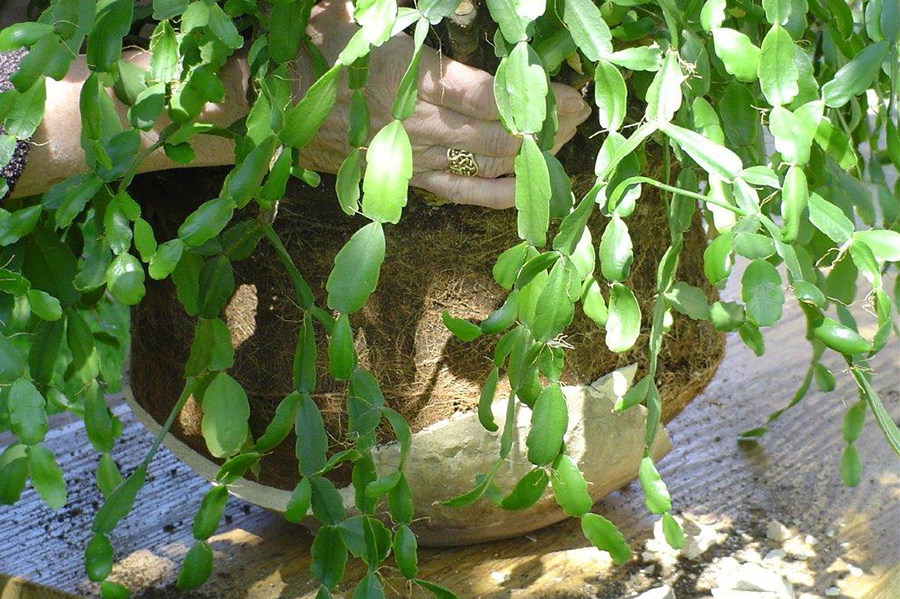

There’s a photograph in the Wylie House – the former residence of Andrew Wylie, Indiana University’s first president – of Rebecca Wylie, the home’s second owner. It’s a simple photo: Rebecca, around 100 years old at the time, sits in her rocking chair, next to the fireplace in the dining room. But just behind her is one of her favorite possessions, a Christmas cactus.

That photograph was taken in 1913. But the cactus is still in the Wylie House, still blooming after well over a century.

Sherry Wise is the outdoor interpreter at the Wylie House Museum. She’s been with the museum for about 19 years, cultivating the house’s garden.

While Wise can’t be sure, she believes the Christmas cactus was about 10 or 15 years old in the photo, putting it around 120 years old at most today.

“It’s a much-loved plant. People just light up when they know this is over 100 years old,” she said.

The Christmas cactus is a member of the Schlumbergera genus, which are native to humid jungles in Brazil. It gets its name from the blooms it produces each year in late autumn and early winter, due to colder weather and less available sunlight.

When asked if she felt pressured to keep a century-old plant alive, Wise shook her head.

“It thrives on neglect,” Wise said. “The easiest way to kill one is to over-water it.”

Christmas cacti have a small root system and thrive in light, aerated soil, so they only need to be watered about once a week. And apart from the occasional re-potting, there’s no exact science for caring for the Wylie House’s cactus. Her only rule is, “Don’t let another staffer take over.”

“One time, I went on a vacation and I let another of the staff members take care of it. It was a mistake, because it had been over-watered. I didn’t water it for probably a month after that. Now, I don’t delegate anymore; it’s better off to just let it be,” Wise said.

The cactus is old, but it happens to be well-traveled as well. When Rebecca Wylie died, the plant was handed down from generation to generation. It eventually landed with Morton Bradley, Rebecca’s great-great-grandson, who lived in the Boston area. Wise said that Bradley had a large collection of IU history in his home; and when he died in the early 2000s, he left his collection to the university. Decades after it left the Wylie House, the cactus returned home.

“If you have a Christmas cactus, you should remember to put it in your will,” Wise said.

Though the cactus is one of the museum’s most unique features, it’s just a small part of the work Wise does as the house’s outdoor interpreter.

“We grow the same kinds of plants that the Wylies would’ve grown when they lived here,” Wise said. “Andrew Wylie…was a farmer by necessity. This was a really small town. This [house] was 25 acres, and he basically grew most of the food to feed his family of 12 children.”

Wise grows a number of fruits, vegetables, herbs and beans in the garden. All the plants grown are heirlooms, meaning that they have not been hybridized with other plant species. And each of the plants have been around for at least 50 years, passed down for generations.

According to Fast Company, 93 percent of unique seed strands went extinct between 1903 and 1983. So, to Wise, keeping these heirlooms growing is as much a conservation effort as it is an historical one. And apart from a few exceptions, none of the produce grown is eaten. Each fruit and vegetable is saved so its seeds can be used to grow the next crop.

All of the work that Wise and the Wylie House staff put into growing its plants results in what she considers a window into how the family lived over a century-and-a-half ago.

With the care taken in preserving these plants, Wise doesn’t see a reason why the Christmas cactus couldn’t make it to 200 years.

Those who want to see the Christmas cactus in full bloom can stop by Wylie House by Candlelight, the museum’s annual open house, on December 14. The staff will be decked out in period attire, and the event will feature era-appropriate decorations and entertainment. More info is available on the Wylie House website.