(Earth Eats theme music)

KAYTE YOUNG: From WFIU in Bloomington Indiana, this is Earth Eats. I'm your host Kayte Young.

BOB QUINN: And I saw this old fellow passing out something, and he called me over and he said, "Hey sonny, I said would you like some of King Tut's Wheat?"

And I said "Sure."

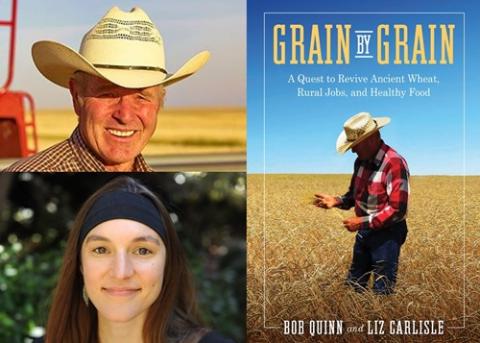

KAYTE YOUNG: On our show this week we're exploring ancient varieties of wheat... in particular, kamut. Eric Schedler of Muddy Fork Bakery shares it why he likes to use it in pizza dough, and we'll hear more about the grain itself from the authors of a book called Grain By Grain; A Quest to Revive Ancient Wheat, Rural Jobs, and Healthy Foods. That's all just ahead, so stay with us.

(upbeat poppy music)

Let's get started with a trip out to Muddy Fork Bakery, located just east of Bloomington Indiana. Eric Schedler is co-owner and master baker at Muddy Fork.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Okay today we are going to make some pizza, and we’ll start with the dough. This is gonna make one pound of dough. So, we'll make like one large pizza, or... what we're gonna do today is make two small pizzas.

And this dough is gonna have a mixture of three kinds of flour, water, a little bit of olive oil and the yeast and salt. So, we’re gonna start by measuring the water and hydrating the yeast.

So, we need 180 grams of water for the yeast. I use very use very little yeast in pizza dough because I use an overnight process, where the dough... we'll let it rise, or ferment today, during the day, and then we'll form our dough balls and let them sit overnight in the fridge. And you don't want them to get super puffy during all that time so we'll use quite a bit less yeast then we would use with any other dough.

(sounds of measuring)

KAYTE YOUNG: And that'll just slow down the process.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Yes, that's right. You want your dough to come out of the fridge the next day very relaxed and easy to stretch, but not so puffed up that it collapses.

We're using about a quarter gram of yeast, which is about a quarter of a quarter teaspoon. Cause we have a standard conversion of a quarter teaspoon to one gram. So, mix that little bit of yeast, and then it's gonna go very slow and long. sound of mixing in a metal bowl)

KAYTE YOUNG: And what is the benefit of the longer fermentation process?

ERIC SCHEDLER: You do get really nice flavors developing when you let your dough go for a whole day. You get more of those organic acid compounds that... we describe that as savory flavors, fermentation flavors. And with the pizza dough it's just so much easier to stretch out the dough after it has relaxed overnight. And we'll get to see that at the end of the show.

So, we've got our water, our yeast, and we're gonna put our 13 grams of olive oil in here.

Bakers describe recipes in terms of percentages, what we call baker's percentages. If you're a mathematician it might... it might irritate you, because it adds up to more than 100%. But the way that bakery recipes work is the flour counts as a 100% and then everything else is relative to the flour by weight.

So, in this case, the olive oil is 5%, 60% is all purpose flour, 20% is whole grain spelt, and 20% is whole grain kamut. So, 155 grams... of the all-purpose, 50 grams of the kamut flour, which is this beautiful golden yellow color. I love working with kamut, it's the most different of the wheats, and can be challenging, especially when you're trying to form loaves that you hope will rise up tall. But it is interesting, and it's got a very mild, almost sweet flavor to it. And here's the spelt which is a more reddish-brown color like whole wheat, and that's gonna give the dough a really nice extensible quality to it. And I'll add the salt, four grams which is a scant teaspoon.

(sounds of mixing dough)

I'm just gonna briefly stir the flours together... and then we're gonna add the flour to the water and oil. And both the kamut and spelt have this quality of coming together more quickly than modern wheats. So, with that 40% ancient grains in there you can see the dough immediately become somewhat cohesive.

KAYTE YOUNG: I'm noticing your primary tools are a nice sturdy wooden spoon and a plastic dough scraper... bowl scraper?

ERIC SCHEDLER: Yeah, bowl scrapers are great. It's also a really good cleaning tool. Anything that's doughy, just get it a little bit wet, and then scrape off the dough.

Okay, so now we're mixing or kneading the dough just a little bit. We’re using this motion of pulling the edge of the bowl, little piece of dough, pushing it down into the middle, and spinning the bowl. And we're just gonna do this for a couple minutes until the dough is all... until the ingredients in the dough are evenly distributed. So, I don't want to see streaks of one kind of flour, or dry, or wet streaks in the dough.

KAYTE YOUNG:That is a pretty sticky dough.

ERIC SCHEDLER: It is, at this point. But it will change as it sits. It will become smoother, it'll become stiffer, as those grains hydrate.

That's mixed enough. Alright, so I'm just gonna scrape down the loose bits of dough from the sides of the bowl down into the main piece of dough and set that aside with a piece of plastic over the top.

(Jazzy poppy music)

KAYTE YOUNG: We left the covered dough alone for a while at room temperature on the kitchen counter.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Alright it's time to come back to our pizza dough. It's been fermenting away in the corner for a few hours. And we wanna make pizza tomorrow, so we prepare the dough today. We let it ferment for 3 hours, good amount of time. And then we're gonna make it into a ball and put the ball in a bag and put that in the fridge overnight. And then tomorrow it will be super easy to stretch out.

One of the interesting things that we do in our bakery, is with any of our doughs that have a good amount of whole wheat in them, or wheat-family grain, we like to shape them with water on the table instead of flour, as the barrier that prevents sticking. So, I’m gonna just do that here.

Turn that dough out. And every time I touch the dough, I dip my hand in a little bowl of water. I'm gonna cut my two eight-ounce pieces for two small pizzas. And then I got the table just a little wet, my fingers are a little wet, and I shape that pizza dough into a nice tight ball. Let it rest on the seam.

(sounds of scraping and folding)

And then before I put them in away in bags, I like to roll them in a rice wheat flour mix. I get them nice and coated in that. They'll still be sticky by the time we take them out, because they can't breathe in there, but it will come off the bag. And that's it. Put them in the fridge to rest until tomorrow.

(sounds of crinkling plastic bag)

KAYTE YOUNG:We'll come back to make the pizza later on in the show. Next up Alex Chambers interviews the authors of Grain by Grain, just ahead, after a quick break.

(Earth Eats production support music)

KAYTE YOUNG: Production support comes from: Elizabeth Ruh, Enrolled Agent, providing customized financial services for individuals, businesses, disabled adults including tax planning, bill paying, and estate services. More at Personal Financial Services dot net

Bill Brown at Griffy Creek Studio, architectural design and consulting for residential, commercial and community projects. Sustainable, energy positive and resilient design for a rapidly changing world. Bill at griffy creek dot studio.And Insurance agent Dan Williamson of Bill Resch Insurance. Offering comprehensive auto, business and home coverage, in affiliation with Pekin Insurance. Beyond the expected. More at 812-336-6838.

Eric Schedler mentioned a couple of ancient grains he mixes in with all-purpose flour for Muddy Fork's pizza dough. To learn more about one of those grains - kamut, we go to producer Alex Chambers.

(minimal spacious music)

ALEX CHAMBERS: The story starts in an American air base in Portugal. It's 1949, and there's a pilot from a farm in Fort Benton Montana.

He's chatting with another American and he says "Hey, check this out. I was just on furlough in Egypt. I got into one of those old tombs... not too far from the pyramids, you know? And I found something... here." And he drops 36 seeds into the pilot's hand.

The pilot grew up on a farm, so he knows his wheat... but the kernels are a lot bigger than he's used to. He mails them to his father back home. His father plants them... 32 of them come up. He replants their seeds, and in a few years, he has bushels. Local mailman gets a hold of some and starts passing them out to all his customers, calling it "King Tut's Wheat".

Bob Quinn was a teenager at this point, growing up on a farm in the 1960's. One day he went to a county fair in Fort Benton.

BOB QUINN: And I saw this old fellow passing out something, and he called me over and he said, "Hey sonny, I said would you like some of King Tut's Wheat?"

And I said "Sure."

Poured this handful of grain in my hands, and it was giant. It was about three times the size of the wheat I was familiar with growing on our farm. And the story was that it came out of a tomb in Egypt, and that was quite a novelty. And everybody kind of wowed over it, but nobody did anything with it, past being a novelty, and I pretty well forgot about it.

ALEX CHAMBERS: Until years later that is, when it would give bob new insights into how modern wheat might be affecting people's health and help him transform the farm economy of north central Montana.

Bob started out as a strong believer in chemical farming. He even got a PhD in plant biochemistry. But then he went back to the family farm and he's been farming organically for 30 years. He served on the first National Organic Standards Board, and among other things he started a company that sells that ancient wheat, which he calls kamut. Maybe you've heard of it. Bob also has a book out called grain by grain that he co-wrote with Liz Carlie.

Liz Carlie: So, I’m Liz Carlie, I am also Montanan. Left the state at 18 but found myself back there visiting with organic farmers, and now teach and write about sustainable agriculture.

ALEX CHAMBERS: Because I bake a lot of bread, the part of the book that I was most interested in was the ancient wheat. But it turned out that kamut can tell us a lot about the wheat we eat today, and how we farm, and even about jobs, rural economies, and multinational corporations.

But first I wanna get back to the story of that strange ancient wheat. After the county fair Bob forgot about it for years. Then one day, in grad school...

BOB QUINN: I was eating a package of Corn Nuts, kind of just idly in the hall one afternoon, taking a little break. And on the back of the package it said, "Corn Nuts: Made with a Giant Corn". and I thought "What if Corn Nuts would be interested in a giant wheat?"

So, I called them up, they were in nearby Oakland, and they said "Yeah, we might be interested in that."

And I called my dad right away, and I said, "Dad see if you can find some of that old King Tut's Wheat." And in a week or so he said he found the jar in a friend of his basement, and we sent a couple tablespoons to Corn Nuts, and they loved it. And they said "Wow, we'll 10,000 pounds of this stuff, this is fantastic" and I said "Well... I don't really have 10,000 pounds." I didn't want to tell them, I didn't even have one pound.

ALEX CHAMBERS: So, he called his dad and said, "Plant it all." They planted two crops a year for two years and got up to 50 pounds. He called Corn Nuts again, but the guy he'd talk to was gone, and no one was interested.

BOB QUINN: And so, we just put it in the shed. And there it sat until about 86' when we went to our first health foods show in California-

ALEX CHAMBERS: Where, out of the hundreds of people who walked by, only one showed any interest. But that one conversation lead to a contract.

BOB QUINN: From that we planted the whole 50 pounds on half an acre, and 30 years later we're up to 250 farmers all over Montana,13:50(unable to make out what he's saying), all organic, planting over 100,000 acres. So that's how it blossomed, and I had no idea it would do anything like that.

ALEX CHAMBERS: But Bob still didn’t really know where the grain came from. He knew it couldn't be from a 4,000-year-old tomb because it wouldn't have grown. So, what was this wheat?

It got clearer after he started shipping to Europe. At a food show there...

BOB QUINN: I ran into a fellow from Egypt and he invited me to Egypt.

ALEX CHAMBERS: So, he went to the Cairo museum and took a look at the ancient wheat kernels that had been found in the tombs. It didn't look anything like his wheat.

BOB QUINN: And so, I was pretty dejected, because we've been telling this story for 10 years or so.

ALEX CHAMBERS: But he kept trying to figure it out. He took a trip to Turkey and people recognized it here. They told him they call it Camel Tooth because the kernel has a kind of hump on it. They also said they call it the Prophet's Wheat.

BOB QUINN: And I asked them - why do they call it the Prophet's Wheat? And they said... I said, "Does this have something to do with Mohammed?"

And they said "Oh no, no, not that prophet. You know the one with the boat."

I asked them, I said: "Well, you mean Noah?" and they said, "Oh yes, it's the grain Noah brought with him on the ark."

And I said "Wow, that's a lot better than my old tomb story."

ALEX CHAMBERS: Although you know the tomb story is pretty good. In any case, after more sleuthing he eventually figured out it was most likely a variety from the Khorasan region of Iran.

He trademarked it as Kamut - an ancient Egyptian term for wheat. The trademark meant that any farmer who used that name had to grow it organically. As the grain became more popular, people who usually had problems eating wheat, realized they could eat kamut breads and pastas without their usual symptoms.

BOB QUINN: And I was very curious to try to figure out why that was so, what was different, and what we had changed. And we had a hard time finding researchers in America that was interest... took seriously that this claim. Most of the said "Oh, this is just all in their head. People say they can eat one thing or can't eat another." But in Italy we found that a very great interest in this question.

ALEX CHAMBERS: So, they teamed up with researchers in Italy to see how rats were affected by diets of ancient versus modern wheat, and what they found surprised them. The rats eating modern wheat had a lot of inflammation, whereas the ones in ancient wheat had none. That was a big deal, because inflammation is a factor in a lot of chronic disease. Then they did clinical trials with human volunteers and had similar results.

And it wasn't just inflammation. The groups eating ancient wheat had much lower cholesterol than the ones with modern wheat. Even the people who were on medication.

BOB QUINN: So, it was really an astonishing discovery. And it was so consistent, that every single person had similar responses that it really gave us a brand new picture of what we had done to modern wheat in its breeding program that changed the gluten, and changed the yield potential, and everything that we'd been doing.

ALEX CHAMBERS: And if that's the case... if ancient wheat really is better for us, Liz Carlisle thinks we should listen to that.

LIZ CARLISLE: Wheat is trying to tell us something. You know... this grain that we've had a longstanding relationship within human society is one of the first crops really that we developed in the way that we understand the crop. It's trying to tell us something about what's wrong with the food system.

ALEX CHAMBERS: From raising food with so many chemicals, to taking out the nutrients, and processing, even how we breed our crops.

LIZ CARLISLE: A lot of the food we eat comes from a very small number of crops. And that small number of crops are the ones that have been breed really intensively for just a couple of goals - high yield, and in the case of wheat, high loaf volume. But along the way, people weren't really paying attention to things like nutrition.

ALEX CHAMBERS: And not just our bodily health, but the health of our land and local economies. Liz says in industrial agriculture most of the money doesn't go to the farmer, it goes elsewhere in the supply chain, like the fertilizer and pesticide and seed companies, and expensive machinery. At the other end of the food chain it goes to the processor.

LIZ CARLISLE: So as a result you have these areas of the U.S.; you're in one yourself, where there's a lot of agriculture, but not very much money is actually staying in that community with the farmers or with the small businesses that farmers would support. Whereas with organic agriculture, essentially what I see, is that instead of the money going to chemicals, the money is going to people.

ALEX CHAMBERS: So why isn't everyone switching to organic?

Bob Quinn says its partly because for so many farmers, converting to organic is a step into the unknown. It's a big risk and there's very little support from the USDA. But there are cultural pressures too. Major multinational corporations make a lot of money off of the current system, and they don't have any real incentive to change.

LIZ CARLISLE: And also, I think... you know, in more nuanced ways, in communities they've been very sophisticated about getting their messaging out in rural American, but also in you know urban America where people eat. And convincing people that they really have the best interest in the farm community and the American public at heart.

ALEX CHAMBERS: Liz has seen some of the major ways that major ad corporations have deliberately created a cultural divide. At farm conventions and in rural advertising, they tell farmers that organic agriculture...

LIZ CARLISLE: Is a project of urban environmentalists and foodies who don't understand what's happening in farm country, to insult and discount and disrespect the hardworking family farmer. And so, this messaging goes... it's really the chemical companies that have the farmers' interests at heart, understand what they're going through on a daily basis, and are gonna provide them the tools they need to deal with their problems.

ALEX CHAMBERS: Still, Bob and Liz are both optimistic. Bob's had more calls in the last 18 months from farms wanting to convert to organic than in the last 30 years. And Liz says that addressing the issues in our food system is helping us achieve human potential.

LIZ CARLISLE: And really becoming what we're capable of in terms of the way we can care for each other, and live in community, and also steward and care for the rest of the planet.

ALEX CHAMBERS: You can learn more about kamut wheat and its role in the health of soil and local communities, and some of the new research on ancient versus modern wheat and how it affects our bodies, in Bob Quinn’s and Liz Carlie’s book, Grain by Grain, A Quest to Revive Ancient Wheat, Rural Jobs, and Healthy Food. It was pretty fascinating. We've got a link on our website.

(minimal spacious music)

KAYTE YOUNG: That story comes to us from producer Alex Chambers.

(Jazzy, poppy upbeat music)

At Muddy Fork they bake their bread in a large wood-fired brick oven. It gets fired up once a week and holds heat for days. On the day I visited the oven was too cool for pizza, so we headed up the driveway to Eric's house to finish the pizzas.

On the walk up we talked about sourcing local cheese.

(sound of footsteps on gravel)

ERIC SCHEDLER: It's called Ludwig Farmstead, it's a place in Fithian Illinois which is not that far from Indianapolis. We met those people at the Indy Winter Market. And they make some really go hard cheeses that you can get around town at Bloomingfoods and they also make a really great fresh mozzarella that we get from them all summer long for our market pizzas.

KAYTE YOUNG: Nice.

ERIC SCHEDLER: It just has this great curd to it. It's so firm and stretchy and when it melts it's got the perfect texture.

KAYTE YOUNG: Eric's wife Katie and their youngest daughter Ruthie had just gotten home. You might hear Ruthie in the background.

(Sound of door squeaking and opening, interior sounds)

ERIC SCHEDLER: Alright, so we're gonna make some pizza sauce to put on those pizzas. And this is how we do it for market. It's mostly just tomatoes, and at this time of year go for canned, whole, organic tomatoes. So, we have a quart of tomatoes going in the food processor, include the juice.

And then we'll put in half a teaspoon of salt, and a half a teaspoon of honey, and herbs and half a tablespoon of olive oil, and right now I have some frozen... I call it pre-pesto. I harvested lots and lots of basil in summer and processed it just with olive oil. So that's gonna be my olive oil and my herbs. So, I'm gonna put -

KAYTE YOUNG: And then you froze it?

ERIC SCHEDLER: I froze it, yes. But I'm just gonna put a nice scoop of that in there.

There you go. It smells like pesto with all that basil oil. So, one of my favorite things to put on pizza is kale and garlic. And you just take kale and strip the leaves off of the stems. And toss it in a generous amount of olive oil and salt. And put it right over the top of your pizza, as thick as you can get away with.

(sound of ripping kale)

And I'm gonna pour over some olive oil and sprinkle some salt on it. It's a little messy but the best way is to massage it in, and kale kind of wilts from the salt and the oil. And I can just eat a bowl of it just like this.

(sound of salt hitting kale)

Looks good. Okay, I'm gonna chop some garlic. We're gonna throw it on with the kale that we prepared onto this pizza.

(chopping sounds)

Okay, so I'm taking this pizza dough out of the fridge and out of the bag and I'm just gonna dump it into our little container of rice flour and get both sides of it nice and coated. And I've already put some rice flour onto the peel. And I'm gonna stretch this out right here on the peel. And I'm just using gravity a little bit to stretch out the dough, holding it from different angles, and draping it over my hands. It's a very gentle process of tugging and when you let your dough relax overnight it really just stretches itself. It's hardly any work.

And there we go, I'm gonna stick it on a peel. This is a half-pound of dough, so it makes a little medium-small pizza. And we have... start with some of that sauce that we made. Put a couple spoonfuls of that on the pizza, spread it around.

KAYTE YOUNG: I notice you're going kind of light on the sauce.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Yeah. I don't like to put too much of anything on a pizza, because you don't want to make your pizza too heavy. Next is cheese, and I told you about the Ludwig Farmstead Mozzarella that we love using. So, we're gonna rip up a little bit of that and put it on the pizza.

KAYTE YOUNG: You can also just use grated cheese...?

ERIC SCHEDLER: Yes. It's traditional to rip it up, but actually for... and we're making... you know, 20, 25 pizzas at a farmer's market, we just grate it ahead of time because it reduces the work on site. And then we've got our kale and I really do mound up the kale because it disappears as it cooks. It shrinks a lot.

KAYTE YOUNG: And it's so light, it's not gonna weigh down the pizza.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Right. And then put that garlic over the top, more or less, depending how much you like garlic. And in we go into a hot oven. On your pizza stone or leftover fire bricks.

(scraping sound)

KAYTE YOUNG: You want to get your ovens as hot as it goes. For most of us that’s 500 degrees Fahrenheit, but some ovens do get higher. Using a preheated pizza stone helps hold the heat and can give your pizza a crispy bottom crust.

(jazzy, poppy upbeat music)

Eric had some leftover fire bricks from when they built the bakery oven. He put those in his home oven for baking pizza or pita bread. The pizzas will bake for about 10 minutes, just keep an eye on them, look for a browning crust, and bubbling cheese.

KAYTE YOUNG: Now we gotta try this pizza. Mm... god is that kale is so amazing.

ERIC SCHEDLER: Sweet winter kale.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yeah, the crust has so much flavor and its really crunchy on the outside, and then where all the cheese and the kale and everything is its soft. Oh, it's just delicious. Thank you so much Eric.

ERIC SCHEDLER: You're welcome.

KAYTE YOUNG: You might have to wait until winter to sample some of Muddy Fork's pizza, but you can find them with bread, pastries and granola at the Bloomington Winter Farmers' Market every Saturday throughout the winter. The market has a new location at the Switchyard Park Pavilion on South Rogers. Find more information and the recipe for Muddy Fork's Pizza Dough at EarthEats.org.

If you like what you heard today, tell a friend, subscribe to our podcast, or leave us a review on iTunes. It helps others find us. Thanks for listening.

(Earth Eats theme music)

Renee Reed: The Earth Eats team includes Eobon Binder, Chad Bouchard, Mark Chilla, Abraham Hill, Taylor Killough, Josephine McRobbie, Daniel Orr, The IU Food Institute, Harvest Public Media and me, Renee Reed. Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Earth Eats is produced and edited by Kayte Young and our executive producer is John Bailey.

KAYTE YOUNG: Special thanks this week to Alex Chambers, Bob Quinn, Liz Carlisle, Eric Schedler, and everyone at Muddy Fork Bakery.

Production support comes from: Insurance agent Dan Williamson of Bill Resch Insurance. Offering comprehensive auto, business and home coverage, in affiliation with Pekin Insurance. Beyond the expected. More at 812-336-6838. Elizabeth Ruh, Enrolled Agent with Personal Financial Services. Assisting businesses and individuals with tax preparation and planning for over fifteen years. More at Personal Financial Services dot net. And Bill Brown at Griffy Creek Studio, architectural design and consulting for residential, commercial and community projects. Sustainable, energy positive and resilient design for a rapidly changing world. Bill at griffy creek dot studio.