pc: pixabay.com

This week, we’re exploring the theme of ornamentation in classical music, in a show we’re calling “Fandangle.” Collect all of your bits and bobbles, your frills and finery, because this playlist will be full of frippery!

Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus (1756-1791) Piano Sonata No. 11 in A Major, K. 331 Andante grazioso (Theme and Variations) This sonata in A major is among Mozart’s most beloved piano works. Instead of starting out with a movement in sonata form, typical of the genre, the first movement of this sonata does something different. It’s a set of variations on a lovely A major theme, with a lilting 6/8 siciliana rhythm. Mozart was renowned for his ability to improvise and ornament melodies, and one spectator wrote that “One had only to give him the first subject which came to mind for a fugue or an invention: he would develop it with strange variations and constantly changing passages as long as one wished.” The form that Mozart improvised in became known in the Classical era as the “theme and variations” form. A short musical idea, often of eight or sixteen measures, is reworked through different styles and ornamentations. It is likely that many of Mozart's written-out theme and variations, such as the piece we just heard, are basically transcriptions of his improvisations.

Tchaikovsky, Peter Ilyich (1840-1893) Varations on a Rococo Theme, Op. 33 When Tchaikovsky composed his “Variations on a Rococo Theme,” he used the term “rococo” to describe an original melody written in the classical style of Mozart, whom he greatly admired. Rococo is most often used to describe an interior decorative style most popular in France in the late 1700’s. Characterized by extensive (and some would say overuse) of curvilinear ornament inspired by shells, flowers, pastoral themes and bizarre combinations of humans and animals, the style has no real musical equivalent. However the grace, frivolity and natural lightness expressed in Rococo art is very much present in Tchaikovsky’s nine variations for cello and orchestra, written for cellist Wilhelm Fitzenhagen who was a fellow professor at the Moscow Conservatory. Fitzenhagen extensively altered the piece over subsequent performances, changing the order of the variations, splicing passages, and eventually eliminating the eighth variation altogether.

Donizetti, Gaetano (1797-1848) Luccia Di Lammermore, Mad Scene Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, based on a novel by Walter Scott, depicts the tragic fall of the Lammermoor family. In act I, Lucia must marry Lord Arturo Bucklaw, to save the family fortunes. Lucia is secretly in love with Edgardo of Ravenswood and the arranged marriage has a destabilizing effect on her already fragile emotions. On her wedding night, Lucia murders Arturo and then performs the famous “Mad Scene.” She sings the aria we heard moments ago before taking her own life as the curtain falls on the scene. Donizetti was a leading exponent of the Bel Canto style of Italian opera in the early 19th century, which is especially present in Lucia’s music. Meaning “Beautiful Song” in Italian. Bel Canto singing emphasized the brilliance of performance and sound over dramatic expression, often using wildly virtuosic ornaments or coloratura, as we just heard.

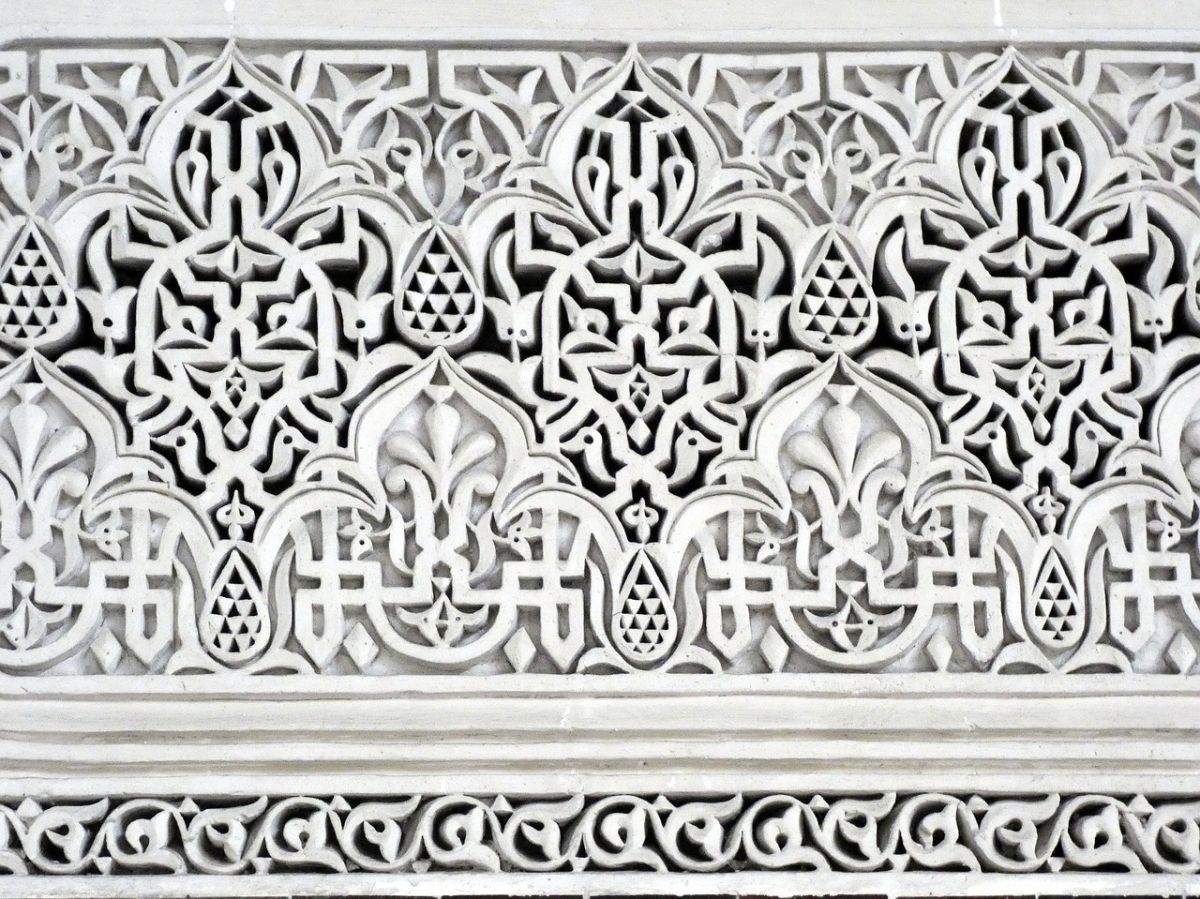

Debussy, Claude (1862-1918) Deux Arabesques This very early piano piece by Debussy, one of his most popular, is a delicate expression of the French composer’s fascination with the exotic East. The word “Arabesque” first emerged in the world of architecture, referring to a decoration of intricate, swirling lines often found on many Middle Eastern buildings. Such swirling lines were also a hallmark of the Art Nouveau movement, an architectural style popular in Europe in Debussy’s time. It’s not hard to see how the architectural concept of swirling lines could also be easily applied to the world of music—Debussy’s first Arabesque swirls and twirls with these decorative flourishes. After all, there is that well-known aphorism, often credited to Goethe that says “music is liquid architecture. Architecture is frozen music.”

Tartini, Giuseppe (1692-1770) Sonata in G minor, "Devil's Trill" Giuseppe Tartini gained a reputation as one of the finest violinists in the world, and was the first documented owner of a Stradivarius violin. We just heard perhaps his most famous work, which he titled “The Devil’s Sonata.” Tartini dreamed he had made a pact with the devil, and asked if the devil might play his violin. What emerged was a sonata Tartini described as “so beautiful, performed with such mastery and intelligence,” that he wanted to possess it. He attempted to write out the music he heard in his dream, giving birth to the piece we now know as “The Devil’s Trill.” Legends about Tartini's violin playing would continue to follow him even after his death in 1770. It was believed, for example, that he had a sixth digit on his left hand which allowed him to play more skillfully than any other violinist in the world.

Couperin, François (1668-1733) Allemande L'Auguste François Couperin was one of the greatest performers and composers of the French Baroque. Born into a gifted musical family, he was a particularly skilled solo performer at the keyboard, and earned the nickname "Couperin the Great" or "Couperin Le Grand" to distinguish himself from the rest of his family. Though his compositions were greatly desired by the French elite, Couperin faced a major social predicament among his admirers: he adored Italian music, and preferred to compose in the Italian style, even though the French Baroque style was highly distinctive, incorporating its own set of ornaments,called agréments, that were more florid than those heard in other music. Couperin published his first solo pieces under an Italian pseudonym and though the pieces were well received, the French intellectual elite were outraged when they discovered his trickery. They argued that the Italian tradition of writing music for its own sake was artificial and not true art. Couperin appeased them by giving his future pieces titles that referenced French subjects and stories, such as Allemande l'Auguste

Bantock, Granville (1868-1946) Celtic Symphony: Allegro con spirito Classical music is not the only tradition that has preserved the use of ornaments to embellish melodies. In fact the practice is drawn from much older folk traditions. Especially in celtic music for example, a chief tennant of the style is the use of ornaments such as rolls, graces and cuts to add excitement and flavor to dance music. Many composers have drawn inspiration from celtic music, but they often remove the traditional ornaments so as to better translate into classical style. That was not the case with English composer Granville Bantock, who included the traditional ornaments when he borrowed themes from Scottish folk tunes for his symphonies. His Celtic Symphony borrowed from a scottish air called Sea Longing that was popular on the Hebrides islands, and the final movement which we just listened to, incorporates the ornaments and rhythms of the celtic reel, a fast paced dance in duple time, and one of the most popular dances in celtic folk music.

Ireland, John (1879-1962) Decorations: The Island Spell The Englishman John Ireland was born in Cheshire in 1879, where he had a lonely, unhappy childhood plagued by the early death of his parents. He entered the Royal College of Music in 1893, where he initially studied piano and organ and later composition. A visit to the Channel Islands in 1912 inspired this set of three pieces for solo piano, titled “Decorations.” In this first movement, “The Island Spell,” Ireland expresses an almost mystical response to the beach and the sound of bells. Ireland’s music often has an introspective nature and tends towards spiritual longing, perhaps influenced by his friendship with the horror writer and mystic Arthur Machen. An excerpt from one of Machen’s stories even adorns the top of the score to the third piece in this piano set, describing secret rituals and occult ceremonies.

Paper Lace: The Night Chicago Died The Nottingham-based pop group Paper Lace achieved success in both the UK and the US when their single “The Night Chicago Died” charted at #1 in 1974. Inspired by the activity between gangsters and policemen in Prohibition-era Chicago, the lyrics describe a fictitious shootout with the Chicago Police Department and the Al Capone Syndicate. Paper Lace had previously been successful with “Billy Don’t Be A Hero,” another charting hit in the UK, but when the American pop group Bo Donaldson and the Heywoods cover of this song reached #1 in the US, Paper Lace had to pen another single, and finding that American listeners assumed “Billy Don’t Be a Hero” was about the Civil War, they turned once again to American history to write their next hit.