Ernie Pyle was one of the nation’s most popular newspaper columnists throughout the 1930s and ’40s. He gained fame as a celebrated travel columnist for the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain during the Great Depression. He then achieved worldwide acclaim as a war correspondent during World War II.

The following are a sample of Pyle’s most popular columns, both from his time as a roving reporter – where he wrote under the title “Hoosier Vagabond” – to several excerpts from his most compelling war columns.

Pyle excerpts printed with permission from the Scripps-Howard Foundation

America

War Columns

The Dust BowlKansas

It was only at night, when you were alone in the heat and unable to sleep, that the thing came back to you like a living dream, and you once more realized the stupendousness of it. Then you could see something more than field after brown field, or a mere succession of dry water holes, or the matter-of-fact resignation on farm faces. You could see then the whole obliteration of a great land, and the destruction of a people and long years of calamity for those of the soil, and the emptiness of the life that knows only struggle and ends in despair. I had seen a great deal of this in the past few years. Sometimes at night when I was thinking too hard I felt that there was nothing but leanness everywhere, that nobody had the privilege of a full life. Of course I was wrong about that.

I had just seen too much of the ruination of our great land. The beautiful valleys and hillsides of Tennessee washing away to the ocean, leaving a slashed and useless landscape. The raw windy plains of western Kansas, stripped of all life, a onetime paradise turned into a whirlpool of suffocation. And the vast rolling Dakotas, where huge herds once grazed with the freedom of birds, now parched and cramped and manhandled by man and the elements into a bed of coals.

Boxcar BeautyAlbuquerque, NM

Irene Fisher lived in a boxcar four miles north of Albuquerque, New Mexico. Irene was no tramp, and she lived in a boxcar on purpose, because she was arty like the people at Santa Fe.

She bought an old refrigerator car from the railroad – paid forty dollars for it, and paid a trucker forty dollars to get it out there. Then she went to work. In one end she built a bunk, crosswise, the kind of bunk ship’s officers have in their cabins. Beneath it, instead of drawers, was another bed which slid out. This was the “guest room.” From this end of the car to beyond the big doors in the middle was one room. Then there was a partition, with a door. Next was the kitchen, with a coal stove for heating. And beyond that, in the far end, was the bathroom. The thing didn’t seem cramped at all.

You’d be surprised how homey a boxcar can be. Irene had electric lights and running water. She had pictures on the walls, and bookshelves, and rugs, and a table and a chaise longue. She said the only thing wrong was that the railroad had carefully painted out all the bawdy poems that knights of the road always write on the inside of boxcars.

Sights on the SoundSeattle, WA

The prairies are all right. The mountains are all right. The forests and the deserts and the clear clean air of the heights, they’re all right. But what a bewitching thing is a city of the sea. It was good to be in Seattle – to hear the foghorns on the Sound, and the deep bellow of departing steamers; to feel the creeping fog all around you, the fog that softens things and makes a velvet trance out of nighttime. It was good to say to yourself, “Out there through the mist is China. Out there the dirty freighters go, and the fishermen for Alaska.” And it was good to hear the tall and slyly outlandish tales that float up and down Puget Sound…

Once upon a time there was a tugboat on the Sound, dragging behind it a long tow of logs. There was no special hurry, so the tugboat was hardly moving at all. Furthermore, it was using its leisure time to run some oil tests on its new diesel engines. The engineer had several five-gallon cans of different brands of oil. He would let the engine run until it exhausted one can, then cut in a different brand, start the engine, and plow ahead again.

All this left the captain bored, and with nothing at all to do. Furthermore, his feet hurt. He stood sadly on the deck, watching the shore which hardly moved at all, and now and then taking a jealous look at the water around him. It looked so cool. If he could only put his aching dogs into it. Finally he took off his shoes and socks, sat down on the low rail, and hung his feet over the side. Lordy, it felt good!

Champion Soda JerkerEvansville, IN

Harold Korb, of Evansville, was the champion soda jerker of the United States, and he didn’t take the honor lightly. He was proud and serious about it. It was more as though he had been given a medal by a scientific society in recognition of years of research. And the funny part about it was that Harold Korb wasn’t a soda jerker at all, and never had been. He was an ice-cream salesman. But he sure knew how to make a chocolate soda – only I shouldn’t say it that way. You never make a soda or jerk a soda, or mix a soda. What you do is “build” a soda. Korb’s great distinction came at Cincinnati, at a convention of sixty-six ice-cream salesmen from all over America. These salesmen have to be better soda jerkers (builders) than the jerkers themselves, because it is part of their job to tell the jerkers how to do it. Well, at this convention, every salesman had to build a soda. The judges didn’t sample the sodas; they just watched the building process. And it was such a beautiful sight to watch Harold Korb build a chocolate soda that even before he had finished they told him he was the winner.

His prize number was called the Mellow-Cream Chocolate Soda. Here’s how he built it: he put in an ounce and a half of chocolate syrup, then two soda spoons of stiffly whipped cream; he stirred them up very thoroughly and discarded the spoon; he shot a very fine stream of carbonated water into the glass until it was three-quarters of an inch from the top (didn’t dare stir it any more); then he plied (yes, plied) two No. 24 dips of ice cream, one gently on top of the other, so it would stick up on top of the soda and the customer would see it and say, “Oh, goody!” I laughed and said, “Well, you’re really a big shot now, aren’t you?” Korb laughed too, but he said, “I’ve never been anything but a big little shot to Harold Korb.”

His Name Rings a BellAlbany, NY

We were sitting in a hotel room in Albany one night when all of a sudden the whole town seemed filled with “Home on the Range” coming from nowhere. We looked under the beds and in the bathroom and out of the window, and finally decided it was coming from the top of the City Hall tower. It was “Home on the Range” on bells.

Now I’ve always hated music that comes from bells in tall spires. It is always a mournful hymn or something far too classical for my hotcha tastes. But when you hear bells playing “Home on the Range,” that’s different. I said to myself, “I’ll have to find out about this guy.” Next day I tracked down the heretic. His name was Floyd Walter. He was a big fellow with a short pompadour, and he was as affable as his music.

“What makes you play human on carillon?” I asked. “Never heard of such a thing.”

So he told me what he’d told a convention of carillon players, where they talked about nothing but Beethoven and hymns. “I don’t know who is paying you fellows,” he told them. “But I know who’s paying me – it’s the taxpayers. And if the taxpayers of Albany want ‘Lazy Bones,’ that’s what they’re going to have.”

Celebrating HopeWarm Springs, GA

Warm Springs is seventy-five miles south of Atlanta and not far from the Alabama line. It is in heavily wooded pine country, very rolling, and about as beautiful as you will find in the South.

This is the only sanitarium in America that accepts nothing but poliomyelitis cases – “polio” for short. Even the patients refer to each other as “polios.” The place seemed to me more like a college than an institution. In fact, the officials called the grounds “the campus.” You saw patients around everywhere – in wheel chairs, on crutches, even on wheeled stretchers. From their faces, you would never have known they were invalids; the tragedy of polio seemed never to show in the face. Only withered limbs and the braces on legs told the story. Yet, although polios are in pitiful shape, there is nothing pitiful at all about the atmosphere at Warm Springs – and I believe that is as important as all the scientific treatment. Back home a stricken individual gets to brooding, drops out of the stream of life, and is often the victim of melancholia, thinking of himself as a hopeless cripple. But at Warm Springs that feeling is almost invariably wiped out. Patients see others of their kind all around, having a good time. “Polio” ceases to be a hushed word, spoken with self-pity. They make up songs about themselves, such as “From the tops of our heads to the tips of our toes – we’re paralyzed.” Back home they were invalids. At Warm Springs they are human beings.

President Roosevelt came to Warm Springs two or three times a year. Everybody there loved him, and his visits were always high spots. His little settlement of private cottages was about a mile from the hospital grounds, back in the woods. Neat signs pointed to the “Little White House.” His own cottage was a spreading six-room house with two baths, on the slope of a hill, nearly hidden by pine trees. There were also a guest house and a house for servants. When the President was not there, the houses were closed tight, and Georgia National Guardsmen stood watch in a little sentinel house out front.

A Dreadful MasterpieceLondon, England

For on that night this old, old city – even though I must bite my tongue in shame for saying it – was the most beautiful sight I have ever seen.

It was night when London was ringed and stabbed with fire.

About every two minutes a new wave of planes would be over. The motors seemed to grind rather than roar, and to have an angry pulsation like a bee buzzing in blind fury.

Into the dark, shadowed spaces below us, as we watched, whole batches of incendiary bombs fell. We saw two dozen go off in two seconds. They flashed terrifically, then quickly simmered down to pinpoints of dazzling white, burning ferociously.

These white pinpoints would go out one by one as the unseen heroes of the moment smothered them with sand. But also, as we watched, other pinpoints would leap up from the white center. They had done their work – another building was on fire.

Dedicated SoldiersAlgiers, Algeria

I am living at this airdome for a while. It can’t be named, although the Germans obviously know where it is since they call on us frequently. Furthermore, they announced quite a while ago by radio that they would destroy the place within three days.

I hadn’t been here three hours till the Germans came. They arrived at dusk. And they came arrogantly, flying low. Some of them must have regretted their audacity, for they never got home. The fireworks that met them were beautiful from the ground, but must have been hideous up where they were.

They dropped bombs on several parts of the field, but their aim was marred at the last minute. There were no direct hits on anything. Not a man was scratched, though the stories of near misses multiplied into the hundreds by the next day.

One soldier who had found a bottle of wine was lying in a pup tent drinking. He never got up during the raid – just lay there cussing at the Germans.

“You can’t touch me, you blankety-blanks! Go to hell, you so-and-so’s!”

When the raid was over he was untouched, but the tent a foot above him was riddled with shrapnel.

Another soldier made a practice of keeping a canteen hanging above his head. That night when he went to take a drink the canteen was empty. Investigation revealed a shrapnel hole, through which the water had run out.

Everybody makes fun of himself – but keeps on digging. Today some of those trenches are more than eight feet deep. I’ll bet there has been more wholehearted digging here in two weeks than the WPA did in two years.

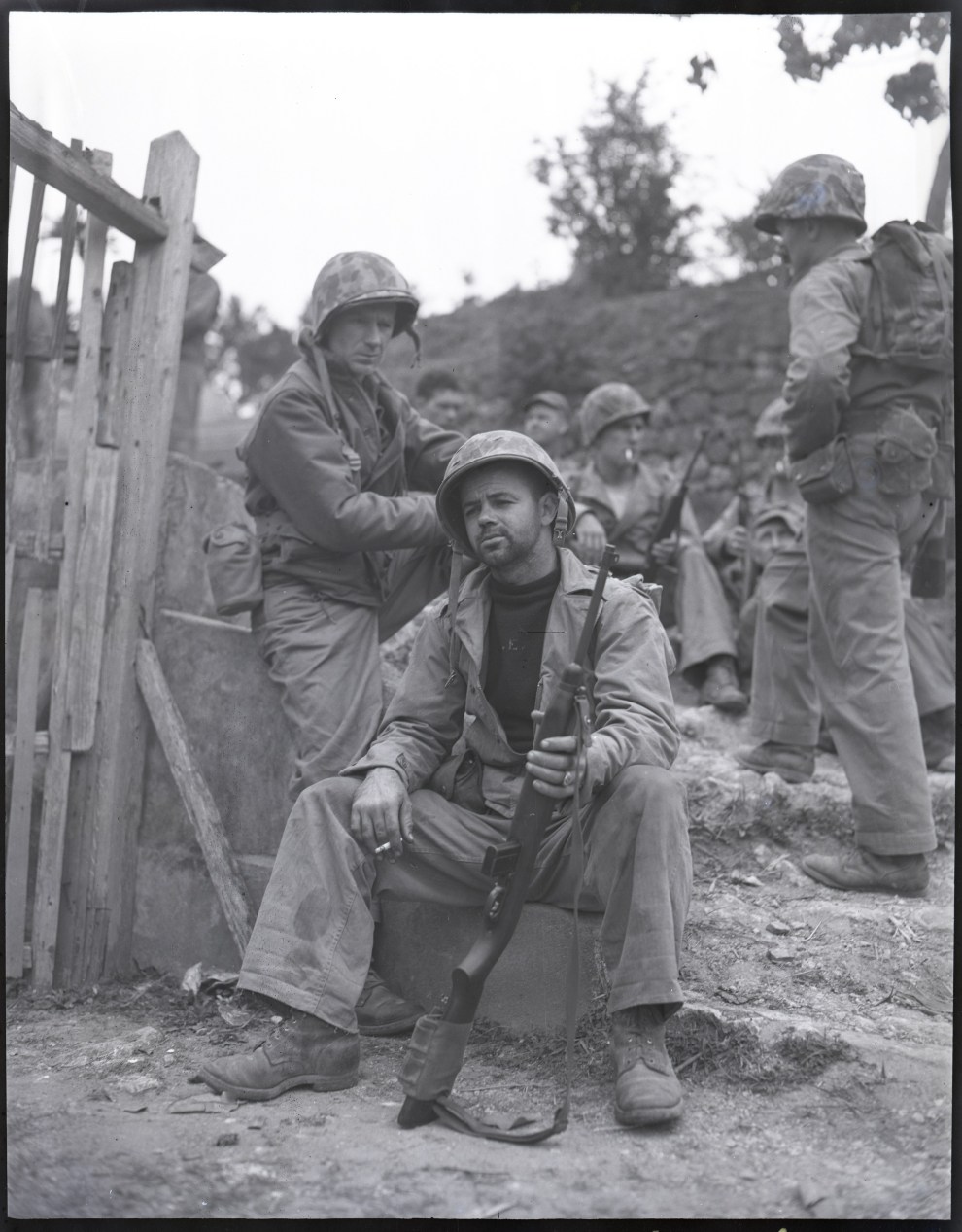

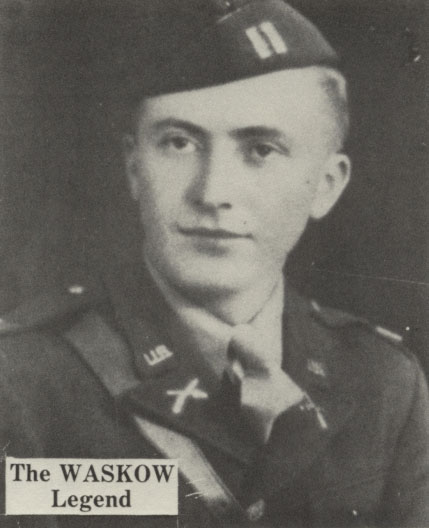

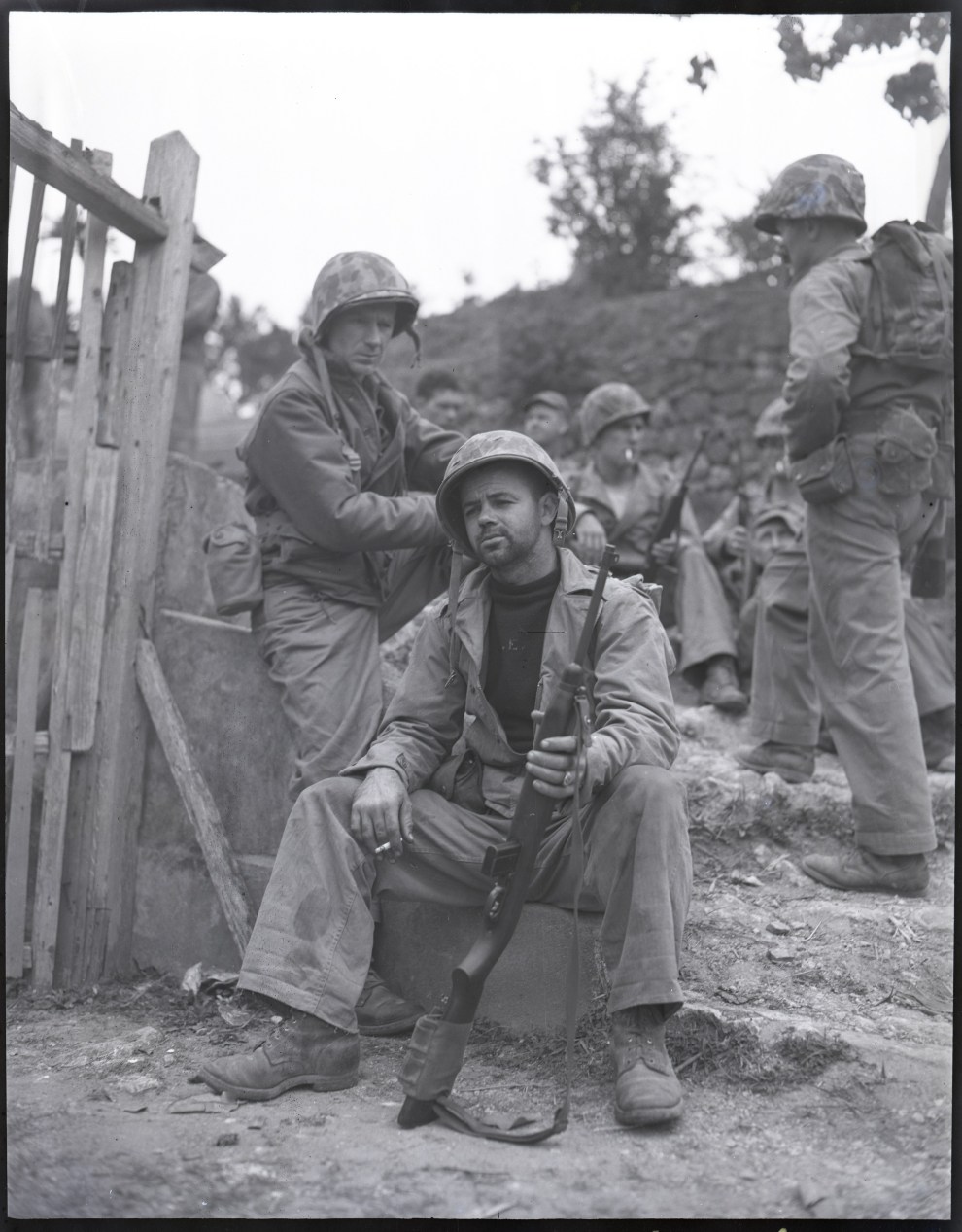

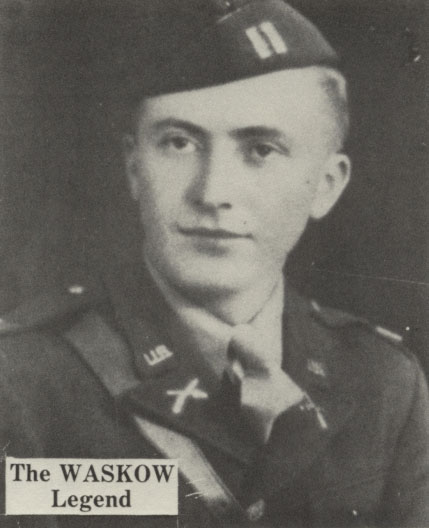

The Death off Captain WaskowSan Pietro, Italy

In this war I have known a lot of officers who were loved and respected by the soldiers under them. But never have I crossed the trail of any man as beloved as Capt. Henry T. Waskow of Belton, Texas.

Capt. Waskow was a company commander in the 36th Division. He had led his company since long before it left the States. He was very young, only in his middle twenties, but he carried in him a sincerity and gentleness that made people want to be guided by him.

“After my own father, he came next,” a sergeant told me.

“He always looked after us,” a soldier said. “He’d go to bat for us every time.”

“I’ve never knowed him to do anything unfair,” another one said.

I was at the foot of the mule trail the night they brought Capt. Waskow’s body down. The moon was nearly full at the time, and you could see far up the trail, and even part way across the valley below. Soldiers made shadows in the moonlight as they walked.

Dead men had been coming down the mountain all evening, lashed onto the backs of mules. They came lying belly-down across the wooden pack-saddles, their heads hanging down on the left side of the mule, their stiffened legs sticking out awkwardly from the other side, bobbing up and down as the mule walked.

Then a soldier came out into the cowshed and said there were some more bodies outside. We went out into the road. Four mules stood there, in the moonlight, in the road where the trail came down off the mountain. The soldiers who led them stood there waiting. “This one is Captain Waskow,” one of them said quietly.

Two men unlashed his body from the mule and lifted it off and laid it in the shadow beside the low stone wall. Other men took the other bodies off. Finally there were five lying end to end in a long row, alongside the road. You don’t cover up dead men in the combat zone. They just lie there in the shadows until somebody else comes after them.

The unburdened mules moved off to their olive orchard. The men in the road seemed reluctant to leave. They stood around, and gradually one by one I could sense them moving close to Capt. Waskow’s body. Not so much to look, I think, as to say something in finality to him, and to themselves. I stood close by and I could hear. One soldier came and looked down, and he said out loud, “God damn it.” That’s all he said, and then he walked away. Another one came. He said, “God damnit to hell anyway.” He looked down for a few last moments, and then he turned and left.

Another man came; I think he was an officer. It was hard to tell officers from men in the half light, for all were bearded and grimy dirty. The man looked down into the dead captain’s face, and then he spoke directly to him, as though he were alive. He said: “I’m sorry, old man.”

Then a soldier came and stood beside the officer, and bent over, and he too spoke to his dead captain, not in a whisper but awfully tenderly, and he said:

“I sure am sorry, sir.”

Then the first man squatted down, and he reached down and took the dead hand, and he sat there for a full five minutes, holding the dead hand in his own and looking intently into the dead face, and he never uttered a sound all the time he there.

And finally he put the hand down, and then reached up and gently straightened the points of the captain’s shirt collar, and then he sort of rearranged the tattered edges of his uniform around the wound. And then he got up and walked away down the road in the moonlight, all alone.

The Horrible Waste of WarNormandy Coast, France

I took a walk along the historic coast of Normandy in the country of France.

It was a lovely day for strolling along the seashore. Men were sleeping on the sand, some of them sleeping forever. Men were floating in the water, but they didn’t know they were in the water, for they were dead.

The water was full of squishy little jellyfish about the size of your hand. Millions of them. In the center each of them had a green design exactly like a four-leaf clover. The good-luck emblem. Sure. Hell yes.

I walked for a mile and a half along the water’s edge of our many-miled invasion beach. You wanted to walk slowly, for the detail on the beach was infinite.

The wreckage was vast and startling. The awful waste and destruction of war, even aside from the loss of human life, has always been one of its outstanding features to those who are in it. Anything and everything is expendable. And we did expend on our beachhead in Normandy during those first few hours.

Here in a jumbled row for mile on mile are soldiers’ packs. Here are socks and shoe polish, sewing kits, diaries, Bibles and hand grenades. Here are the latest letters from home, with the address on each one neatly razored out – one of the security precautions enforced before the boys embarked.

Here are toothbrushes and razors, and snapshots of families back home staring up at you from the sand. Here are pocketbooks, metal mirrors, extra trousers, and bloody, abandoned shoes. Here are broken-handled shovels, and portable radios smashed almost beyond recognition, and mine detectors twisted and ruined.

Here are torn pistol belts and canvas water buckets, first-aid kits and jumbled heaps of lifebelts. I picked up a pocked Bible with a soldier’s name in it, and put it in my jacket. I carried it half a mile or so and then put it back down on the beach. I don’t know why I picked it up, or why I put it back down.

An Inhuman TensenessSt. Lo, France

It is possible to become so enthralled by some of the spectacles of war that you are momentarily captivated away from your own danger.

That’s what happened to our little group of soldiers as we stood in a French farmyard, watching the mighty bombing of the German lines just before our breakthrough.

But that benign state didn’t last long. As we watched, there crept into our consciousness a realization that windrows of exploding bombs were easing back toward us, flight by flight, instead of gradually forward, as the plan called for.

Then we were horrified by the suspicion that those machines, high in the sky and completely detached from us, were aiming their bombs at the smokeline on the ground – and a gentle breeze was drifting the smokeline back over us!

An indescribable kind of panic comes over you at such times. We stood tensed in muscle and frozen in intellect, watching each flight approach and pass over us, feeling trapped and completely helpless.

And then all of an instant the universe became filled with a gigantic rattling as of huge, dry seeds in a mammoth dry gourd. I doubt that any of us had ever heard that sound before, but instinct told us what it was. It was bombs by the hundred, hurtling down through the air above us.

We dived. Some got in a dugout. Others made foxholes and ditches and some got behind a garden wall – although which side would be “behind” was anybody’s guess.

I was too late for the dugout. The nearest place was a wagon-shed which formed one end of the stone house. The rattle was right down upon us. I remember hitting the ground flat, all spread out like the cartoons of people flattened by steam rollers, and then squirming like and eel to get under one of the heavy wagons in the shed.

An officer whom I didn’t know was wriggling beside me. We stopped at the same time, simultaneously feeling it was hopeless to move farther. The bombs were already crashing around us.

We lay with our heads slightly up – like two snakes – staring at each other. I know it was in both our minds and in our eyes, asking each other what to do. Neither of us knew. We said nothing.

We just lay sprawled, gaping at each other in a futile appeal, our faces about a foot apart, until it was over.

There is no description of the sound and fury of those bombs except to say it was chaos, and a waiting for darkness. The feeling of the blast was sensational. The air struck you in hundreds of continuing flutters. Your ears drummed and rang. You could feel quick little waves of concussions on your chest and in your eyes.

A French CelebrationParis, France

The streets were lined as by Fourth of July parade crowds at home, only this crowd was almost hysterical. The streets of Paris are very wide, and they were packed on each side. The women were all brightly dressed in white or red blouses and colorful peasant skirts, with flowers in their hair and big flashy earrings. Everybody was throwing flowers, and even serpentine.

As our jeep eased through the crowds, thousands of people crowded up, leaving our narrow corridor, and frantic men, women and children grabbed us and kissed us and shook our hands and beat on our shoulders and slapped our backs and shouted their joy as we passed.

We entered Paris from due south and the Germans were still battling in the heart of the city along the Seine when we arrived, but they were doomed. There was a full French armored division in the city, plus American troops entering constantly.

The farthest we got in our first hour in Paris was near the Senate building, where some Germans were holed up and firing desperately. So we took a hotel room nearby and decided to write while the others fought. By the time you read this I’m sure Paris will once again be free for Frenchmen, and I’ll be out all over town getting my bald head kissed. Of all the days of national joy I’ve ever witnessed this is the biggest.

A Letter from HomeOkinawa, Japan

… Marines may be killers, but they’re also just as sentimental as anybody else.

There is one pleasant boy in our company whom I had talked with but didn’t have any little incident to write about him, so didn’t put his name down. The morning I left the company and was saying goodbye all around, I could sense that he wanted to tell me something, so I hung around until it came out. It was about his daughter.

This Marine was Corp. Robert Kingan of Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio. He had been a Marine for thirteen months and over here eleven months. His daughter was born about six weeks ago. Naturally he has never seen her, but he’s had a letter from her!

It was a V-letter written in a childish scrawl and said: “Hello, Daddy, I am Karen Louise. I was born Feb. 25 at four minutes after nine. I weight five pounds and eight ounces. Your Daughter, Karen.”

And then there was a P.S. on the bottom which said: “Postmaster – Please rush. My Daddy doesn’t know I am here.”

Bob didn’t know whether it was actually his wife or his mother-in-law who wrote the letter. He thinks maybe it was his mother-in-law – Mrs. A. H. Morgan – since it had her return address on it.

So I put that down and then asked Bob what his mother-in-law’s first name was. He looked off into space for a moment, and then started laughing.

“I don’t know what her first name is,” he said. “I always just called her Mrs. Morgan!”