Phoebe Wolfskill: This was going on historically in 1935. Let's take that as a starting point and say, okay, where are we now? Are we trying to forget? Which I think a lot of politicians wants us to forget or not talk about at all. Or are we raising these questions and how do we deal with the victims of lynching now? How do we try to commemorate who they were, but also, make people aware, look, this is what was going on.

Alex Chambers: Reminding yourself and your community that lynchings happened in your town, it's a way to take responsibility for the past and to think about how the past is still with us. This week on Inner States, two stories about people using art to remember the past and, ideally, change something in the present. That's coming up right after this.

Alex Chambers: The arguments over what its opponents call Critical Race Theory in classrooms or over banning books about race, over statues of Confederate generals, these are all arguments about historical memory. What parts of our history are we willing to remember and what happens when we choose to forget other aspects? The work of remembering is ongoing and, I don't know, for those of us who don't live in former confederate states, it can be easy to think, it's just down there that people should be thinking about the Civil War or Jim Crow. Here in Indiana, there were plenty of lynchings. What do we do with that memory? How do we remind ourselves that the past is still with us? That the questions of the past are still unanswered. I have two stories today about memory work, about how art can keep these conversations going. Coming up later in the show, two competing anti-lynching exhibits from the 1930s, and remembering lynchings here in Indiana. But first, a story about a photographer who uses his breath to think about nuclear war. Here's producer Avraham Forrest.

Avraham Forrest: Kei Ito descended from a bomb.

Kei Ito: My grandfather was in Hiroshima when the bomb exploded and most of his family died either at ground zero or radiation poisoning afterwards.

Avraham Forrest: His grandfather was a witness to one of the most destructive moments in human history, Hiroshima.

Kei Ito: He fled to Tokyo. Later, he became a quite profound anti-nuclear activist. He gave talk in States, UN. He was invited to go all over the place, but he too passed away when I was nine years old.

Avraham Forrest: Ito was born in Japan, but now he lives in Maryland and teaches in New York City at the International Center of Photography. His work is currently on display at the Eskenazi Museum of Art. His work grapples with intergenerational trauma and ongoing threats of nuclear war, but where did it start?

Kei Ito: I'm a 90s kid [LAUGHS].

Avraham Forrest: Growing up, Ito was surrounded by superheroes.

Kei Ito: I mean, like Marvel or even in Japan, Astro Boy.

Avraham Forrest: And he wondered if he was one, too.

Kei Ito: So many superhero in my generation gain superpower out of exposure to the radiation. It's kind of interesting because I saw the reality of what radiation did to my grandfather or many people who associated with my grandfather. Meanwhile, watching the cartoon or comic book that was giving the superpower that can fly around, breathe fire or glow in dark.

Avraham Forrest: So, he looked inward.

Kei Ito: Then I always start thinking about then, am I a mutant? What superpower did I get? [LAUGHS] Can I breathe really hard, see if I can breathe fire. No, I couldn't. Can I fly? No, I couldn't. I concluded with, maybe making art is my superpower.

Avraham Forrest: Ito moved from photography to cameraless photography. He describes his approach as abstract. Dealing with Hiroshima, he says, is not so straightforward.

Kei Ito: My great uncle, my grandfather's brother, one of the only remaining family that's still alive, that experienced Hiroshima and was still living Hiroshima and he never, never talked about his Hiroshima experience. When the Hiroshima day happens, he lived 20 minutes away from Hiroshima City where the memorial happens, but he never attended because it brings too much pain for him to even remember it. So, he never really talked about his experience, unlike my grandfather, but he did tell me his firsthand experience of what it was like and in the end, he said, none of the words that he can say can convey or explain what he witnessed that day. I think that's one of the reasons why my artwork became so abstracted is because its impossibility of trying to visualize this experience.

Avraham Forrest: Sungazing Scroll: 2022 is currently on display at the Eskenazi Museum of Art. I asked him to show me.

Kei Ito: Sungazing Scroll. I make this scroll every year, once a year. So every year the look is completely different. It spans usually from 80ft to as long as 180ft.

Avraham Forrest: This long scroll descending from the ceiling was made with light, photosensitive material and Ito's own breath.

Kei Ito: I essentially created a Camera Obscura. Essentially, I darken my studio space only letting a little bit of direct sunlight from the window and in front of this small aperture, I pull the paper in front of this aperture to have the paper exposed to the sunlight and what I did was I pulled a paper whenever I held my breath. So when you see the scroll, there's a thin black line in the middle.

Avraham Forrest: It's a trail of pupil-like spots linked together by a single tail.

Kei Ito: Of the black circle, there I posed so it was getting more exposure as I was exhaling my breath.

Avraham Forrest: Red, orange and yellow fill the paper and the circles are pure black.

Kei Ito: And then representation of my breath.

Avraham Forrest: Cameraless photography is essentially disassembling photography. It's about exposing light to photosensitive materials leaving shadows and images which make up the art. But it's more than materials. It's about intention. For example, Ito breathed 108 times into Sungazing Scroll: 2022.

Kei Ito: Which connect to Japanese Buddhism as well as Japanese culture itself that in New Years Eve to New Years Day, so many of the temple in Japan strike this human sized bell 108 times and by hearing each bell toll, you get rid of one evil desire and after hearing 108, you face the new year essentially cleansed. But I used this number as my childhood memory, but also the idea of redemption.

Avraham Forrest: He describes it as a performance. We talked about it back in the studio.

Kei Ito: So, I even consider the artwork itself is a performance that actually happens in either the dark room or my studio and even though people don't see the performance itself, they see the artifact, they see the result of my act in the studio or darkroom, in the galley space.

Avraham Forrest: Ito's work is also big. His installations take up entire rooms, floor to ceiling. Whether it's prints of human figures or an entire wall covered in eyes.

Kei Ito: I started making room size artwork. Now I'm making work that takes upon entire war memorial or entire majority of a section of the museum or even the public space. I think what I'm trying to achieve with my narrative is so monumental and it is funny, I start calling my artwork a temporal monument or temporal memorial depending on which work it is. It only exists for the duration of the exhibit, but I think it acts as a memorial, which is a reminder of the past for the people and it's also a location that people can connect the past to the present themselves and think about the future.

Avraham Forrest: A lot of his work explores the impact of Hiroshima, but Ito stresses it's not just about the past, the nuclear threat is still very real today and that's something Ito was trying to show.

Kei Ito: There's a thing called Doomsday Clock that DC published every year.

Avraham Forrest: It's something that was developed by the bulletin of atomic scientists. The clock counts down to midnight and as of January 2023, we are 90 seconds to midnight.

Kei Ito: It's not just a nuclear weapon, but nuclear weapon has a lot of influence of this time

Avraham Forrest: What's midnight, you ask?

Kei Ito: Midnight being the nuclear annihilation of humankind. I believe we are 90 seconds away from midnight and that is the closest we've ever been for a really long time, but we don't talk about it.

Avraham Forrest: Essentially, the clock shows us how close humanity is to annihilating itself with its own technology. It's not just nuclear weapons either. The Bulletin considers other threats, especially climate change and biotechnology when setting the time. In 2023, it moved closer to midnight from 100 seconds to 90. The move, according to the Bulletin's website was, quote, "Largely, though not exclusively, because of the dangers of the war in Ukraine."

Kei Ito: Now between Ukraine and Russia, this nuclear war is very much possible.

Avraham Forrest: Ito's work starts in Hiroshima, but it doesn't end there. His art is also about the nuclear threat today and it's something he's working to bring more attention to.

Kei Ito: People forget history repeats and it's the job of myself, artist, to remind people, hey, this happened before, let's not repeat it again and not try to create another nuclear weapon and victims, or any kind.

Avraham Forrest: Ito's work will be on display at the Eskenazi Museum of Art until July 9th as a part of the Direct Contact: Cameraless Photography Now show.

Alex Chambers: WFIU's Avraham Forrest. We're going to take a break. When we come back, we'll talk about not one, but two anti-lynching exhibits that went up in New York City in 1935 and why there might have been some animosity between them. Stick around.

Alex Chambers: Inner States, Alex Chambers. Jim Crow in the US wasn't just a matter of segregated schools and drinking fountains, it was also a period of anti-black racial terrorism. Some would say that period hasn't ended, although I would say it has certainly transformed. One of the major forms of terror during Jim Crow was lynchings, and lynchings happened throughout the US, not just in the south. In 1935, two organizations decided to create exhibits of anti-lynching art and, as I mentioned, they were in a bit of competition with each other. There's a new exhibit now on the Indiana University campus that recreates aspects of both of those and it also raises questions about the memory of lynchings in Indiana. I talked with two of the curators of this exhibit. Phoebe Wolfskill is in the Departments of American Studies and African American and African Diaspora Studies at IU and Alex Lichtenstein is in American Studies and History. I asked them to start with some historical background on lynching itself and how art has been used to struggle against it.

Alex Lichtenstein: So, as most of your listeners probably know, lynching is essentially group vigilante violence directed, more often than not, at African Americans, leading to death, usually by hanging, but not always. Really, in terms of the way we are focusing on it in our exhibit on anti-lynching art is looking at the role of lynching as a form of racial terrorism as Bryan Stevenson of the EJI, Equal Justice Initiative, calls it and racial terrorism, in particular, for enforcing white supremacy between the end of reconstruction, which would be the 1870s through about, really, the beginning of the modern civil rights movement in the 1950s. Many people might regard the murder of Emmett Till as one of the last classic lynchings. Now, often one of the more horrific aspects of lynching, designed indeed to terrorize African Americans and black communities, particularly, but not exclusively, as we'll talk about, in the American south was that it was often a public spectacle. So, it was designed to create a sort of narrative force that would tell white people that they had the right and could do this with impunity and tell black people that they better not step out of line, less they become a victim of this kind of violence.

Alex Lichtenstein: So, most notoriously, the peak of lynchings in this country was in the 1890s, I forget the exact dates and figures, but roughly 1880 to 1950 there were 4,000 people lynched and the vast majority of those people were black and the vast majority of those lynchings were in the American south and most notoriously, and then I'll pass it over to Phoebe, the accusation that was often made, often quite untrue, was that this was a way of defending white women in the south against African American men who were deemed to be sexually vicious and indeed accused often of rape even when that was not what was going on at all. So, the artworks that we're looking at, that Phoebe will speak about, try to engage with this history at the time and subsequently.

Alex Chambers: Great, and actually before we get to the art if we could just stick for another minute with the concept of racial terror that Bryan Stevenson has helped us think about. I think it's pretty clear in what you said already, but if you could just make it crystal clear how lynching was not just a series of incidents of individual racism, but a system to create a power differential.

Alex Lichtenstein: Yeah. Lynching should not be understood as some sort of anomalist fringe instance of racial violence, but absolutely intimately connected with the system of white supremacy in the American south from the 1880s through the 1960s, namely the enforcement of segregation, the denial of voting rights, the enforced poverty that African Americans had and basically black second class status as citizens in the country. Lynching was the violent arm of that entire systematic dispossession and oppression that black people, especially in the American south, suffered. So, not something apart from that, but absolutely central to it was the sanction used by whites and by the white community to enforce white supremacy when blacks stepped out of line as whites understood it.

Alex Chambers: All right. Great. Thanks.

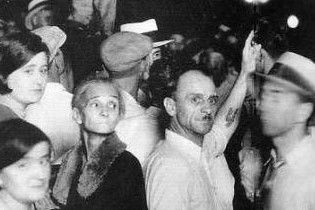

Phoebe Wolfskill: So, the use of visuals, I'll just start a little earlier, Ida B Wells was the great anti-lynching crusader and probably one of the first to use visuals and that being the photographs that often accompanied a lynching and that was part of the legacy of that white supremacy as well, the idea that you can photograph this, that the people in those photographs are not shielding their faces because they know they won't be persecuted for this crime. That was part of reinforcing this act as well, allowing these photographs to be reproduced as postcards and allowing them to travel around the nation as then another reinforcement. Ida B Wells used it in the opposite way in her publication, the Red Record, which did all of the research that Alex described. What were these incidences? Why was a person lynched? Did he fail to step out of the way of a white person or something like that? So, she collected that data, but she also used photographs and then changed how they mean. So, instead of suggesting this continuation of white supremacy, is changing them into an image of white savagery, of white violence.

Phoebe Wolfskill: So, she was doing that work, the NAACP was doing that work and reproducing lynching photographs in their publication, The Crisis. So, this had been a conversation in a lot of the Harlem Renaissance literature in particular of the 1920s, people deal with the theme of lynching. Some of the visual artists do as well. But the exhibition that we have opened is focusing on two anti-lynching exhibitions from 1935, one that's sponsored by the NAACP and the other by the John Reed Club, the Communist Party USA that uses art to speak back against this crime, to show the bloodiness of it, the inhumanity of it, the lack of a basic moral code, but also that it's part of a larger system of white supremacy. It's institutionalized. So, the NAACP show was trying to create awareness, but also to make people support a particular bill that would curb lynching or at least put up some obstacles to it taking place.

Phoebe Wolfskill: The Communist Party USA had a different bill that they supported, that they knew would never pass, but would be more stringent in terms of prosecuting the mob, seeking out who did this act, that kind of thing. In both cases, they have work that a variety of artists, black, white, Asian, Mexican, et cetera, that had already been working in that theme, had already looked to the American scene and said, this is part of who we are and we have to say something about it, but also, with these two exhibitions, some of them created work specifically to speak back to this violence. Some of the images are brutal, but their point is to say, look at what is going on and a lot of the language is towards the south, but of course, lynching is occurring in all of the states.

Alex Chambers: Right. Okay, so the exhibit is unmasked, the anti-lynching exhibits of 1935 and community remembrance in Indiana and in some of the introductory materials that I've been able to see, you talked about how these two exhibits are approaching the concept of using art and visuals in slightly different ways. Can you talk a little bit about the distinctions between the two exhibits and how they were trying to bring attention to this?

Alex Lichtenstein: So, again, why don't I start on the two exhibits by giving a historical context? Then I think Phoebe can talk about the different aesthetics in each show. So, the historical context here is very important and that's that the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the most venerable black rights institution in the country at that time and it existed for about 25 years at that point and the Communist Party, which was indeed explicitly interracial and argued on behalf of black and white workers working together to overthrow capitalism, they were locked in the early 1930s into a bitter rivalry over the best way to represent anti-racism and that rivalry stemmed, in particular, from something known as the Scottsboro Boys case.

Alex Lichtenstein: The Scottsboro Boys case was an infamous legal case that began in 1931, ironically enough on the day that Ida B Wells died as a matter of fact, in 1931. This was a case where nine young black men were grabbed off a train in northeastern Alabama. Two white women were riding on the same train, that is they were riding the rails. It was not a passenger train, it was a freight train and the white women, worried about being arrested for prostitution or vagrancy, pointed a finger at the young black men and said, they raped us. The white community in northeastern Alabama patted itself on the back because they did not lynch these nine young men. They brought them to trial and I think after two days they convicted them and sentenced them to the electric chair. So, that was southern justice at the time. That was seen as, oh, we did it right this time, we didn't just lynch these guys.

Alex Lichtenstein: So this became a giant cause célèbre and the NAACP and the Communist Party locked horns over who would defend the Scottsboro Boys and their case. It went on appeal over and over again and in particular, they divided sharply over the best way to do so, with the NAACP urging a quiet, calm, legal strategy. "We'll take this to the courts, we'll appeal, we'll get them off through legal means." The Communist Party was insisting that this should be publicized as a massive miscarriage of justice, which it certainly was, but that rather than just fight it through the courts, that it should be fought agitationally by organizing people really all over the world, which is what happened, to protest against the Scottsboro trials and to defend the Scottsboro Boys as they were called in the lingo of the time.

Alex Lichtenstein: There were protests in New York, there were protests in Moscow, there were protests in Germany, there were protests in South Africa, all around the world, although I don't think there were actually any protests in the American south where it would have been extremely dangerous to do so. So, it's in that context that these two shows in 1935, agitating around the issue of lynching, closely related to the Scottsboro case, took on this bitter rivalry. So, the artists got swept up into that in a way. I think that Phoebe can speak to that better than I can.

Phoebe Wolfskill: Interesting about it is that some of the works that were in the NAACP show were also in the John Reed Club show. They sort of moved over. I will say, the John Reed Club show didn't have a lot of time to put it all together, but they had already been publishing a lot of that work in the New Masses.

Alex Chambers: I'm just gonna jump in and add about New Masses. It was a Marxist magazine in the 30s, closely associated with the Communist Party USA and it was a pretty big deal. It published people like Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Dorothy Day, Ernest Hemingway. You could say it was the magazine of the American cultural left during the depression.

Phoebe Wolfskill: Yes. So, the NAACP show, if you want to speak generally about the differences in artistic approach, this is one of the critiques from the Communist Party, there is more attention to the individual black victim as a Christ-like sufferer, often formed like a crucifix. John Steuart Curry's work where this black man is hiding in a tree and the mob is coming after him and he looks like a blameless victim, like Christ. So, the criticism from the John Reed Club was to say, "Well, you're just focusing on this kind of Christian theme and this individual instead of looking at the larger picture." But there's also a Paul Cadmus that deals with the sort of maelstrom of violence, that it's sort of pulling you in. There's a Reginald Marsh work, which allows us to focus on the crowd. It's called, This Is Her First Lynching and it's a little girl that's being put on someone's shoulders to look and as viewers, we are not able to see the violence, but rather the crowd, which is an important strategy as well.

Phoebe Wolfskill: In the John Reed Club show, there is more, I would say, symbolism and more of a take on larger institutions. One of the works that we have in there is by Hyman Warsager where the lynched victim is springing from this enormous trunk that is coming out of the US court building. So, it's sort of an arm of the institution, the court system. The court building has a swastika on it, too. So, it's referencing fascism abroad as well. So, there's more of that kind of imagery in the John Reed Club show, and people fighting back, I think, as well. So, regardless, the artist in either show wanted to see an end to lynching, but they often had different ideas about how you get there, visually.

Alex Lichtenstein: Thinking about the politics of it, to put it in the briefest terms, the NAACP tended to regard lynching as something that was often carried out by poor whites in the south and the Communist Party strenuously disagreed with that and advanced the analysis that the strings were being pulled by southern Capitalists, essentially, and even perhaps by the bourgeoisie in the north and that the only way to stop lynching was for poor whites and poor blacks to stand up together and fight against it. Some might say that was a little bit of a pipe dream, but that was their political analysis at the time and that's what differentiated them quite sharply from the NAACP. We have one amazing work by Hugo Gellert, which appeared in the New Masses. Actually, it depicts the Scottsboro case and it suggests that the NAACP is actually part of the lynch mob, essentially, coming for the Scottsboro boys and it's the International Labor Defense, the Communist Party legal arm that's trying to rescue them and the NAACP is essentially part of the mob.

Alex Lichtenstein: I see that and it just astounds me that Walter White, who was the director of the NAACP at the time, invited some of the left wing artists like Hugo Gellert to contribute to the NAACP's show. I'm not sure what he expected them to say, but sometimes I think maybe he expected them to just reject it and then he could say, "Well, I did invite them." And of course, the party said, "Oh, we weren't even invited. That's why we had to set up our own show." It was very bitter. It really was.

Alex Chambers: This is Inner States. I'm talking with professors Phoebe Wolfskill and Alex Lichtenstein about the exhibit of anti-lynching art they curated along with Doctor Rasul Mowatt. When we come back, how they want to use that exhibit to get us talking more about what's happened in our own backyards. Stick around.

Alex Chambers: Welcome back to Inner States. As Phoebe and Alex worked on Unmasked, bringing together the two anti-lynching exhibits from New York in 1935, they got to wondering, how have things changed? How are we commemorating those acts of racial terror?

Phoebe Wolfskill: Are we trying to forget? Which I think a lot of politicians want us to forget or not talk about at all. Or are we raising these questions and how do we deal with the victims of lynching now? How do we try to commemorate who they were, but also make people aware, look, this is what was going on. So, we've got a variety of community groups throughout Indiana who have put up plaques, who have collected soil related to the EJI project.

Alex Chambers: Okay, jumping in again. The EJI is the Equal Justice Initiative. Along with establishing the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, also known as the National Lynching Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, they've been memorializing lynchings across the country by collecting soil from lynching sites and displaying it in jars.

Phoebe Wolfskill: As a way of commemorating victims in their home town.

Alex Lichtenstein: And this is really something that evolved over time. When we began, Phoebe, myself and Rasul Mowatt, our third collaborator, talking about this, we really imagined it at first as an exhibit that was going to revisit or reconstitute those two 1935 shows, which I think was a good vision, but it was rather academic as it were. As we started talking to more people, engaging with communities and as various events happened, the murder of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, one can go on, Michael Brown, we realized that we really wanted to find a way to connect the 1935 shows to these present examples of what we call memory work. In particular, I would have to say, we were inspired by the opening of the Equal Justice Initiatives anti-lynching memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, which opened I believe in 2018, five years ago.

Alex Lichtenstein: That really opened up a whole new set of possibilities. So, as Phoebe says, all across the country, but in Indiana, there are four or five different memory groups trying to commemorate examples of racist violence that occurred in the state of Indiana. Most notoriously, and this brings us to the key element here, a 1930 lynching in Marion, Indiana, which is about an hour and a half northeast of Indianapolis. This was a lynching that became notorious because there is and was a photograph of this lynching that, I think it's fair to say, was and is the most widely circulated visual image of an actual lynching that occurred, the lynching of Abram Smith, Thomas Shipp and a third person, James Cameron, who escaped the mob that night.

Alex Lichtenstein: So, this image circulated widely and we've made that image part of the exhibit, not to shock people with it, lots of people have seen it, but to show how the image itself traveled in a way from being, as Phoebe had suggested at the very beginning of our talk, from being a form of pro-lynching propaganda that whites would share with one another to becoming a piece of anti-lynching agitational material, both in the way it was republished in newspapers at the time, in the Daily Worker, in the Chicago Defender and in the Crisis and then how it's been appropriated by artists in art works subsequently over the past 50 or 60 years. So, there's that focus on Marion and the Marion lynching, which is also well known because it generated the music by Billie Holiday, Strange Fruit.

Alex Lichtenstein: It is the centerpiece of the exhibit, but also, the efforts both of artists in the 30s and the 40s to focus on those left behind, as we say, the family members, the people who have to cultivate the memories of their loved ones who have been lost to racist violence and then this more contemporary effort for communities to find a way to reckon with this past and to force communities to recognize that this happened, usually on their courthouse square. That's often where these things happen.

Alex Chambers: So, I'd like to think a little bit more about this idea of memory work. Just a few weeks ago, I had Susan Neiman here who wrote Learning From The Germans, about how the Germans have tried to reckon with the history and memory of the holocaust in contrast, mostly, to how Americans in the US south have or have not done that. It's a challenge and I'd love to hear some more of your thoughts about how art and community practices can help us look back at this history in these situations and do something differently than what we've been doing because it's not as if we don't already have memory work happening around this, but it's usually about memory of and nostalgia for the Confederacy.

Alex Lichtenstein: Exactly. Well, I'll start with the community work and then Phoebe can talk about the art. So, about two weeks ago, we had a workshop at Indianapolis in conjunction with or connected to the exhibit, but it wasn't really about Unmasked, it was really an effort to bring together people from all around the country, but particularly from the south, who are doing this local effort to commemorate racist atrocities in their communities. Sometimes it's a lynching, sometimes it's a pogrom as there was in Elaine, Arkansas, in 1919 and we had people from about a dozen different communities, from Elaine, Arkansas, from Oxford, Mississippi, from Union County, South Carolina, from Milwaukee where James Cameron eventually settled, that is the survivor of the Marion lynching and started a museum called the American Black Holocaust Museum.

Alex Lichtenstein: So, again, I think a lot of these people are inspired by, but not entirely on the same page as, the Equal Justice Initiative and are just doing really exciting, interesting work, bringing together interracial groups of people in these small communities to think about how they might commemorate these events and make these events part of the common memory of their community and of the social and physical landscape in their community. My favorite one really is this movement that's going on in Elaine, Arkansas, which in 1919 was the site of the murder of about 200 to 300 black people who were trying to organize to get a better price for their cotton. It's an infamous event and actually, several, about a dozen blacks were arrested, of course, rather than the whites who did the deed and Ida B Wells visited them in prison in 1922 or '23 in Arkansas. So, another connection there. So, I've been very excited by these local grassroots efforts to do just this, to try and get a marker put up in Marion, in Terre Haute, in Elaine, Arkansas, in Oxford, Mississippi, and it's been thrilling to watch, actually. It's designed to displace that nostalgia for the confederacy, which still is everywhere. In terms of the arts, traditionally, I think, it focuses on sculpture and statuary, but that is beginning to change a bit, I think. So, Phoebe, what's your sense?

Phoebe Wolfskill: Yes, it's certainly worth admitting that a memorial and visuals can only do so much. They're not gonna solve the problem, but they create awareness and they create a conversation, which is so vital and W.E.B. Du Bois famously said about the south and black reconstruction, he said, basically, the south lost the civil war, but they seem to have won the history, the idea that all of these sculptures are still up, but the attack on those sculptures after the murder of George Floyd was so meaningful and I'm thinking of that huge Robert E Lee in Richmond, that it's having to take on those voices that this is no longer acceptable to us. So, the tearing down of monuments also seems very, very significant. But the more we poke around, the more we see how many people are doing this kind of work and how important it is.

Phoebe Wolfskill: I'm from Colombia, South Carolina. The statehouse notoriously had the confederate flag over the statehouse for a long time and then it was moved to the grounds next to the Confederate Soldier memorial, which made it even more visible and then finally, that was taken down. You've got these monuments to the Confederacy, to Ben Tillman, to Strom Thurmond, to these various figures and then a black organization has put up a sort of counter memorial that speaks to African American history and it's much more interesting aesthetically because it is something you walk through as opposed to just stare up at this equestrian statue, but it's also bizarre because it's as if these memorials are separate, as if this confederate history took place separately from this black history, which of course is not true. So, I think the weirdness of it is also sort of interesting, to put that there and say, wait, there's something we're missing here. And that seems to be going on in a lot of places.

Alex Lichtenstein: So, Ben Tillman is a particularly interesting figure, actually. So, Ben Tillman was a long time senator from South Carolina, not attached to the confederacy, a senator who oversaw post Civil war reinstitution of white supremacy. And Tillman, not to put too fine a point on it, was basically a psychopathic racist murderer. He lead mobs that killed people in Edgefield County, South Carolina, during the overthrow of reconstruction and the reinstitution of white supremacy in South Carolina and he took to the floor of the senate numerous times to vocally defend lynching. Not just to say, we don't need an anti-lynching bill, but to say, lynching is the right thing to do, it's the only way to protect white women from these black rapists. That was said that on the floor of the senate in the 1890s and after. So, I believe no one has torn down the statue of Ben Tillman.

Phoebe Wolfskill: He's still there.

Alex Lichtenstein: Still sits on the grounds of the South Carolina state capitol in Colombia and black people have to walk past this every day and that's an insult. So, the changing of that and the attempt to build new monuments is really important, I think.

Phoebe Wolfskill: I will say, to the Columbia historian's credit, if you go to the website on what's on the capitol grounds, they're very, very critical of what's there. So, they've done that at least. [LAUGHS]

Alex Lichtenstein: Okay, well, that's a start. Right.

Phoebe Wolfskill: And I know they're talking about pulling people down.

Alex Lichtenstein: Well, there's someone who should be pulled down in my view, Ben Tillman.

Alex Chambers: Yeah. He's not maybe as symbolically significant as Robert E Lee of course. I'm curious if you've seen any resistance. Obviously, with the statues and stuff, it's hugely controversial. Have you seen resistance with any of the more localized groups or things that you've been working on?

Phoebe Wolfskill: Well, we've had multiple workshops to discuss the exhibition because the material is so very difficult, and Alex and I are very used to seeing these images and they are gruesome. So, part of what we've done, which Alex figured out, is we've got to have interpreters for this exhibition that can really help lead people through it so people don't just stumble upon it. But there is so much very, very important attention to black lives, not deaths. So, there's a real fatigue with looking at dead black bodies, understandably. It's horrible, right? And that's what it's supposed to be. It's supposed to be very disturbing, but understandably, some people don't want to see what's in the show. So, we have the warnings up and we have these kinds of things, but our hope is that to be willing to engage this material is to be willing to talk about it and know that this is a part of our history and how does an artist find a way to speak to this kind of injustice. How do we do this now? How did we do this in 1935? It's an important conversation to have, but it's difficult subject matter, for sure.

Alex Chambers: Yeah, and I actually have a follow up to that with regard to how to the imagery is working. As you said, people, there's a sense of fatigue with the repetition, especially with social media, of police violence, in particular, against black people and there's a lot of debate about how useful that is, that repetition. Whether it helps us be reminded of the ongoingness of this or whether it somehow reiterates it. And so, I'm curious how does this exhibit intervene in that conversation as well?

Alex Lichtenstein: That's a great question. So, we may have different answers to it. So, one of the difficult things about imagining this exhibit from the get-go was precisely this issue. On the one hand, it's really important to show these images, they're historically significant and they were, indeed, a central part of the anti-lynching campaigns, dating all the way back, as Phoebe suggested, to the 1890s and Ida B Wells. Walter White was quite clear in 1935, yes, we want to shock America's conscience with these images so that we can pass an anti-lynching bill, which, by the way, did not pass because the southern Democrats blocked it and it finally passed in 2022 as the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act. At the same time, as you're asking, there is this sense of, okay, do we have to look at more lynching images? Do we have to look at more lynching postcards?

Alex Lichtenstein: There's this infamous exhibit 20 years ago called Without Sanctuary, that was just the lynching postcards, which were not designed as anti-lynching agitation, but which were designed as boasts essentially. Here, we did this and you can't touch us. So, we've been ambivalent about that from the get-go. I think Phoebe and I agree that in terms of historicizing this for 1935, these are the images that were shown and they were shown to provoke an anti-lynching response and we wanted to remain true to that up to a point, but as we started thinking about it, we thought, but we need to show some other things as well. We spent a lot of time focusing on images of the crowd, the perpetrators. We even work in a few works of a guy named Ken Gonzales-Day who has repurposed both the anti-lynching art and the lynching postcards by erasing the bodies. So, we have a discussion of that, a kind of visualization of that using some of his works.

Alex Lichtenstein: As Phoebe suggested, we also turn to artists who are representing those left behind, which doesn't focus on the murdered body, the physicality of it, but on the people who have to live with the loss. Then, thirdly, there's the emphasis on the memory work, which actually, once you go into the exhibit, you'll see that the final wall is four giant panels of photographs taken at commemorative events in Terre Haute, Mount Vernon, Marion and Indianapolis where this memory work has been going on. So, I think we regard those that we're trying to historicize the use of images of black death, but then mitigate it with other forms of imagery. Whether that works or not is up to the viewers, I guess.

Phoebe Wolfskill: Right. I mentioned Reginald Marsh before where he shows us the crowd and that's back in 1935 and then we look at works by Ken Gonzales-Day with the erased body, but also there's a video of a piece by Kerry James Marshall where he describes taking the Marion, Indiana, image and then focusing on three women in the crowd, so that we have to think about that crowd and who were these people and what kinds of things get passed down from generation to generation. So, we see similar strategies being used, again, in a different way and that's important, too. I do think it's difficult imagery. We can't control how people respond to it, but that's part of the reason why we have people that we've hired to help interpret it so that at least there's a conversation going there, but I think we've tried to be very careful about how we balance it, like Alex says, that we don't just end with these images, but where do we go now? How do we commemorate this? What do we do with this?

Alex Chambers: And that would be my last big question, where do we go now? What do you hope this takes us forward into?

Alex Lichtenstein: I'm hesitating because this is difficult. It goes to this question of opposition or resistance. My initial vision, our initial vision for this was that we would have this exhibit in Marion, Indiana, the sight of this lynching and I still think that could happen, but people in Marion were a little bit resistant to it. Not necessarily white people, although white people in Marion would prefer not to talk about this, but the descendants of the men who were lynched. And so, there's a very vibrant movement going on there, but they didn't really want us as outsiders coming in and stepping on that and that's understandable. I hope once they see the show that they'll realize this could help them with agitation, essentially, so that there will be eventually a memorial placed on the courthouse lawn and the Grant County Courthouse in Marion, Indiana because as we found out at our workshop two weeks ago, we were reminded there is nothing there. You can walk across that town square now which looks like the Bloomington town square and you would never know, unless you knew and everyone knows, that there was lynching there August 7th, 1930.

Alex Lichtenstein: So, that's my small hope is that there will be some kind of commemoration, some kind of marker, something that the community can decide what it should look like there. Then, I think our larger ambition and certainly what we've gotten funding for, under the guise of this larger ambition, is that somewhere in Indiana, probably in Indianapolis, there will be a larger memorial or marker to the history of racist violence in Indiana. But really, as Phoebe said, I think it's just about prompting conversations about how to remember this stuff.

Phoebe Wolfskill: Yeah. I was thinking big goals, where does it end, I was thinking egalitarian society, end of mass incarceration, stuff like that, but for now this is what we can do is to, okay, how do you provoke these difficult conversations.

Alex Chambers: Awesome. Well, this is great, thanks so much.

Phoebe Wolfskill: Thank you.

Alex Lichtenstein: All right, thanks, Alex.

Alex Chambers: That was professors Alex Lichtenstein and Phoebe Wolfskill. Along with professor Rasul Mowatt of North Carolina State, they curated Unmasked, the 1935 anti-lynching exhibits and community remembrance in Indiana. Unmasked is at the Gayle Karch Cook Center for Public Arts and Humanities on the Indiana University Bloomington campus through April 28th. You need to reserve a guided tour to go.

Alex Lichtenstein: Most of the slots are booked up, although if people contact me or Phoebe, we'll find a way.

Phoebe Wolfskill: We'll find a way.

Alex Chambers: After the IU campus, they're in discussions to bring it to the Crispus Attucks Museum in Indianapolis. It's attached to the Crispus Attucks High School.

Alex Lichtenstein: We're very excited about that because it's not in a museum per se, it's really in a community space.

Alex Chambers: They also plan to bring it to the South Bend Civil Rights Heritage Center in the Second Baptist Church in New Albany. They say if listeners have a community space, get in touch. They want to share it widely. I'll put links to their faculty info on the episode page.

Alex Chambers: That's it for the show. This is Inner States from WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana. If you have a story for us or you've got some sound we should hear, let us know at wfiu.org/innerstates. Speaking of found sound, we've got your quick moment of slow radio coming up, but first the credits. Inner States is produced and edited by me, Alex Chambers, with support from Violet Baron, Eoban Binder, Mark Chilla, Avi Forrest, Luann Johnson, Jack Lindner, Yané Sanchez Lopez, Sam Schemenauer, Payton Whaley and Kayte Young. Our Executive Producer is John Bailey. Our theme song is by Amy Oelsner and Justin Vollmar. We have additional music from the artists at Universal Production Music. Special thanks this week to Kei Ito, Avi Forrest, Phoebe Wolfskill and Alex Lichtenstein. All right. Time for some found sound.

Alex Chambers: That was, you could probably tell, a roller coaster. Okay. That's it for this week. I'm Alex Chambers, thanks for listening.