Two Hoosiers fight the flu in a photo from the 1919 IU Arbutus. (Monroe County Public Library)

Perry Township Trustee Dan Combs is a former history teacher, has a master’s degree in teaching history from IU and was an adjunct professor at Ivy Tech Community College.

Part of Combs’ master’s thesis explained how Monroe County dealt with the 1918 “Spanish Flu” pandemic.

From five years of county death records that corresponded with the pandemic, Combs compiled an extensive dataset of Monroe County deaths caused by the 1918 flu. After combing through scores of newspaper articles from the time, he ended up with an in-depth account of the county’s response to the 1918 pandemic.

Reporter Mitch Legan talked with Combs about what he found out.

Ganstine’s Arrival: Monroe County “Gets” the Flu

Nobody knows for sure how the “Spanish Flu” arrived in Monroe County. Not even Dan Combs.

“I want to say the railroad,” he says. “Just like COVID-19 got around the world by airlines.”

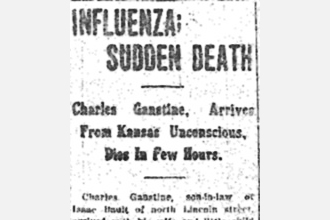

What is known for sure is University of Kansas professor Charles Ganstine was the first person to die from the flu in Bloomington, almost immediately after he got off the train.

“He walked up to the square and went into a drugstore – he got that far,” Combs says. “And then in there, he collapsed. They put him in a wagon and hauled him to that ‘house of pestilence.’”

Ganstine died the next morning, Oct. 7. That same day, Monroe County took action.

“That day (the lockdown) order came out for Bloomington, the newspaper covered it (the flu) like it was fresh news,” Combs says. “And then when you turned in three or four pages was a little article, ‘Flu Present in Bloomington.’ And it said not more than 150 to 200 cases, which meant it'd been stewing around for a month, and not a word. And I mean, I read every word of those newspapers.”

Lockdown 1918

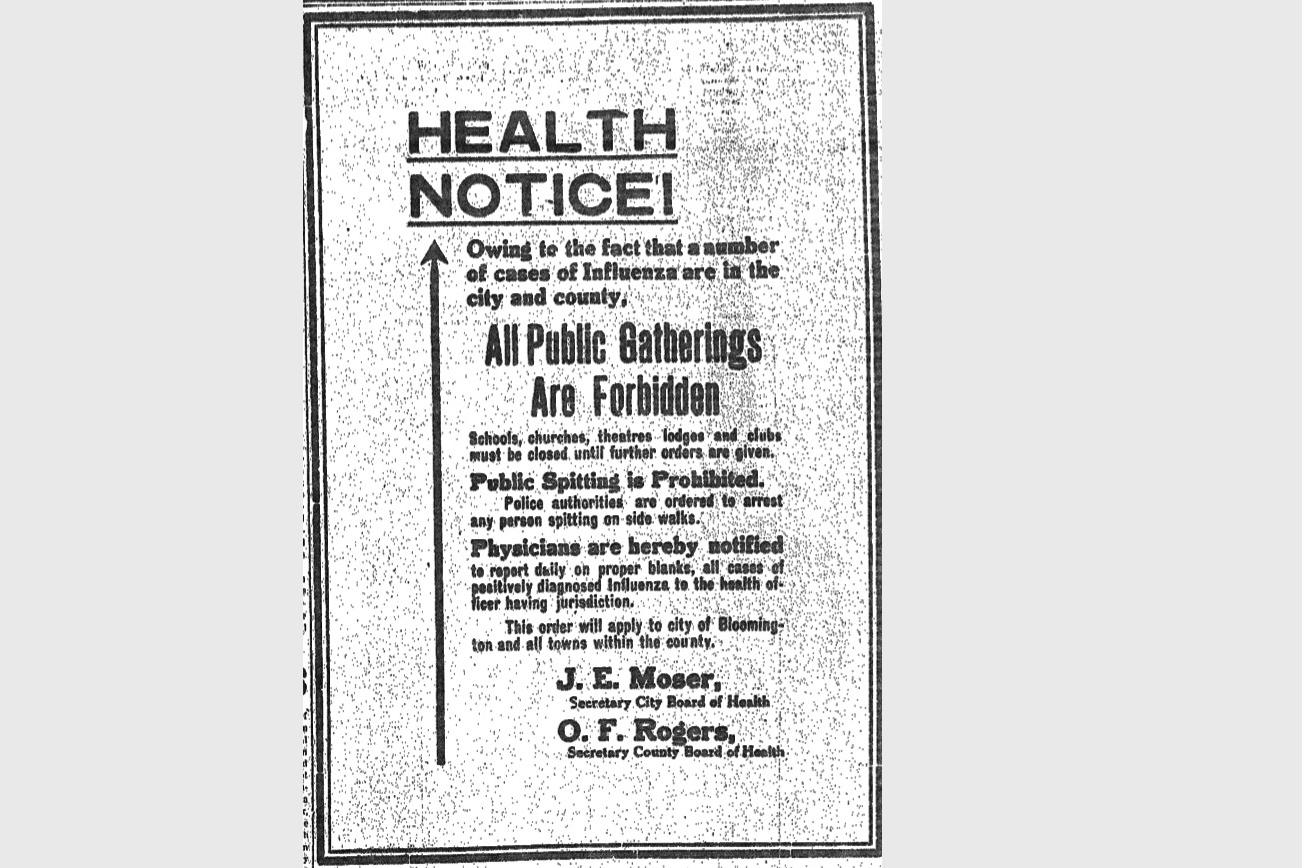

Dr. John Hurty and the State Board of Health declared the lockdown Oct. 7 and Monroe County’s health agencies approved it.

The state orders were already in the works, and numbers show at least one flu death in Monroe County before Ganstine arrived in Bloomington.

The city had previously banned burning “leaves and rubbish” to keep flu-contaminated fumes from the air. Pool halls were ordered closed and spitting in public was criminalized.

Schools, churches, theaters and other gathering places were eventually ordered closed, while large congregations like funerals were also put on hold. Political campaigning was to take place via newspaper advertisements.

Despite all these precautions, factories remained open as part of the war effort.

“The Showers Brothers factory had 1,000 employees there, and they closed in late October through the first half of November because so many employees were sick,” Combs says. “It wasn't, ‘We're closing to keep you all healthy. It's, ‘We just can't run our lines.’”

Indiana University closed three days after Dr. Hurty’s order.

“By (then), the state politicians had convinced (IU President William Lowe Bryan) closing was in good stead,” Combs says. “So IU closed Oct. 10 and they put out a warning letter essentially saying ‘everybody leave town.’ IU was essentially a military base to Student Athletic Training Corps, SATC, and everybody who's not in the SATC must leave town.”

IU locked down from Oct. 10 to Nov. 4.

Reopening 1918: Business, Basketball Reign Supreme?

While IU reopened in early November, Bloomington stayed locked down through December. As the lockdown continued, Hoosiers became increasingly restless and confused by competing orders and extensions coming from the city and county health boards.

With the lockdown intact and cases rising nonetheless, Dr. Hurty gave Bloomington officials the green light to lift restrictions on Dec. 28, 1918, and focus on quarantining those infected instead.

“He wrote a letter to (city health officer) Dr. Luzadder here in Bloomington and told him, ‘I was wrong. The lockdowns were wrong. New York worked, everywhere else failed,’” Combs says. “And when (Hurty) shifted, it was an instant open-up.”

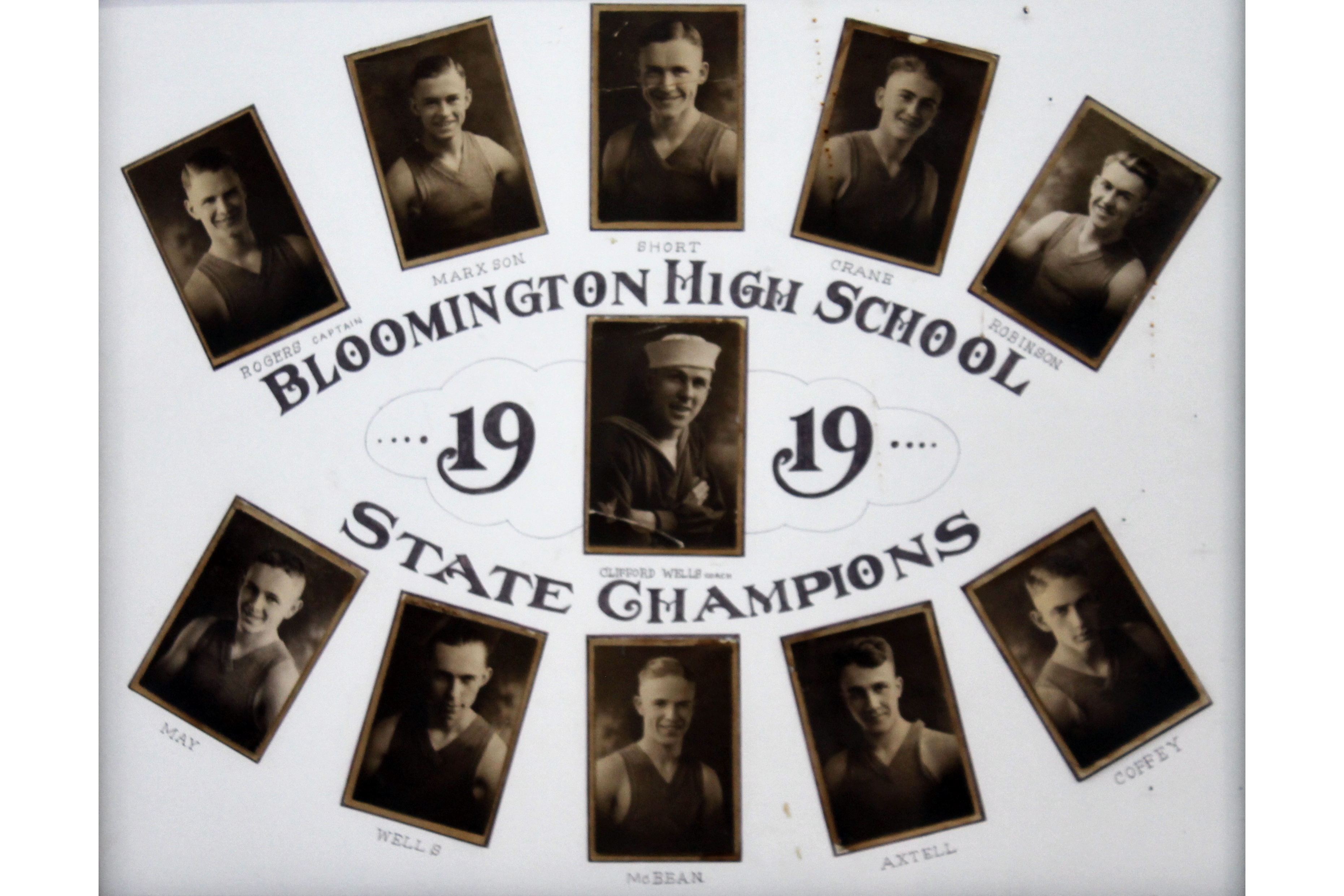

One thing that hadn’t stopped during the lockdown was the Bloomington High School basketball team.

Games began in December but health orders prohibited fans from watching.

“So the men would gather outside the front of the building, and the manager of the team would run back and forth and give them the updates as time went on,” Combs says.

Bloomington went on to be state champions, beating Lafayette 18-15 for the title in March 1919.

The same day of the championship, Bloomington’s newspapers announced the last flu death in Monroe County.

“You can't write an ending like that,” Combs says. “What a way to bring the community out – and they had a parade when (the basketball team) came back to Bloomington.”

Monroe County Flu Numbers: A Second Wave?

Monroe County hadn’t seen the worst of the epidemic yet, although it dropped from the news.

“The local newspapers rarely mention the flu,” Combs wrote in his 2011 thesis. “There are several notations of deaths by ‘pneumonia’ but except for pointing out the flu was occurring in neighboring communities it is almost as if the return of the flu never took place even though the numbers of people reported killed in February, 1920, exceed the numbers killed in October of 1918.”

October 1918 was the deadliest month for the “Spanish Flu” throughout the U.S., but not in Monroe County.

It was the second-deadliest month with 25 deaths. Cases dropped to 19 in November but increased to 24 in December.

Monroe County didn’t see a huge second wave in 1919. But the flu returned in 1920 with a vengeance – February 1920 was Monroe’s deadliest month with 34 flu-related deaths.

Combs’ data counts at least 217 deaths in Monroe County because of the “Spanish Flu.”

“There were parts of the county that were so remote that people might die in December and they can't get to town until March or April to tell the coroner someone had died,” he says. “So you get these self-reporting causes of death that may or may not relate to the actual influenza epidemic.”

When newspapers reported on the flu, they focused on the city’s higher-ups – university folk like Charles Ganstine – and tried to downplay its effects on the city while pointing out neighboring communities’ cases. Diseases like influenza were seen as ailments synonymous with lower-class laborers. One newspaper story denied black people could get the flu, so they also couldn’t die from it.

“If people understood how many died in that event, there would be a monument on the courthouse square,” Combs says. “If an airliner crashed in Monroe County, we would have a living memory of it in 100 years. There's just no living memory – this was squished out.”

For Combs, it’s a story that now, more than ever, needs to be told.

For the latest news and resources about COVID-19, bookmark our Coronavirus In Indiana page here.