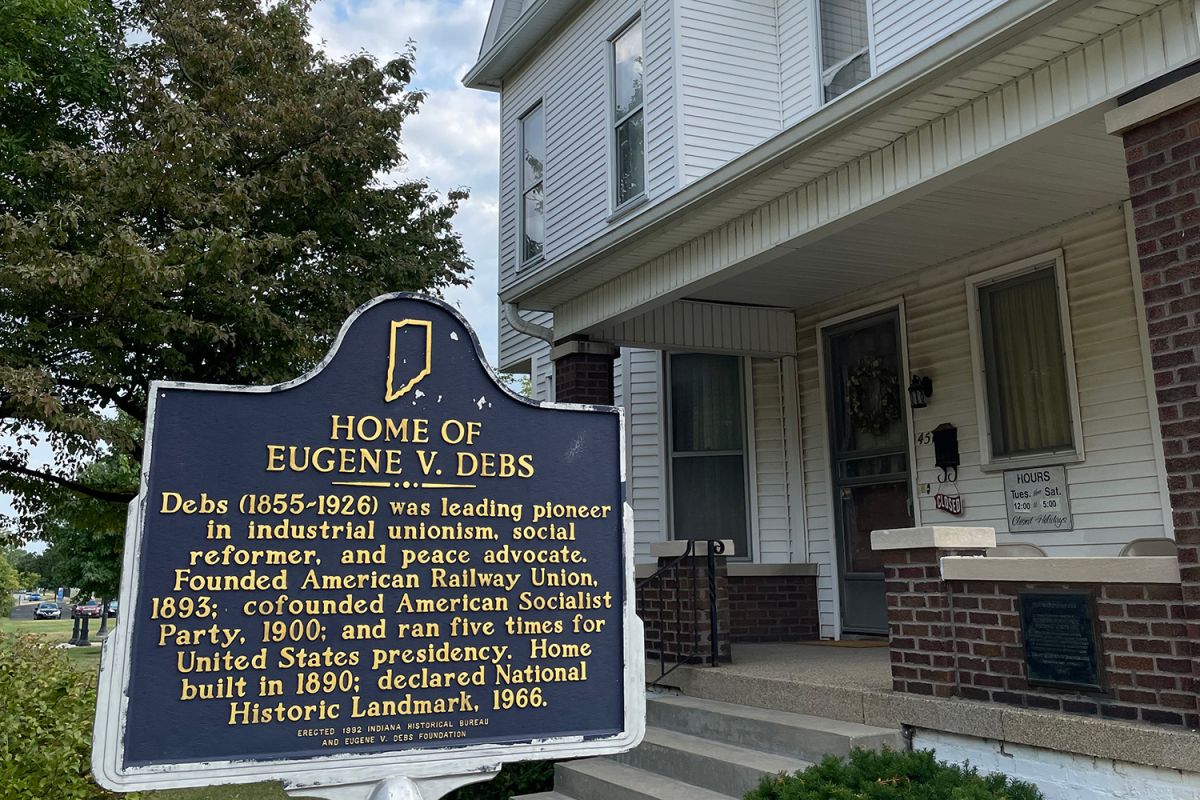

Alex Chambers: If you're wondering which house in Terre Haute, Indiana has the most followers on Twitter, I think it's safe to say it's the one on North Eighth Street, surrounded by Indiana State University parking lots, just south of the marching bands practice fields. It's the Eugene V. Debs Museum. Long before it was a museum, it was the home of Eugene V. and Kate Debs.

Alex Chambers: A hundred years ago, Eugene Debs was the most famous socialist in the US. He was the Presidential candidate for the Socialist Party's first five attempts, which suggests how well he did on that front. The last time he ran he was in prison. He got six percent of the vote. At the time, it seemed not bad for a convict. Now, it's a museum, dedicated to the memory of the most popular American socialist before Bernie Sanders and, along with Larry Bird, who got his start playing basketball for ISU, one of Terre Haute's most famous sons. I have to say though, the house's on-line presence does raise some questions. How is a Twitter account of a small mid-western museum devoted to a figure who died a century ago doing as well as it is? Who's behind this Twitter account? If the person who runs it is also the director of the museum, and she got the job at a college and she's gone there happily, nay devotedly, for eight years now, what makes you devote your livelihood to the memory of a guy who died a century ago, especially if he's not a religious figure?

Alex Chambers: How long does it take to get to Terre Haute? It turns out it's about an hour and a quarter if you live in Bloomington. I should have checked that before I left. Luckily, Allison Deurk, who does indeed run the museum and the slightly less important in the scheme of things Twitter account, is also running late.

Alex Chambers: Hello. Good morning.

Allison Duerk: Good morning.

Alex Chambers: I'm going to turn it over to Allison in just a second here, but I do want to note that I think it's a measure of her devotion to Debs and the museum that she's spoke in the first person plural when she apologized for being late.

Allison Duerk: Thank you so much for your patience. I hope we didn't keep you waiting.

Alex Chambers: No, no. Not at all.

Allison Duerk: Oh my gosh!

Alex Chambers: Okay, after the break, we'll walk through Terre Haute, learn what got Allison hooked on Debs and even learn a little bit about Debs himself along the way. And we'll come very close to stopping at Jimmy John's for sandwiches. Stay with us.

Alex Chambers: When Allison came to Terre Haute for college, she didn't expect to get so embedded in the place, its present and its past.

Allison Duerk: All these different places, like where Gene grows up, where their store was, where Kate's family ran the business, like, I spent, kind of some time there. Like some real time, honestly.

Alex Chambers: Right, right, exactly.

Allison Duerk: So, I thought we would, like, walk down Eighth Street.

Alex Chambers: Okay.

Allison Duerk: We can talk about the other houses on the block. It only happened because of Debs basically, Like 120 years ago, he and hundreds of other people got together in Chicago to co-found the one big union, the Industrial Workers of the World-- I'm wearing their shirt right now-- for the whole working class. No matter what your job is, what you look like, where you're from, if you are of the working class, if you're not a boss, you can join this union. Even if you don't technically have a job, or if you're a migrant worker, if you're an itinerant worker, whatever, and students too. Like that means students as well, like we are workers.

Alex Chambers: What is your sense of what Debs means in the community of Terre Haute at this point?

Allison Duerk: Yeah, it's still a mixed bag,honestly. Like, there are great local supporters who show up for everything we ask them to. There are still people who never thought this house should have been kept as a museum, like I see it mostly on social media. I don't really see it in person. And like, people who will comment that the Debs house should have been torn down 60 years ago or whatever. People who think that Debs was, what's the word I want to use? Well okay, in the big picture there is this narrative out there in the atmosphere that, like, Terre Haute de-industrialized and declined because of its supposedly violent labor history and, like, we did have a general strike. We did have and still have unions, but that's not really unique to Terre Haute either. People like to compare Sub Bloomingtonand, like, well why didn't we become this fabulous well resourced community that Bloomington did? And I'm like well, we don't have a big ten school either. Like that's one thing.

Alex Chambers: Right.

Allison Duerk: At the end of the day, like, our economy was built around industry that left for pursuit of profit. And I'm not the first one to say this, but no union ever shut down a mine or closed a factory, or fired its workers. Like, that's not how that works, right?

Alex Chambers: But for unions to get enough power that people would even think to blame them for lost jobs, something had to happen. You needed people with a vision for what a union could accomplish. In the 19th century, Terra Haute was gathering the ingredients to produce a person like that.

Allison Duerk: Terre Haute gets on the map because of Fort Harrison. I mean, the word Terre, or words Terre Haute come from French for high ground, which refers to an elevated site along the Wabash River, that was the site of Fort Harrison, an important staging ground in the battle of Tippecanoe. Gene's parents, Daniel and Daisy Debs, were French immigrants from Colmar, Alsace. They came over in the late 1840s and found about 5,000 German immigrants here in Terre Haute in the 1850s.

Allison Duerk: We're also beginning to industrialize and Terre Haute also gets on the map as a transportation hub. The river, the national road and the railroads become the three factors that make Terre Haute the transportation hub it would become.

Allison Duerk: For a brief period in the later part of the 19th century, the population roughly doubles by the decade. So, one of these classic mid-western boom towns is really what Daniel and Daisy find themselves in when they arrive and build their family in Terre Haute, Indiana.

Alex Chambers: Terre Haute was not so much a boom town when Allison arrived in the early 21st century.

Allison Duerk: I came to Terre Haute for music education, like band stuff. I wanted to be a band director and laid my arms around for a long time and a lot of people around me, family members, were encouraging me to consider a different route because education-- this is 2012, 2013, like it was a rough scene for sure. So, I got really interested in, like, the policy side of that. I was a social work major for a semester and had to take a seat in local government class, and that's really what, like, got me into political science as my major.

Alex Chambers: How did the state and local government class, in particular, turn you onto all this?

Allison Duerk: It was a way to kind of connect, like, my individual maybe, like, political views or experiences to systems, if that makes sense, and like, how we fight for policy change but also like, how unresponsive our systems are too.

Allison Duerk: I was doing a research job for an awesome historian ISU, Lisa Phillips, who's like a board officer for us too, and as part of that work, she had me do tours at the house one night a week, just as a student, to keep it open while they were between staff. And that was, like, as I was joining the IWW, the Industrial Workers of the World, and, like I mentioned, like, going into my first union training and it all kind of fell into pace. And right when it was time to graduate, they were putting out their job posting and so it was, like, time to apply for the real gig and it worked out.

Alex Chambers: And in some ways you were maybe one of the biggest fans?

Allison Duerk: You could say that. I was getting on my way at least. I have definitely met bigger Debs heads than myself at this point, but we do call ourselves Debs heads too, for sure. You get it. But, at least I insist that we do.

Alex Chambers: The Debs heads see a guywith a vision that involved the workers themselves owning the resources that powered the economy. But Debs himself didn't start out thinking that way.

Allison Duerk: Everything we're looking at right now used to be the Chancey Rose farming orchard. So, like, Chancey Rose was, like, an early financier. I think he was a railroad owner in Terre Haute too. He was, like, actually a boss that Debs looked up to as, like, living in their own communities and, like, having to see the consequences of the wages that they pay and, like, putting more back into the community. But as owners, like, are no longer in your neighborhood or the next neighborhood over, whatever, Debs became less and less confident that employers could be trusted to do the responsible thing for the people who will make them rich.

Alex Chambers: That's because more and more, the owners themselves didn't live where their companies operated.

Allison Duerk: Controlling interests in utility companies were sold to national corporations in, like, Boston and Chicago, for example. Even as Gene was a national labor union figure, the union existed to pay for funerals. It was not going after employers for massive concessions. It wasn't trying to change systems or reconfigure how an economy could work, or whatever. It wasn't, like, militant necessarily and, for a long time, it was anti-strike, and Debs was too. He really thought that, like, with responsible employers, strong unions and like...

Alex Chambers: Responsible employers like the ones that he saw here in Terre Haute?

Allison Duerk: Yeah, exactly. Yeah, that he thought he saw. And like, laws from a responsive democracy. Like, we could curb the excess of capital and that capitalism would not be equal by definition-- it's in the word-- but it should be livable if we -- I don't want to just say put constraints around it-- but basically, put some curbs around it.

Allison Duerk: As far as, like, what has kind of wakened Debs up to all this too, like, he's seeing, for example, like, maybe some limited success with strikes, but Debs just pretty anti-strike for, like, the first, almost like half of his life really. At first he was really conservative. Again, like, only up to the white men. But also not demanding much from employers either. We are just fighting for a fair day's wage for a fair day's work. Which is, like, the classic labor motto from this era, which in some ways does persist todaytoo. So, like, if the switch men go on strike for a fair wage, you could pretty much bet the anti-strike farming and engineers are going to cross the picket line, and all an employer has to do is get scabs or strike breakers for one kind of worker and that's pretty easy. Like, you probably are not going to win that way. But seeing this happen over and over and over in different forms, convinces Debs that if we don't want to starve in the next century, we're going to have to find a way to counter this growing corporate power. If the railroads can combine and amass their influence, then why can't the unions do the exact same thing?

Alex Chambers: So, you were kind of learning or starting to learn all this in these classes?

Allison Duerk: Yes, more or less. So, as a student and as a band member, like I was in the marching band and the basketball band here and all four years that I was at ISU, we never got a scholarship or a stipend,which is how it often is, but not always how it is. And this is a working class campus, right? I knew from, like, experience with friends at other schools that there is money out there for, like, real compensation for the work that we're doing and, like I said, as a working class campus, like, we knew our fellow students would have to quit an ensemble halfway through the semester to maybe work to support themselves to get through. Which is not at all uncommon, but it also, in a case like marching band where you have drill, like everybody has a spot, like that can...

Alex Chambers: I didn't think about that.

Allison Duerk: Yeah, it affects everybody in some way. So, we were able to start organizing, basically, and we formed a band members association and we did research on other schools and we were able to kind of educate and agitate and, like, you might sort of say organize with our fellow students to say, you know what, it doesn't have to be like this. You know we're working really like a significant part time job doing this, and maybe giving up the chance to go earn wages somewhere else, or our study time, or our social time or whatever else, and connecting to people over, like, their individual struggles. Like, that's how this is done and it's working. Like, we're on the field, we're taking our water breaks, we're walking back to our buildings after rehearsals, or whatever, and then we started having meetings. And like, we had agendas and we took minutes, and we kind of kept it under the radar for a while, because we didn't want to get, like, found out and get in trouble or something for being agitators. But, in the end, like, the staff in the school of music, I should say the faculty in the school of music, were really really supportive and within a couple of years, and after kind of getting this up to the administrative level, they have a generous scholarship, and I think it's expanding right now to, I want to say non-majors too. Like, we did it!

Allison Duerk: It was honestly exciting. It brought me closer with my friends to be part of this collective effort, which is really what it's all about, and that's what our bands are about too, is the collective effort. Like, one person playing music, sure, that's fun, but it feels like practice really. But what's actually, to me, the most rewarding is the collective effort of dozens of people, maybe hundreds of people on a field, or in a rehearsal room, or on a stage like, getting to share with an audience the fruits of our labor basically.

Alex Chambers: Allison played the mellophone in marching band. If she and her fellow mellophonists, if they had decided their conditions were unworkable, and they were going to sit out football games until they had access to better spit valves, it seems like it would be pretty easy for the marching bands corporate board to just bring in extra euphonium players. Not the same I know, but close enough if you're trying to keep a tight horn budget. With those euphonium scabs crossing the line, the mellophone strike would fail. Eugene Debs foresaw that problem, maybe not in relation to mellophoners per se. So he realizes that (A) we probably have to be able to strike and (B) we're only going to be able to effectively strike if we are organized across the whole industry, rather than having like the firemen, be able to go run the switches. And so, he starts to think about that and then makes something happen.

Allison Duerk: Basically, like the idea of all different workers on a railroad line striking together would have been pretty, I don't want to say entirely unthinkable, but a pretty big advancement in how strikes could be organized. And so, like, the Great Northern Railroad, Minneapolis, St Paul to Seattle was going to cut wages for the lowest paid, so-called unskilled maintenance workers. The rest of this union was now strongest in the American west. They recognized if they can do it to maintenance, the bosses can do it to the rest of us and we don't have to stand for it. So, when talks fell through, Jim Hill wouldn't come to the table, the railroad's president refused to bargain, they shut the entire thing down, and it only worked because the engineers and the engine cleaners can strike together in one union. They actually refused to scab on each other and it worked.

Allison Duerk: You've got to get vast majorities in support of your goals if you're going to get real change.

Allison Duerk: I had my share of friends who struggled with sexual violence in college. You're seeing just abysmal response to that. Like, it really personally affected me and a few of us got together to form a feminist organization on campus and that was cool, but we don't want to be siphoned off either and, like, just work with students who might consider themselves feminists. Like, how do we broaden out.

Allison Duerk: A few students can go to administration or this or that body and get left out or told they'll send it to a committee and then it's, by the next semester, like, forgotten about or whatever. But when you've got whole majorities on board for demand, that's undeniable.

Alex Chambers: Also undeniable is the fact that it's time for a break. When we come back, we'll stand at the crossroads of America and the downtown Jimmy John's in Terre Haute, which is where Eugene Debs first read Les Mis. It wasn't a Jimmy John's at the time.

Allison Duerk: I thought we might head downtown.

Alex Chambers: Sure.

Allison Duerk: And just across the road here. We are going to come up here on the crossroads of America.

Alex Chambers: Gee, that's cool.

Allison Duerk: So, that's why I wanted to head this way.

Alex Chambers: Great.

Allison Duerk: I think they're setting up for Blues Fest but I'm not totally sure. We're looking at Seventh and Wabash. So, Seventh Street is US 41. That's actually DuSable Lakeshore Drive, like up in Chicago. Like, technically, the actual highway is now Third Street, but this is the old route of US 41. And then Wabash Avenue is US 40, basically. But that will connect us to India's Washington Street and Indianapolis and will connect us to the state capital and after St Louis. But yeah, that's the old Seventh and Wabash.

Alex Chambers: Trains are also pretty significant here, right?

Allison Duerk: Oh yes. Eugene Debs' first jobs were working for the Terre Haute and Indianapolis railroad as a painter and as a locomotive fireman. That's where he starts to see first hand, it's just brutal conditions that left widows with no choice but to remarry as quick as they could, to not let the kids starve. And it's, of course, like you could call the life blood of a nation, or whatever.

Alex Chambers: Life blood or not, the tracks run pretty close to a historically significant sandwich shop.

Allison Duerk: Did you want a sandwich? Maybe you'd like to go. I'm not, like, really hungry yet.

Alex Chambers: Yes, I'm not actually. Maybe I should get one later, but we could go, we should go over there, at least.

Allison Duerk: You can walk by it at least, yes.

Alex Chambers: We should definitely walk by it.

Allison Duerk: It's kind of like construction workers or operators, like, they'll point out to their kids, like, I paved that sidewalk, or I built that building or whatever, and I'm, like, I delivered a sandwich there, I delivered a sandwich there. They were bad tippers, they were great tippers or whatever. But here's our Jimmy John's freaky fast gourmet sandwiches. This is the old site of the Debs grocery store, where Gene Debs grew up. So, we're at the corner of Eleventh and Wabash, on the northeast corner on busy days during the lunch rush. I'll just pull the car up right here. Sometimes the manager would run the bags of food out for us, so we could just take off and that. Usually, we had to go back in though.

Alex Chambers: Was it fun?

Allison Duerk: It could be. Yes, when people tipped well. It was nice to, like, be on your feet and it was kind of gamified too. Like, will you get a tip this time, will you not? But, like, what was difficult was we made 7.25 or 6.25 plus our tips. Like, eventually this changed, but we didn't get like a mileage reimbursement. It was just kind of, like, you can claim it on your taxes if you want to keep track of it. But, other than that, you get to keep your tips and because we don't make you report the cash runs it's, like, that was considered the quid pro quo basically. So that was rough.

Allison Duerk: Debs really understood America as a land of plenty. Like climate change has its own huge pieces of puzzle to fit in here, but we are on top of coal and oil deposits. We have so much land to go around, like we should, Debs thought, be able to feed and house and educate and care for all of us. He thought we could have, like, a billion people in the United States and still be able to care for everybody with how many resources we have at our disposal, if they could be used and distributed equally, or on the basis of need and use, instead of on the basis of what's profitable.

Allison Duerk: Debs saw coal shortages that were manufactured, families going cold, going hungry in the winter, even while there's enough coal under our feet, for example, to keep us all warm, because it wasn't profitable to mine that coal. And, instead, workers were kept idle, as in unemployed, and he saw the system as only benefiting a few at the very very top to maintain and protect their profits at the expense of the wellbeing of the rest of us, and that is why Debs is campaigning on industry operative for need and use, instead of for profit.

Alex Chambers: And he got pretty popular with that.

Allison Duerk: In a sense. He was marginal, you know?

Alex Chambers: Relatively speaking.

Allison Duerk: Yes. It's all relative, right? Yes.

Allison Duerk: Well, I mean, like, the fact that Debs, I mean, at his peak did earn 6% of the popular vote in 1912. That is nothing to laugh at or sneeze at, I guess in, like, our first past the post voting system where it's really really hard for third parties to make inroads, compared to these two strong parties that dominate the system. The fact that Debs is able to get even numbers like that is remarkable in its own right.

Allison Duerk: It's not like you just run up to the front door. Like, you would have to go into their dorm and, hopefully, they would be waiting for you in their lobby. And if they're not, you can't go up in the elevator, that's against the rules. So, you would have to call them and wait for them to come down, and the longer you're waiting, the more you're missing out on the next delivery that could be a real tip too. Like, if I didn't get tipped, it was, like, I paid for the gas to bring them their food, basically, on a 7.25, on a minimum wage. Like, if you're listening outside of the state, like, send help. Like, we're still on 7.25 an hour here.

Allison Duerk: We're standing right where-- like the store's up front and they lived in the back. So, like, this was the home base for Gene Debs' parents, his four sisters and his younger brother. This is where he's reading Les Mis, over and over in French and reading Thomas Paine and Patrick Henry and all the rest too, and like, developing this huge, huge love for Abraham Lincoln, which who among us? But this is where it really all started.

Allison Duerk: At the time of his sentencing, Debs gave a speech that he thought might have been his last public address, at least, outside of a jail or prison. Debs was facing a ten year sentence and knew he would not survive ten or twenty years behind bars, so he said, "Your Honor, years ago I recognized my kinship with all living beingsand made up my mind that I was not one bit better than the meanest or lowest on earth. I said then and I say now, that while there's a lower class, I am in it, while there's a criminal element, I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free."

Alex Chambers: So it's 11.30. I want to give you a little bit of time to transition.

Allison Duerk: Thank you. Yes, I appreciate that. I'm going to get my pop out of the car.

Alex Chambers: I feel like maybe the last thing I want to ask, the last kind of idea, is about what it's meant to you over the years now to be working here. Like, it was exciting when you started. Kind of how have things changed for you? How's your thinking changed? What have you learned?

Allison Duerk: The significance of, like-- what's the word I want-- like a long-term commitment to something, it's not. I don't feel like it's very normal to, like, stay in your first, like, grown up job for as long as I have. Like, they tell you, like, on the websites, whatever, that you're supposed to transition after a few years so you don't get pigeon holed or whatever and, I mean, sure. But also, like, being able to have been here for so many years, I get to see the same people coming back and bringing their friends, bringing their family, kids who look a lot different when they come back the next time with their parents, and then they get to like appreciate and enjoy a little bit more, and connect with more than they would have when they were younger visiting.

Alex Chambers: Being able to, like, build relationships, friendships with people in the community and organizations around Terre Haute too has been super super valuable. It gets richer and, like, deeper, I guess, with age too. I'm not trying to say, like, I'm richer or whatever. Like, I mean, I feel emotionally richer because of it or whatever. But it becomes more meaningful to me, having had more time to, like, say and absorb it, honestly, and I think that can come through as being, like, more meaningful for our visitors and volunteers, and everyone who works with us too.

Alex Chambers: Do you still eat at Jimmy John's?

Allison Duerk: Rarely. Sometimes I get a craving and I might get a drive-thru at the other shop. But also, like, I have ordered delivery over to the house from here, but I try to tip very, very generously and that's how I can like live with it.

Allison Duerk: I really hope that, like, Terre Haute and the people here can see Debs as like a symbol of optimism too, and I'm not trying to water down his radicalism but, like, he really did believe that a better world is possible, like always, no matter how bad it gets. That the midnight is passing and joy comes with the morning, and all it takes is all of us coming together to fight for what we know is right.

Alex Chambers: And that's our show. If you know someone or are someone who's dedicated their life to a relatively obscure but important figure or cause, we'd love to hear about it. Send us an email or a voice-mail through the contact tab on our website, wfiu.org/innerstates. And if you liked the show, give us a rating and review on your favorite podcast app. It will help other people find it. And tell us what you've been up to while you listen. Like, maybe you decided to take a road trip and you downloaded a bunch of your favorite podcasts. Ah!. And you also grabbed the latest Inner States. Oh, thanks!

Alex Chambers: And about an hour after you crossed over into Indiana on US 40, among the vast flat expanse of cornfields east of Indianapolis, your mind started racing, trying to figure out what you're going to owe on your taxes next year. Another one of your accounting spirals. And you've realized you needed to calm down and, normally, when you start running the 1040 in your head, you just go over to a dispensary and then a hotel. You're not going to keep driving, you're responsible. But there are no dispensaries in Indiana, so you found a rest stop and pulled in and just started praying to whatever higher being might be out there, muttering over and over.

Allison Duerk: If you're listening outside of the state, send help.

Alex Chambers: And nothing happened until you thought, wherever you go, there you are, and so you turned on a podcast from inside the state and Allison Duerk's passion for Eugene Debs calmed you right down. Like that, give us a rating. End of story.

Alex Chambers: Okay, we've got your quick moment of town sound coming up. But first, the credits. Inner States is from WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana. It's produced and edited by me, Alex Chambers. Our Associate Producer is Dom Hiab. Our Social Media Master is Jillian Blackburn. We get support from Eoban Binder, Alexis Carvahall, Natalie Ingles, Luann Johnson, Sam Schemenauer, Payton Whaley, and Kayte Young. Our Executive Producer is Eric Balstridge. Our theme song is by Amy Oelsner and Justin Vollmar. We have additional music from Ramón Monrás-Sender and the artists at Universal Production Music. Alright, time for some town sound.

Alex Chambers: That was waiting for a sandwich at Jimmy John's, Terre Haute, Indiana. Until next week I am Alex Chambers. Thanks, as always, for listening.