Alex Chambers: Danny Cain's been fishing since he could walk. He used to run trout lines with his dad.

Danny Cain: I got taught to hustle and bait for trout lines. Buddy and I got some nets and we thought we would catch a lot of fish. We didn't catch nothing.

Alex Chambers: That didn't stop Danny though. He learned to make nets by hand and he's been net fishing now for 40 years. This week on Inner States, Danny Cain walks Violet Baron through the process of making fishing nets by hand. They also talk about invasive species like Asian carp and how they're kind of an acquired taste. Then we listen back to a 2016 interview with Peter LoPilato, founder of the Writer Film Series and Magazine. He passed away on March 7th. That's all coming up after this.

Alex Chambers: It was almost a quarter century ago that I went to this movie. It was a David Lynch film. I'd seen Blue Velvet so I had a sense of what to expect, but I wasn't really prepared. Mulholland Drive was crazy. There was this one scene in particular where the sort of death figure comes out from behind a dumpster and I jumped out of my seat. That scene is bound up with the place where I saw it. It was at Bear's Place, which was this restaurant and bar and jazz club and they did other things, just on the edge of Indiana University Campus here in Bloomington. And the whole reason I was able to see Mulholland Drive, which was this sort of weird art film that wasn't probably being shown in the AMC Theater, was because it was being shown as part of this film series here in town. If you're from here, you know what I'm talking about. It's the Ryder Film Series. When I saw Mulholland Drive at Bear's Place, probably with a beer in hand, the Ryder Series had already been going on for over 20 years. It was already a cultural institution, and that's part of what I wanna think about today in this episode is cultural institutions and what they do for a place. And I don't mean cultural institutions like the University or maybe a big church or the New Yorker Magazine or The Symphony that has a lot of money, if your town's Symphony has a lot of money.

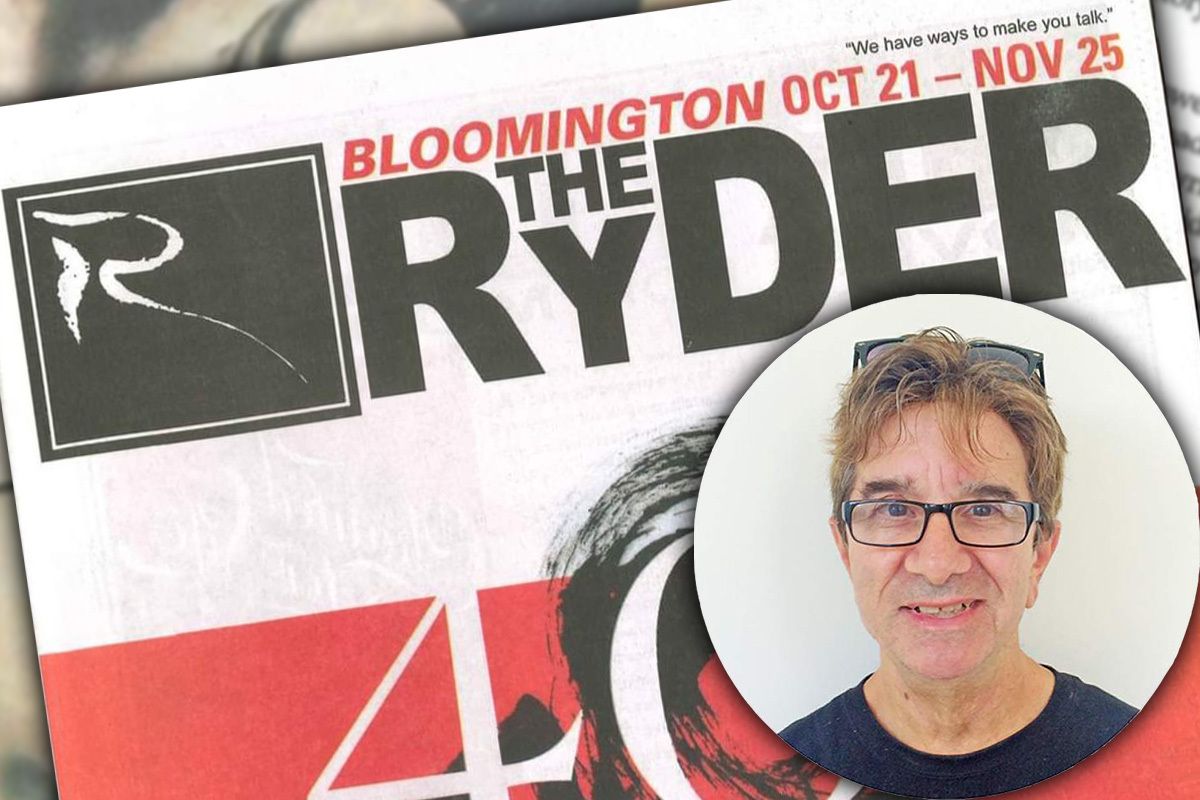

Alex Chambers: Really, I'm interested in these little sort of niche cultural institutions that end up being really important for the community. The Ryder is one of those cultural institutions in Bloomington. It's a film series that's been going on since 1979. It's also this magazine that you can pick up for free in coffee shops and elsewhere around town. It's got an events calendar and articles written by local people about local arts and culture. This most recent issue has tips for the eclipse and an article explaining the problem with building more jails and prisons and more. Anyway, the reason I'm talking about the Ryder is that its founder, Peter LoPilato, he was listed as both the alpha and the omega in the magazine's masthead, he passed away last week due to complications from some longstanding health issues. He was really beloved in the community. So, I want to replay an interview Yael Ksander did with Peter in 2016 for WFIU's profiles. They talk about how Peter put Bloomington on the national cinematic map, the wild west of Bloomington's 1970's art scene, the audible gasp when people saw Donna Reed in It's A Wonderful Life for the very first time and more.

Alex Chambers: One of the things I find most impressive about Peter is his ability to create these two institutions, the magazine and the film series, that he sustained for decades. They've both been around for over 40 years now. So, we'll listen to Yael's conversation with Peter. But first, we're gonna consider another kind of cultural institution. It's about the kinds of traditions that get passed down from one person to the next, even if sometimes it takes a grant from an institution to keep that tradition going. Producer, Violet Baron, talked with Danny Cain about making fishing nets by hand. Here's Violet.

Violet Baron: The filmmaker, Hannah Lindgren's 2022 documentary, The Net Makers, featured Danny Cain and Larry Haycroft, two fisherman who craft their own fishing nets to catch catfish in the rivers of rural Southern Indiana. The film shows the men at work fishing on small motorized boats and at home hand-tying thousands of intricate knots to make the huge hoop nets. I visited Danny at his home in New Harmony to hear more of his story.

Violet Baron: What got you into it?

Danny Cain: I've been fishing since I could walk, with my dad, and he would run trout lines, put 50 hooks on every trout line and he might put out six to eight trout lines, and once we got old enough, us kids went and got the bait. I got tired of hustling bait for trout lines and Buddy and I got some nets and we thought we were going to catch a lot of fish. We dropped them in the river, we didn't catch nothing. And Jim Cooper seen us one day and he told us that you fools, you're fishing in the wrong place and he helped us out, and I've been net fishing now for 40 something years. Jim Cooper's my mentor, he taught me to make nets, he got a grant from university to teach me and Timmy Durham how to make nets and, far as I know, we're both still making nets. I haven't talked to Tim in several years.

Violet Baron: And what was it like learning from Jim how to do it? Because if you're not used to it, it's a whole new world, right?

Danny Cain: Yeah, it's boring really. You tie one knot five or six thousand times or more. So, it's just repetition of one knot over and over and over. You got to gage your block that gives you your size of your webbing and just wrap around that, tie a knot and do that over and over and over. Then you got your take ups and all this, it's still the same knot. He gave me the nets at first and he showed me how to use them. He told me I was dumb and to get out and he said, you don't know what you're doing. He's right. He showed me where to fish and all this and I went with him to run his nets. I learned from that and after that it's trial and error.

Violet Baron: Trial and error meaning sometimes you can make those knots correctly and sometimes you have to fix them?

Danny Cain: Yeah. If you don't get the knot right, you got to untie it. If you make a mistake, I got a rule, you untie back to that mistake. My son-in-law untied 41 mesh, two knots to a mesh, I think it was 81 around, to correct a mistake. He did not make that mistake again. So you learn. I still make mistakes but I can tie my way out of them now. We buy the webbing in a sheet, buy it by the pound and we cut it out, he showed me how to cut out what I needed, how to tie it together and how to start my throats. I can tie knots while I'm talking to you right here. I've done so many of them, my hands know what to do, I don't, my hands do. I just keep going round and round and round. Sit here, watch TV, talk to my wife.

Violet Baron: Yeah, you got a nice big screen propped against the wall, so you got it all set up here. Plus you've got a glove, does it rip up your hands after a while?

Danny Cain: Yes it does. And this glove will make about three nets.

Violet Baron: Oh, before it gets all ripped up?

Danny Cain: Yeah. I sit here like this.

Violet Baron: Yanking it tight.

Danny Cain: Yes, that is tight. I'm doing a take up right now and I'm making sure I'm doing it right because I don't want to untie it. Now, here's where we come up to the pig string.

Violet Baron: Did you say pig string?

Danny Cain: Yes.

Violet Baron: What's that?

Danny Cain: It's the name Cooper gave it. [LAUGHS] Just a string that hangs down.

Violet Baron: Oh, I see that other dangling shuttle, yeah.

Danny Cain: That's what this is.

Violet Baron: I'm worried you're going to call me in two weeks and say, you know what, I made a mistake while we were together, now I have to start over. But you've been doing this a long time.

Danny Cain: Over 30 years. You can see here on this net where I pull the string on the glove, it's starting to wear right there and I just bought this glove. If you know anybody that only needs a left hand glove, I got a bunch of them.

Danny Cain: It's a losing proposition. I've sold maybe six or seven nets in my life because people come up and they want five or six nets, today. It would take me a year to make five or six nets in my spare time. But they can call this net company, tell them what they want and they'd ship them out tomorrow.

Violet Baron: But selling the fish that you catch in those nets, is that the main business for you or it has been?

Danny Cain: It has been in the past, yes, but not anymore. The Asian carp are killing off all the little fish. I keep the buffalo and the catfish.

Violet Baron: The Asian carp are crowding them out now?

Danny Cain: They're starving them out. Asian carp lives off of plankton, it's a little micro organism that all baby fish need. If you don't have babies, you don't have adults. There's no predator for them. Nothing eats the minnows. There's no predator, nothing to slow them down. No I've ate it and it's a better tasting fish than the catfish.

Violet Baron: But it's very bony, right, it's difficult to skin?

Danny Cain: Yes, they're very difficult. There's a spot in there where you can get the fillet out of it. I just got to find this and how to get it out.

Violet Baron: And so, if you're learning this year how to do it then that might be a change for you, right?

Danny Cain: Yeah, I'd be fishing for them, leave what catfish out there.

Danny Cain: When I get done, and I've done it right, it's a beautiful net. I have actually hung them up in the front yard and my son thought I had a Christmas tree in my front yard. And he said, Dad doesn't have a tree there. Hung a net up and put lights on it. Everybody thinks you've got a Christmas tree.

Violet Baron: What was that like for you being part of The Net Makers documentary?

Danny Cain: I was real interested in that and I enjoyed doing it. Sometimes it's hard to explain to someone who doesn't know what I'm doing. Like, I tell you I fillet the fish, you don't know what I'm talking about. What I'm doing, I'm cutting the meat off the bone, and then it's got a red meat on the outside of it, we cut this off, makes a better tasting meat. We went out on the river and showed them how it was done, showed them the Asian carp, soon as they jump in the boat, they start bleeding. They see enough of them in a heartbeat. After we got through running nets on the river, we came back and I cooked fish for everybody but Hannah, she's a vegetarian, she don't eat fish. Didn't bother us, we ate the fish.

Violet Baron: You mentioned that you did do an apprenticeship, right, where you taught someone how to do that, was that your son-in-law or someone else?

Danny Cain: My son-in-law and my nephew both.

Violet Baron: Did it remind you of when you were learning?

Danny Cain: Yes.

Violet Baron: Were they different at all? Is this generation a little less patient?

Danny Cain: They're both still making nets. My son-in-law tied his totally and he told me, when he finishes this net, he's going to order webbing. He said, I'm tired of tying them. The way he works, he can't fish. He works four days, 12 hours.

Violet Baron: Sounds like long hours. Doesn't give you a lot of free time to be out on the water, right?

Danny Cain: Yeah, because by law you have to run them every 48 hours. In the summertime, water's hot, you have to run them every 48 hours or you'd lose all your fish, they'd die. This time of year, you could actually get by running once a week and the fish would still be alive, still be in good shape. Fish are like you and I, they're not going out here in the middle of the stream, walking against the wind or what have you, you just go over here where it's something blocking it a little bit, taking it easy. It gets hot, they want to be cool, so they go deep. And when it gets cold, they come up. There's a warm layer in there.

Violet Baron: And is anybody you know learning right now, in the process of learning as a new student?

Danny Cain: No, I'm looking.

Violet Baron: Yeah.

Danny Cain: My other son-in-law, he said he knows some guys that might be interested but he hasn't got back to me yet.

Violet Baron: Do you think it's going to continue, this craft?

Danny Cain: No, not unless we find a way to eat the Asian carp, and when you say carp, 90% of the people, I ain't eating that.

Violet Baron: Because it's so hard to fillet?

Danny Cain: It's got so many bones in it, we're too lazy to pick around them.

Violet Baron: Do you think we could learn?

Danny Cain: Yeah, I've ate them.

Violet Baron: And you said the meat's actually good.

Danny Cain: Yeah. I've ate the Asian carp. Guy over Graysville took over the fish market after John Farmer died and he was cooking Asian carp, three of us went over to try it and we all got our catfish and our other stuff and one or two pieces of Asian carp and we went back for seconds, we didn't get any catfish, we got Asian carp.

Violet Baron: Interesting. Do you think that there can be a process to make the filleting part easier because they're so bony?

Danny Cain: I don't know. I'm a find out.

Danny Cain: This is a finished net.

Violet Baron: It's beautiful.

Danny Cain: Yeah. There's a whole lot of knots on the outside.

Violet Baron: It's a white net with green hoops keeping the shape and it's got sort of two layers of net funnels inside it.

Danny Cain: Yeah, two funnels.

Violet Baron: So, it guides the fish in and then it's very hard for them to get out of there.

Danny Cain: Yeah, your first goal is a starter, all it does is start the fish up in the net and your second one is a keeper. Once they get in they can't get out.

Violet Baron: Yeah, looks like a keeper. It's a fish motel.

Danny Cain: Yeah. Now those two hanging on the wall there are six foot.

Violet Baron: And they're darker, they look a little older. Are they older?

Danny Cain: They are. I don't fish them anymore. I can't fish them anymore. I'm not strong enough anymore to work them and all this.

Violet Baron: But I guess they would get a good yield, right?

Danny Cain: Last time I had it out, had 358 pound of buffalo in it.

Violet Baron: Wow. And buffalo's a kind of fish?

Danny Cain: Yeah.

Violet Baron: And that's a black color?

Danny Cain: You put some tar on them that preserves them in the water. Makes it easier to clean the trash off and the fish don't get tangled up in it as quick. This preserves the string. You put nylon string out in the sunlight and it deteriorates quickly.

Violet Baron: Okay, so this keeps it strong.

Violet Baron: There was a funny moment in that presentation when you and Larry were talking about the cheese that you use.

Danny Cain: Yeah.

Violet Baron: Do you mind just telling about that cheese?

Danny Cain: Okay, the cheese I have, scrap cheese from the cheese factories, okay. Been sitting out there in my barn in a barrel for about three years.

Violet Baron: Yum!

Danny Cain: That's not the word for it. We bait it with our hands, we don't wear gloves, and it stinks. It doesn't come off your hands unless you use toothpaste. Anything that stinks. The more stinks the more they like it. Now this was the cheese.

Violet Baron: Oh, wow.

Danny Cain: And you smell it already, don't you?

Violet Baron: I do. Doesn't look like food. Wow.

Danny Cain: I've put cheap dog food in it to soak up the water.

Violet Baron: I see.

Danny Cain: I got cheese in this barrel, that barrel and this one.

Violet Baron: Yeah, so you've got three plastic barrels and it just looks like brown sludge.

Danny Cain: I used liver one time. The reason I say one time, when I brought it up off the bottom of the river after being out there for two days, I almost lost my lunch. And I had to dump this stuff out of a bag. But I caught fish.

Danny Cain: Used to, when I was fishing, I'm a say 30 years ago, I knew about eight commercial fishermen in this area. I know two now.

Violet Baron: Right, people are just moving away from it. They're doing something else.

Danny Cain: We're dying off. Most of them have died off.

Violet Baron: And new people didn't take it on.

Danny Cain: Young people ain't interested in it. I don't sell fish to anybody under 40 years old.

Violet Baron: They buy it at the market or something.

Danny Cain: Yeah, and if they knew what they was eating they wouldn't buy it. It's Swai, comes from Vietnam.

Violet Baron: Why do you think they're doing that though? Convenience?

Danny Cain: Convenience and ease. I mean, I can go to Farmboy, buy a box of fish fillets, I'm a say three or four dollars a pound, I really don't know, and fry them up and some people like that. I don't eat them.

Alex Chambers: Danny Cain, net maker, in conversation with producer, Violet Baron. If you want to get a visual sense of the process, check out the film, The Net Markers by Hannah Lindgren. Alright, it's time for a break. When we come back we'll listen to Yael Ksander's conversation with Peter LoPilato. Peter was the alpha and omega of the Ryder Film Series and Magazine here in Bloomington, he passed away on March 7th.

Alex Chambers: Welcome back to Inner States. Let's get right into Yael Ksander's conversation with Peter LoPilato, recorded in 2016.

Yael Ksander: It's an honor to have you in the studio today, Peter.

Peter LoPilato: It's a pleasure to be here.

Yael Ksander: So, last summer, a piece in the LA Times lamented that a certain French film that had done well Cannes Film Festival never made it to Los Angeles, but it had been screened in Bloomington, Indiana for a week and the writer wrote, with typical coastal elitism, I might add, "It's long been known that the art-house scene in Los Angeles lags behind that of New York, but must we be outdone by Iowa City and Bloomington as well?" So, I was proud to read that we had outdone Los Angeles, cinematically, and I also wondered whether you had in fact been the one to show the film.

Peter LoPilato: Oh yeah. Sure. The film is a three-hour French film called Li'l Quinquin and we showed it for... We did six screenings.

Yael Ksander: Well bravo. I think this is a great opportunity to reflect on your role in terms of the cultural evolution of Bloomington. How did you choose the film and how, in general, do you go about choosing your films?

Peter LoPilato: I get screeners. Now everything is digital there are secure websites, they send me passwords and films that are playing at festivals or films that are opening in New York, or occasionally Los Angeles. I can watch online perhaps a week or two before they open. I used to go to New York City and I would just to the theaters and see as many films as I possibly could in the ten days or so that I would be there. But now with chauffeuring around two kids it's a little bit easier to just watch them online.

Yael Ksander: Did you see that mentioned in the LA Times? Or did someone point it out to you.

Peter LoPilato: A couple of people sent it to me.

Yael Ksander: What was your first response?

Peter LoPilato: Well it was nice to see that at least somebody recognized that we were doing some interesting programming, somebody outside of Bloomington, sure, absolutely. I mean our programming is good and I would put our programming, I say with all modesty, I would put our programming up against one of the better art-house theaters in New York or LA.

Yael Ksander: Let's go back in time just a moment, even before the Ryder, and tell us, Peter, about where you came from. I mean, you're an East Coast guy. You came here for school.

Peter LoPilato: I used to be an East Coast guy. I've been here too long now. When I'm in New York I'm bumping into people all the time because I'm not moving fast enough.

Yael Ksander: Right, we all become Hoosiers in the long run.

Peter LoPilato: Well, I came from Westchester County, it's one of the suburbs of New York City, and came out here to grad school, masters program in English. Did some writing for some alternative magazines in town at the time, and was hearing about films in New York City from friends of mine that we weren't seeing here in Bloomington. So that's kind of where the idea came from. I talked to a couple of film programmers and the people who booked the Von Lee Theater, at the time, and they gave me some pointers, gave me some tips, told me who to talk to and who to call, and just gave it a whirl.

Yael Ksander: So you were a film buff, not necessary a...

Peter LoPilato: I wouldn't call myself a film buff. I was a film fan. But no I mean I know more about 60's rock n' roll and baseball than I do movies.

Yael Ksander: Was there a moment that convinced you to do this back in '79, was it?

Peter LoPilato: Yes, I think it was '79. Boy, I can't remember that far back. I do remember there was a time maybe two years into where I thought, this is working really well and this can continue to work indefinitely. We started out showing films one night a week so it was very small. It was one night a week and it was one screening a week. It was on a Wednesday night, and then we slowly expanded to maybe two screenings on that Wednesday night, and then we added a Saturday night. Then we added a Friday night, and right around then I started thinking, you know, this could work because we can show interesting films and there's certainly an audience for it, and it works really well with the magazine in terms of them working together to increase the profile of The Film Series in the community.

Yael Ksander: The magazine came first, correct?

Peter LoPilato: The magazine came first, Film Series came about three or four months later.

Yael Ksander: Were you still in grad school when all this was happening?

Peter LoPilato: No, I'd stopped taking classes and I never did get that masters.

Yael Ksander: Life took over. Let's go back to that moment in '79, considering the culture of Bloomington at the time.

Peter LoPilato: Yeah, Bloomington was a Wild West at that time.

Yael Ksander: How so?

Peter LoPilato: It was really anything goes.

Yael Ksander: Demographically or cultural offerings, or how do you mean?

Peter LoPilato: In terms of lifestyles. In terms of the way people approached their lives. I mean I think back to the decade of the late-70's and even the first half or two-thirds of the 80's, and I cringe, because in retrospect I'm not sure exactly what I was doing on a certain level. But at the same time, that catch as catch can approach to life and projects are what perhaps made something like the Ryder Magazine, the Ryder Film Series possible. Because we certainly didn't start off with investors in tow or anything like that. We just had to make it on our own and make it pretty quickly too. Before we published the first issue of the magazine I went out and sold all the ads and convinced people to pay in advance so we could pay the printing bill. I don't think we would do things that way today.

Yael Ksander: So just a real DIY or punk, entrepreneurial spirit.

Peter LoPilato: Yeah, yeah.

Yael Ksander: That's exciting. So what other kinds of things were happening at the time? In terms of visual arts or the music scene?

Peter LoPilato: As there are now, there were clubs. Well there were folk singers, but there were punk bands in Bloomington and as a matter of fact, The Gizmos, that group pre-dated The Ramones and their debut Bloomington album, last year, after 30-some odd years, went gold. If you include demos, yeah.

Yael Ksander: Wow, that's cool.

Peter LoPilato: I mean I was living in the Allen Building. I don't know if you know, it's above where the Uptown Cafe is now. It was like, it's hard to describe but it was a bunch of artists lofts. It was kind of like Chelsea Hotel in Bloomington. There were people doing all kinds of neat stuff in studio spaces across the hall and up the hall from mine and we all was one big... It had Seinfeld element to it because no one locked their doors and people just walked into other peoples apartments at all hours, as Kramer would in Seinfeld.

Yael Ksander: That sounds like a lotta fun.

Peter LoPilato: I mean it was an energetic scene there. There were a lot of people doing interesting stuff.

Yael Ksander: And so you were writing about all these happenings in the magazine?

Peter LoPilato: Yeah, actually, initially, I was writing some alternative papers in Bloomington and that was an education in and of itself. I mean, I didn't have a background. I really didn't have any background at all in journalism, but I learned as I went along. Everybody participated. Everybody helped out in whatever way they could. So, over time I learned about layout, I learned how to cut and paste, when cutting and pasting meant using an Exacto knife and rubber cement. Sold ads, did copy editing for those publications. Drove the paper to the printer and learned how a newspaper gets printed. And then as those publications tend to do over time, the people that were putting the most time and effort into it moved on and did other things, and they folded. I was still here and had some ideas for how something could be done a little differently, and that's when we started The Ryder.

Yael Ksander: When I think back to the 80's and the explosion of desk-top publishing, that wasn't until the late-80's, so we're talking about something that was happening ten years earlier, in terms of your publication.

Peter LoPilato: That's right, yeah.

Yael Ksander: So you weren't doing this on a computer in other words.

Peter LoPilato: Well no, I mean we typeset on computers, on typographic equipment. But these were large computers that were the size of this room. But no, the magazine wasn't being created digitally.

Yael Ksander: By quark or something, right.

Peter LoPilato: No, there were gallies, and you cut them up into strips that were three inches wide and then you put rubber cement on the back and you pasted them on a big board and stripped photos in. I mean it was pretty primitive, but that's just the way it was done.

Yael Ksander: Well, speaking of technology, it's important to remember what one could access with regard to film in 1979. We didn't have Netflix!

Peter LoPilato: No, we didn't. I think we may have HBO. Did we have HBO?

Yael Ksander: I'm not sure. Not only that though, most of us have VCRs.

Peter LoPilato: Right. That came a little bit later.

Yael Ksander: So, my point being, it was hard to see an old movie unless you happened to catch it on TV.

Peter LoPilato: That's true.

Yael Ksander: Maybe I'm pausing too much on this, but I think helping people to understand just exactly how different our cultural offerings were at that time.

Peter LoPilato: For sure.

Yael Ksander: Not only in Bloomington, but everywhere and what you made available. So, in those early years, what were some of the movies you chose and what was your thinking, in terms of your choices?

Peter LoPilato: We were limited by budget, and one of the goals was to have as much variety as we could, given our somewhat limited budget. So we weren't showing contemporary movies. In 1979 we weren't showing movies that were made in 1979, that came along a year or two later. So, it was black and white American films from the 30's and and 40's. I think our first film was, "His Girl Friday" with Cary Grant, Rosalind Russell and Ralph Bellamy. And then we showed some classic foreign films. I'm pretty sure we showed "Rules of the Game". At the end of the semester that year we showed "It's a Wonderful Life" which had never been screened in Bloomington before.

Yael Ksander: Really?

Peter LoPilato: Really, including 1946, as best I can tell, when it was released, because it was a box office failure at the time it was released. It came out right after World War II. The movie that won the Academy Award that year for Best Picture was "The Best Years of Our Lives" which is a very different movie, and the feeling is that the American public really wasn't in the mood for that sort of sentimental, Frank Capra sensibility. Yeah.

Yael Ksander: Right. So, how long did it take before the film had a renaissance?

Peter LoPilato: Oh, well you know, that's interesting. It was such a flop that the copyright was not renewed, and so it fell into the public domain, and since it was in the public domain, local television stations started picking it up and showing it late at night because it was free, and that would've been some time in the late 70's. So it was right around that same time that people started finding out about it.

Yael Ksander: Wow, and so series such as yours recouped the movie and put it back into circulation and made it the absolutely beloved cinematic experience that it is.

Peter LoPilato: Oh yeah. I mean, when we showed it the first time, most of the people there had never seen it. Which is kind of hard to believe. But I remember the first time Donna Reed comes on the screen and she's playing a high school student, she's at a dance in the local high school and people in the audience gasped because they had seen her on her television show where she played a suburban mom, but they'd never seen her looking like that.

Yael Ksander: Buffalo girls won't you come out tonight. Oh wow, that's something. I mean that's movie history and that's playing a role, because you can only imagine that series and small movie houses around the country all joining together doing the sort of thing that you did, and programming in the way that you did, resuscitated the film, and so many others along the way, and propped up films. I mean, all the way to last year when you showed the French film that didn't make it to LA. So kudos.

Peter LoPilato: Thanks.

Yael Ksander: What about growing the Series and partnering with the various venues that you did along the way that called the series a movable feast simply because the Series doesn't have it's own dedicated space, it exists throughout town. How did you set that whole thing up?

Peter LoPilato: Well, the first films were shown in what is now, what is it now? It's right on Eighth and Walnut. It's closed now, but it was a club. At the time it was called Time Out. It was owned by a IU basketball player named Archie Dees, who passed away last year. I knew the manager and I had the idea for showing films in the club and we did four films there, and then he sold it. So then we moved to Bear's Place right after that.

Yael Ksander: Where it remains.

Peter LoPilato: Where it remains, Sunday nights, yeah.

Alex Chambers: It's time for a break. This is Inner States and we're listening to a conversation Yael Ksander had with Peter LoPilato, who founded The Ryder Magazine & Film Series here in Bloomington. Peter passed away on March 7th. After the break, we'll hear how the Film Series audience went from being a bar audience to people who actually wanted to see the films. Stay with us.

Alex Chambers: Inner States, Alex Chambers. We're listening to an interview Yael Ksander did in 2016 with writer, Film Series founder, Peter LoPilato. He passed away on March 7th.

Yael Ksander: What were your audiences like, off the bat?

Peter LoPilato: Well, years ago initially when we started, it was a bar audience. It was very much the same people who would go to The Bluebird on Friday night, might come to Bear's Place on Sunday night and see a movie. It was young audience and it was a hipster bar crowd. Now, if you come to one of our movies, more than 50 percent of the people there have gray hair. It's a much older audience, and it actually might have even been true in the 80's. Over just a few years, the audience evolved from one that was just interested in hanging out in a bar and whatever happened to be going on might be fine for them, to people that were a little bit more interested in Series Film.

Yael Ksander: Then you teamed up with You Too, you show films in a number of classrooms.

Peter LoPilato: Well, yeah, we screen at the IU Fine Arts theaters. There were some professors on campus who wanted their students to see at least some of the films that we were screening and they weren't old enough to get into Bear's Place, 21-years-old. So they made the arrangements for us to move the Series onto campus.

Yael Ksander: As you mentioned, professors were extremely interested, probably in partnering with you in terms of your programming. Now that IU Cinema is on the scene there's a very formal relationship between professors and curricula, and the cinema. How do you fit into that mosaic?

Peter LoPilato: Well, The Ryder co-sponsors the art-house Series at the IU Cinema. We've got a great relationship with the cinema. John Vickers is great to work with, and we have a very similar tastes in programming. Sometimes we do some screenings together.

Yael Ksander: I remember a few years back you co-sponsored a presentation by Crispin Glover at the cinema when he came and showed some of his wacky movies.

Peter LoPilato: Oh sure! Yeah. Yeah, that was quite the experience.

Yael Ksander: I'm sure that you showed "River's Edge".

Peter LoPilato: We did show "River's Edge", yeah.

Yael Ksander: So that was like coming full circle, right.

Peter LoPilato: Mm-mm. Coming full circle in those terms, at least for me personally, was when Werner Herzog was at the IU Cinema, because very early on in our Series, we screened his film, "Aguirre, the Wrath of God" and if you had told me, whatever year that would have been, 1982 or thereabouts, that years later I would be standing next to him at the back of the cinema, in this case watching the film with him, you know.

Yael Ksander: Well, it's exciting that Werner Herzog and Crispin Glover, John Sayles, and Whit Stilman, Penelope Spheeris, Spike Lee and so many film-makers are coming through Bloomington, that we're really on the map.

Peter LoPilato: And really there are so many more than that. I mean those are the A list, but you know, there are two or three film-makers every week at the IU Cinema.

Yael Ksander: Yeah, and it seems to me between cinema, between what you're doing and the Fledgling Film Festival, the Middle Coast Film Festival and some of the film-makers who are trying to make things happen here, that Bloomington is sort of on the map nationally. I mean how would you talk about it?

Peter LoPilato: Well I think we certainly are. I think visiting film-makers who come here speak very favorably of it after they leave, I'm sure they do. I mean people are certainly more aware of Bloomington and more of a movie scene than ten years ago.

Yael Ksander: I know you regularly attend the True/False Festival in Columbia, Missouri.

Peter LoPilato: Yeah, they know about it.

Yael Ksander: So, how would you say Bloomington compares to a town of comparable size, in terms of it's film culture?

Peter LoPilato: It's interesting. The programming here, the programming at the cinema is exceptional. It's better than the programming at any other comparable theater, it really is. However, the film audience here is a little bit different. I don't know, I'm not real sure why that is. But when you ask about film culture, it's here, it might not be as large as some other college towns that have more urban populations. It's not just Bloomington versus Columbia in Missouri either. It's not just Bloomington versus Ann Arbor or Madison. I mean, it's really more than that. It's the whole... Look, I talk to 18 and 19-year-old students. I had this conversation about four or five months ago with an intern, so it would've been February, and I asked her, "Have you seen any of the Best Picture nominees?" And she said, "Well, no I haven't, Peter. I've been really busy lately and I haven't had a chance to download them."

Peter LoPilato: First of all, it never occurred to her that I was talking about seeing them in a movie theater, and then secondly these films are in commercial distribution, so they weren't available for download. Unless of course you spend time in the netherworld of the dark web. That's what she was talking about and I think that's true of a lot of my projectionists, they watch movies that way all the time and I think that's true of a lot of college students.

Yael Ksander: That's sad.

Peter LoPilato: Yeah, it is sad. I had another conversation with another intern and we were talking about, this was a few years ago, I think Antonioni and maybe Ingrid Bergman died within a week of each other, and I was talking to her about, "Yeah, back in the 70's when people went to the cinema and then they went to a café afterwards and they talked about the movie." And she said, "Well Peter, people still do that, they just talk in chat rooms."

Yael Ksander: How about that? I mean, let's talk about the collective film experience.

Peter LoPilato: It's still there and it's disingenuous for me to say, well it's not still there for the movie that won the Best Picture at Cannes, maybe it's not. But, just because tastes have changed, I mean, I could talk to you for 30 minutes about why foreign films today are not as hip as they were 25 or 30 years ago. But people still go to movies, whether it's the "Harry Potter" series or whether it's the newest Jason Bourne movie, people still got to film, and they still go to film in pretty large numbers.

Yael Ksander: Hence the graying of your audience. So, would it be accurate to state, based on what you're saying, that the audience, at least in Bloomington, Indiana, for so-called art house, international or repertory films is not renewing itself?

Peter LoPilato: It's more challenging to get it to renew itself and maybe the right way to answer that is to say that I have to a little bit more actively help them to renew it. You know, years ago we showed films on 16mm film. We had clunky projectors and reels of film. We're much more portable now than we were then, so we can go to different locations on campus and screen films in student lounges and really anywhere. You know, micro-theaters are popping up everywhere.

Yael Ksander: So, you really have to be an ambassador for the film experience.

Peter LoPilato: Well, I've always been an ambassador for the film experience but yes, perhaps a little bit more so.

Yael Ksander: Keeping any business going for 37 year is really impressive. Have there been moments when you wanted to throw in the towel, or felt like you were going to have to?

Peter LoPilato: Once a week.

Yael Ksander: How's that?

Peter LoPilato: I mean, you know, nobody gets rich showing foreign language films and documentaries, otherwise everybody would be doing it. But, having said that, I enjoy the movies and I thoroughly enjoy what I do. You know, one of the things that makes it worthwhile is it's nice when you get, and this happened a few weeks go, I got an email from somebody, I didn't know 'em, and he said, "I saw a movie at your Film Series about 25 years ago involving a nasty dog, and I've been trying to find that movie and I can't remember it."

Yael Ksander: Wow.

Peter LoPilato: And so I was able to answer his question. He was very happy about that. Or, you know, when somebody just stops you on the street and says, "Hey Peter, I saw that movie last week and I really liked it." Or, "I read an article in your magazine and really appreciated that." So yeah, sure that's what makes it worthwhile.

Yael Ksander: Those kinds of connections, yeah.

Peter LoPilato: Yeah, absolutely.

Yael Ksander: You know, at this point, 37 years later and still going strong, I would beg you to consider the question that the Angel Clarence asks of George Bailey in the film, what would've happened had you not done this?

Peter LoPilato: Well, someone else would've done it. Bloomington would be exactly the same, someone else would've done it.

Yael Ksander: Are you sure about that?

Peter LoPilato: Yeah, I'm pretty sure.

Yael Ksander: Well, you did have a near-death experience at one point. Would you tell us the story?

Peter LoPilato: The parking garage on Sixth Street, across the street from The Runcible Spoon was being built, the street was open to traffic and I was driving down the street and a large piece of cement fell from a crane onto my car while I was driving. It weighed 22 tons. It was actually intended to be one of the ramps for cars to drive on. So what happened was the crane operator had lost control of the crane and he just dropped it. He thought the street was closed off, and it wasn't, and had I been in the back seat I probably wouldn't be here speaking to you.

Yael Ksander: But you were driving.

Peter LoPilato: Yeah, I was driving and I was pretty lucky. The car was crushed. Every window was completely shattered and they had to cut me out with the jaws of life.

Yael Ksander: I heard that you had a cappuccino in your hand.

Peter LoPilato: I don't think I had a cappuccino in my hand.

Yael Ksander: And that you didn't spill it.

Peter LoPilato: That's urban legend. No, I didn't have a cappuccino in my hand. I was very fortunate. I mean, I didn't actually have a scratch on me. I mean, I took off my shoes and my shoes were filled with shards of glass. My hair was filled with shards of glass, but I was perfectly fine. The scariest part was I was in the car for maybe 30 minutes or so before they got me out, and I was lying flat on the seat, because the roof of the car was crushed in. When the beam first landed on the car everything got dark because it was a sunny day and this large beam just completely covered the car. Actually, I was told later that the car was like an accordion effect, where it went down and bounced back up and then came down again. There were three different times where the roof caved in a little bit more and each time that happened it was pretty scary.

Yael Ksander: Do you remember any thoughts from that?

Peter LoPilato: Yeah, I do remember thoughts. I was trying to concentrate on anything else. I was going through my utility bills in my head, which ones I'd paid and which ones I hadn't.

Yael Ksander: The important stuff.

Peter LoPilato: Yeah, and then I was trying to remember the last time I looked at the batting averages in the American and National League and I was trying to see if I could just list the players, the top ten players. That sort of thing. It's kind of hard to describe, but on the one hand I felt pretty calm and I had the presence of mind to turn off the ignition. But on the other hand I think I was probably terrified.

Yael Ksander: Wow, it's so interesting that you went to such utterly prosaic thoughts in that moment. You weren't thinking...

Peter LoPilato: What? Batting averages, prosaic?

Yael Ksander: Oh sorry, that's very important. Well, what I understand though speaking of legend, is your experience spawned quite a legend. The story was picked up on the AP wire, is that correct?

Peter LoPilato: Oh yeah.

Yael Ksander: Tell me about the publicity that you received.

Peter LoPilato: It was the worst publicity imaginable. It really was. I was getting calls from people all over the country who thought I had been saved for a reason and one woman wanted to pitch a tent in my back yard.

Yael Ksander: You got a lot of fan mail?

Peter LoPilato: I wouldn't call it fan mail.

Yael Ksander: Was this a before and after kind of thing for you?

Peter LoPilato: No. Was a life-changing experience? Not really. But after I got out of the car I said to myself, well apparently I've survived this and I probably shouldn't have. So, I thought okay here's what I'm gonna do. I'm gonna stop putting stuff off.

Yael Ksander: Well, we're glad you survived the incident, Peter, and what would Bloomington be without you? Anyway, I think that's all the time we have today.

Peter LoPilato: And that's enough.

Yael Ksander: Thank you so much for being here with us.

Peter LoPilato: Thanks for inviting me.

Alex Chambers: That was Ryder Film Series & Magazine founder, Peter LoPilato, in conversation with Yael Ksander. Peter passed away on March 7th. You've been listening to Inner States from WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana. If you have a story for us, or you've got some sound we should hear, let us know at WFIU.org/InnerStates. Okay, we've got your quick moment of slow radio coming up, but first the credits. Inner States is produced and edited by me, Alex Chambers, with Avi Forrest. Our social media master is Jillian Blackburn. We get support from Eoban Binder, Mark Chilla, LuAnn Johnson, Sam Schemenauer, Payton Whaley, and Kayte Young. Our Executive Producer is Eric Bolstridge. Our theme song is by Amy Oelsner and Justin Vollmar. Music for the Netmakers Story by Mark Chilla and Amy Oelsner. We have additional music from the artists at Universal Production Music. Alright, time for some found sound.

Alex Chambers: That was a muddy, late-winter hike at Griffy Lake in Bloomington, Indiana. Until next week, I'm Alex Chambers. Thanks as always for listening.