Since his teenage years at the end of the ‘60s, Gene Coyle had always wanted to be a diplomat. He even completed an internship with the State Department during his time as a student at Indiana University.

“By the end of that summer, I was bored to tears,” Coyle said.

A mentor he connected with during his time at the State Department, however, suggested that he join the CIA. Coyle took the advice to heart, but was rejected from the agency twice.

After completing a Master’s degree in Eastern European Studies and spending a year in Hamburg, Germany, Coyle decided to apply again. This time, he landed a job. At the age of 24, Coyle said, he was the youngest in his class of trainees at the agency.

Coyle joined the CIA in 1976, when the United States was in the midst of the Cold War. In the ‘80s, Coyle spent time in Moscow working under the nose of the KGB. He said that getting assigned to the Soviet Union as a field operations officer was an honor, and that an abundance of confidence kept him from having any anxiety about the role.

“People who are confident think they’re right. Field operations officers know they’re right,” Coyle said.

As a field operations officer, Coyle’s job was to recruit foreign diplomats to supply intelligence to the agency. This often required months of building up trust before finally asking them to help the United States.

“You may think you’re good. You may have done well in the training. But when you ask that question, the adrenaline is flowing,” Coyle said. He described those moments as being one of the hardest parts of the job.

One of the other major challenges, according to Coyle, is being ultimately responsible for the lives of the people he would meet with.

“If I made a mistake, the guy I’m meeting with is gonna be shot within a month or two,” Coyle said. “You gotta be willing to play God with other people’s lives.”

During his time in an unnamed Eastern European country, Coyle recruited a diplomat who supplied intelligence because of an ideological conflict between himself and his home country.

As the man was getting ready to return home, he left a letter with Coyle and other CIA agents. It was addressed to his son, to be delivered if he never made it home.

“[He said,] ‘If I get caught, they’re gonna say I was a traitor,’” Coyle recalled.

Coyle said the emotional exchange was one example of the personal side of espionage that made him feel the true weight of his job.

While Coyle doesn’t know for sure what became of the diplomat after that, he hopes the agency never had to deliver that letter to his son.

“Hopefully, that letter’s still in an envelope in the CIA headquarters,” he said.

Coyle’s time at the CIA, however, wasn’t completely weighed down by heavy experiences such as that one. He often found himself in once-in-a-lifetime experiences. He’s found himself playing a game of basketball with then-U.S. Senator and former NBA star Bill Bradley, playing cricket in New Zealand and drinking vodka with Russians.

“I gave my liver for this country,” Coyle said with a laugh.

Nearly 30 years into his career, Coyle was getting tired from his role as an international operative.

“You’re always out there looking for the next target. That just gets tiresome after so many years,” Coyle said. He added that the repetitive role as a case officer and more management-focused responsibilities didn’t help.

By 2004, Coyle had learned of a program that paired agents with universities to allow them to teach classes as visiting professors. He decided to return to his alma mater, Indiana University, to teach a handful of classes with topics ranging from international intelligence to European national security to a seminar on creativity.

By 2006, he had officially stepped down from the CIA, and by 2017, Coyle retired from his position at the university. While his time as a spy may be over, his career has had a lasting impact on how he views the world.

“It makes you a little more cynical about human nature,” Coyle said.

He explained that these days, he finds himself being extremely skeptical of people who are overly friendly, especially if it seems that there’s nothing in it for them.

He also says the CIA taught him that few things in life are ever black and white. Instead, he says, life is usually gray.

“The last real example of something being black and white is World War II,” he said. Most foreign policy, he says, is not so clearly defined.

So what’s next for the man who’s seen and done just about everything under the sun? Gene and his wife Jan hope to see the rest of America, for starters.

The couple started their “see America” plan back in 2006 when they officially retired from the CIA. They’ve seen 43 states, but are hoping to make progress on the last seven soon.

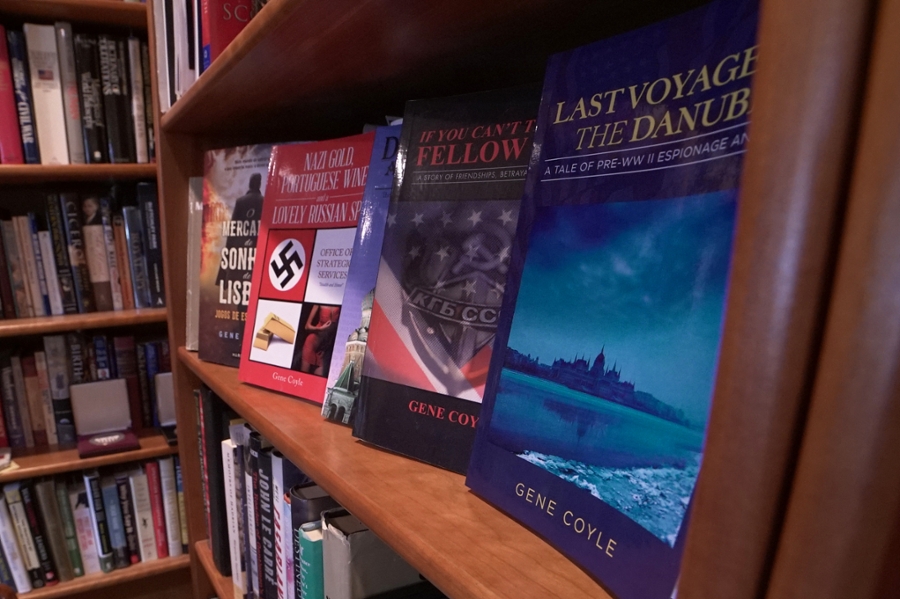

For now, he’s busy writing spy novels based, at least in part, on his own experiences, including “Nazi Gold, Portuguese Wine, and a Lovely Russian Spy” and “The Dream Merchant of Lisbon: The Game of Espionage.”

The latter’s title comes from what Coyle says was his role as a field operative.

“I was a dream merchant,” he said. “My job was to find out what your dream was and how I could sell it to you to get something out of you.”

The former operative says he doesn’t necessarily miss his old career, but he does find himself missing his former co-workers, as well as the adrenaline rush of working in the field.

He often jokingly compares his own career to his older brother’s, who became an engineer after studying at Purdue.

“My brother made more money, but I’ve had more fun,” Coyle said.