Kate Schneider: We've medicalized mortality, and... medicine prioritizes safety. But safety at what cost?

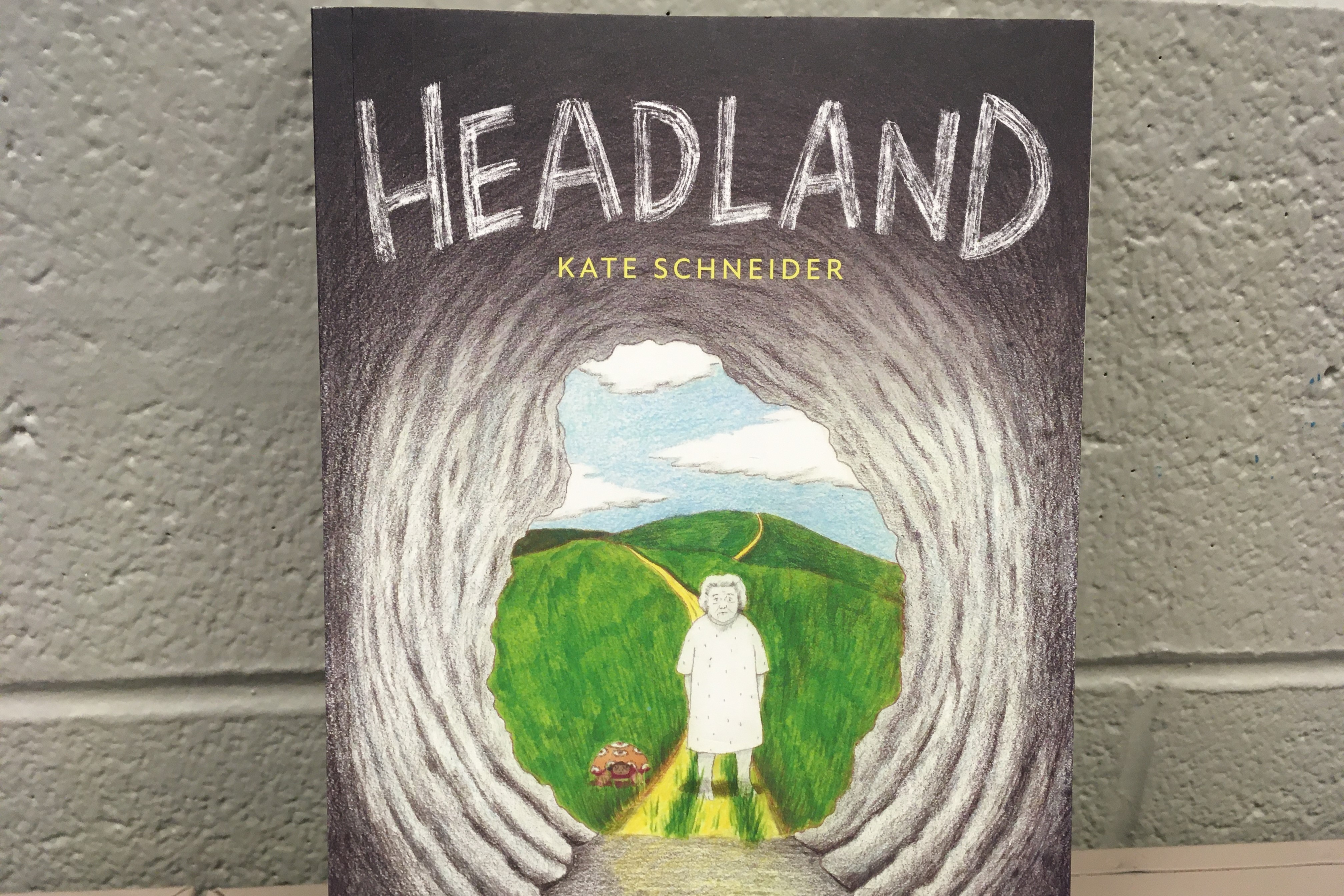

Alex Chambers: That's the question at the heart of Kate Schneider's graphic novel Headland. At the beginning of the book, Ruth, an older woman has a stroke. She gets taken to the hospital and spends the rest of the book there. Except for the worlds she explores in her imagination.

Alex Chambers: Headland is based on Kate's experience with her own grandmother, and a woman named Audrey who Kate cared for. Today on Inner States we talk about how our medical system approaches death and dying, and also about working on a graphic novel for six years. Plus IU Cinema director Alicia Kozma has a new way to fund independent films. That's all coming up right after this.

Alex Chambers: Welcome to Inner States, from WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana. I'm Alex Chambers. It's not news to say the medical system wasn't set up to take care of people's souls. Still, it's worth thinking about what happens to your soul when you have to go into the hospital; or into hospital, since the book we'll be discussing takes place in England. The book is called Headland. It's a graphic novel about an older woman named Ruth, who suffers a stroke in the first few pages. She spends the rest of the story in the hospital; or physically in a hospital at least, since we end up following her farther and farther into her own mental world, as she tracks into a colorful unknown with a tortoise at her side.

Alex Chambers: But there's something else you should know about the book too. It's not your typical graphic novel. Clean inked lines, speech bubbles, lots of action. It's all done in pencil. Some colored pencil but mostly graphite. And the drawings were made on rough paper. The pacing is different too. Not that much happens, and yet you totally get drawn into the world. There's such a tension to Ruth's perceptions. She spends a lot of time staring into the bare corners of her hospital room. And her expressions; tired, out of it, angry, but also finding some peace in the wilderness in her mind.

Alex Chambers: Kate Schneider is the author and she based Headland on two real people; her grandmother and a woman with dementia named Audrey, for whom Kate served as a caregiver soon after her own grandmother died. I invited Kate into talk about the book itself, which is gentle and beautiful. The challenge of caring for a person's inner life as much as their bodies, as they change in old age, and her life as an artist. So, Kate Schneider, welcome to Inner States.

Kate Schneider: Hi, thank you.

Alex Chambers: So, let's start with your inspiration for the book. Can you tell me about the two women who inspired the character Ruth?

Kate Schneider: Yeah. So my grandma was... how to describe her? She was... fierce, and Audrey was really fierce as well. My Grandma died right before I started working with Audrey.

Alex Chambers: Kate was living in Philadelphia at the time. Audrey also lived in Philly.

Kate Schneider: In a beautiful apartment.

Alex Chambers: And she needed care because she had dementia.

Kate Schneider: Yeah.

Alex Chambers: Before Kate's grandmother died she lived in Bath, in England.

Kate Schneider: The two of them were from the same place.

Alex Chambers: From the same part of England?

Kate Schneider: Yeah, no, Bath.

Alex Chambers: Both from Bath.

Kate Schneider: And the same neighborhood.

Alex Chambers: My god.

Kate Schneider: So I just feel like there was this-- and I really don't prod at the universe, but there was this thread. It's not like I thought, you know, they're so different. My grandma was so, like murdery, and then Audrey was like this diva. And so I think they were the two points on the Karpman's triangle, but I really loved working with both of them. I mean obviously I loved working with Audrey, and I loved being my grandmother's granddaughter.

Alex Chambers: That thread went beyond the timing. Kate's grandmother passing away just as Kate was meeting Audrey. It went beyond the neighborhood in Bath. Some of the connections were smaller.

Kate Schneider: They both drank the same sherry; the Bristol Cream sherry.

Alex Chambers: And some felt more significant.

Kate Schneider: My grandma had this tortoise, and then Audrey would love to watch the birds, and so I think there was this connection there with watching and caring so much about animals. They both had so much that was unarticulated, and there was just this way that I felt like my book was like a way to explore the puzzle of them as people.

Alex Chambers: At what point did you realize that you wanted to do a book about them?

Kate Schneider: I always kind of like zigzagged between art and writing. Sometimes I would think, Okay, art is my thing and writing, that's secondary. And then I thought, No, no, writing is my thing and art is secondary. And I think at some point I just thought, why don't I just do both? And, I talked my way into it, because nobody said no. [LAUGHS] In English. So I just did it. Yeah.

Alex Chambers: What do you mean, nobody in English?

Kate Schneider: Nobody in the English department said no to me doing a graphic novel. It was kind of silent. So there was a first iteration of the book, which was like me as a part of it. And I go to my grandma, and it's sort of like a dual coming of age story; and then I took myself out of it, because I think I needed to put myself in it to take myself out. And then I realized, okay. I wanted to live inside the story for a long time.

Alex Chambers: What was the coming of age that happened in the first draft?

Alex Chambers: So, it was kind of me coming to terms with my-- like looking outside myself and she was dying. It was like a connector. I could see her. I don't know, I thought it was strong but I didn't want to start there. I didn't want to start with myself and I realized I could be so much freer when I took myself out of it. When I changed her name to Ruth. She was my grandma for a long time.

Alex Chambers: It was autobiographical?

Kate Schneider: Yes. And then I realized this wasn't her story. This is my story of her story, and that freed me up a lot, and allowed me to combine and play and, the tortoise was like this element of humor that I could bring in. I think that comics are already in danger of being so heavy handed, because you're saying and you're showing. So I think that you've got to break it up, and I think that the tortoise provided that opening and allowed some dialog; she could talk to somebody.

Alex Chambers: Yeah, because she can't really talk otherwise.

Kate Schneider: No. I mean she's scaling mountains and she's going through caves, and she's talking. She's doing all these things that she can't do.

Alex Chambers: The pacing I guess is one thing that I found really lovely. It starts with this woman Ruth washing dishes in this old house, with old furniture and these old couches. And, it all looks really dated from the perspective of today, but not necessarily ratty or in bad shape, just different styles.

Kate Schneider: Well they were drawn from reference photos.

Alex Chambers: From your grandmother's house?

Kate Schneider: Yes.

Alex Chambers: Well it was very convincing. So did you know you were going to be doing this?

Kate Schneider: I did, yes. I worked on it for six years.

Alex Chambers: Over those six years the story kept changing. It wasn't until pretty late in the process that Kate realized she could combine her grandmother and Audrey into one character.

Kate Schneider: I think that's really what freed me up, because originally there was this storyline of grief, and the grief would be this thing that was a portal into the landscape of your imagination. And then I realized; well, Audrey is literally looking at the clouds and imagining her husband, who she'd lost in September. She was imagining him reclining in different positions, and I think because of the symmetry again, and the fact that they were like both-- they held hands in my mind. It was pretty beautiful, I think.

Alex Chambers: Were you working on the book already when you met Audrey?

Kate Schneider: Yes, I was. I kind of wanted to show it to her, but I didn't. I think I didn't. I mean, I know I didn't. [LAUGHS] I think I knew she'd see herself in it, and I knew she'd also, like all the particularities of her character; I smoothed over them a lot. But both women are in there for me.

Alex Chambers: Are there things in there that you didn't want her to see?

Kate Schneider: I think Audrey; I knew I didn't want my grandma to see it.

Alex Chambers: Why?

Kate Schneider: My grandma held me so tightly, and she said she held my mother so tightly, and I think that was the thing that made you feel like you wanted to wriggle away. And it was that tension; I knew that I needed this to be my story. And, for Audrey, I thought actually the opposite; that she'd make it hers. So I think with my grandma, she'd see everything that was disturbing about it, and Jesus, you know. And then Audrey would be too possessive, and so it was these interesting things that I clearly haven't explored too much, but [LAUGHS]. I think that for whatever reason I knew in my gut that I did not want either of them to see it. I got close with Audrey and then thought no way. And Audrey is still alive.

Alex Chambers: So you could still show it to her.

Kate Schneider: I know. [LAUGHS] Maybe I'll show it to her.

Alex Chambers: That's not resolved just yet.

Kate Schneider: No it's not. You'll have to get back to me on that.

Alex Chambers: It's interesting to think about how you were not necessarily immediately thinking about dementia, but you were thinking about grief, even before you have the grief, it seems like.

Kate Schneider: Yes. You know, I put my grandpa in there, and then took him out and put him in again, and then I took him out. I thought it was more powerful to leave him out, and to let home be this thing that people could interpret however they wanted to. I don't know if she says home at any point, but I think there's this feeling that Audrey and my grandma both refer to it as "I want to go home." Grief I think was this portal into nature. Nature doesn't ask anything of you, and I think that's really beautiful. It can give you what you need when you need it.

Alex Chambers: If you're just joining us, we're talking with Kate Schneider. Author of the graphic novel Headland, published earlier this year by Fantagraphic Books. When we come back Kate talks about the process of making the book, and how we should all keep drawing. This is Inner States, stick around.

Alex Chambers: Inner States, Alex Chambers. Kate Schneider started writing Headland as a memoir about her aging grandmother. By the time the book was done six years later, Kate had combined her grandmother and a woman with dementia who she had cared for, into one fictional character, Ruth. The book opens with Ruth washing dishes alone in her house. She sits down to watch TV and suddenly everything goes fuzzy. I asked Kate if she could give me a rundown of what happens in the book.

Kate Schneider: Sure so, [LAUGHS] there's not much to talk about.

Alex Chambers: We keep saying that, but there's a lot of different moments.

Kate Schneider: Sure. I think that it's in how I do it, but not what it is. So, my grandma, or Audrey, or Ruth, she has a stroke and we kind of move in and out of her world and her imagined world. We get deeper and deeper into that imagined world. I don't actually even know if I want to clarify that it's imagined. I think that that even is like, ooh. I think some people have referred to it as the "other world", or the "inner world", or "a third world". [LAUGHS] She gets kind of pulled back, again and again, and I think that that's really something that is hard for her because she doesn't really want to be pulled back. And I think that's the thing that we have a hard time hearing in America, and in the world, is that we've medicalized mortality, and medicine prioritizes safety. But safety at what cost?

Kate Schneider: I think that this tortoise was this reminder of life. Like this "Oh, the trees," and "I can't get up" and "help me", and "Can I come with you?" I think that at some point she's saying "Enough, I don't want this anymore." I think its brutal because we don't want it for her, because I think we're not really ready to accept the fact that she is done. That maybe she needs to take her next-- you know, she had the little bird that joins her and, that theres another room that she goes into, and we don't follow her in there. I don't think we're all ready to accept the fact that when the tortoise-- I want to say right now that I think the tortoise is okay. [LAUGHS]

Alex Chambers: I'm glad to hear that. And you're saying this because she gets frustrated with the tortoise, and ends up picking it up and shaking it, really angrily. It's very disturbing.

Kate Schneider: It is very disturbing, I think. I'd like to say that I believe that the tortoise is okay and has had some creatures come and care for it, and maybe a little leaf and some droplets of water. Maybe patched it up with some leaves. I think that's very nice of the creatures.

Alex Chambers: I'm glad to hear that, because when we last see it in the book it's shell is cracked. There's blood coming out of its shell, although it looks peaceful. But, I am glad to hear that it does end up okay.

Kate Schneider: I think we all make our priorities. I think if we have the freedom, we should all make our priorities with life. I want to eat however I want, and die at 79, and that's my choice. Like, you make deals, you know, and I think that this was her deal. This was her. Ruth was really ready to go and she really didn't want that catheter put in.

Alex Chambers: That was another really powerful scene, because when I was talking about her expression at the beginning in the intro; the intensity of her "know", and the shape of her lips was so powerful. You could really get a sense of how angry and how much didn't want it.

Kate Schneider: Yeah. I think it's like, who is it for? Is it for the hospital covering it's ass? Is it for the daughter who doesn't want to let go? I think it's all of the above.

Alex Chambers: Did you see moments like that either with Audrey or your grandmother?

Kate Schneider: Yes. I saw glimpses of it with my grandma, but I saw it with Audrey. She was fighting against actively dying, and was saying, you know, I want to go home, I want to go home. But, she didn't want to go home. She was pretty much kind of raging against the dying of the light, or whatever [LAUGHS]. I think that she says it, but I don't think she always knows what she's saying. But, I think on the other hand, our whole bodies are wired to not die. [LAUGHS] I think Audrey would be happy to die if she could just die peacefully, but I think that because there's this thing that's like "No, don't die" she doesn't want to die.

Kate Schneider: We don't get to die among our loved ones. We die in a hospital, and I think like I said before, medicine prioritizes safety, but safety at what cost? And I think that safety really doesn't account for dignity, it doesn't account for comfort. It doesn't account for any of those things; it's just "are you safe?" Then there's the question of what life? What are you fighting for? Are you fighting for a life that's empty, where you're literally just a heartbeat? No brain signal even maybe! I think there's a lot of work to be done, and I hope that this book-- I mean Jesus, [LAUGHS] I hope it kind of sheds some light on the internal. What could be going on for them? I think there's so much poetry and so much that could be explored, if we weren't fighting against everything. If we weren't fighting against the clock which is what, two more years maybe.

Kate Schneider: I think hospice is very generous. It's a very generous thing. Put them on palliative care, get them comfortable, and if they're able to, ask them questions. Tell their stories, because older adults and elderly folks have so much wisdom and they've literally seen it all, and we're not asking them questions.

Alex Chambers: That's interesting. And I think in the book too; you're right. We get a sense that people want to take care of Ruth physically. She doesn't want to eat, they keep wanting to feed her, but her daughter and the two different nurses, I don't think they ever ask how she's doing.

Kate Schneider: They're very concerned about her physical care, and I don't think they liked the answer. If they got the answer. But, I think you have to ask the question. By the way, I want to say that my mom wasn't even there; this is all imagined. I think we have to ask the question and we have to be ready to hear it. We have to bear the truth if we're going to ask for the truth.

Alex Chambers: And what is the question?

Kate Schneider: Are you ready to go? And, I think it's a really generous question. I think it's actually a kind question. We're so anti that, we're so scared of death, and we've medicalized everything. Medicalized birth, medicalized death. It's a big fight to have it any other way.

Alex Chambers: We see that fight in Headland, in Ruth's struggle to stay human in her sterile hospital room. The drawings also have the touch of caring hands. It's not a book that was designed on a computer. I told Kate, having it all done in pencil gave it a kind of tenderness.

Kate Schneider: That's very sweet. There are some moments that are watercolor, and also that have a crumpled up-- I remember that I crumpled up pages, lay them flat, and drew over with charcoal.

Alex Chambers: Tell me about the decision to do it this way.

Kate Schneider: Comics weren't ever a part of my childhood. They weren't even a part of my teen-hood. First of all my parents just informed so much of my childhood with baby books and picture books, and the Snowman and Posy Simmonds, and all these British children's books, because my mom is British. So, I think that I was very inspired by British children's books. I think there's more vocabulary and more versatility in children's books. I think that we imagine children are delighted to see more worlds but I think we need it too. I really think we do. I don't know why we stop drawing, and going all over the place. I think Linda Barry said, "At some age around between ten and 12 we put down the pencil and never return." I think it's so tragic because we all start drawing when we're little, and then at some point the artist emerges in fourth or fifth grade, and everyone else is like, oh god, and puts down their pencil. [LAUGHS] I think we really need it.

Alex Chambers: I was asking what made you decide to do the book in this style.

Kate Schneider: I think that this was a story that I could live in for a long time, and it was a way that I could imagine making it. For example, I made a book, Dew Drop Diary, and that was more meticulous and rich, and I couldn't possibly sustain that over this many years. So there was just this combination of necessity and also, it was pleasurable. It was fun. The reward was making it, honestly.

Alex Chambers: That's cool, especially since you said you haven't really got any money for it.

Kate Schneider: That's exactly what somebody said. I can't remember who said it, but the act of writing better be the reward, because you're sure as hell not going to make any money from it.

Alex Chambers: Yes, for very few of us, even I think for the people who do end up making money. You want to have your work out there, and you want to know that it's affected people somehow.

Kate Schneider: Oh my god, yes. The people who are writing to me these days, I feel so moved by them. There was somebody on Instagram who said "My dad died of Alzheimers." There's just nothing like it to touch somebody and to feel like... I gave them a possibility into seeing, and they're a writer too. There's a lot that was possible because I'm not writing about my mom. I'm writing about my grandma, so there's a kind of artistic license that I think happens with a generation removed. But it was really beautiful, it was like a gift to me.

Alex Chambers: The book is hopeful. I didn't say this earlier, but it feels so hopeful at the end.

Kate Schneider: I'm glad, because I think a lot of people feel like, "Oh god, really, that's it?" [LAUGHS]

Alex Chambers: The end is a little surprising. I'm trying to decide about spoilers. It's not exactly a plot kind of book.

Kate Schneider: No it's really not. [LAUGHS] I think I did just say, so the tortoise gets smashed. [LAUGHS] Close to the end.

Alex Chambers: I'm just going to say, seeing her walk off into the colorful, beautiful night, feels like she's getting what she wants.

Kate Schneider: Yes. I do see it that way, I really do, because however you interpret that, whether it's to join her husband, whether it's to go off and just like, go into the next land; she's joined with her little bird and I think going from the land dwelling to the air is very... I liked that.

Alex Chambers: Thinking a little more about the style, was it hard to think about turning this into a published graphic novel in the style? Or were you thinking "This is what I'm doing"?

Kate Schneider: Yes, this is what I'm doing. I feel like I should say, because this isn't how everybody works, but I don't script things first. I think that things appeared to me in combinations of mostly images, and this is not advisable, but I would often make a thing, and be like "Oh, that's what I meant to do." Not because I made it but because that was not what I made. Scrap that. [LAUGHS] And I think that's the process of writing. But, when you're drawing it too, oh boy. It's like years and years down the road. So I think that there is like a two steps forward, ten steps backwards. [LAUGHS] Again, I was like, I wanted to live inside this story for a long time. It carried me through many chapters of my own life. Two heartbreaks [LAUGHS]. It was like "I'm going to do this, and I am going to finish whatever this is, and then I'll see if somebody wants it."

Kate Schneider: Maybe I will show it to Audrey. I'm starting to get excited about it. Maybe [LAUGHS]. I don't know. I think I will, as usual, I just have to let everybody have their experience with it. She's going to see herself in it, and that's okay, because she's in it. We all have different experiences of the same things anyway, so why not this?

Alex Chambers: We should do a follow up afterward.

Kate Schneider: OMG can I lock it in now?

Alex Chambers: Yeah.

Kate Schneider: Okay. [LAUGHS] Why not? I think she'll be proud of me. She's worked with me for-- I mean we don't work together anymore, but I worked with her for two years, and she'll be very proud of me, I think. I think I'd like to show her the page where she looks at the bird.

Alex Chambers: Yeah, that's a good page. Awesome, well Kate, thanks so much for doing this and for taking this time.

Kate Schneider: Thank you so much for having me and asking me these thoughtful questions.

Alex Chambers: It's been a delight.

Kate Schneider: Thanks.

Alex Chambers: Kate's book, Headland, is out now from Fantagraphic Books. It's time for a short break. When we come back Alicia Kozma tells us about a new organization that's helping Indie film maker find money. You could be a part of it too. This is Inner States, we'll be right back.

Alex Chambers: It's Inner States, I'm Alex Chambers. Alicia Kozma, our friend down the hill, and the director of the IU Cinema, came in last week for a mid-western movie segment. She had to wait a minute for me to get set up. There were no headphones in here.

Alicia Kozma: What kind of podcast studio is this?

Alex Chambers: I know. I like that you call it a podcast studio.

Alicia Kozma: That's what it is isn't it?

Alex Chambers: Most of the people in here do radio.

Alicia Kozma: Really?

Alex Chambers: And think of themselves as radio. And, I kind of like that you said pod-cast, because I feel like that's where things are going. And, I love pod-casts. I do want to say that I also love and believe in radio; and I'm not just saying that to my employers. Bu, I imagine plenty of your listeners are not listening to the broadcast version of this show. Anyway, more about pod-casts down the pike. In the meantime we've got a different Indie production culture to talk about. Specifically a new way for independent and aspiring movie producers to fund their work. It's not just about calling your dentist anymore. That will make sense in a minute. Here's Alicia.

Alicia Kozma: One of the things that comes along with movie news these days, is budgets. When we talk about films we often hear $258 million budget. $350 million budget. Or, this movie made $150 million at the box office. There's a way in which economics has become infused into just like public conversation around film making, contemporarily, that really hasn't existed before. These number are huge. They are so huge they are unfathomable. $350 million may as well be $14 billion; they're just both the same unimaginable numbers. Like, who cares how big they are? There's no real conception of what that means, even though we throw around these terms so frequently. It has come to a point where it seems like, if you want to make a movie, even if you want to make "a small movie", you're still working in tens of millions of dollars. But that's not really the case, or I should say it's not necessarily the case. When we talk about big budget film making, we're really just talking about any type of Hollywood film making. It's not just blockbusters that have giant budgets; although their budgets are certainly inflated.

Alicia Kozma: Multi-million dollar film making is really just the norm for Hollywood now. But thankfully there has always been a bit of a respite for that, in that we have always had independent film making in some way, shape or form. And one of the things that has made them truly independent has been their ability to fund films outside of a mainstream Hollywood financial scheme up. There is like this apocryphal kind of story that, back in the day in the 30s, it was dentists that you hit up. Dentists were the people that had extra money that you could go and ask to invest in your films. There's a truly phenomenal person named Ed Wood, who was also a truly phenomenally bad film maker; he's known for being a terrible film maker. I really recommend watching his "Plan 9 From Outer Space", and his big thing was that he would go to optometrists and dentists, and podiatrists, and hit them up for $5,000 here, $7,000 here. And that's how he would cobble together money to make his films.

Alicia Kozma: Even through the 90s, through the third independent film explosion, you had a lot of people financing films on credit cards, asking their family for money. Dropping out of college and using those tuition checks. Or again, still back in this like, dentist phase of just asking professionals who are also cinefiles, who maybe had some disposable income, to invest in their films for one of maybe 6000 producer credits at that point. Just because it feels good. It's just like a fundamental fact I think, that when people like film, they're willing to help film exist. And s, that was really the thing that under-girded that.

Alicia Kozma: Now, we've moved into a new type of independent film financing; one that is much more sustainable than just picking out your local dentist from the phone book.

Alex Chambers: Hoping your dentist has some extra cash.

Alicia Kozma: Much more sustainable, and it's thanks really to online crowd funding. Everyone's a little bit familiar with crowd funding already, but what happened in the late 2010s.

Alex Chambers: 2012 is the year Alicia is talking about.

Alicia Kozma: Was an on-line platform developed solely, purpose built, for film and television funding. And, purpose built for film and television funding for people who did not already have big industry connections. People who weren't benefits of nepotism. People who didn't have the dentist with the deep pockets in their corner. Just like every day people who wanted to be story tellers, and who wanted to be film makers. This is a platform called Seed and Spark. So it is open for anyone to use, and it's a crowd funding page, but that crowd funding page also acts like a registry system. It doesn't just say "I need $10,000 to make my movie. Please help me and I'll send you a DVD in the mail once it's done." Like a lot of other crowd funding platforms aren't built for film making do. Something like a Go Fund Me or a Kick-starter, or Indiegogo or something like that. It tells you exactly what the film's budget is, exactly what that money is going to. Exactly how much they have and what they need, and it allows individuals to contribute at a level that's comfortable to them, but also let's them see how that makes an impact. How that makes a difference.

Alicia Kozma: It's one thing to say I need $1,000 to edit my film. It's much different to say, "Hey I need an editor for an hour, it's $150." You can actually see where that money is going.

Alex Chambers: You can pay for an hour of editing.

Alicia Kozma: You can pay for an hour of editing. And an hour of editing is a tremendous help. One of the other nice things about Seed and Spark is that, if you don't have money but you have equipment, or talent, you can donate that too. So it's not just about open your wallet. It's "Do you have a camera? Are you an editor? Do you have this piece of AV equipment that I need?" and you're in my area, you can loan stuff out to them, or you can loan services out to them too. So it's a much more communal way of working, that's not totally dependent on how much money you can give somebody. Or, lump sum fund-raising, essentially. And, the really great thing about it, is that because it's purpose built for film and television, you can watch the thing on the platform, once it's done.

Alex Chambers: Very nice.

Alicia Kozma: So it's not just like you're donating into the void or into the ether, you can see this thing once it's finished.

Alex Chambers: It's also a streaming service.

Alicia Kozma: It's also a streaming service, but only for the backers. They raise an average of $14,000 per project, and about 75% of their projects get totally funded. It charges a much lower commission than other crowd funding sites. And it also offers the opportunity for backers to cover the commission.

Alex Chambers: To co-- wait.

Alicia Kozma: So any crowd funding site takes a commission of the money raised.

Alex Chambers: Oh, I see. The commission to the site itself.

Alicia Kozma: To the site, yes. So Kickstarter takes like, eight percent, Indigogo takes something like seven or eight percent. GoFundMe is like the wild west. Who knows what they do. Seed and Spark takes just five percent, and they have an option to say, "No, I want to cover that five percent, so this film maker doesn't have to pay anything."

Alex Chambers: Nice.

Alicia Kozma: So one of the things it's done is really allowed an entirely new cadre of film makers who haven't had access to the networks; haven't had access to the equipment or the funds to get their stories out there. A lot of those have been film makers of color, that simply have not been let into the system; into the pipeline that lets you produce this type of work. So, it's been a tremendous help in really bringing different types of stories, different types of storytellers, and then just different types of films that we get to see at the end of the day. They've done a phenomenal job, and I have, maybe unsurprisingly, an example from the mid-west...

Alex Chambers: Glad to hear it.

Alicia Kozma: ...of someone who is utilizing Seed and Spark. Caitlyn Johnson is a director and a writer and producer, who's originally from the south side of Chicago. She's got no-one in her family who's in the film business. Not even close. It's something that was a dream of hers, and she's been out there grinding the pavement, and blood, sweat and tears'ing, until she's able to do what she wants to do. Her work is really specifically focused on providing storytelling outlets for marginalized and under-served communities. She's invested in those communities being able to tell their own stories; specifically through independent film making, as a way to not have to compromise either the stories or the vision through dentists money, or through the Hollywood machine, or something else.

Alicia Kozma: A key ingredient to the work she has produced and is in the process of producing, is being able to fund that communally, in order to maintain the integrity of the project. Her first foray into directing was in 2018, where she co-created and directed a web series that went onto tremendous acclaim and won a bunch of awards. It's called Seeds, and it was a really great kind of introduction to her vision of how alternative story telling can go, and what it means to not have to compromise your vision. And, whose stories you can tell when you don't have to compromise those visions. So, Seeds follows four young black women in Chicago, just trying to navigate their life and figure out how to exist, in spaces where they're welcome and spaces where they're not welcome. How to exist and interact with one another. It is both universal and personal at the same time. It's a great series, and it was her first step into being able to realize her vision.

Alicia Kozma: She is now working on a short film; she's in post-production and her short film is titled Bad Blood. She is building on the work that she did in Seeds and Bad Blood, which is a coming of age story that examines fear and shame, and autonomy, but specifically the construct of black sisterhood. And specifically pulling from her Chicago roots. She's filmed, she's good to go, but she's in post-production now, and one of the things maybe that we just don't talk about in general in film is post-production. If you produce a podcast you know all about post-production; it's when you edit everything and make it sound good.

Alex Chambers: Like you've done all the filming.

Alicia Kozma: You've done all the filming, principled photography is finished. Your actors have gone home, your sets are closed down, you have a bunch of raw material in front of you. It has to be edited, it has to be color corrected. You need sound tracks, you need sound design, you need credits. You need to re-shoot stuff that didn't work in the first place. It's like a whole other phase of film making, and most of that second phase of film making, unlike principle photography, is not done by directors. It's not done by cinematographers. It's done by a whole new roster of professionals. Sound design is a really specific skill. Editing; some directors are editors, but editing is a really specific skill. Visual effects, if you have that, these are honed craft skills that is a very specific toolbox, and it often includes bringing other people into the mix. One of the great things about the independent film community is that, there are lots of people within it who are versatile. So you could have someone like Caitlyn who is a director, and a cinematographer. She can do both. But no one person can do everything, so she still needs an editor, and specifically what she's working on right now is sound design.

Alicia Kozma: And so, she's taking advantage of Seed and Spark to help finish Bad Blood, and get this work out there, and get this work shown. So, for people who are interested in supporting new stories and new visions, and an entirely new crop of film makers coming up, like Caitlyn, Seed and Spark is a great place to go to fund this. And it isn't the type of thing that needs you to put down a four figure gift. 50 bucks in the independent film world goes a long way; that can be a half hour of editing. You know what I mean? That is a big deal. And again it allows more autonomy for people who love film, or even like it, but are invested in having a vibrant film culture around them, and being able to see different stuff and hear different stories. You can be an active part of that through platforms like Seed and Spark, and supporting film makers like Caitlyn on it.

Alex Chambers: It's like the democratic promise of the internet, that for the most part has fallen apart.

Alicia Kozma: Yes. It's like what we thought Internet 1.0 was going to be. [LAUGHS]

Alex Chambers: I mean in the sense that you're not just depending on your dentist and your doctor.

Alicia Kozma: It also brings people together that may not have normally been brought together, and that only ever ends up in a collision of really cool new ideas, that would not have happened before, which is just so exciting. It's so nice to know that despite all these overblown budgets and multi-million dollars, there are still people out there that understand the value of a dollar, and can really make it work. And they make it work into a really good thing.

Alex Chambers: Awesome. That's great Alicia. Thanks so much.

Alicia Kozma: Thanks. Appreciate being back.

Alex Chambers: Glad to have you, always.

Alex Chambers: Alright, that was Alicia Kozma, director of the Indiana University Cinema, and this has been Inner States; a radio show and pod-cast from WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana. If you have a story for us, or you've got some sound we should hear, let us know at WFIU.org/innerstates. Speaking of found sound, we've got you a quick moment of slow radio coming up, but first, the credits. Inner States is produced and edited by me, Alex Chambers, with support from Eoban Binder, Aaron Cain, Mark Chilla, Michael Paskash, Payton Whaley and Kayte Young. Our Executive Producer is John Bailey. Special thanks this week to Kate Schneider and Alicia Kozma. Our theme song is by Amy Oelsner and Justin Vollmar. We have additional music from Airport People. Alright, time to take a breath and listen to a place...

Graduate Student Workers: [NOISE OF STRIKING GRADUATE STUDENT WORKERS]

Alex Chambers: That was the sound of graduate student workers at Indiana University, striking earlier this week, to get recognition of their union. Thanks to Kayte Young for that recording. Until next week I'm Alex Chambers, thanks for listening.