Yalie Saweda Kamara: Having people see you and hear you, if even they don't agree with you, just hear you and see you, that spirit can carry into your writing. And what you feel like you can and cannot write, and the boundaries that you push within yourself.

Alex Chambers: Yalie Saweda Kamara is a poet. Her full-length collection just came out. The teaching in the community, as well as the classroom, that's also central to her work. This week Yalie and I talk about the importance of community for being a writer, how her life changed when she moved to the Midwest and more. That's coming up after this.

Alex Chambers: To be a poet, Rainer Maria Rilke said, "What you need is solitude, great inner solitude, that, is what one must learn to attain. To be able go within and meet no-one else for hours." But it ain't easy, in certain periods of our lives, just the logistics are almost impossible. We have roommates or families, colleagues at work. In some ways remote work has probably helped some people have more alone time, for better or worse. But that brings us to the other dilemma, even if we're not around other people, we still have our devices. We can check our email every couple of minutes or-- wait I got a text, hand on. Oh, and there's so much context out there, audio books, YouTube videos, social media, and radio and podcasts. They all keep us company in a way and they also distract us from that great inner solitude Rilke was talking about. I don't blame us, it can be lonely, it can be scary almost. Tasting that inner freedom, which is also our aloneness, can leave us unmoored, which is why we like to distract ourselves.

Alex Chambers: I've always thought, that to be a writer, you had to be able to go inwards, cultivate that solitude. I don't think the poet, Yalie Saweda Kamara would disagree. But as a working poet, which is to say, as someone who writes, both her own work and leads workshops, and teaches at a university, Yalie also cultivates community and collaboration. For example, in 2022 she became the Cincinnati and Mercantile Library Poet Laureate. As part of that, she invited people from across the city and Northern Kentucky, to write about what they've discovered in Cincinnati. Then she assembled their words into a poem and it was displayed at Blink, which is the city's biannual Festival of Light and Art. She's working on another series of polyvocal poems for the next Festival, this Spring. That's just one example of Yalie's work in the community.

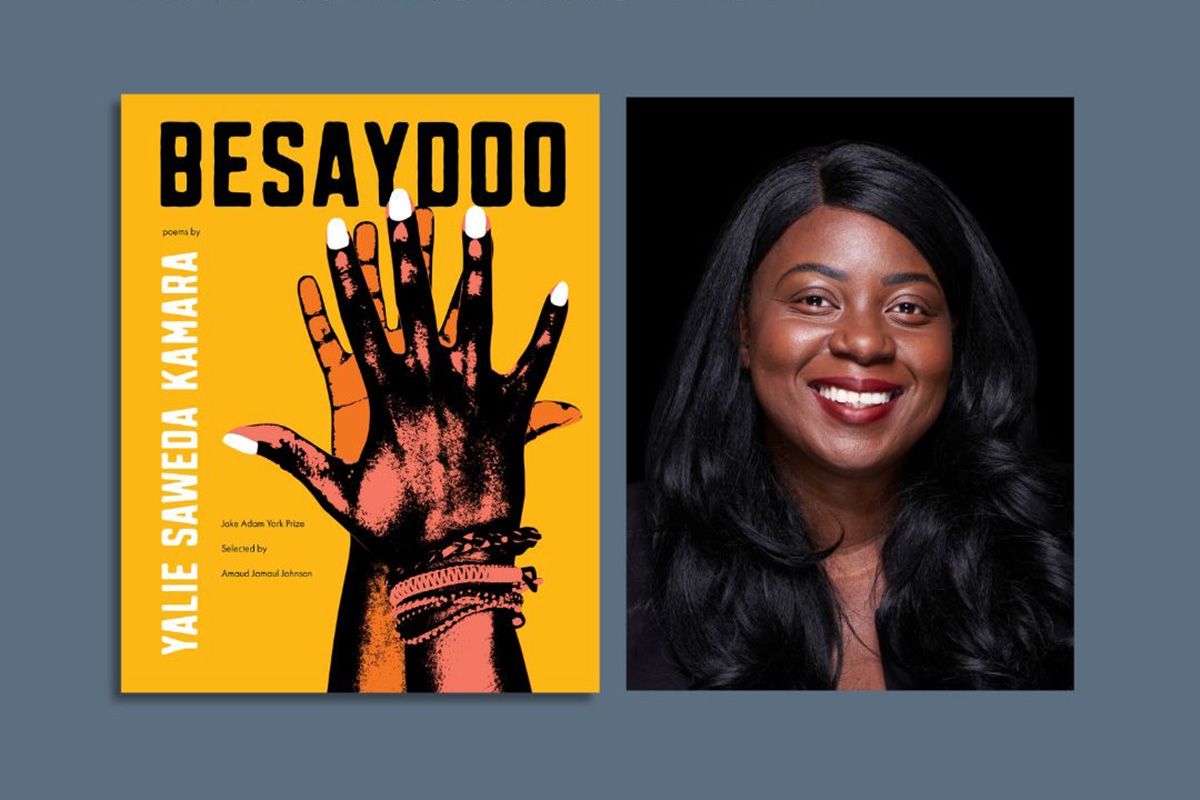

Alex Chambers: She came up as a poet through 826 Valencia and Youth Speaks, two writing programs in San Francisco for young folks. And her first full-length collection has just come out, it's called "Besaydoo". Besaydoo won the 2023 Jake Adam York Prize and it's been featured on a lot of most anticipated book lists in the past few months, including Lit Hub and a mention in the New York Times book review. If you're curious about the title, don't worry, we talked about it. But I started by asking her about the solitary work of writing poetry and how that interfaces with the very public work of teaching.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: So, in terms of thinking about the balance between poetry and writing being an isolated and solitude thing, which it is, versus teaching, I think for me I really benefit from that inner plan. Someone who does like to write on their own, and not just on my own, I know that my practice has shifted by virtue of the Laureateship, and where a lot of my reading does happen in community now too. And in so far as wanting to participate or taking time to participate in the writing prompts and activities that are being facilitated to work and write alongside folks, that I'm blessed to be working with. I also I think that teaching keeps me from being super weird? You know you're around other people, you have to remember social moors and how to interact, and how to help and be useful.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: There's something about the freshness of ideas from students, the buoyancy, the questions, the vulnerability, the spaces that we can create, I think that keeps me from becoming hardened by my own thoughts or deepening into my own queries. It allows me to have a suppleness of mind and spirit, and the access to compassion and humanity through interfacing with students that are coming from all these different walks of life. And that are contributing these really interesting thoughts. They're really beautiful and they don't preclude a type of honesty. And so, to have that sort of thing around me, also keeps my will to be curious alive.

Alex Chambers: Do you think you could potentially lose a kind of honesty, yourself?

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Yeah, absolutely, absolutely. If I was not talking to people around me, I could lose that honesty. If I was not engaging with the writing of others or art of others, I could lose that honesty. Like if I was to myself I could lose that honesty because maybe I become so introspective, that I gain a type of honesty on the inside that I'm afraid of sharing. Or I just lose a type of access to myself. And, I'm just thinking about who I was during the pandemic, that we're still in, so the beginning of the pandemic, and think about that sort of honesty that was so feral and bewildering. And it was something that I had not experience before in that type of isolation. But also how I was grounded and availed to maintaining a type of vulnerability by speaking with those around me.

Alex Chambers: That you've been able to maintain through teaching and being in community?

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Yes, during the pandemic, I was think about that time. I think also now to parallel that, I think that the students keep me honest, they ask good questions and I think their models of honesty, are inspiring to me.

Alex Chambers: Well, I'm curious, is that honesty like a kind of vulnerability or is that a quality of it, or is it a kind of desire or willingness to communicate in a way that a poem could turn in on itself and our writing could just become writing solely for ourself?

Yalie Saweda Kamara: I think it is a type of vulnerability and I think students can weigh this out really quickly. The vulnerability versus, What do I have to lose, or what will I lose if I keep this to myself? And, I think that they're very quick at doing that in ways that I marvel at. And, I think what often wins out is the vulnerability.

Alex Chambers: And, is that a good thing?

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Absolutely.

Alex Chambers: Okay. I mean, because I think there's a tension there too. Just to keep going with various tensions, especially when we're thinking about trying to create something that's gonna be meaningful for other people. The tension between wanting to communicate something in a way that's meaningful versus just throwing everything out there and saying everything. In a way I think that maybe social media sometimes encroaches also. Does that make sense, a formlessness?

Yalie Saweda Kamara: I mean does it have to make sense to other people, is that the imperative of writing? I don't know if that is? Yeah. I don't know if that's what I'm seeking out in a creative writing class? I would hope that my students feel that they're better readers and that they can trust their aesthetic sensibilities and their impulses. And I think that vulnerability does have a value in workshops settings that I like to be a part of. There is a type of respect and caring for each other, and hearing each other and holding each other. And so, I do think that one the one level, like being able to speak and feel vulnerable, and comfortable is one thing. And, I think having people see you and hear you, even if they don't agree with you, just hear you and see you. That spirit can carry into your writing, and, what you feel and you can, and cannot write. And the boundaries that you push within yourself. And, I think if that happens at any point in their creative writing space, whether over a semester, over an hour, over a week, that's a feat.

Alex Chambers: I feel like there's also a lot of really beautiful vulnerability in the book. And, it really comes across.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: I forgot that's what we're here for.

Alex Chambers: We're supposed to be talking about the book Yalie, we're launching the book.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Yes.

Alex Chambers: This is all great, but I would also love to talk about the book because there's so much there as well. And I want to you to read every poem. Okay, maybe we can choose between two poems, maybe you can help me choose where to go? Besaydoo, I was interested in hearing, because I think it opens up thinking about the title, thinking about your relationship with your mother. And, also the questions about language and Americanness. But then also Elegy for My Two-Step, feels like it gets at something we were just talking about. I'm guessing it feels like it was written in a time of solitude? I'm really curious to hear about both of them? We could eventually do both of them, but are you leaning one way or the other?

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Yeah, I think because I'm already on Besaydoo, maybe that's where it's at? Besaydoo. While sipping coffee in mother's Toyota, we hear the bird call of two teenage boys in the parking lot. "I", one says, "Besaydoo", the other returns as they reach for each other. Their cupped handshake pops like the first firecrackers of summer, their fingers shimmy as if they're solving a Rubik's Cube just beyond our sight. Moments later their Schwinns head in opposite directions. My mother turns to me, revealing the milky John Walters mustache thin foam on her upper lip, "What's it them been saying, Besaydoo, that English?" she asks. Tickled by this tangle of new language, "All right, be safe dude", I pull apart each syllable like string cheese for her. "Oh yeah, them now go party", she smiles.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Surprisingly broken by the tenderness expressed by what half my family might call, "thugs". "Besaydoo, Besaydoo, Besaydoo", we chirp in the car, then, nightly into our phones after I leave California. "Besaydoo" she says, as she softly muffles the rattling of my bones in new found sobriety. "Besaydoo" I say years later, her response made raspy by an oxygen treatment at the ER. "Besaydoo" we whisper to each other across the country, like some word from deep in the sun where two newborn show off for the outdoors. But we saw those two boys do it, in broad daylight, under a decadent ruinous sun. "Besaydoo, Besaydoo, Besaydoo", we say, "Besaydoo" and split one more for the road. For all the struggle, tumble, drown, "Besaydoo" we say to get on the good foot. We get off of the phone, tight like the bulbous air of two palms that have just kissed. Kissed.

Alex Chambers: Thank you. It's so great, there's so much in the book that's about things that are really hard. And, there's a lot of really strong feeling and sincerity. And, this poem acknowledges some hardness, but there's also like this playfulness to it. The cheekiness in the phrase, "Besaydoo", "Be safe dude" and that's what bubbles out of that. What made it feel like the right thing to be the title poem of the book?

Yalie Saweda Kamara: I don't get asked this question enough, I love this. So, the title of the book, which was my Thesis title originally, was "Loud Organs and Extraordinary Horns." And, that felt like the spirit of the book and I'd just written this poem in, I wanna say July of 2019? And, Ross Gay did a reading in Cincinnati in, I wanna say October of 2019. And, he and our friends, Kate, and Stephanie were with me while I was doing writing workshops at Wordplay. And, I read the poem to them, before I entered the space, just to share some new work with them. everything kind of locked in place for me. And, I realized that the title before was a placeholder for the spirit of the collection and "Besaydoo" was the actual name of it.

And, a few days later I sent Ross the poem and he said, "That would make an excellent book title?" And, I back spaced, "Loud Organs and Extraordinary Horns" and I typed in "Besaydoo". And, I was like, "Whoa" everything kind of locked in place for me. And, I realized that the title before was a placeholder for the spirit of the collection and "Besaydoo" was the actual name of it. And, I think that the spirit of the original title was completely embodied in the phrase "Besaydoo", and so that's how the title came about.

Alex Chambers: Oh that's great.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Yeah. I don't even know if Ross remembers that he did that, but it changed everything in the book.

Alex Chambers: Did it feel like it changed the book overall too?

Yalie Saweda Kamara: It didn't feel like it changed the book overall, but I will say, it gave me that last little push to finish the book. It got me really excited about finishing the book.

Alex Chambers: And, it's so interesting just as a phrase, because it's not clear what it means, until you read the poem of course.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Yeah, absolutely. Whilst on a Zoom call with some older women, I'd left the volume up and they're like, "Besaydoo", something from Sierra Leone, is that something from a dialect? And, another older lady was like, "No, read the poem?" I really appreciate how things carry sort of sonically from the word on the page and just how people find their way to it. And, what's been awesome about that, is, it's been cool to hear people say, "Besaydoo" and tell me that they share it with their loved ones. And, it also creates this form where other people share their family words. And, so it's been really cool to hear about this kind of word and just to be in the center of constellation of shared and created language that pulls closer.

Alex Chambers: It's time for break? I'm talking with the poet, Yalie Saweda Kamara. Her first full-length collection, "Besaydoo" came out in January. When we come back, we'll hear another poem and talk about how Yalie's life has changed in, and because of the Midwest. Stick around?

Alex Chambers: It's Inner States. I'm Alex Chambers. I'm talking with poet, Yalie Saweda Kamara. Let's get right back to it.

Alex Chambers: I do want to talk about place a bit. My show, Inner States is partly thinking about place in the Midwest and what it means to be here. You are from Oakland. Did you move to the Midwest originally, to Bloomington, for your MFA?

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Yes.

Alex Chambers: And you have a few poems about Bloomington and some wonderful poems about Oakland. I was thinking about LRG for my two-step, potentially as one to use to think about place as well. The other one I was thinking about was the more prosy one where you're describing meeting a pastor. And the pastor commenting on where that person is from as a dangerous place.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Oh, that poem. That is [PHONETIC: Eloctrocus], I think.

Alex Chambers: Yes.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Yes. I will try hard to read it. I'll be careful. It's just with the spacing like this, it takes some time now. You know, it's part of the poem?

Alex Chambers: Oh, I did not think about that.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: No, it's three pages.

Alex Chambers: It's three pages, right. That totally makes sense. I read it along and it felt like a continuation. But I did not think about it as actually being.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: I'll give it a go. [LAUGHS]

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS]

Yalie Saweda Kamara: I'll give it a go.

Alex Chambers: I think it will be fun to see how it unfolds.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Fun for you. [LAUGHS]

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS]

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Okay. Eloctrocus. "After the service in the auditorium, the congregation lines up to greet the pastor as if he himself were a second coming. Every man is joined to his wife, who is joined to a bonnet, who is joined to a bun and a bundle of babies. When it's the guest's turn, he cannot control himself. 'Your hair is like Angela Davis's or Colin Kaeperknick's.' 'Well, which is it?', he asks as if to quiz her. She smiles instead, taking neither option. Eloctrocus, that's what they call your hair. It means woolly, big. She thanks him for the word, for what she knows will be the only gift she will receive. 'Where are you from?' She responds. 'Wow, that's tough', he says, not realizing that you grip seeing more and never witnessed.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: It reminds me of growing up in Chicago. My family used to take a couple of kids out of the Robert Taylor Homes every summer to go swimming. It used to be scary walking through those project courtyards. Real scary. Scary, she thinks, as she imagines the boys running back to their hell after an afternoon in his. 'Bloomington must be hard. Not a good place for people like you.' She retorts, countering his assumption. But providence, she thinks. She thinks she says, 'But God', she says. 'But God', she says, 'it's swell. I am well. It is good. I am, I am, I am the one who has gone. Fine, I'm going, going to go. I am gone. Going to leave now. You. I am going to leave. You cannot really hear me screaming now. Leave my hair. Me, gone, gone, disappear, goodbye. It's fine. I am screaming disappear. Well, I am going now. I am going, going to leave. Well, I am the one going to leave my hair. It is I who has to go leave now. You, me, good. You cannot. I am, am gone. I am gone. Really, hear me. Gone, gone, goodbye'."

Alex Chambers: Formally, I should say, that last section that feels repeated is quite spread out on the page and you read it across and then down in columns.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Yes.

Alex Chambers: Which I didn't think to read it that way when I was reading the book to myself.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Well this is the power of community that we've been talking about.

Alex Chambers: Exactly. Yes. The different ways. And not just hearing this through conversation but just opening up the different ways you can encounter a poem and think about how it works. So what I was curious to ask was how did moving to the Midwest change how you thought about either the country or yourself?

Yalie Saweda Kamara: So I think living in the Midwest, a couple of things. Well actually, a lot of things have happened. I think moving to the Midwest changed my life in the sense that it saved my life in a lot of ways. So a lot about the Midwest. I think one thing is thinking about encountering community in a really beautiful way in the Bay area and then seeing a whole other way of thinking about community in the Midwest. I've never been to community orchard before. I never have participated in writing workshops that took place both on campus and a writing workshop that had nothing to do with campus. The possibility of those things existing, or going to another place where you can do a little bit of farm labor and have food to last you for a very long time. When you think about it, the point really isn't the labor, it's to give you food.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: I got baptized actually in Bloomington. Not actually, of course, it happened in the Midwest. And being able to walk to a place of worship and to be able to know that that's just not too far outside of my door was something that was really important to me. All these different ways of people filling you up with a type of love and care, artistically and spiritually. Something that was different and maybe it's also part of the community. The feeling of being able to walk to things in a way that, spatially it's a different place. To be able to look and see sample gates from a particular part of town and be, like, I can walk to work whereas, living in California, I was in commute about 25 hours a week. So, being able to walk 15 minutes. All these things change how you see the possibility of our own time. I did find ways of using my time; that commute time was spent writing applications, completing applications, personal statements, and getting writing samples together. I made use of that time but it's different when you can use your time in a way that is maybe more yours.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: What else about the Midwest? There's a type of quality of life that I think I've encountered here that, as a grad student in maybe other regions of America, I would not be able to have. So, there is something very special about that. Even now, I feel like the place where I live I would have to have 86 room mates in the Bay area. So there's something really cool about space to be by oneself, in a way.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: I will say that the speed of the Midwest has been something that has allowed me to have greater access to my thoughts, and I would say, tied to that, is maybe hearing in a different way. Part of that, I think, is tied to thinking about particular choices in my life that show up in the collection and thinking about sobriety. Maybe that slowness of life allowed me to think about how my life could be better without certain influences and certain people. I think those sorts of thing happen with pace, and with a type of isolation that I encountered in the Midwest. I don't mean it is an exiled way, but in a way that I just was able to turn in a little bit more to myself.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: I think those are some of the changes that I encountered. I feel like I've talked so much. How has it changed me? I feel a deeper sense of spirituality and gratitude, I think, living here. It would be interesting to see what would happen if, what has the Midwest activated in me, I can take to other places. I think they're more loving. I think that's what happened, living in the Midwest. I think I've gotten more loving. I'm still snobby in some ways.

Alex Chambers: Good for you. Hold onto that too.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Yes. I'm going to hold onto that.

Alex Chambers: Yes.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: It's righteous snobbiness. I've encountered these incredibly creative acts of love that have taught me how to be a fuller human. I think part of that is maybe age too, but I definitely believe that a lot of it has to do with living in the Midwest.

Alex Chambers: And that's been the case also in Cincinnati which is, of course, a bigger city than Bloomington. Is that the case?

Yalie Saweda Kamara: It is. I walk quicker. When I moved from Bloomington, which kind of followed Polly Pocket, just kind of booping and bopping all over town. I realized I was walking quite slow, and I was sauntering, I was moseying, so I had to pick up the pace a little bit in Cincinnati. But it has been an incredibly kind city to me, and it's a city where there is a welcoming of artistic innovation and collaboration. That even was kind of how this Blink project came to be was someone believed in an idea that I had, and I was able to take off with it and so I've been really grateful to be in a city too that is excited about the arts as well. I think a lot of that training, and that thinking about art in this sort of human and collaborative way too, I will absolutely credit Bloomington for having a part of that. So I think that is a really blessed order of things, to have moved from Bloomington to Cincinnati. I feel grateful to not be so far from Bloomington ever. I don't think that's something that I necessarily understood. I didn't understand it, when I first moved from California, what Bloomington would eventually mean to me.

Alex Chambers: That's really cool, and interesting to hear about the kind of healing that being in a place like this allowed, that then maybe came through and helped you develop further in your writing as well.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Absolutely. I found my writing voice in Bloomington. I found God and my writing voice in Bloomington. I had some ideas, and a lot more questions before I moved to the Midwest. Yes, it's such an unexpected thing. To get off of a plane with my Mom and say, "Mom, did you think that when you moved to America that you'd ever end up walking through Bloomington, Indiana with your daughter?" Just having these thoughts. What is going on? And that's the surprise. Just the gift of life. Just things you don't expect to happen. I did not expect any of these things to happen to me when I moved to Bloomington, or to the Midwest in general.

Alex Chambers: You say you found God and your writing voice in Bloomington. Can you say more about that?

Yalie Saweda Kamara: I can read you a poem about it.

Alex Chambers: Please. Even better.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Yes, I'll read you Bloomington, Indiana, part one. I think that encapsulates the whole thing.

Alex Chambers: Page 40.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Bloomington, Indiana, part one. "Before I learn to die unto myself, I am told by a pastor who I had just met, when visiting an Aunt who I had only previously spoken to on the phone, that my life could kill me. 'The way I hold myself,' he says, 'between the pinch of the index finger and thumb is simply not enough.' I tussle with the warning, then let it ring in the middle of my ear for a week before I begin to empty myself of myself. I've never been told this by a stranger, but think I agree. I believe I could be slowly dying, particularly when thinking of every morning after every evening that started out as an escape. I say farewell to the comforts of Indiana that make the move from the Bay area feel easy. These comforts are so cheap that they appear exotic. Goodbye, $3 shots and $2 pints. I exhale the last American spirit and clean the final bullet wound. I let go of my acquaintance with Bio. I upchuck the garnet and bubble gut the amber of Midwestern excess. I think being around friends who still partake in the life that is not good for me will have no effect, but in their presence I feel the urge to back step. A strange, loud booming heart-racing anxiety gnaws at me from the inside. This ugly sensation is the beginning of a lifestyle change. I erase Tinder, but before I do, I stare long at the handsome man who pins down an antlered creature in his profile pick. In real life, I scrub all the John Deer from the poor, and the membrane, and the bed sheet. There's so much on which to swipe left in my own life. This business of being careful is heavy. I commit tentatively. I stay away from bars as often as I can, which means missing out on some MFA events.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: I skip parties too. Though I stop drinking, I leave a bottle of Cardinal Vodka in my fridge for a month before throwing it out. Though I become celibate, I don't erase the numbers of my favorites. Nothing is completely immediate. There is an ever so slight feeling of safety in the thought of returning to the ritual of toxic behavior. I don't know know what is possible in my own life, thought I want to be a writer and wish to be more centered. The difficulty here is I don't understand the extent of wishing and hoping, or the far reaches of dreaming. I keep being told that permanent change cannot be made in private. I don't understand that fully either, but want to hear from others. For the first time in my life, I begin to go to church, not before saying no to many. The church where the music sounds distorted, the one where the pastor-in-training leaves hands on my head to perform a holiness I cannot feel. The one with the delicious communion bread and banjos, but is far too quiet for my West African sensibilities. I join a Baptist church where they shout and cry, where everyone is broken but trying. The one in which honest sinners are happy to hold my hand and double squeeze my knuckle at the end of prayer. Mercy.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: I like that the church is walking distance from my home, but feel worried about a tax on black congregations. One of the parishioners is a Sheriff. He makes sure to always park his squad car in front of the church. He prays and sings mellifluously throughout every service. My stomach knots after the first time I see it. When he turns to put ties in the collection plate, the motion reveals his holstered gun. This is an open carry state, even in the sanctuary. Community helps. Time helps too, but really solitude deserves more credit in the conversation on healing. I become more able to steer clear of my ennui and my ratchet. I go to the library to study line bricks by myself. I tell my friend it's about to get weird, then lose most of them. Glory, I find my favorite places to hide. One of them is in my kitchen. Something about the space gets me. It is small and tucked away, like my life here. While it is a place to cook, it is also a place to cry, to arc, to bend, to break, to come back together with no human watching.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: I sooth with the book of John, Psalms, Pamplemousse, Lacroix, vegan apple cider donuts, new wigs, podcasts. My mouth ever agape, agape, embouchure. After a season I, aqueous, unravel in the waters of baptism. After I dry, what stained glass is still trickling from my ear? I find a metaphor in this. Something about praise being messy. Most things are bright, and the sound is loud. This is a type of rising from sleep. All of this in Bloomington, Indiana. What I knew but did not want to know was that a friend was called the monkey and spat on around the corner from my apartment. What I remembered, but did not want to remember, was the car with the tinted windows that once followed me for blocks. What I recall, but want to forget, is why we never stopped for gas in Martinsville.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: What doesn't surprise me is that neo-Nazis saw fresh produce at the farmers market. And I'm certain the blood never dries in Indiana. I'm also certain that the blood never loses it's power. This is where I found my God, nodding me awake. [FOREIGN DIALOGUE] "

Alex Chambers: One of the things I appreciate about the poem is there are so many kind of moments of finding presence in this place. It's funny because I have read it a couple of times but, still, as we got to the end, I was, like, "Oh, this place is sounding so wonderful, beautiful, and just perfect." Then we are reminded that it's also got its own messes as well.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Yes.

Alex Chambers: Just that third to last line, "I am certain the blood never dries in Indiana. I am also certain that the blood never loses its power". It feels like that is a line that is resonant, in some ways for the book as a whole too, in the sense that there is an awareness certainly of violence throughout some of the poems. As I have mentioned a couple of times, also a fair amount of loss, and that that sadness and hurt is something that we all have to be with, but that it also gives us something I think too.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Thank you for that. And it's from trying to go to church, and going to a Baptist church. And this is one of the Gospel songs. Some lines from that, and thinking about the majesty of the Almighty and how it flows to all these different places. How there's an ever-lasting presence in faith. So thinking about that as this sort of divine imagery, but also the very real brutality of blood never drying in America, in perhaps the most American part of America. At least in the top three most American parts of America. That is this sort of twinned legacy, both on Earth as it is in heaven, which is really interesting to walk through, thinking along the lines of race and faith in this century.

Alex Chambers: Alright, let's take another break. I'm talking with poet, Yalie Saweda Kamara. She's the Cincinnati and Mercantile Library Poet Laureate. In her poetry collection Besaydoo came out in January. When we come back, we'll talk about Andy X, a family member who makes multiple appearances in the book, at one point hiding from immigration agents in a hospital morgue. Stay with us.

Alex Chambers: Welcome back to Inner States. I'm Alex Chambers. I'm talking with Yalie Saweda Kamara about her debut poetry collection Besaydoo. Among other things, the book is about what we can learn from the people who came before us, especially our own ancestors, and how we can take care of each other. I think the cover gets at that. It's a rich, golden yellow, and there are two hands reaching up into the air, maybe giving each other a high-five, maybe about to clasp each other in love, or support.

Alex Chambers: I would love to hear about Aunty X.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: [LAUGHS]

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS]. She's such an interesting, fascinating character in the book. She comes in with that wonderful poem which is kind of a story too, about her being in the hospital, and having something in the 1980's, so I don't know if it was Immigration and Customs Enforcement calling her, if that was the organization then, but, guess it was. And, I feel like she's kind of saucy. But then, also, at the end of the book, there's this really heartbreaking poem, thinking about the loss of her son. I don't know that I have a good question. I would just love to hear about what she means for the book. And something I'm thinking is, what it means to be keeping stories alive for family members who are still here, as well as those who are gone.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Yes. So, Aunty X is, Aunty X by virtue of the enormity of her life, and I don't know who else would see Aunty X in this way, I just don't know anybody around me that would think of Aunty X as human and also, almost a myth. Thinking about the sort of grandeur and the expansiveness of her life. She's someone who I know has not been told how huge her life is, or has not been dignified in a way that her stories are kept.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Just being in her presence and growing up with her, I've just become increasingly fascinated by her as one of the first women in my life that I thought was so cool. She has a faded tattoo, from like, life in Sierra Leone. I don't even know what it says. The first time I saw the tattoo, I was like, "Wow," you know?

Alex Chambers: Yeah.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: I didn't know a Sierra Leonean women could have tattoos. [LAUGHS] And, kind of thinking about the ways that she tells stories in this nonchalant way, and the ways that she talks about life, and her voice never ever changes. It's always the same sort of, sweet and placid sort of tone, and she's telling you these things, where you have to kind of, lean in to listen to the rise and the fall of the story. And there's a casual laugh here and there, but I'm like, "Wow, this is a story that is about people becoming invisible."

Yalie Saweda Kamara: In the poem where my mother says, "Don't Repeat This to--" I think that's the title of the poem, or something along those lines. That's not responsible of me, let me tell you what the actual title of the poem is. [LAUGHS] " Because My Mother Says Don't repeat This, you Must Know," and just thinking about that line, or that poem, and that story, and how she essentially disappears, or becomes invisible in some ways. And then, by the end of the book--

Alex Chambers: Just for listeners, that's because she's been working in this hospital, and she's an immigrant.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Right. And there are questions around her status, her immigration status. And so, what happens when a group of people collaborates to disappear someone in the interests of their survival. And then, the reappearance of Aunty X near the end of the book, in which she's in grief, and dealing with the loss of her son by suicide, and thinking about disappearances in that way and reappearances through love, and what reconciliation or healing can do to resurface someone who has been lost.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: And so, thinking about that, and thinking about cultural practices that help bring that to the fore, is something that I was interested in too. Actually that poem started off as a creative, non-fiction piece and that didn't become.

Alex Chambers: The last poem, or the poem "Because My Mother Says Don't Repeat This."?

Yalie Saweda Kamara: The last poem. I'm continuing to talk about Aunty X from moving from there to the last few poem, "Aunty X's Dream Door Has" and then Aunty X in the final poem.

Alex Chambers: Right, the one that's considering about the grief about her son, who then comes back as a spirit around the table.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Right. Absolutely. And so, thinking about that, it was important for me to think about the poem ending in light and the book ending in light. The first poem-- Is this the first poem? Give me a second. I'm just figuring out the anatomy of my own book. Yes, the first poem, "Oakland as Home, Home as Myth." The final line in that poem is, "The object that casts the biggest shadows are the one closest to the light." And the final line of the final poem is also considering light, and it's Aunty X thanking God for not leaving her in the dark.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: It was important for me to end off the book in a type of light, and thinking about Aunty X, and other people that show up in this collection, some have stories and they have been profound in their ways that bring kind of a particular attention to who they are. There are other people who are sort of, unsung heroes and I'm invested in bringing that story to a greater audience.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: There are all sorts of things we can learn from people that we don't necessarily position as our teachers. I also think that sort of spirit of like, not giving a voice to the voiceless, that's yucky, but I'm talking about amplifying voices. My grandmother and my mother are incredible story tellers. I'm not smarter than they are, I just have had particular opportunities that they didn't have. So, thinking about the sort of richness of the people in the worlds that I come from, and just wanting to celebrate that, I think is what I'm trying to do with these poems.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: And yes, this is a hard thing to celebrate, or talk about, loss of life, but it's important to celebrate who people are, and who people become, and who people were before they were struck by a type of tragedy. And so, this book is also thinking about overall, what have we overcome, and what do we share in our overcoming with others, as a way of engaging that spirit and them igniting that will to continue and will to thrive within them.

Alex Chambers: And so much of that has to do, I think, with community and being with others.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Yes. And the hands, absolutely in the hands.

Alex Chambers: And just put the hands together?

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Yes. Thinking about Sierra Leonean proverb at the beginning, "Han Go, Han Kam." I'll actually read that. So, start at the very beginning of the book, and thinking about the hands. I want to give a shout out to the graphic designer at Milkweed, Mary Austin Speaker, who is a graduate of IE's MFA Creative Writing Program. She's a poet and a brilliant graphic designer. I'm just grateful to Milkweed in general for all this amazing work

Yalie Saweda Kamara: The Sierra Leonean Krio proverb is "Han Go, Han Kam," and if you were to translate it literally, your "hand goes, hand comes," which means, "the helping hand that leaves in love returns in loyalty." So, there's always a return, and there's always this sort of, in order to move forward, we have to always be looking behind us and to the sides of us. And there is a responsibility and an honor in doing that.

Alex Chambers: Beautiful. Thank you, Yalie. This has been really wonderful.

Yalie Saweda Kamara: Thank you. It's been great.

Alex Chambers: That's it for the show. You've been listening to Inner States from WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana. If you have a story for us, or you've got some sound we should hear, let us know at WFIU.org/innerstates. And hey, if you like the show, review and rate us on Apple or Spotify. And tell a friend. Okay, we've got your quick moment of slow radio coming up, but first, the credits.

Alex Chambers: Inner States is produced and edited by me, Alex Chambers, with Harvey Forrest. Our social media master is Jillian Blackburn. We get support from Eoban Binder, Mark Chilla, LuAnn Johnson, Sam Schemenauer, Payton Whaley, and Kayte Young. Our Executive Producer is Eric Bolstridge. Our theme song is by Amy Oelsner and Justin Vollmar. We have additional music from the artists at Universal Production Music.

Alex Chambers: All right, time for some pound sound.

Alex Chambers: That was "Walking on the Boardwalk at McCormick's Creek State Park." Until next week, I'm Alex Chambers. Thanks, as always, for listening.