health record system, Epic, Cerner, whatever it is. But hospital systems also have lots of ancillary systems — chemo dosing, cardiology, anesthesiology systems — that could be 10 years old, 15 years old. Those systems were never designed for, “Oh, we have a query coming in from Dan. We need to immediately have the ability to go and get that information, assemble it with all the other pieces of information and present it back to Dan in the portal in real time.” So thinking through all of those policies, capabilities and workflows [is] complicated. We appreciate that it's complicated.

GORENSTEIN: What signs of gaming, Micky, are you looking for from health systems? If a hospital wanted to get around the real intent of this rule, how might they do that? And I ask that question because we've seen other data laws, like hospital price transparency, and we've seen health systems be really reluctant to comply.

TRIPATHI: It's a fair question. My office defined eight exceptions that allow a provider organization to say, “Well, I know I'm required to make this information available; however, I can't for one or a couple of these eight reasons.” One is privacy. Another might be that you're not able to deliver it to them electronically — what we call infeasibility. So there's certainly opportunity for people to interpret things, you know, more broadly perhaps than is intended.

GORENSTEIN: And what's the stick that you have to beat them back?

TRIPATHI: In terms of the stick, what is the stick? Well, it's complicated. The reality of this is we're not doing real-time monitoring of this. We don't have the, sort of, exception police. On the other hand, [my office], the Office of the National Coordinator, has a portal where you're allowed to file complaints. And we take those complaints and we do an initial vetting of them and then we send them over to the Office of Inspector General, who's responsible for enforcement.

GORENSTEIN: What are the stakes here if these efforts fail?

TRIPATHI: I mean, the stakes are that you show up someplace where you need care and information that is critical to that clinician on the ground is not available to them. Showing up in the emergency department and being prescribed penicillin when you're allergic to penicillin. Right now, how do they figure that out? They ask you. Well, what if you're in trauma? What if you're elderly? We never know when we're gonna be in that situation where a clinician doesn't know everything about us and they're making decisions on the fly because they have to go with the best information they have.

GORENSTEIN: So this Oct. 6 change, it’s the latest phase of a much larger push that the federal government and industry have been making for the last decade to put our health care data to better use.

Micky, can you zoom out and kind of map this journey for us? Where have we been, where are we now and where are we going next?

TRIPATHI: Well, if you just think about this 10-year journey you were just describing, in 2010 we invested as a country — as taxpayers — about $30 to $40 billion moving the whole system from paper-based to electronic. An amazing accomplishment over a relatively short period of time. And that's kind of what we did over these last 10 years, like, let's just get the electronic health records in place so that everyone has them and create this digital foundation. But now we have the opportunity here to create an open ecosystem as we call it, where data can flow on demand and systems are interactive in a way that they're not today.

GORENSTEIN: On the one hand here, Micky, you're giving patients easier access to their data, but at the same time, you're opening the door up to privacy and security questions, at least theoretically.

How's your team thinking about those kinds of risks and trying to mitigate them?

TRIPATHI: Those are very real risks. So the first thing I would say is that for patients in particular getting their information, they need to be incredibly diligent about the apps that they're using for their health care information. Instead of doing what you and I do all the time when we download an app, user agreement, click, click, click, click, click. Just get me to the damned app, please. You know, you can do it for all your other stuff, right? Don't do it for your financial stuff. But definitely don't do it for your health information stuff.

Here's the problem. Once the information leaves the boundaries of HIPAA, it no longer has the kind of protections that, unfortunately, people think it does have. They don't realize that HIPAA attaches to the data only when it's in the hands of certain organizations, like a health insurer, like a hospital, like a doctor. But the minute that that gets into an app, it no longer has those protections.

GORENSTEIN: So you're basically saying here, Micky, that HIPAA, the main federal law that protects patients’ health care data, just doesn't apply if a patient, for example, breezes through a user agreement for some third-party app and doesn’t realize they just gave the green light to sell all their health data. They’re out of luck. Are you guys doing anything else to try to protect people?

TRIPATHI: So what we're trying to do is first, impress upon everyone the need to educate patients, because we strike a balance here, right? You don't want to say, well, “We're not gonna provide information to patients.” We want to be able to say, “We are providing information to patients because we think that they will be in a better position to participate more actively in their own care and benefit from that.” But that benefit comes with certain risks and they need to understand those risks, and there’s an obligation on providers and others to educate patients about it.

GORENSTEIN: But, Micky, this could be a disaster for patients.

TRIPATHI: So it's not just health care data. It's like all other data. We just need to recognize that patients need to be very, very, very diligent and cognizant of the fact that that information now is in a different sort of status. And they are the ones who actually have the primary responsibility for making sure that it doesn't get into apps that they don't trust.

One of the things I think we also need to acknowledge here is that people can make inferences about your health from data that doesn't live in your electronic health record. Let's say I wake up with a backache, I reach over, pick up my Google Pixel, do a search on, you know, back strain, and then the next day, you make an appointment with your provider. My Google Pixel phone knows all of that, right? So you get my point. Not to scare you, but all of us need to recognize there's a lot more information out there that people can make inferences about than we probably appreciate, and your health status is a part of that.

GORENSTEIN: Too late, Micky. We're scared.

TRIPATHI: Don't be scared. Be diligent.

This story comes from the health policy podcast Tradeoffs, a partner of Side Effects Public Media. Dan Gorenstein is the executive editor for Tradeoffs, which ran this story on October 6.