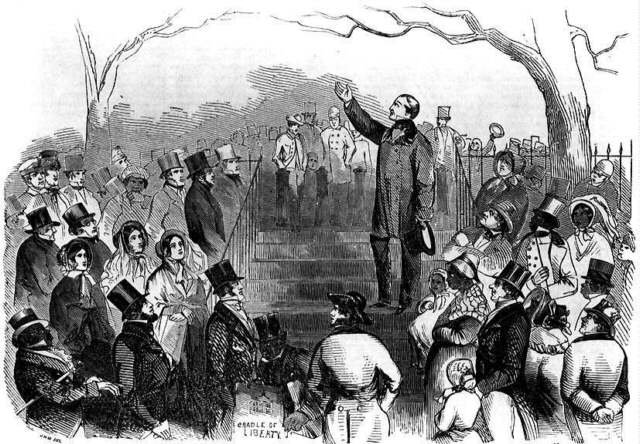

The illustration is from a popular nineteenth-century publication. It shows reformer Wendell Phillips (1811-1884) addressing an April 11,1851 meeting to protest the case of Thomas Sims, a fugitive slave being tried in Boston. A fiery and persuasive orator, Phillips was a member of the Boston Committee of Vigilance that tried to prevent Sims from being returned to slavery. The attempts failed and on April 13, United States marshals marched Sims to a ship that returned him to Savannah, where he was publicly whipped.

One of the most courageous leaders in the abolitionist movement was Hoosier Stephen S. Harding. Harding was born in Palmyra, New York, in 1808—coincidentally, the year that the framers of the Constitution had marked as the beginning of the end of the peculiar institution.

The compromise in Article I, section 9, specified that in 1808, Congress would be allowed to prohibit the importation of slaves. But the divisions between North and South only grew deeper with each decade of Harding’s life.

In 1820 when Stephen was 12 years old, his parents and twelve siblings moved to Ripley County in southeastern Indiana. The new state of Indiana had outlawed slavery in its own constitution in 1816, but the Hardings had moved to a region heavily settled by families from slave states, many of whom remained sympathetic to slaveholding.

After finishing only nine months’ worth of school, Harding became a teacher at the age of 16, and then studied law. He became a lawyer at the age of twenty—the same year he made a business trip for a client to New Orleans by steamboat. While in Louisiana, Harding visited a plantation for the first time and saw firsthand the Crescent City’s slave markets.

After eight months in the South, Harding returned to Indiana, changed by what he had witnessed. By 1830, he had dedicated himself to the abolition movement, reading voraciously and listening to all of the speeches he could on the subject. Harding began to speak out against slavery, with a “deep, resounding voice and convincing manner of address.”

In a time when most Hoosiers, especially those in the southern part of the state, had no interest in abolition and little or no sympathy for slaves, Harding tried to persuade hostile audiences. He spoke in front of groups full of armed men and to those who accused him of treason for advocating abolition, even as friends tried to dissuade him out of concern for his safety. Harding believed that if he could describe, in detail, the true horrors of slavery, that northerners, most of whom had a superficial knowledge of the institution, would come to share his disgust and convert to the cause of abolition.

Harding did not confine his work to Indiana, traveling around the country giving speeches to organized anti-slavery societies and meeting with other abolitionist leaders. Harding was not a radical, moral abolitionist like William Lloyd Garrison, however. Garrisonians promoted abolition at all costs, even disunion between North and South. Harding believed that slavery was unconstitutional, and he believed the framers meant for it to survive only temporarily, to keep the thirteen colonies together, and then “be automatically abandoned as an economically unsound institution” (p. 216).

Harding lived to see anti-slavery sentiment grow in Indiana in the 1850s, as northerners became outraged at attempts to expand slavery into western territories like Kansas, and he became active in the Free Soil party. By 1856, he had become a member of the newly formed Republican Party, viewing it as the nation’s best hope for abolition. This supporter of Lincoln took on two posts during the Lincoln presidency—first, as governor of Utah Territory and then as Chief Justice of the Colorado territorial court.

A Moment of Indiana History is a production of WFIU Public Radio in partnership with the Indiana Public Broadcasting Stations. Research support comes from Indiana Magazine of History published by the Indiana University Department of History.

IMH Source Article: Etta Reeves French, “Stephen S. Harding: A Hoosier Abolitionist,” Indiana Magazine of History 27, no. 3 (Sep. 1931): 207-229.