Alex Chambers: When he was young, Monroe Anderson had a plan. It was the 1960s and--

Monroe Anderson: I was going to be James Baldwin.

Alex Chambers: He was going to be a novelist. Then his class got a visit from Les Brownlee, a pioneering black journalist who worked for the Chicago Daily News. Brownlee said now is the time for young black writers to get into journalism.

Monroe Anderson: So I decide I'll see what this journalism thing has. I'll try it out for a year or so and then I'll write the great American novel.

Alex Chambers: Then he covered the 1968 Democratic National Convention. He was tear-gassed alongside Katharine Graham. Another decade and a half and he predicted Chicago's first black mayor. The ink was in his blood. This week on Inner States, Monroe Anderson on objectivity, racial politics in Chicago, and why he couldn't quit journalism. Coming up after this.

Alex Chambers: It's Inner States. I'm Alex Chambers. After Donald Trump was elected President, journalism realized it had a dilemma on its hands about what it meant to be, quote, unquote, "objective". At the beginning of 2017, for example, Lewis Raven Wallace wrote a post on his personal blog saying, "Objectivity is dead and I'm okay with it." He was working for NPR's Marketplace at the time. They asked him to take it down, saying it didn't comport with expectations around objectivity. He refused and he was fired. He has since produced a podcast and written a book called The View From Somewhere: Undoing The Myth Of Journalistic Objectivity. He argues that, quote, unquote, "Objective journalism usually benefits the people in power and this dynamic has been at play long before President Trump." That question of what it means to have a position, to care about a particular group of people, say, and to have strong opinions and to maintain your integrity as a journalist, that's part of what I was interested in when I invited Monroe Anderson to sit down for an interview.

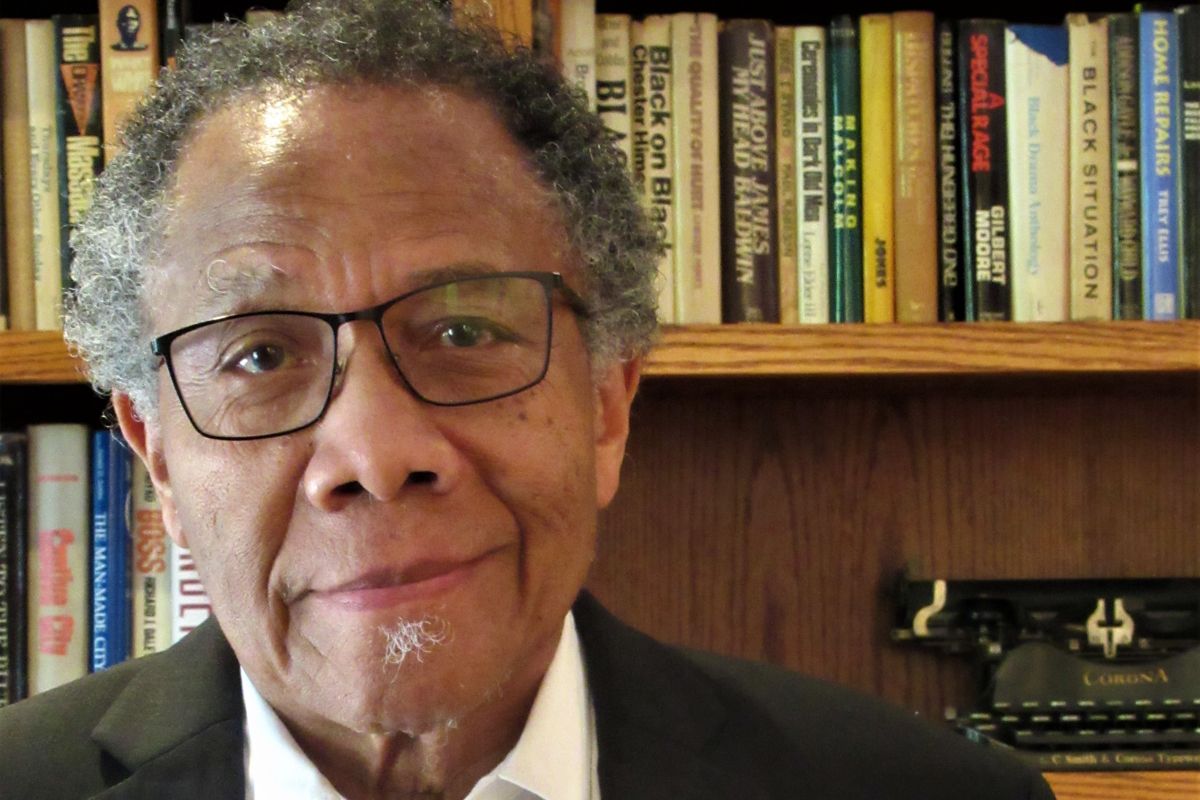

Alex Chambers: Monroe Anderson is a veteran journalist and columnist. He's worked at News Week, Ebony, the Chicago Tribune and other papers. He hosted a TV show called Common Ground for eight years. And he was the press secretary for Chicago mayor, Eugene Sawyer. Before all that, he was in intern at News Week, when he went to cover the 1968 Democratic National Convention. While he was there, he was among the journalists who were beaten by the Chicago police. He was a student here at Indiana University at the time and I'm talking with him while he's in town to accept a distinguished alumni award from IU Media School. Monroe Anderson, welcome.

Monroe Anderson: Thank you. It's good to be here.

Alex Chambers: Great to have you.

Monroe Anderson: Okay, now, with objectivity, let me-- let's start there.

Alex Chambers: Sure.

Monroe Anderson: That's your intro. Objectivity is a modern construct in journalism. When newspapers began, before the Revolutionary War, whoever could afford to buy a printing press printed their own propaganda, and that continued all the way up to the good old days of yellow journalism around the turn of this 19th century, to the 20th century. The 1800s[LAUGHS]. Anyway, when, when they had the, the penny rags at that time, and those were not objective because their audience was immigrants. And so, wherever you were from, they were sort of in favor of you and whatever you thought, they would sort of favor that and who you disliked are the next ethnic group, immigrant group that was coming in, that you didn't like, they were against that. For, for example, the Chinese were treated horribly, during their era of serious immigration. The Irish obviously, we know, no, no dogs or Irish allowed, that sort of thing. So, so this idea of objective journalism is a nice idea as such but it had a very brief life because now we have almost none of that.

Alex Chambers: What is your understanding of the, the rise of that idea?

Monroe Anderson: Well, from my professional perspective, it was a pretense when it, when it was there. You know, for example, when I was at the Chicago Tribune, and Harold Washington was running for mayor, the Tribune was not interested in black journalists covering it, because they thought we would be too slanted, too favorable to, to Harold, and since almost none of the editors there wanted Washington to win, they didn't want any of that. Now, had it been a candidate that they really wanted, then it wouldn't have bothered them in the least bit.

Alex Chambers: Right, it wasn't a problem for white journalists to be covering white candidates.

Monroe Anderson: Exactly. Or Jewish, or Jewish, yeah. Because I, I pitched them at one point to send me to Africa, to cover Africa, and they weren't interested in Africa at the time, so they gave me some other excuse, but they would do the same-- the-- you might be too s-- sympathetic to, to the beat or something, but it didn't-- it wasn't a problem for a Jewish reporter, journalist, to cover Israel. You know, so it's just-- it's, it's been a pretense but I don't think it's really existed.

Alex Chambers: Right.

Monroe Anderson: And so, you know, and so my, my-- when I taught-- I've taught journalism and what I would teach my students is that being objective is impossible because you come with biases just as a human being, but what you should strive to be is fair. So, if you would cover one person one way, then you should cover the other person the same way. And that works out.

Alex Chambers: Though I think even that, I think one of the things we've seen, you know, in the recent past at least is this idea that covering sort of two sides of an argument...

Monroe Anderson: Yeah.

Alex Chambers: ...is always the thing to do, even if, say, the preponderance of agreement is--

Monroe Anderson: Oh, no, Tr-- Trump blew that up.

Alex Chambers: Right, right, right.

Monroe Anderson: Because I, I would watch journalists try to do this, he-- well, he said this, you know, meantime it would be, well, this guy said the sun rises in the east and Trump said [LAUGHS] it rises in, in the west, you know, just, just as strongly and, and they were reporting it, like, okay, that was it, they'd done their job, whereas they should have been saying, "Liar, liar, pants on fire."

Alex Chambers: Right. So, when you were, when you were sort of coming up in your career, for example, when you were at IU...

Monroe Anderson: Okay.

Alex Chambers: ...and you were involved in a, a black nationalist group...

Monroe Anderson: Yeah.

Alex Chambers: ...who, you know, had this-- did this protest.

Monroe Anderson: Right.

Alex Chambers: And you had, you had mixed allegiances, I think, right?

Monroe Anderson: Very.

Alex Chambers: That was the challenge for you?

Monroe Anderson: Very, very. This was--

Alex Chambers: Tell me about that.

Monroe Anderson: This was, this was my problem. Okay? After I completed my internship at News Week in Chicago, I had the dubious distinction of being one of the first journalists beaten by the Chicago police and that made me a star [LAUGHS]. And so, they flew me to New York and-- New, News Week did, and they-- I was on a, a radio show and 21 years old at the time, I was on a radio show and I was-- I, I spoke to an audience of people in New York, I'm not sure. You know, they said go up there and tell them about your experience in two minutes or less, you know.

Monroe Anderson: Anyway, so, I'd done that and I had become, as a result of that, big man on campus, from a journalist point of view. So, the Indiana Daily Student offered me a job, part-time. I had 20 hours a week but it was, it was a very nice job and it was some more experience. And so, I did the job, but I was also a--hanging out with the black students, or back in those days, the black militants, because as, as-- if you had a BAA student who was interested in politics and race relations, that's where you had to go with it and that was fine with me. So, anyway, I'm in a series of meetings with these people after the tuition. They now said they were going to raise the tuition.

Monroe Anderson: And, yeah, just for those of-- who are here now, who may listen to this, in 1965, tuition at Indiana University was $15 a credit hour. So, if you took 11 of-- how many hours? Anyway, it would be about 165 when it--

Alex Chambers: Right.

Monroe Anderson: It ended up there, something like that.

Alex Chambers: Amazing.

Monroe Anderson: And so they were, they were raising it, for some strange reason. They said--

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS].

Monroe Anderson: And the black students, in these meetings they were having, looked at it as a plot to reduce the black population in Bloomington. That was their theory, and that they were trying to get us out-- off the campus, so they were raising the, the--

Alex Chambers: What did you think of that?

Monroe Anderson: I thought it was nuts. [LAUGHS] I thought it was nuts because, like, I mean, they weren't raising it just for black students and it didn't raise-- I don't remember what it was, but it wasn't like it went from $15 an hour to $50 an hour, something like that. So, I can't remember the, the number. But-- And in the meetings I sort of voiced that but not strongly because they were leaders and I was just one of the crowd. So, anyway, they planned the-- they, they planned a demonstration, have their list of ten, ten non-negotiable demands of-- one of which was to rescind the tuition increase, and at that time, I'm working for the news bureau.

Monroe Anderson: And so, I, I go with the black students and you have all-- you have the, the-- all the top leaders of it-- the univers-- IU, the, the chancellor, I think was the title, and, anyway, the people who actually run the--

Alex Chambers: President and the chancellor, yeah.

Monroe Anderson: President, yeah, exactly.

Alex Chambers: Right.

Monroe Anderson: They're all in this meeting.

Alex Chambers: Mm hm.

Monroe Anderson: And we walk in, and the first person I notice is John Newman who was my boss [LAUGHS]. And I go, oh, my god, and so I make a pivot and I start going the opposite way of the students, and everybody is looking at me very strangely, like, where are you going? And so, and then I go, hm, how do I get out of this? And it so happens that I have my reporter's notebook in my pocket, so I walk back in boldly, walk over to John, bend down on one knee and I just pat him on the back and say, "Don't wo-- worry, John, I'm covering this." [LAUGHS]

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS].

Monroe Anderson: And I did. You know, I, I was there with the black students but I was interviewing everybody. And so it worked out, but it, it was quite frightening for-- co-- concerning for me, initially.

Alex Chambers: Did that shape how you thought about journalism?

Monroe Anderson: Yeah. It did. It did, yeah. Well, let's go back to my actual internship. Okay. Before I did the internship, I wasn't really interested. I, I had no ink in the blood. When I was in seventh grade at Roosevelt High School in Gary, my English teacher pulls me aside and says to me, after I'd done a paper, he says, "You are a writer, you're really talented, you are a writer." I'd had teachers tell me that I was smart or this or that, but no-one had assigned a specific talent to me. So, from that point on, I quit studying my math. I thought of myself [LAUGHS] as a writer. I became editor of the Junior High, eighth grade, page in the high school newspaper. I, I went on to be editor of the newspaper, but I thought of myself as a writer. And so I was going to be James Bowen. And then we got a visit from a black journalist from Chicago. He worked for the Chic-- His name was Les Brownlee. He worked for the Chicago Daily News and he came over and talked to our class, journalism class, and he said now was the best time for us to go into journalism, because things were changing.

Monroe Anderson: So, I go home and tell my mother that I'm going to be a journalist and she looked at me and says, "There are no Negro journalists. Be-- Teach school. Be a school teacher." I had literally just told her, said the, the field was open and it, and it also tells you how long ago that we, we were Negroes in 1964.

Alex Chambers: Right.

Monroe Anderson: You know, but it-- anyway, so, I decide, well, I'll, I'll see what this journalism thing has and I'll still become-- I'll try it out for a year or so and then I'll write the great American novel and fulfill my dreams. And so that was my thinking, even though, as I came down here, Miss Kemp was my counselor, see, it was a long time ago but she was well known at that time in the department, and she tells me--

Alex Chambers: In, in--

Monroe Anderson: Journalism, right?

Alex Chambers: In the journalism department here?

Monroe Anderson: Department, yeah.

Alex Chambers: Okay.

Monroe Anderson: Anyway, she said three things to me I remember. First of all, I sit down to talk with her and she, she asked me if I have a pen or pencil and I say no and she says, "No good journalist ever travels without a pen or a pencil," [LAUGHS]. And then she says, "And, Monroe Anderson, that's gonna make a great byline."

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS].

Monroe Anderson: [LAUGHS] And then she says to me, "Do you realize if you graduate with a degree in journalism from Indiana University, you'll be able to write your own meal ticket." At 18, the idea of writing my own meal ticket was intriguing and so, I, I took that into consideration, although I still want to be g-- the novelist. When I covered the Democratic National Convention, besides being beaten on the first night by the cops, and we-- after we were beaten and we were pulled off this-- we was part of the street team, we were put in the office. John Culhane, who's the real job-- journalist, correspondent and, and me, we were pulled off because they thought we had done something to provoke the police and that was on a Sunday. Monday we were pulled off. The cops were beating the living daylights out of everybody. It was a police riot. And so, by Tuesday they were-- realized it wasn't us, it was them.

Monroe Anderson: So, we were back on the street and covering it was just very exciting. We were chasing police, chasing demonstrators. We needed to make a phone call and we went into Sarg-- the, the Kennedy relative.

Alex Chambers: Sargent Shriver?

Monroe Anderson: Sargent Shriver.

Alex Chambers: Okay.

Monroe Anderson: Exactly, right. We went into his hotel room and made a call from there. And during the process of this, I met all these famous people. Katherine Graham and I were tear-gassed together. We started there, you know. And it occurred to me that as a journalist, A, you got to, you got to meet all these famous people and, B, you watched history as it unfolded. And, so, the ink was in my blood from there on. And I, I still wanted to write a novel but journalism was just far too exciting. In fact, when I was in New York, and, and spoke before this audience, afterwards I was approached by this guy who told me that he was a Yale Law School alumni and that he wanted to sponsor me and get me into Yale Law School. And I, I didn't give it a second thought. I wanted to be a journalist [LAUGHS], you know, although now I look back on that, I could have been Clarence Thomas [LAUGHS].

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS].

Monroe Anderson: Except our politics are a wee bit different, but, but, anyway, so, I'm, I'm--

Alex Chambers: Well, so, how-- I was, I was interested in how, like, that other moment too, here at the protest also sort of shaped.

Monroe Anderson: Exactly. So, that sh-- That-- Yeah, that shaped me because I realized there was two sides to every story, literally. I mean, I, I've witnessed it, because, because I was working for the IU News Bureau, after the protests were over and the President has had a heart attack or something. He had, he had a medical condition where they took him out on a stretcher, so it was international news. My job, since I was covering it for, for John, my job was to write a press release, talking about the protest and what happened and what have you.

Alex Chambers: A press release?

Monroe Anderson: For me-- media. You know, the News Bureau, what PR departments do, that sort of thing. Oh, the other thing which I'm leaving out, sorry about that, is I was also campus correspondent for News Week. So, I had to write a report to News Week for them to publish about it.

Alex Chambers: Right. A journalistic account.

Monroe Anderson: A journalistic account. So, I had to do both.

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS].

Monroe Anderson: And, and I did it. But working for the IU New Bureau convinced me that I didn't want to do PR. I wanted to do real journalism.

Alex Chambers: Why?

Monroe Anderson: Why? Because I knew what had happened as, as a protesting student, but my job in the News Bureau was to put a, put a pretty face on it for the University, where things looked good and sounded good. And, and I wa-- And I was a student, so it's not like I was good at any of this [LAUGHS], you know. I can do a much better job today than I did back then.

Alex Chambers: Sure [LAUGHS]. I didn't fully understand that the News Bureau here was the PR wing of the university.

Monroe Anderson: It was the PR-- yeah, yes. It was the PR side. Yes, exactly.

Alex Chambers: Which we still have.

Monroe Anderson: Okay, it probably has another name.

Alex Chambers: I can't remember exactly what it's called now.

Monroe Anderson: Yeah, right, but, no, it was a PR wing and they ca-- They called themselves the News Bureau.

Alex Chambers: It's time for a short break. When we come back, Monroe Anderson talks about being a young black journalist in the late 60s. It wasn't hard to get a job. It was hard to get assignments with any weight to them. That's on Inner States, right after this.

Alex Chambers: Welcome back to Inner States. I'm Alex Chambers. We're talking today with Monroe Anderson. In 1968, he was a student at IU and an intern at News Week. That summer he covered the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and he was among the journalists beaten by the Chicago police. I asked him how he ended up on that assignment in the first place.

Monroe Anderson: This is what happened. I've, as a student, worked as, as everybody did back then and I assume they still do, you had to write for the Indiana Daily Student, as part of your, your classes and what have you. As a black student, I couldn't cover s-- City Hall. That just was not going to work. Back, back in '68, the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross on the a black student's lawn here. These were different times, remember?

Alex Chambers: Yeah.

Monroe Anderson: And in fact year-- years later, I would become the first black reporter from a major white newspaper in Chicago to, to cover City Hall and this was in '83 wi-- with Harold Washington. So, in the 60s, in a small town Bloomington, where there were no blacks in power whatsoever, I doubt if anyone would have talked to me even. I don't know. But, anyway, the white students got that, got that job anyway. So, what I, I cu-- I carved out a area that no-one else was doing and I s-- I was doing movie reviews and I was doing feature stories.

Monroe Anderson: For example, I interv-- I interviewed The 5th Dimension when they came through, I interviewed Lou Rawls, that sort of thing. So, that was what I was doing, because there was no competition for-- and nobody cared.

Alex Chambers: The serious journalists weren't interested in that.

Monroe Anderson: Exactly. They weren't interested in it. And, later, I would become friends with Ebert and, and Siskel. In fact, Siskel and I worked together.And I wish I had been able to do their job [LAUGHS] 'cause they were a whole lot richer than any other journalist in Chicago, but--

Alex Chambers: That really changed, I guess.

Monroe Anderson: Yeah, right, that changed, yeah.

Alex Chambers: Yeah.

Monroe Anderson: But, anyway, so I'm in the news room. And I'm working on a review for something, it may have been for The Good, The Bad And The Ugly. Anyway, I'm writing the review and my photography teacher, Will Counts, comes through and there, there was no such thing as Googling somebody or anything like that back then, so I didn't realize that Will Counts was a very distinguished photographer. He had covered the Civil Rights Movement and had some, some shot that, that was distributed widely. And so he had a very good reputation. Anyway, he's coming through, he sees me and he comes over to me, and he says that News Week is expecting a long hot summer in Chicago.

Monroe Anderson: That meant riots. And that they were looking for a, a black journalist and that I should apply as an intern, that one of his students had-- former students, Marv Kupfer, who was at the Bureau at the time.

Monroe Anderson: And so, I sit down and I write up a, a letter and I send it to him and very quickly after I hear from him, I get a phone call and they say they would like to interview me, when could I come in. I say, well, I'll be home for spring break and I live in Gary, you know, Chicago's not that far away so I can do it then. And they said fine. My interview is the day before my 21st birthday and a day after Doctor King has been assassinated and the city is in-- it was west side and Chicago was in flames. It was the easiest job interview I've had in my life [LAUGHS]. So, that's how, that's how I got there. And, and the thing was, at that time, what the-- the transition that was going on was that, because of the riots, newspapers and magazines, TV stations, also, decided they needed at least one black because white journalists were becoming targets in those riots.

Monroe Anderson: And so, if you had someone who blended in, then that would be a good thing. And so, there was this rush for blacks in media that had not existed before. For example, at the Tribune, the first reporter they hired was a Chicago policeman who became a journalist, Joseph Boyce, and Clarence Page was the second one they hire there. Du-- During my internship, I was assigned to do a story. News Week was-- did a story, headline was, "How The White Press Attempts To Reach The Black Community." And there were four newspapers in Chicago at that time, the Tribune, the Sun-Times, the Daily News and the Chicago's American. The Tribune u-- owned two of them. The Sun-Times owned the Sun-Times and, and the Daily News. They owned that.

Alex Chambers: Right.

Monroe Anderson: I interviewed all four editors. All four of them offered me a job. [LAUGHS] Right after the interview and it-- and I said, no, I really do need to go back to Indiana University and, and finish my degree, 'cause it-- and, which I did. But those were different days at that time.

Alex Chambers: Yeah.

Monroe Anderson: One of the stories that I've covered was a-- was about Christmas and students' attitude toward Christmas and the people I hung out with were not your typical IU student. They were musicians and, and theater people and overall radicals. Right? And so, I'm interviewing all these folks and about Christmas, and they're saying, "Oh, Christmas is too commercial," you know, that sort of thing. Well, yeah, what radicals said back then.

Alex Chambers: Right. And still.

Monroe Anderson: So, I write-- Right, exactly. So, I write the story and my editor says, "Who are these people you are quoting?" [LAUGHS] 'Cause, you know, 'cause they were obviously expecting one of these warm and fuzzy, oh, Christmas is so wonderful, etc. [LAUGHS]

Alex Chambers: Right. Did you continue-- I mean, you've interviewed, you know, tons and tons of people. Did you feel like you continued to interview people with these different kinds of viewpoints, maybe more radical viewpoints in your career?

Monroe Anderson: Yeah, early on in particular. Yes. For example, let's go a little ahe-- ahead now.

Alex Chambers: Sure.

Monroe Anderson: My first job was with the National Observer out of D.C. as a-- owned by Dow Jones and I was the first black they ever hire and, and when I say the first black, I mean no janitor, no secretaries, no nothing, but me.

Alex Chambers: Wow.

Monroe Anderson: And they had done that because of the managing editor of the newspaper at that time, retired, and before he retired, there would be some qualified blacks who would apply and he would say, "Did you notice that this is a Negro?" and he'd put, put it in file 13. And so they, they swore that the first qualified black who applied, they were gonna give a job to and I was just-- it was just serendipity.

Alex Chambers: So, you were working for them and you continue at that point to interview maybe-- focus more on particular--

Monroe Anderson: Well, for-- Yeah, no, for example, I interviewed Iceberg Slim, I did a piece on him. Iceberg Slim was this pimp who became a pulp fiction writer and his books sold like hot cake and in fact, all of the-- not all, but several of the rap people with Ice in their name, it was after Iceberg Slim.

Alex Chambers: Oh, wow. I had no idea.

Monroe Anderson: Yeah, because he'd moved to California, but, you know, you have Ice Cube. You, you have-- Ice-T.

Monroe Anderson: Ice-T.

Alex Chambers: That's another one.

Monroe Anderson: Yeah, right, exactly. But all these guys had this worship for Iceberg Slim. He had moved to LA and, and his life story was incredible and he was a g-- he was really an interesting writer. I mean, he, he basically invented street literature. But I, I interviewed Ossie Davis. I went to New York to interview him and that was a, a moment for learning in that I interviewed him, I had a tape recorder and I interviewed him, you know, and then he, he talked to me for an hour. I turn off the tape recorder and there's nothing there [LAUGHS]. Just nothing. And I've not taken notes because I'm taping it. And I just panicked and he said, "It's okay," and he gave me another interview. You know, he let me have another hour to interview.

Alex Chambers: Amazing.

Monroe Anderson: Right, I know, I know, I know. But I interviewed Melvin Van Peebles, right after Sweet Sweetbacks Baadasssss Song. He just died a couple of weeks, two or three weeks ago. But his, his movie is in fact the blueprint for black exploitation.

Alex Chambers: So, did you feel like-- were you interviewing these sort of really interesting culture figures because you were still, because you were still connected to wanting to be a novelist or was it about carving out this niche still?

Monroe Anderson: No, it was, it was more--

Alex Chambers: Or because you just couldn't, as a black reporter, you couldn't do, quote, unquote, "hard news".

Monroe Anderson: No, I-- Yeah, no, I did some hard news but not a lot, because I had never really done it and...it was a problem for me, in that, okay, first of all, Amiri Baraka was my, my hero and so I was emulating, by writing, you know, it was like that. Now, as it turns out, because I did not have a hard news background, and because I was trying to write newspaper stories, like a, a Amiri Baraka... poem, it didn't work and so, after two years, they suggested that I really did no-- need to go work for a daily newspaper where I'd get that experience.

Monroe Anderson: I was so crushed and heartbroken that I decided-- and, and during that two years, I was still their only black there. I mean, still no janitors, no secretaries, just me. So, I applied to Ebony, and so I go to Ebony and I worked there for a couple of years. The best experience out of Ebony is that it was so lightly staffed that you, that you had to do everything. You, you know, you had to write fashion, you had to edit stories that o-- that freelancers wrote, you, you had to write your own captions for the photographs. When I went out on assignment, I had to make sure that the photographer got the photographs that we'd need for the story. I mean, you, you-- I got this very broad experience in, in that sense. You know, I, I met Billy Dee Williams back then. I went on tour with Curtis Mayfield right after Super Fly had come out. I toured with him.

Alex Chambers: Wow.

Monroe Anderson: It was a great experience in that sense but Mr. Johnson, and you had to call him Mr. Johnson, John Johnson, was-- he ran a plantation, you know, work began at 9 o'clock. If you got there at 9:01, you were late, and that's even if you had been there to 7 o'clock the night before working on a piece, it didn't matter. The lunch periods were dictated. The coffee periods were dictated. You had coffee from 9:45 to 10 o'clock, or something like that, up, up in the cafeteria, which was very nice. The building was incredible. And then you go back to work. Lunch was for 45 minutes in the cafeteria. Now, you could go out and, and not eat at the cafeteria, but the thing is, lunch was $1 a day. And it was this, this incredible soul food which was cooked [LAUGHS] and so, you-- and so, it was a no-brainer. Plus you got to f-- fraternize with your, with your, your other people there. So, you ate there and you ate there where they told you, for how long they told you.

Monroe Anderson: And being at the Observer, I had total freedom. It was like, if I wanted to work from home after I'd done the reporting, I could, I could stay home and write the story from there. Just-- They just were very hang loose about that. And so to go that very disciplined, confining situation, I couldn't take it much longer. So, I applied to the Tribune. I was accepted and I went and told Herb Nipson, who was the editor of Ebony, that I was going to go work for the Tribune and he says to me, "That racist rag? You'll be back here within a year." [LAUGHS] So--

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS] But when-- What was that-- But that wasn't your experience there? [LAUGHS]

Monroe Anderson: [LAUGHS] Are you kidding me?

Alex Chambers: I mean--

Monroe Anderson: To get there, okay, part of my negotiation, because I knew other black reporters and there weren't many, there were seven or eight. But I, I knew some of them and f-- what they told me was, "Don't let them put you on the Metro staff." That, that wasn't the name of it, but, again, it was almost 50 years ago so--

Alex Chambers: Sure. Like the city beat?

Monroe Anderson: Yeah.

Alex Chambers: Why?

Monroe Anderson: Because that's where they kept all the black reporters. They were-- You would get on there, you wouldn't get any good stories, you'd get the stuff that they didn't care about. And so, part of my negotiations was, I would not be on the Metro, I would be in the general assignment pool. And, you know, so, we-- co-- Because there was some black journalists, they would, they would bring most-- unless you came from another newspaper, they would bring most rep-- journalists, most of the journalists in but the white reporters, which spent three months there, maybe and then they'd get a, a beat or something else and they'd be out of there, you had black reporters who had been there for three years and they didn't-- you were writing stories that they didn't care about. And so it just was not-- you didn't-- you-- that was no way to advance your career.

Alex Chambers: Right. And you knew that going in?

Monroe Anderson: Yes, I knew that going in, so that was part of my negotiation and because I worked for Ebony and the National Observer, although I'd not covered any hard news, but I, I covered some--

Alex Chambers: You had these--

Monroe Anderson: And I, and I had clips.

Alex Chambers: Yeah, right.

Monroe Anderson: You know? So, so I, again, when I got there, I got a lot of obits [LAUGHS] to write.

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS].

Monroe Anderson: But sometimes, you know, I'd get a decent story and the other thing was, the, the fortuitous thing that happened to me, because you had to work weekends starting out, you didn't get off-- weekends off, I would cover PUSH, Operation PUSH every Saturday morning and I did that for years, I did that.

Alex Chambers: Can you describe Operation PUSH for maybe our younger listeners?

Monroe Anderson: Okay, Operation PUSH was J-- Jesse Jackson is a minister, a reverend, and he would have this Saturday morning meeting at PUSH headquarters and he'd have-- he would take on whatever crisis of the day that Jesse found, no matter where it was, he'd talk about it. You know, and the thing was, because I kept going, I went there every week...

Alex Chambers: Uh huh.

Monroe Anderson: ...I, I learned how it operated, PUSH operated. Jesse would do basically the same speech. So, it got to a point where I could quote Jesse, I didn't even have to take notes for the most part and I could quote him verbatim because I had heard the same lines, "I am somebody," etc. etc. but it, it would change, it would be a evolution, in that 10% of whatever he spoke about would be new. The other 90% he had talked about. You know, and it would move along like that, so-- which was interesting.

Alex Chambers: It's time for a short break. When we come back, Monroe Anderson talks about racial politics in Chicago and how he predicted the city's first black mayor, Harold Washington. You're listening to Inner States.

Alex Chambers: Welcome back to Inner States. I'm Alex Chambers. We're talking today with veteran journalist Monroe Anderson. In the early 1980s, he was working at the Chicago Tribune. As he watched the race to be the next mayor of Chicago, he realized there was a good chance that mayor could be black. None of his colleagues believed him until Harold Washington got the Democratic nomination and Monroe got some vindication.

Monroe Anderson: The election was shaping up with Richard Daley and Jane Byrne and they were going to challenge each other and I said-- I, I don't know if you know of Bill Kurtis. He used to be an anchor in Chicago and, anyway, Bill would have this party, pre-Christmas party every year. So, I was-- I went to the party and all the political reporters were sitting at a table and they were having this debate on who was going to win, which would be Richard Daley or Jane Byrne. And I had been covering the black community and I knew that on the west side and the south side, meetings were going on where they wanted to run a black candidate, because the black community put Jane Byrne in office and then she, she stabbed them in the back and went with what she had called the evil cabal, the, the white power structure.

Monroe Anderson: And so they were just, like, fuming and so they were talking about running a black candidate. And, so, these guys are going back and forth, Jane Byrne, Richie, and, you know, and I said, "What if a black person, candidate, ran for mayor?" And the conversation stopped. And it was as if I said, "Well, what if we were invade by Martians?" [LAUGHS]

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS].

Monroe Anderson: And then they looked at me and they shook their heads and they went on with-- They went, they went on with their conversation. So, I wrote an op-ed page piece predicting that the next mayor of Chicago would be black. And I've-- in my theory, the way I analyzed it was, you have a popular candidate in Richie Daley, you have a popular mayor in Jane Byrne, and both were equally popular in the white community, which was 60% of, of the city and then you have-- if you had a black candidate, he could win. And the two I named in my piece were Harold Washington and Roland Burris and, you know, and I said, it's one or the other.

Monroe Anderson: I wrote the piece and it, it sat back in the editorial department for weeks, because there was nothing urgent and, and nothing of importance and then thr-- again through my contacts, I found out that Harold Washington was going to announce his candidacy and that was a big deal. So, I wrote the story on a Friday and because it was too late in, in terms of, of the whole deadline to get it in the Sunday paper, it ran on a Monday, banner, "Washington In Mayor's Race." And I, I go back bec-- because my piece was speculative, the opinion piece, I go back to Jack Fuller. I say, "Jack, you have to run my piece now, because if you don't run it now, it's not gonna be worth anything."

Monroe Anderson: So, on that Monday, my Chicago op-ed column, Chicago could have a black mayor, and my f-- banner story, Washington's in, in the race, which makes me an instant expert on Harold Washington and the race. And, you know, literally I'm, I'm-- people were calling me, radio stations are calling me. I'm on, on the radio. I'm on TV on, on the PBS station and I go off vacation thinking, okay, when I get back, everything will be great. I come back and I'm not assigned to cover the election. There are nine white reporters assigned.

Alex Chambers: Wow.

Monroe Anderson: Men, all men, and I go in and I confront the managing editor about that and he says to me, "Well, we don't make assignments according to race." You know, 'cause I said, I know that this-- the, the city better by far, Chicago better than any reporter on, on its face, on, on the beat, and the lead reporter on the coverage was this guy named David Axelrod who I had known as an intern. I remember when he came in as an intern. And so, anyway, after my prediction comes true, I'm assigned to cover the general election. I get to do that because I was right on everything. I cover it and it was very fiery. The, the day before, a, a-- the Monday before the Tuesday election, I'm on the di-- Day Show, interview by Jane Pauley, and she wants to know, "Well, what if Harold Washington doesn't win tomorrow? Will there be rioting in the streets?" And I knew enough about TV where if one way you want to think about something, what you do is pretend like you didn't hear the question, it didn't come through right.

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS].

Monroe Anderson: And so, I, I, I adjusted in my ear piece and said, I didn't get that, could you repeat it? Which gave me a little time to think about what answer. And, so, she, she repeats the question and I say, well, I would hope that there was no violence, although emotions are running high, bas-- this is, this is not a exact quote, because I--

Alex Chambers: Sure.

Monroe Anderson: But, anyway, I, I didn't denounce it. I didn't say, well, there shouldn't be any vio-- I, I told the truth and the Tribune switchboard lit up from coast to coast with people who had seen the interview and were upset with me and there were some people around the Tribune that were suggesting that I be fired for doing that.

Alex Chambers: Because it-- Because it sounded like you were, to them, that you were encouraging--

Monroe Anderson: I don't know why.

Alex Chambers: You don't know?

Monroe Anderson: They did-- I didn't give the right answer, you know.

Alex Chambers: Wow.

Monroe Anderson: But I was supposed to-- I-- you know, this much I do know, that I, I was supposed to have just said, well, no violence will be happening and that, that-- you know, that sort of thing, because Harold, when he won the primary, Chicago was so overwhelmingly Democratic that whoever won that race, it was just a given, that they would win. But all the white Democrats in Chicago, when Harold won, became Republicans. I mean, overnight. I mean, literally the next day. They, they interviewed this one guy who said he wasn't voting for, for that guy, he, he's gonna vote for a Jewish guy, Epstein. Now, the ca-- the candidate's name was Epton.

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS].

Monroe Anderson: And, and Epton's catchphrase, political phrase was, "Before it's too late." And so--

Alex Chambers: Wow.

Monroe Anderson: And, so Chicago's race was, like, on the cover of Time and News Week, the mayoral race, and I-- you know, and I covered it and then--

Alex Chambers: And you covered the-- not the primary but the general?

Monroe Anderson: The general.

Alex Chambers: Okay.

Monroe Anderson: But I be-- well, because the other problem was, I was everywhere but in my newspaper talking about it.

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS].

Monroe Anderson: I was being interviewed for radio program but I was not in my, my own newspaper.

Alex Chambers: And the Jane Pauley interview was on the eve of the general election?

Monroe Anderson: Yes.

Alex Chambers: Okay.

Monroe Anderson: Yeah. Okay, yes.

Alex Chambers: Yeah, that makes sense. Wow. Well, so then I was interested to hear about what-- sort of, like, looking back at all these different experiences, what are you sort of most glad to have been able to, to do?

Monroe Anderson: Okay, I'm, I'm a columnist. That's what I am. I mean, that's what I was doing here as a student, not a-- it wasn't a column but it was, it was opinion and I wrote an op-ed page column for the Tribune for a year and a half, before I went to News Week. I wrote a, a column for the Sun-Times 12 years ago or so for a year and a half. I wrote a column for the Chicago Defender five or six years ago for a year and a half. And I've done-- I've written for Huff Post, HuffPo, The Root, opinion pieces. There's a new website called The Tribe, which is for black millennials in Chicago. I've written a few pieces for them. I enjoy writing opinions. When I, I did my TV show for eight years and that was fun, but the, the difference between TV and print is that people would come up to me and say, "I really like your show," and I say, "Well, which one did you like?" They just like the show. Whereas when I wrote things, people had an opinion and knew exactly what they liked about it.

Alex Chambers: Right. They remembered the specifics, the thing it was about.

Monroe Anderson: They'd remember the specifics, yeah. Yeah, right, exactly. So, that was-- Although I did four investigations, I was nominated for Pulitzer four times, but for years I didn't mention it at all because as far I was concerned it was like being nominated for an Oscar and not winning any time, you know, so, who cared? But then when they started promoting actors as Oscar-nominated this or-- I said, oh, maybe there's something to that after all.

Alex Chambers: Yeah, right.

Monroe Anderson: Right? [LAUGHS]

Alex Chambers: Exactly, right [LAUGHS]. You got it. That's great. Well, like I said, it's-- there's lots more I would love to ask, but it's been such a pleasure talking.

Monroe Anderson: Oh, well, I--

Alex Chambers: Thank you so much for taking the time.

Monroe Anderson: Alright, now, you're a good interviewer.

Alex Chambers: [LAUGHS] Thanks.

Monroe Anderson: Yeah.

Alex Chambers: You've been listening to Inner States. Do you have a story we need to hear? Have you recorded some really good sound? We want to hear them. Let us know. Go to wfiu.org/innerstates. Speaking of found sound, we've got your quick minute of slow radio coming up. But, first, the credits. Inner States is produced by me, Alex Chambers, with support from Eoban Binder, Mark Chilla, Michael Paskash and Kayte Young. Our executive producer is John Bailey. Special thanks this week to Monroe Anderson. Our theme music is by Amy O. We have additional music from the artists at Universal Production Music.

Alex Chambers: Alright, time to take a slow breath and listen to a place.

Alex Chambers: You've been listening to Boots In Snow, Griffy Lake, Bloomington, Indiana. Until next week, I'm Alex Chambers. Thanks for listening.