There are two museums that tend to fly under the radar here in Bloomington. Both are historical residences that provide a peek into the life of a 19th century Hoosier.

The Farmer House Museum, despite its title, is no farm house. The two story brick building was built in 1869 by Rev. Ambrose Moore. He came to town to serve as pastor at the Walnut Presbyterian Church but left just five years later.

Mary Rawles was a widow in Bloomington and looked to make an income. She bought the residence to run it as a boarding house while her family lived on the small lot next door. Her son, William Rawles, eventually became the first dean of the Indiana University Business School in 1920.

“Besides the possible brief time that the Rawles children lived here, there have been no known child tenants,” Museum Director Emily Purcell explained. “It’s never been mom, dad, and two kids here, ever.”

As the house was passed down through the Rawles family, relatives kept the tradition of living in one part of the house while renting out the other. The house became host to an array of different uses.

The spacious downstairs was divided and converted into businesses. In the 1930s, the gallery entrance featured a stationery shop while a barber shop ran out of the back.

The life of the house wasn’t documented in scrupulous detail until its new owners, Indiana natives Ed and Mary Ellen Farmer, took up residence in 1952.

Mary Ellen loved history. After witnessing the destruction of her childhood school and seeing a number of changes in Bloomington, she became adamant in her passion of preserving the past. She successfully stopped the demolition of the Carnegie Library building.

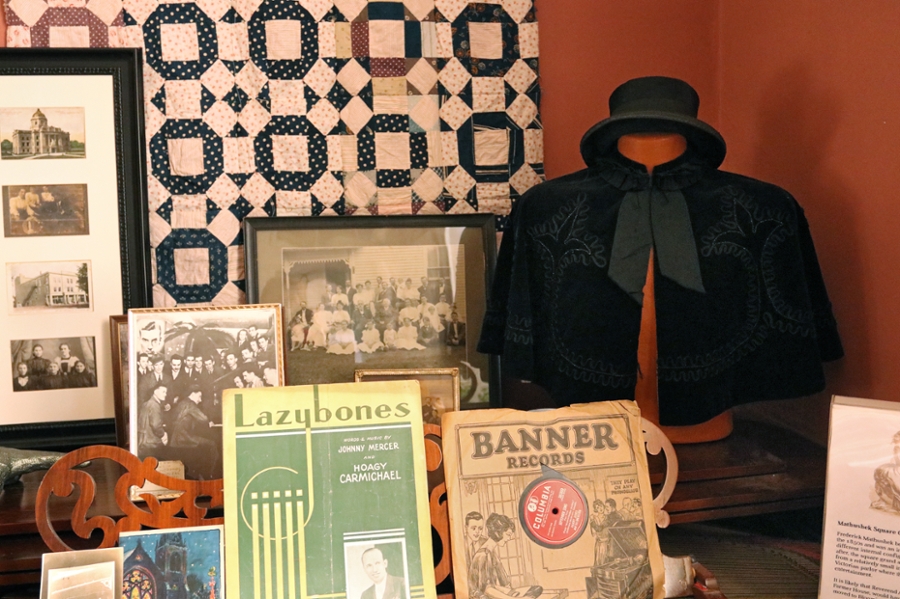

She and her husband, Ed, spent their last years in what became known as “The Farmer House.” Mary Ellen had collected and saved items spanning her entire life that still fill each corner of the house. Some household items belonging to Mary Ellen’s parents date back to the early 1800s.

“The first thing visitors ask is if it’s original to the house, and the short answer is nearly always no,” Purcell said. “The house has been used by a large variety of people for a large variety of purposes.”

While most of the artifacts displayed are from Mary Ellen’s collection herself, some have been added over time.

However, there is one item Emily believes might have been in the house before the Farmers’ time: An old clock that sits silently nestled in the gallery is a perfect reflection of time stood still.

Mary Ellen Farmer passed away in 1999, but her connection with the past has allowed her to live on today through her carefully saved memorabilia.

The Museum is located at 529 N. College Ave. and is open for guided tours Tuesday through Sunday, 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.. Admission is free.

From Farmer House to farmhouse, the Hinkle-Garton Farmstead is a 19th century historical site made up of 11 acres of land. This home has been uniquely historial by housing three generations of Hinkle and Garton families.

John Henry Hinkle and his wife, Laura Ann Rawlins, first settled on their farm in 1886. John was a farmer by trade and built a temporary log cabin for his wife and only child until the construction of his Queen Anne-style farmhouse was complete in 1892.

Originally, the old farmhouse sat in the center of a much bigger plot of land, around 80 acres, and stood surrounded by multiple outbuildings necessary for that time period.

By 1910, a second house was added to the property to accommodate their then grown son, Henry, and his new wife, Bertha Elizabeth Rogers.

Henry was such an avid potato farmer that he became well known as the “Potato King of Monroe County.” He was also famous for his flowers; he started a business out of the farm called “Hinkle’s Dahlia Gardens.”

Henry and Bertha went on to have two children in that second farmhouse - John Henry Hinkle and his sister, Daisy.

Daisy Hinkle became Daisy Garton after marrying Joseph Garton, a music performer and teacher. The two met while studying at IU. She earned her degree in music composition and the two returned to her previous farm life in 1943. She continued her days teaching music to the children of Bloomington.

The land itself became an incredible historical resource. Sprinkled with old farming artifacts, the dirt uncovered the practices and materials that exemplified over three generations of life on the farm.

Old barns and flower gardens span the property and bring color to the old white farmhouse - a farmhouse that has needed quite a bit of TLC over the years.

In 2007, the farmstead was placed on the National Register of Historic Places and continues to be maintained today through Bloomington Restorations, Inc. Deemed Bloomington's most intact farmhouse, the site plays host to seasonal activities and events.

Tap the trees during the Maple Syrup production in the winter, stock up on flowers during the annual plant sale in April, or volunteer to help man the gardens - there is always work to be done on the farm.

Located at 2920 E. 10th St, the farmstead is open to the public every last Saturday of the month from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m.. Admission is free.