pc: pixabay.com

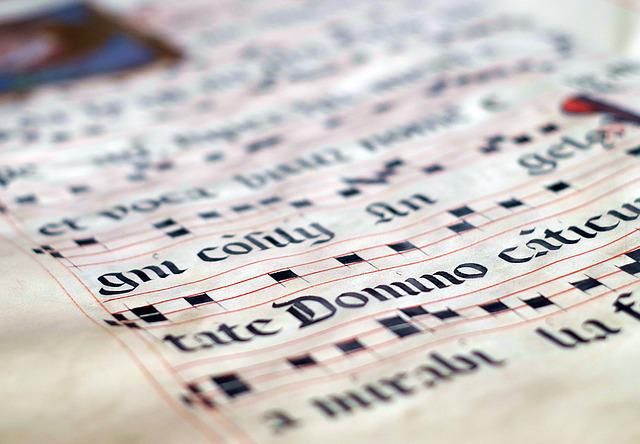

This week, we quizzed on music from before 1800 in partnership with the Bloomington Early Music Festival. Enjoy this collection of composers, both poular and obscure, who wrote music during the Renaissance and Baroque eras.

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The Four Seasons: 'Spring' in E, Op. 8, No. 1, RV 269 “Springtime is upon us.” Thus begins the poem that opens the first of Vivaldi’s famous “Four Seasons” concertos. It continues: “The birds celebrate her return with festive song, and murmuring streams are softly caressed by the breezes. Thunderstorms, those heralds of Spring, roar, casting their dark mantle over heaven, then they die away to silence, and the birds take up their charming songs once more.” In the original publication of the Four Seasons, a sonnet was printed alongside each concerto. Although the author of the poems was not credited in the original publication, scholars have good reason to think it might’ve been Vivaldi himself. Specific indications, printed in the score itself, let the performers know what’s happening in the “plot” of the piece - singing birds, sudden thunderstorms, and rustic bagpipes all appear directly in the manuscript!

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 in B-flat, BWV 1051 Bach wrote six concertos for the Margrave of Brandenburg, Christian Ludwig. Bach was mostly likely seeking employment from the Margrave, but didn’t receive any. Having assumed that Christian Ludwig would have plenty of musicians in his Berlin ensemble, Bach had composed the concertos for seventeen performers, the exact number he had at his disposal while director of church music in Köthen. Unfortunately the Margrave was not much of a patron of the arts, and did not employ enough musicians to perform the concertos. Instead, the manuscript (which Bach, rather than a copyist, had prepared himself) was squirreled away in a private library in Brandenburg and not rediscovered until 1849.

John Dowland (1562-1626) Three Galliards English composer and lutenist, John Dowland was a Catholic at the wrong time in English history. From 1598 to 1606 he served as the court lutenist to the popular King Christian IV of Denmark, to whom one of tonight’s selection was dedicated. Although Dowland is often remember for his melancholy Lachrimae, or Seven Tears, Pavan, he also wrote numerous light-hearted dance tunes. One of Dowland’s favorite dance forms was the lively triple metre dance, the galliard, a form that was also favored by Queen Elizabeth I. Although they shared religious differences, Dowland still dedicated two of his works to Queen Elizabeth, the first, Queen Elizabeth, her Galliard and the second The Queen’s Galliard, which was written in the unusual key of B flat minor, perhaps reflecting the personal difficulties he had with her Royal Highness.

Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) Chiome d'oro, bel thesoro, SV 143 At first glance, Monteverdi’s Seventh Book of Madrigals might not seem like madrigals at all, at least not in the way he wrote them years earlier. Instead of five-voice works, the madrigals here are typically for one or two voices with accompaniment, more resembling the newly emerging operatic style rather than the older choral style. In fact, he titled the book “Concerto” and opened the collection with an instrumental sinfonia, furthering the comparison to opera. Like in Monteverdi’s other madrigals, he sets the works of famous Italian poets. Many of book seven’s poems are by Guarini. Monteverdi dedicated this work to Duchess Caterina of Mantua, in hopes that she would reward him handsomely with a pension. However, Caterina thought it was worthy of a different kind of treasure. Instead of money, she gave him… a necklace. Valuable, perhaps. But not exactly what Monteverdi had in mind.

Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672) Historia der Auferstehung Jesu Christi, Op. 3, SWV 50: Conclusion One of the most important figures in the Lutheran oratorio tradition before Bach was seventeenth-century composer Heinrich Schütz. History of Christ’s Resurrection was one of his masterworks. In the interplay of arias, choruses, and evangelistic recitative, we already hear elements of the tradition that Bach would inherit. As was common at the time, religious oratorios would only occasionally include text from just one Gospel. It was more common to jump around, taking the most dramatic moments from various sources. At the time of its performance, this epic work would have sounded completely modern. When Schütz arrived at court in Dresden, where he was hired as music director in 1617, he found old-fashioned performing traditions for Easter that dated back to the end of the 15the century. It is unclear if Schütz was specifically commissioned to update the court’s Easter music, but he was given the freedom to do so, and produced, along with his Christmas Oratorio, two of the 17th century’s most innovative religious masterpieces.

Tomas Luis de Victoria (1548-1611) Magnificat on the Sixth Tone The Counter-Reformation of the late-Renaissance was a time of great change in sacred music. This was fueled by mandates issued by the Council of Trent against polyphony, instrumental accompaniment and ornamentation in church music. Composers would have found these demands highly oppressive, but they were not strictly enforced across Europe, and thus some of the most beautiful and popular sacred music of the Renaissance was produced during this time. In Spain, composer Tomás Luis de Victoria was hailed as the “Spanish Palestrina” for his vast output of sacred music, written in a style that glorified the Catholic liturgy while maintaining artistic appeal. His Magnificat on the Sixth Tone would have been performed during Vespers, the evening prayer service. The Sixth Tone refers to one of eight modal Psalm tones, a melodic recitation formula used in the composing of early chant music.

Elisabeth-Claude Jacquet de la Guerre (1665-1729) Suite in d, Cannerie, Chaconne Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre was a bona fide child prodigy, and one of the few female composers to achieve true superstar status during the Baroque era. Born into a family of musicians, she performed her first concert for Louis XIV [14TH] at the age of five. Throughout her life, she enjoyed a successful career as both a composer and a virtuoso harpsichordist. When she was only 26 years old, Titon du Tillet recognized her talent with inclusion on his Mount Parnassus, where he placed her second only to Lully! Her harpsichord works were among the few pieces for the instrument that were printed in France during the 17th century. Upon her death in 1729, a stamp was placed on her portrait that states in French, “I contended with the greatest of musicians,” a fitting honor for one of France’s earliest leading ladies in the realm of music.

Johann Christoph Graupner (1683-1760) Overture in C for Three Chalumeaux Many French orchestras in the Baroque era featured an early version of the clarinet, called the chalumeau. The chalumeau was one of several reed instruments that were heavily favored by the French aristocracy in the Baroque era, who romanticized the instrument for its association with shepherds and pastoral folklore. The chalumeau originally came in several sizes, like a recorder consort, with the bass version of the instrument matching the size of the modern clarinet. While the clarinet is often seen as an “improved” chalumeau, it did not render the instrument obsolete. There were unique parts for both instruments in the Baroque orchestra well into the 1700’s, with groups of chalumeaux covering the lower register and providing orchestral color while the clarinet was used for louder and higher virtuosic playing. As the chalumeaux gained popularity, it spread to Germany where composer Christoph Graupner heard the instrument in the pit of the Hamburg Opera where he was a harpsichordist. Graupner was so taken with the chalumeau that many of his compositions feature a solo part.

Enigma (1990) Sadeness Part. 1 Virgin Records released its first compilation album of ambient and new age music in 1994. Titled Pure Moods, the compilation featured international artists who worked in an emerging aesthetic of lush synth pads, atmospheric drum beats and sampled recordings of world music. The album had several top-selling tracks including “Sadeness” by the German music project Enigma. Michael Cretu is the musician behind Enigma, and had been producing albums for his wife, the pop singer Sandra, before becoming inspired to make music with mystic and experimental aspects. Many tracks by Enigma feature Gregorian chant, which is noteworthy because the same year that Pure Moods was released, a separate compilation album of chant by the Spanish Benedictine Monks of Santo Domingo de Silos was wildly successful. Marketed as a balm to the stress of modern life, the album re-release sold 6 million copies worldwide and started a mania for Gregorian chant which lasted the rest of the decade.