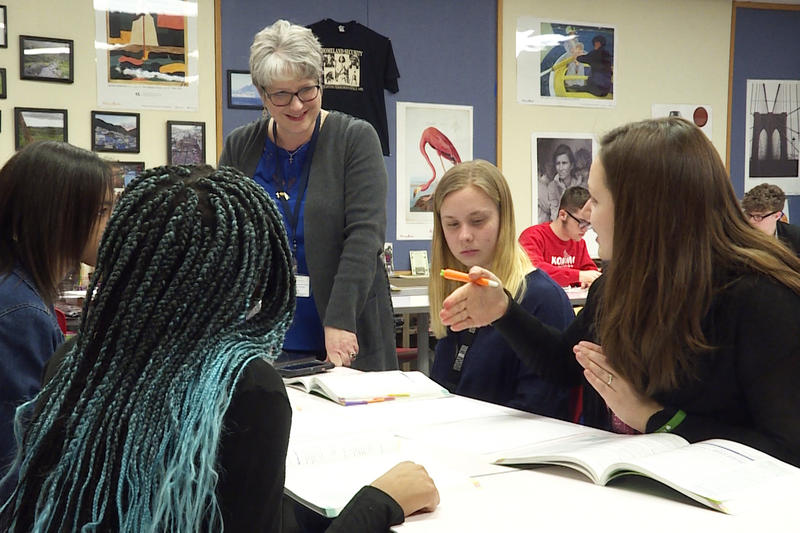

Becky Stoltzfus has been a teacher for 24 years, and says she’s worried about the future of teaching in the state. (Zach Herndon/WTIU)

Widespread protests in several states have brought teacher pay and school funding into the spotlight, and this year, Indiana educators have pressed for statewide action on the same issues.

Many lawmakers say they’re doing what they can and feel confident their proposals start to address teacher compensation, but many Hoosiers in classrooms and schools don’t share that same optimism and say they need to see more from the state after years of inadequate funding.

Becky Stoltzfus has known since she was in eighth grade that she wanted to teach, and she’s followed her dream teaching for more than 20 years in Kokomo. It’s her passion, but with limited benefits and pay she’s questioning whether she needs to start looking into other career options.

“And it breaks my heart that I might actually have to do something different,” she says.

Stoltzfus teaches five subjects, has a master’s degree, and a Ph.D.’s worth of college credits. She usually applies for free trips in the summers to travel the world and bring back pieces of history for her students, but this year she’s planning to put those trips on hold.

“I’m going to be looking for a second job,” she says. “I’m either hoping to substitute teach here at the school, or I have friends who work at J.C. Penney.”

Stoltzfus is at the top of her school’s pay scale and has limited options to boost her pay; she recently cut back on her insurance coverage to earn more.

Teachers say to fix the state’s ongoing shortage and “teacher crisis,” a few things need to change, starting with compensation they say is lacking because of poor school funding.

According to the National Education Association, Indiana’s average full time teacher pay lands at $50,218. That varies wildly from district to district, but teacher wages in neighboring states have only added to the pressure in Indiana.

A report from Teach Plus and Stand For Children Indiana says the state ranks last behind Kentucky, Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois for average teacher pay, and needs to spend at least another $650 million each year to be competitive in the region.

But lawmakers, including one of the state’s lead budget writers Rep. Todd Huston (R-Fishers), say they have a plan to start moving more dollars to teachers.

“We’re leveraging a $150 million investment to save local schools $70 million a year,” Huston says.

That investment is a proposal Gov. Eric Holcomb announced in January, to use part of the state’s surplus and pay off some teacher pension debt for schools. The idea is hopefully, schools that see those savings will use the money to pay their teachers more.

Some districts won’t save as much as others from the pension pay off, and lawmakers have so far refused to require schools pass on those savings to teachers.

But that’s why Huston says House Bill 1003 is crucial this year too. It would publicize how schools manage their money, and require the state to collect Indiana-focused teacher pay and school spending data.

“What House Bill 1003 is: let’s make it more transparent,” Huston says. “Let’s make sure communities understand where their dollars are being spent.”

District leaders argue they’ve been working for years to cut costs and streamline expenses, and that it’s already in their best interest to pay teachers as much as they can to fill empty teaching positions in a scarce market.

Kokomo School Corporation Superintendent Jeff Hauswald says his corporation even made changes to its health insurance plan to save the district money and boost teachers' pay, but it created a ripple effect.

“Some of that has come with sacrifices though, right? We’ve had to create a plan that has higher deductibles, so there’s an example” he says. “In 2010 we went through a process and we closed three schools.”

Hauswald is among school leaders who say they’re in a position now where there’s nothing left to cut and the only option is more funding from lawmakers. He says revenue from the state hasn’t been keeping up with inflation, and has resulted in a “fiscal crisis” for public education.

But Huston is advocating for local communities to step up, and says schools can’t rely on lawmakers to do everything.

“You know if you want to pay your teachers a bunch of money and you want to have small classes and you want to have very small schools,” Huston says. “at the end of the day, you’re probably going to have to add a local contribution to that.”

More schools have been looking to local voter-approved referendum options for those kinds of contributions, and about a third of Indiana’s schools have tried.

Some districts can count on their community to pass those regularly, but executive director for the Association of School Business Officials Denny Costerison says others aren’t as lucky.

“We have other districts we know that probably would maybe never be able to get through a referendum,” he says. “For whatever reasons – mostly economic reasons in their communities.”

Costerison says at this point, the state likely needs another revenue source to help fund public schools, or there need to be fewer schools. Costerison says struggling districts may have to consider another hotly debated option: consolidation.

“That’s just the only other option I think they have is to look that way,” he says.

But that’s a complicated process many want to avoid.

Ultimately, teachers like Stoltzfus see low pay as one of several symptoms of a devalued field, and the subsequently lacking pipeline of new teachers has only added pressure to those still in their classrooms.

Many blame a series of changes to the state’s funding formula for leaving a lot of public schools scrambling to come up with cash. They say they want to see a cultural shift toward more respect with better pay – they’re professionals with a job to do.

So will Stoltzfus live out her dream of retiring as a teacher?

“I don’t know,” she says, “and I hate the fact that I’ve actually started to question that.”

Many other Hoosier educators face the same question: should they stay? Right now, their answers depend on how lawmakers respond to their calls for more money.