Alicia Kozma: It is not revolutionary nor is it helpful to say films from the past are problematic, films from now are problematic. What needs to be considered is, is there a value in watching them?

Alex Chambers: And, if so, how are you going to address those problematic aspects? This week on Inner States, Alicia Kozma has some answers. But first, we'll remind ourselves about the pleasures of old film. That's all coming up, after this.

Alex Chambers: Media in the 20th century feels mostly frictionless, doesn't it? You open an app and stream a pod-cast. I see you there, listener. We'll watch a video. Between YouTube, Spotify and Netflix, you can watch anything and everything all of the time, as the song puts it. I mean, there are still hiccups. Your Internet goes out, HBO says, "Oops, something went wrong." Or, you still have to watch all the commercials on Hulu. But, the only object you're dealing with is the device that's connecting you to the Cloud. No more records with their scratching and skipping... cassettes with their hum... VHS tapes, better rewind that before you go back to the video store... or, that floppy disc... that the computer is still trying to read.

Alex Chambers: So, you heard all that, right? For a brief moment in human history, those were the sounds that accompanied our stories. Before that, other than books, there was no mediation between you and a good yarn, just an actual human relaying a legend or singing a song. If there was a sound accompanying it, it was probably a lute. No friction. Twentieth century media though, lots of friction, lots of sound waves. The individual records and tapes had their own characters. I had this Sesame Street record that would always skip in the same place because it had an actual scratch. I could've got a different copy of the record, if I hadn't been six-years-old, but it was kind of nice to know the sounds of my record.

Alex Chambers: So, why this trip down Memory Lane? Because, today's episode is about the pleasures and perils of old film and movies. Later on we'll hear from our favorite cinema director, Alicia Kozma, about how she thinks about movies that reflect, to put it gently, outdated attitudes about race and gender among other things. But first, we heard about this film series here in Bloomington that got started because of old film, actual old film reels from the basement of the Lilly Library here on the Indiana University Campus. So, we sent Jack Lindner there to find out more.

Male, old movie star, unknown: I wanna see the rest, a month from now this isle of big shots is going to give you what you want.

Male, old movie star, unknown: Too late, they start shooting in the week.

Male, old movie star, unknown: I'm gonna make him an offer he can't refuse.

Male, old movie star, unknown: You talking to me? You talking to me? You talking to me? Well, I'm the only one here.

Jack Lindner: For most of their history, movies were made on 35 mm film. Then, about 15 years ago, smart-phones showed up and they drastically changed how we make and how we watch films.

Female, old movie star, unknown: Toto, I have a feeling we're not in Kansas anymore.

Jack Lindner: Now, almost anyone can make a movie and we're flooded with endless content from YouTube and streaming services. In this technology-driven era of film-making, we can often times take our prior film-making practices for granted. Without 16 and 35 mm film reels, the idea of the motion picture would not exist today and without movie theaters, we would lose that one-of-a-kind environment that has made movie watching a one-of-a-kind experience. While the future of the film industry is exciting, it's important for us to remember the significance of both physical film and the theater-going experience. For Kaleb Allison, one way that we can honor these classic traditions is simply by watching classic films in their traditional format, in a theater, on a big screen, in 35 mm. I met up with him in a coffee shop to talk about it.

Kaleb Allison: The cinema does everything they can to offer it up on film because it does give you a different perspective, a different viewing experience. I keep saying this, but you really can see the history of a print on a screen that makes it a unique object and not just a digital copy that's exactly the same anywhere you watch it at any time. Thirty-five millimeter projecedt prints is a unique experience every time.

Jack Lindner: Kaleb is a PhD candidate in the cinema and media studies program at IU, he's also the curator of the City Lights Film Series, a Bloomington film series that screens movies to the public in their original 16 and 35 mm formats. The series draws from the archives of a film collector named David S. Bradley. As the curator for the series, Kaleb is in charge of selecting three films from the Bradley collection that will be presented during the next season.

Kaleb Allison: Normally we get three films from the Bradley collection, or, that are inspired by the Bradley Collection. Part of the job is just to really understand what's in this collection and how those three films fit together and create a cohesive program that represent the classics of world cinema.

Jack Lindner: The three films chosen for the Spring 2023 season included Robert Breson's "A Man Escaped", Sydney Pollack's "They Shoot Horses, Don't They?" and Alfred Hitchock's 1954 classic, "Rear Window" which was displayed 25 years ago during the Series's first set of screen.

Female, old movie star, unknown: There's nothing to see.

Male, old movie star, unknown: There is something, I have seen it through that window. I've seen bickering and family quarrels, and mysterious trips at nights, and knives and saws, and ropes.

Jack Lindner: The Series was founded in 1997 by IU graduate students, Drew Todd and Eric Beckstrom. I sat down with Eric to take a trip down Memory Lane to explore what inspired him and Drew to create the Series, as well as what they hoped to achieve with it.

Jack Lindner: If someone were to come up to you and ask you what is City Lights, how would you best describe it to them?

Eric Beckstrom: The character of the Series is a little different now, but I would say that at the heart and soul of the Series is to put films in front of people, on a screen, that they might not otherwise ever have the chance to see on the screen, and to move the focus away from such an exclusive emphasis on American cinema and open the door to international screenings. We wanted it to be a community film series and not just something that was merely associated with the Indiana University. That is definitely at the core of the purpose of IU cinema as well, they're not just a university cinema. They try very hard to be a community cinema.

Jack Lindner: Eric's love for film-making and storytelling came at a very young age.

Eric Beckstrom: I grew up in the 70s, shortly after all of the major movie studios had sold the broadcast rights to their catalogs to television. So, I grew up in the 70s watching all these old Hollywood movies from the 30s, 40s, 50s and 60s. I remember Cary Grant, Sidney Poitier, James Stewart, Jean Arthur, Sydney Greenstreet and everybody who was in Casablanca, essentially. It had a huge impact on me and I had a love of storytelling, literally from the time I was three or four. Some of my earliest memories are seeing Rod Serling on the television, so that's probably where it had its root.

Eric Beckstrom: You know, it's interesting because I didn't really have any interaction with 16 mm until City Lights, and so Drew and I were talking about what's happening on campus in terms of film screenings and we learned early on that there wasn't any screening of celluloid consistently, and certainly not world cinema. We just couldn't believe that there wasn't a film series on this campus. It just happens that what we had access to was 16 mm, which taps into the very reason 16 mm came into existence, which was greater accessibility. So, I think City Lights in some ways was one of the last vestiges of tapping into the true purpose of 16 mm.

Jack Lindner: Sixteen millimeter was a monumental innovation when it was first introduced in 1923. Unlike 35 mm, which was only available to film-makers and movie studios the 16 mm camera was portable enough for average people, or anybody who could afford it, to purchase one. This new camera, and the film inside, allowed average people the access to document important events in their lives and to create their own movies from home. Eric and Drew's passion for displaying films in their traditional format proved to be just as popular among Bloomington residents during their first ever screening.

Eric Beckstrom: The first night we filled the place and we were both pleasantly shocked at how many people showed up. There was this palpable enthusiasm and I remember the very first screening, we walked up on stage in Valentine and with absolute no indication that this was going to happen, people just started clapping. I think we were rather bemused, slightly awkward and embarrassed, and I think it really reflected the level of yearning for screenings of films on a screen with an audience that weren't just the stuff you were going to go an see at the local theater downtown.

Jack Lindner: During their time at IU, Eric and Drew helped to grow the Series's audience by providing a tradition movie-going experience. Unlike modern movie theaters where 30 minutes of ads are played before the film, Eric and Drew would play short films from the Gleim Collection before showing the feature films from the Bradley Collection. According to Eric, the film selection was just as arduous as preparing for the actual screening with an audience.

Eric Beckstrom: We would go through and pre-screen films in the basement of Franklin Hall. We would have this very loud, 16 mm, projector next to our head and we would pre-screen them to make sure that they weren't missing large chunks or were just not in a screenable condition. We had to not screen some that were in too rough of a condition and it was very painful to have to pass on a film because of that.

Jack Lindner: Was there a particular film that you remember that you didn't get the chance to screen, but you really wish you could've?

Eric Beckstrom: I do remember one where I think we had pre-screened the searchers, but somehow we missed the fact that the very, very famous last few frames were missing from the print. It was a very famous scene at the end where John Wayne's character walks out onto the porch and you see the door close, and he's out there alone. That little two second scene is one of the most famous scenes from any film from that era, and it was missing. We were just gobsmacked when we screen it. Everything didn't always go off without a hitch.

Jack Lindner: Retelling these stories brought a huge smile to Eric's face. He said that the semesters he spent running the Series with Drew were some of his favorite moments from his time at IU.

Eric Beckstrom: It is one of our core memories of that time. I can speak on Drew's behalf and say it is, like mine, one of his favorite memories of all time. It was extremely gratifying. I think we both felt like we were doing something for the community, for the campus. Frankly, self-indulgent in a way because we had access to these prints and seeing an audience sit together and experience that film together, being a part of that opportunity was just extraordinarily gratifying.

Jack Lindner: I mentioned earlier that City Lights gets a lot of its films from the David S. Bradley Film Collection. That collection is housed at the Lilly Library, which is Indiana University's special collections library. The Bradley Collection sits alongside material from some of film history's greats, like Orson Wells, John Ford and film critic, Pauline Kael. You've probably heard of them, but maybe you haven't heard of David S. Bradley, so how did his collection draw so much attention from people across the film industry.

Rachael Stoeltje: My name is Rachael Stoeltje, I am the founding director of IU's library's movie image archive which we founded in 2010 and we're doing a lot of work right now trying to advocate for current film-makers to preserve their own films and getting information out there about the fragility of digital formats.

Jack Lindner: Rachael Stoeltje is a film-archivist who has processed the majority of the motion picture film collections at Lilly Library. She has spent five years researching, processing and restoring the films in the Bradley Collection after it first arrived at the library in 1987. In that time, her work led to her learning more about Bradley's life, career and the collection he worked so hard to preserve.

Rachael Stoeltje: I spent four or fives with that and I feel like you really get to know a person from their collection.

Jack Lindner: Bradley was born and grew up in Winnetka, Illinois, just north of Chicago. It was in the Windy City that Bradley developed his passion for film-making and it was in this city where he began his career alongside a future Hollywood legend.

Rachael Stoeltje: David Bradley's interesting. He was a student at Northwestern in Chicago and he made his first early films, I think 1941 was "Peer Gynt" which he made with a really young Charlton Heston who really had to step up. I think he was 17 maybe at the time.

Jack Lindner: "Peer Gynt" was Heston's screen acting debut and it's based on the Henrik Ibsen play of the same name. Bradley would later team-up with Heston again in 1950 for his film adaptation of Julius Caesar with Heston playing the role of Mark Antony. Heston would go on to become one of Hollywood's greatest leading men thanks to his roles in biblical epics such as "Moses and the Ten Commandments" and Judah in "Ben-Hur". Bradley's career on the other hand was starting to fizzle thanks to some questionable choices.

Rachael Stoeltje: He made a lot of B films, "They Saved Hitler's Brain".

Jack Lindner: You heard her right. In 1968, the same year that his friend, Charlton Heston starred in "Planet of the Apes", David Bradley released his latest film titled, "They Saved Hitler's Brain". A film with that kind of title was about as successful as one might expect.

Rachael Stoeltje: I think "They Saved Hitler's Brain" has made it to the worst movies of all time list before. It is astonishing, they carry around Hitler's head in a box but he's talking all the time.

Jack Lindner: After multiple box office failures, Bradley called it quits on film-making but rather than completely leaving the industry, he turned to another passion to keep his love for movies alive, collecting. Thanks to the connections he made in the industry, Bradley's archive quickly began to grow into a magnificent assortment of 16 and 35 mm film reels, production photos, letters and other items across multiple eras of film history.

Rachael Stoeltje: There are about 26 hundred titles. It works out to be about 58 hundred reels of film, so some titles have multiple reels. So, about 26, 27 hundred I think. So if you started to scope it out, chronologically it has the very first films, so 1894 and around the world. So there's a whole series of early French silent films or Russian films. It's a comprehensive, lovely history of film from 1894. I feel like the very last film they have is maybe "Kramer vs. Kramer", so in the early 80s.

Male, old movie star, unknown: Where's Billy?

Female, old movie star, unknown: I'm not taking him with me. I'm no good for him.

Jack Lindner: As Rachael said, part of what made the Bradley Collection so unique was the variety of 16 and 35 mm films that he archived, including a few early silent films that, as far as they know, do not exist anywhere else in the world.

Rachael Stoeltje: I've narrowed it down, there are just two films in the collection that truly don't exist elsewhere. So I'm working on the restoration of that one. For years I thought there were four titles that didn't exist elsewhere, but about five years ago I spent a lot more time really diving into it and I did find Academy Film archive had recently found one of them. So we have spent the last three years working on "Sky High Corral" which is a silent Western that I think will be fun for us to screen and share with the world.

Jack Lindner: Before Bradley's death in 1997, he was in contact with multiple film organizations to decide who he wanted to Will his collection to after he passed.

Rachael Stoeltje: He had willed the collection to a lot of different organizations. He would get upset with the organizations at Northwestern, I think UCLA, maybe the Academy film archive and then he would take them out of his Will. So he willed them to the Lilly probably to be with Orson Wells, John Ford and some of the greats. Before it actually landed here, the Academy film archive asked if they could just store it for us and process it and we could retrieve film prints. This is how unique and valuable this was perceived. But they truly have some of the most historically important film collections from the greats, so Orson Wells, John Ford, Pauline Kael's papers. They have such rich, amazing bodies of work but I would guess that was part of his draw.

Alex Chambers: Right, it's time for a break. You're listing to producer, Jack Lindner's story about the pleasures of old film. When we come back, Jack heads into the archives where he finds himself transported back to the set of "Metropolis". This is Inner States, stick around.

Alex Chambers: Welcome back to Inner States, I'm Alex Chambers and we're getting a tour with producer Jack Lindner of the archives of David Bradley. Bradley was a film-maker whose career was among the less successful of the mid-20th century film-makers. But once he accepted that, he focused his energy on collecting. I'll let Jack take it from here.

Jack Lindner: Because this story is about the importance of 16 and 35 mm, I wanted to examine the collection for myself to get a better understanding of both the archives and the man who brought it together. I set up a meeting with Erika Dowell, the associate director and curator of modern books and manuscripts at Lilly Library. Erika was kind enough to bring out a few boxes from the Bradley Collection to let me examine.

Erika Dowell: I just requested two boxes of materials from the David Bradley papers. The whole collection includes 124 boxes, that includes all kinds of paper documents, photographs but also film elements.

Jack Lindner: We couldn't get access to any physical film reels from the collection, but Erika came prepared with other items that were just as fascinating.

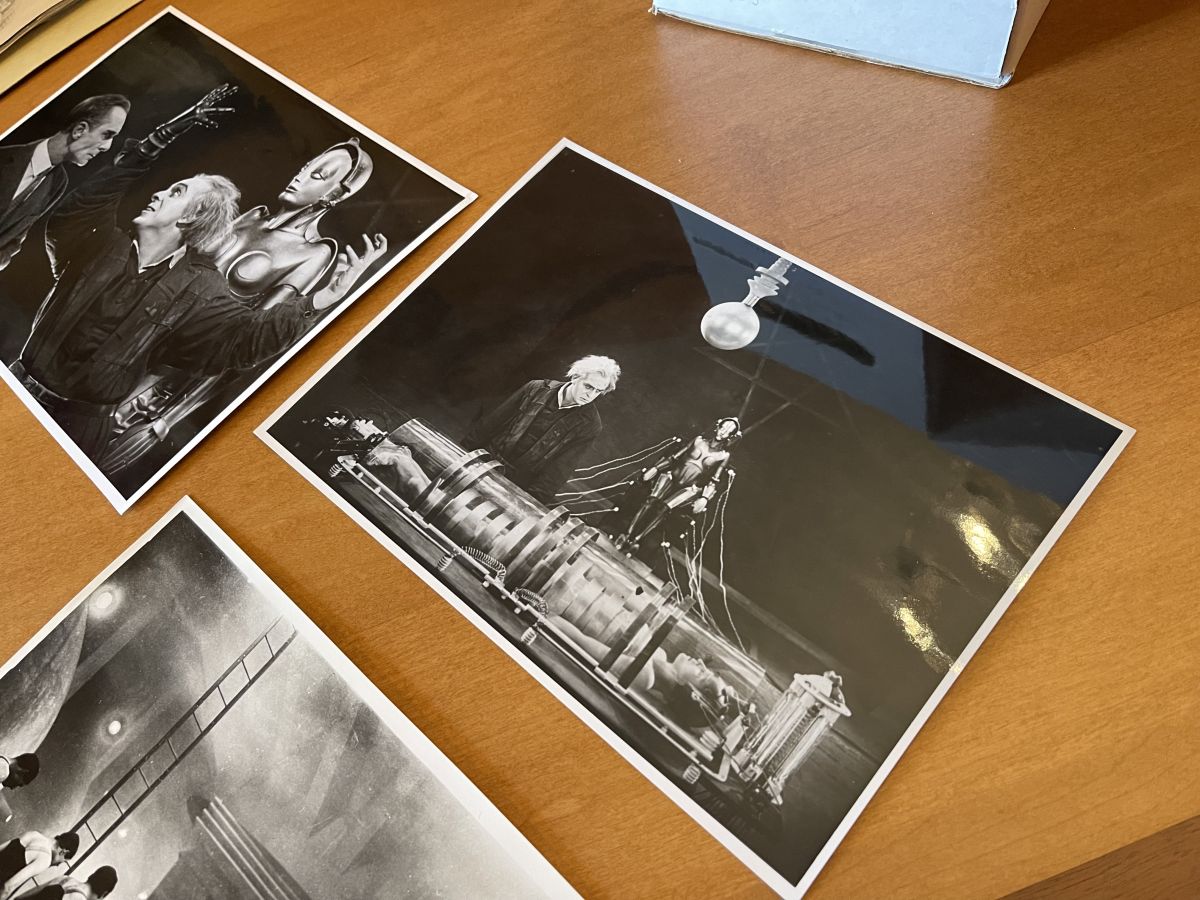

Erika Dowell: The photography collection includes both photographs from films that David Bradley made. For instance, this folder which has stills from "Peer Gynt", promotional posters and plenty of stills from the actual action of the film. It also includes film stills that he collected about other types of films. For instance, here's the famous "Metropolis", so those are clippings and programs, things like that. And then here in the second folder from "Metropolis", again, a whole bunch of film stills that it's likely he collected from various places. You can see that some of these are...

Jack Lindner: As I looked at all these photographs from the archives, it felt like I was being transported back to 1927 to the set of "Metropolis". The stills captured many iconic moments from the film, and for me, they really put into perspective the countless hours that must have gone into creating such a technologically advanced world for this film. Another photo we found showed the movies two cinematographers, Guther Rintel and Karl Freund, with two giant Mitchell cameras on either side of them. In between both men is fellow cinematographer, Charles Rusher. Karl Freund would go on to be the cinematographer for the original "Dracula" and the cinematographer for over 150 episodes of "I Love Lucy". Rusher would go on to win two Academy Awards for his work on films like "Sunrise" and "The Yearling". Rusher didn't work on the set of "Metropolis" but seeing him in this photo leads me to believe that these three had a chance to help make each other better, rather than simply competing against each other. In the competitive world that is the film industry, there was something comforting about seeing these three legends of their craft work together.

Erika Dowell: This is one of example of correspondence with a colleague from the 50s. You can see here's a letter that was written to David Bradley on a yellow legal pad and then we also have some carbons of the letters that David Bradley wrote back, which is always nice to have.

Jack Lindner: During his years directing B films in the 50s and 60s, Bradley worked as a junior director at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. A lot of the letters from the folder came from stationery with the same MGM letterhead at the top.

Erika Dowell: I'm just going to say that I think these folders are interesting. They're about his "Peer Gynt" film but they're quite a long time after it was made, so there's a whole bunch of different documents that relate him getting the film transferred, making copies of it, and then I believe that a lot of this documents getting it screened in various places. You could do a whole biography of the after-life of that film using this collection.

Jack Lindner: One of my favorite items I saw in the collection was a postcard sent to Bradley that was written from Madrid. The note attached is written from someone name Art, but it's not clear how he was directly connected to Bradley. If you look closely, you can see that it's actually a home-made postcard written on the back of a photograph of one of Bradley's close friends. That friend in question? You guessed it, Charlton Heston.

Erika Dowell: It's someone who's helping him get films. You can see he stopped in Paris en-route and got the last underscored a copy of Brunells and the one last H. Lloyd, Harold Lloyd, no more 16 mm from film office in future, only eight mm. new list has almost all 16 mm crossed out. Found same in German camera stores but only Chaplin mutual stills available on 16 mm with German titles. Thought you would get a kick out of this postcard. Which is off Charlton Heston. Yes, so this interesting and we could probably figure out who Art was, but it seems that someone who's helping him with sourcing films to collect from different places in Europe, because he mentions being in Paris. This is sent from Madrid and he also mentions looking in German camera stores.

Jack Lindner: The fact that Bradley possibly had someone collecting precious items for him from across the world, just goes to show how dedicated he was to archiving film history. It's almost as though Bradley knew these collections would be studied one day, like he knew these simple items would become priceless pieces of cinema history. Erika agrees with that notion, in her eyes, by acknowledging these pieces of our history, she believes that it can lead to a better understanding of who these individuals were.

Erika Dowell: That's the kind of great stuff that an archival collection can hold, right? You can take just one folder and it's documents that show you little glimpses of the relationship between two people and then allows one to go and try to fill in all the blanks. Like, who were these people? What was this project? What do these letters tell me about their relationship and about the thing that they were trying to do together? Again, it's just one little folder in a collection that has more than a hundred boxes.

Jack Lindner: 2023 marks 100 years since the invention of 16 mm film. In a way, the introduction of 16 mm prefigures the introduction of smart-phones since it allowed more people access to record the world around them, essentially turning everyone into a film-maker. For Eric, these technological advancements have all but rendered physical film as obsolete.

Eric Beckstrom: I think in some ways it's not relevant. I don't know if very many people want to say that but in some ways it's completely irrelevant. It gave broader access and I think that is important historically, and I think it's more important for academics, for historians and for cineophiles than it is for your broader audience. Film-makers don't touch film these days if they're making digital film. Now it's a conscious decision, am I going to use celluloid and it's this specialized thing.

Jack Lindner: Although the technological advancements of the film industry are very exciting, Rachael argues that we must not lose sight of how we got to where we are today. In her opinion, 16 and 35 mm film play vital roles in telling our stories.

Rachael Stoeltje: I think motion picture film around the world, our global film heritage tells such a remarkably strong story of who we are, what we value and where our histories are. I think it's just a really relevant way to preserve our history and it's the only one that's a little over a century old, so film is not really that old but I think most of us take for granted since we walk around recording. Every single person can record our lives now.

Jack Lindner: Unlike a digital format, physical film reels are ones that can be restored and updated for future generations, and it's this crucial aspect of the film preservation process that Rachael worries we will be missing out on in the future.

Rachael Stoeltje: About ten years ago there was a big, comprehensive search about US American silent films and how many are lost. So, about 85 percent of our motion picture film heritage from the silent era has gone, completely gone. This big report that was done even mentioned the Bradley Collection. I only worry about digital for the future, that we're going to lose a lot of things. Digital formats are just so much more fragile. I will almost put money on it that 50 years from now, teenagers from the future will not be able to see all the films we made today. I've started to say to everybody just out it back to film if you want it to be here in a hundred years. That's the way to go. I will also say motion picture film is historically a perfect preservation format. So, if stored properly, it will be around for hundreds of years.

Jack Lindner: The theater-going experience has also experienced a major downfall due in large part to streaming services like Netflix, Hulu and Disney+. While wider access to movies is an exciting breakthrough, the rise of the streaming industry is costing audiences the opportunity to view films in their intended environment. A theater can immerse the audience in the world of the film, this in turn can help audiences better understand where characters on-screen are coming from and it can make the experience that much more enjoyable. During his time with City Lights, Eric had a first-hand look at how a theater can affect the movie-watching experience.

Eric Beckstrom: When we were there, we were always in the back and you could see people just absorbed in the movie and to watch people grow silent during serious or exciting moments, and to laugh at other moments was just extraordinarily gratifying.

Rachael Stoeltje: I think the big screen is really perfect for most of these experiences. We had a horror film being screened in our screen room not too long ago and the undergraduates were like, "Oh, I've seen this before." And then they were terrified at the end of it.

Jack Lindner: I completely understand what Rachael is saying here. In February, I attended City Lights's screening of "Rear Window" to get the experience of watching a film on 35 mm first hand, and also because I'm a big fan of Hitchcock's work. Although I had already seen the film, being in that environment completely changed the entire experience. I caught my heart racing multiple times throughout some of the film's most suspensible scenes. Seeing the original aspect ratio and looking at all the little blemishes in the film made me feel like I was audience member back when the movie was first released. The print they used for this screening had so many unique qualities, like little dust spots and scratches that you could see up on the screen. The audio for this specific print had odd clicks and popping sounds that you could hear as the film was going through the reels, and if you paid close attention, you could even catch the cue marks up in the corner of the screen which indicates to the projectionist that a reel change is coming.

Eric Beckstrom: It was a very good print, but it's imperfect and that's part of what adds to the specialness. Digital is actually too perfect in some ways.

Jack Lindner: Whenever the debate comes up, I'm always on the side of keeping movie theaters alive. To me, there's no other movie watching experience like it and watching 35 mm film gives us a look into our history unlike any other format. It's blemishes are what make it unique, and when you combine the two together, what you get is the ultimate form of movie magic.

Jack Lindner: For Inner States, I'm Jack Lindner. In case I don't see you, good afternoon, good evening and good night.

Alex Chambers: Jack was an intern at Inner States this past Spring. Along with producing this story, he did a great job covering the local theater scene. Thanks Jack, for all your great work. Okay, it's time for another break. When we come back we'll talk about how to approach those old movies that you might still like or value, even though they've got some problematic assumptions in them like, you know, casual racism or homophobia. What do you do? Stay tuned, that's what.

Alex Chambers: Inner States, Alex Chambers. So, as my kids have gotten older, there are more and more movies I want to show them that I love but, a lot of them have some pretty sketchy and unexamined attitudes that I'd like not to reinforce. So, I called in Alicia Kozma, director of the IU cinema, for some advice.

Alex Chambers: One of the ways I got started was "Back to the Future". My eight-year-old wanted to watch it because I'd been talking about how much I liked it.

Alicia Kozma: Yeah.

Alex Chambers: We watched it and I wasn't surprised by those moments that are difficult because I remembered. But, thinking about movies that depict race in bad ways or controlling or abusive relationships in ways that aren't critical or ironic of those.

Alicia Kozma: Yeah, yeah.

Alex Chambers: It's something that you have to deal with pretty regularly at the cinema. What are we supposed to do with that? Alicia Kozma, director of the cinema, give us your wisdom.

Alicia Kozma: Well, I'll say it's really difficult in putting any hard and fast boundaries around what we do with films that have images, content, actions or themes that today we would be shocked to see, as being passed off as a normal and natural structure of the film. So we're thinking about films that are not being critical of something like racism or a sexual assault, or domestic abuse. They are simply interwoven into the narrative as normal, right? Or even something like homophobia. Every movie from the 80s has the most casual homophobia interlaced and intertwined in it, and it is just part of the culture. It can be shocking when we sit down and we watch these films from the past, and unfortunately the past is maybe more recent than I want it to be. So films that I loved as a kid, especially in the 80s, I sit down and I watch them and it's just like, "Oh, I don't remember this." Or, I don't remember experiencing it in this way because of course I was a kid and it was just part of the culture then so it didn't impact me in the same way that it does now, being a thinking, conscious, critical adult.

Alicia Kozma: The most important thing, when we deal with films like this, is determining the value in screening it. It is not revolutionary nor is it helpful to say films from the past are problematic. Films from now are problematic. What needs to be considered is, is there a value in watching them and does that value, 1) outweigh or override some of the more difficult thematics or contents in the film? And if it does, how then are we addressing those difficult thematics and content in the film? Because the worst thing you can possibly do is just say, "Oh, there's some bad stuff in here." Throw it up on screen and call it a day. What you want to do is engage with that material and think about why it's there, why it still matters that we're watching this film and how are we going to talk about and work through these issues.

Alicia Kozma: There has to be, always, a way for us to go and reach into our cinematic past, and a way for us to reach into our cultural past and engage with that. It's what makes us who we are. It's what makes our culture and our cinema what it is today. So it's not helpful to just cancel movies that are problematic in some way, shape or form, nor is it helpful to skip over what's in there. There has to be a type of engagement with it. One of the ways that we handle this at this cinema is that we have introductions before all of our films and we make a really concerted and careful effort to call out those themes, those actions, those images, those contexts, that to us in 2023 raise red flags and we talk about them. We don't talk about them in a way that's shaming nor in a way that's endorsing, but it is a reality of the film and is going to be a reality of the people when they're watching the film, right?

Alicia Kozma: So, you want to engage with that, foster a conversation around it and talk about does this play a role in the film? Is this coming simply from the cultural zeitgeist at the time that the film was being made? Why is this in here and why does it matter that we're still watching this film despite the fact that it has this type of content? I think a lot of this, quite frankly it is a conaughtical film from the silent era, D.W. Griffith's, "Birth of a Nation". As a film student, I was subjected, and I say subjected because it is three and a half hours long, to watching that movie at least two to three different times in different classes I was in. But they were all for good reasons, right? It was all because it is a critical piece of film history and it exists in film history in a lot of different ways, and it has influenced a lot of different things. You film students, you need to know that. But you also then need to recognize it is a film that celebrates the Ku Klux Klan.

Alicia Kozma: So, you have to be able to do both of those things at once. I feel like increasingly it's becoming harder for people to hold two things in their head at the same time, particularly when they're contradictory, but that's why we do the intellectual work of cinema studies and that's why we bring that type of perspective into the programming that we do at the cinema. Now, "Birth of a Nation" is not a film that's often shown in cinemas today because it's a three-hour silent epic that celebrates the Ku Klux Klan, but we have shown it at this cinema specifically because the Black Film Center and Archive here on campus was doing an event around it. Talking about the legacy of it. So you bring in the experts, you bring in those people who can not just say this movie is damaging and full of racist stereotypes. But you can say here's the impact that it had. Here's what we've had to undo because of the mythology of "Birth of a Nation", because of the way it's been incorporated into cinema history, because of how it was thought about often uncritically.

Alicia Kozma: Also, screenings like that also help to repair some of the mythology around the films. It's not like a three-hour movie celebrating the Ku Klux Klan was released into the world and everyone was like, "Oh, what a great movie." There were protests, people didn't like it. There were anti-racist then, just like there's anti-racist now. So it helps to fill out the story and bring the film out of the history book and into the real-life context of what it means to be a piece of moving image in culture. It is always going to have different forces that are interacting with it, and so for an event like that, it's really important to bring those things up because demystifying a piece of cinema history that has been so lauded for some of the technological inventions that Griffith's did on that film, which are still used today like dolly shots for example. There's dolly shots in every movie. One of the first films with dolly shots.

Alicia Kozma: You have to see the 360 degrees of the thing and so while things like "Birth of a Nation" outside of the context I've described are not normally shown in cinemas, lots of movies from when I was a kid, the 80s, are.

Alex Chambers: You mean by cinemas just for entertainment?

Alicia Kozma: Just for entertainment purposes, absolutely. Like, retro Tuesdays or flashback Fridays, if you look at any of those, they're 80s movies.

Alex Chambers: Right totally.

Alicia Kozma: They're usually the same 80s movie suspects over and over again, and I have to say, when you're a programmer there's always something in the back of your head, especially when you remember that movie nostalgically, that you need to stop and check yourself. At the cinema we call is doing a new eyes rewatch. Like, let me watch this with my new eyes. I remember at a previous cinema I worked at several years ago, we did this special late-night event where we were showing "Back to the Future" and we got a DeLorean and we had an under-the-sea prom in the lobby, and the theater was packed. We were watching "Back to the Future" and I'm halfway through the movie and at that point I hadn't seen the movie in 15 years. I'm watching it and I'm like, "Oh, oh, we should've rewatched this before we put it up on screen."

Alex Chambers: Because it's so imbued with all the nostalgia?

Alicia Kozma: Yes, because when you're a kid watching the film for the first time, especially in the context of culture in the 1980s, casual homophobia, casual sexual harassment, casual racism was just part of the milieu at that time and it is a part of "Back to the Future", but it was nothing that was something that stood out when I was ten watching that movie.

Alex Chambers: But I think there's another thing that you were getting at with the watching it with new eyes.

Alicia Kozma: With new eyes, yes.

Alex Chambers: It sounded like there was another question too, which was not just being able to notice all those things that we've been talking about, but also does this movie have anything else going on that's worth... does it hold up as a movie?

Alicia Kozma: Does it hold up? And so that's the question we say. Does it hold up? That is actually the exact question. In the Fall semester we did a study-break movie marathon where just showed movies for 12 hours for free so students could take a break from studying for finals, and come in to watch movies. Brittany Friesner, who's the managing director of the cinema, and I got really excited about showing this movie called "Summer School" because the theme of the marathon was movies about the last days of school. "Summer School" is a movie from 1985 and we both remembered it very fondly, but it is a movie from 1985 about a bunch of kids who the movie frames as "failures" and sticks them in summer school with Mark Harmon who's like a gym coach turned summer school teacher. We both said, "One of us has to watch this." And so, we got the blue-ray and Brittany took it home. She watched it and she came into work the next day and she said, "It holds up. It holds up surprisingly well and is way more progressive than I remember it being."

Alex Chambers: Wow.

Alicia Kozma: So I rewatched it and I was like, "You're absolutely right, it holds up." There's a value in showing this movie, especially for this film because this was really surprising to me. A film that I don't think either of us was expecting to hold up, but neither of us expected that it was going to be as progressive as it actually was. So, I was like, "This is not the type of 80s movie that's normally shown in the nostalgic category and I think it's really important that we do that because what we don't want to get into the habit of is generalizing all film that comes out at a certain point, of all being the same way." We showed it, and people really like it and almost no-one had heard of it, which is fine. They were into it and it was really unexpected.

Alicia Kozma: So yes, watching something with new eyes, what don't I remember about this film? What is important about this film? Is it important enough that we want to be showing it today and how are we contextualizing? How are we framing it? Like, what is the need for this and how are we communicating that need?

Alex Chambers: Okay, so that all makes sense in terms of programming for the cinema. There's a part of me that wants to ask this stuff as a parent. Part of the question I'm interested in is, "Summer School" surprised you by holding up in a political way better than you expected. What about a movie that you have nostalgia for, you'd watch it with new eyes, but you're not necessarily looking to see where it lands, progressive versus retrograde or whatever. But does the story still hold up? Is it still a good movie even if it has these elements? Do I want to show it? Do I want to show it to my kids, Alicia?

Alicia Kozma: To my kids? Yes. It's a hard question, but I think that it's a question that parents ask themselves about most things.

Alex Chambers: Of course.

Alicia Kozma: I will say I regularly get calls from my sister. I have a 12-year-old niece and I get regularly get calls from my sister saying, "Can Vivianna watch X?" She recently called me and said, "Can Vivianna watch "Outer Banks"?" and I said, "Absolutely not." Which is a current show that is airing on Netflix. I said, "Absolutely not. Maybe when she's 16 she can watch "Outer Banks"." Then she called me not that long ago and said, "Can Vivianna watch "Clue"?" I said, "Yeah, actually she can." I think she can watch it with her, but yes, 100 percent she can.

Alex Chambers: There are some conversations to be had.

Alicia Kozma: There's some conversations to be had but they're good conversations.

Alex Chambers: Yes, right, right.

Alicia Kozma: So, that's what I think is the most important thing, you want to be engaging in the material like all good parents do anyway. Engage with the material that you're consuming with your children. But, I do think it's important to share those things with your kids because they're part of who you are as a cultural person and I know no-one references movies as much as I do, but even if you reference them or talk about them at some point, your kids are going to be interested in what they are. So, I think it's an important thing to do. That's part of your cultural persona and you're passing that down to your kids whether you know it or not and so you might as well bring them into the fold and talk to them about why this mattered to you, why you want to share it with them. Have those conversations with them, but it also is like with anything that comes down with parenting, it's kid dependent. It's totally kid dependent. But I wouldn't ever necessarily exclude your kids from participating in the stuff that you loved when you were a kid because that helps them connect with you more and it also then brings new traditions into families too.

Alicia Kozma: If they were anything like me, I was not allowed to watch tons of stuff when I was younger but I watched it anyway. I found ways to watch it anyway, and you know what? A lot of that stuff would've been better if I had listened to my parents and watched it with them, or waited to watch it when I was a little older. I didn't need to watch "A Clockwork Orange" when I was 11, but I did and I shouldn't have. I should've watched it with an adult. So it's good. I think it's a really great way of bringing filmies together but also making kids feel like they're part of the cultural conversation. That they can be as engaged with and thoughtful about the culture that they consume, that adults can and that actually, we want them to be. They need to learn that earlier rather than later.

Alex Chambers: Yes, and giving them practice having those conversations even if at the beginning of those conversations... I'm remembering friends of mine when we were growing up in the 80s and 90s, their mom would say to them, "What is this commercial about, kids?" And their answer would always have to be, "Sex, mom." So even the critique can become a little rogue sometimes. But it was still also valuable.

Alicia Kozma: So, tell your kids I said they can watch whatever they want as long as they watch it with you.

Alex Chambers: Cool. Do you have anything else you want to add?

Alicia Kozma: I would just say don't be afraid of going back and revisiting the culture of your past, honestly, and don't be afraid of finding ways to... If it was meaningful for you, to bring it into your contemporary life. We've all made dumb cultural mistakes, but those mistakes are part of who we are now, as living, breathing, critical beings. So allowing kids, even young adults who are in a space where they're making their own choices, usually totally outside of any adults eyes or approval, help them figure out what works for them and what doesn't. Where they want to be and where they don't. What they want to be watching and what they don't. It just gives them a healthier relationship with what is, quite frankly, an ever present media landscape. They can't escape it, so I think the most beneficial thing to do is for us to help them to learn how to work with it and how to make it work for them.

Alex Chambers: Beautiful.

Alicia Kozma: Yay!

Alex Chambers: Thanks, Alicia.

Alicia Kozma: You're welcome.

Alex Chambers: Alicia Kozma, she runs the IU cinema and her book, "The Cinema of Stephanie Rothman" came out in 2022. You can check out my full-length conversation with Alicia, where we discuss Stephanie Rothman's radical film-making in the Inner States archives.

Alex Chambers: You've been listening to Inner States for WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana. If you have a story for us or you've got some sound we should hear, let us know at WFIU.org/interstates. Okay, we've got your quick moment of slow radio coming up, but first the credits. Inner States is produced and edited by me, Alex Chambers, with support from Violet Baron, Eoban Binder, Mark Chilla, Avi Forrest, Luanne Johnson, Sam Sheminar, Payton Whaley, and Kayte Young. Our Executive Producer is John Bailey. Our theme song is by Amy Oelsner and Justin Vollmar. Alright, time for some found sound.

Alex Chambers: That was, as far as I could tell, the creaking of trees recorded at Red River Gorge, mid-December 2022. Until next week, I'm Alex Chambers. Thanks as always for listening.