Long before streaming sites were packed with scores of documentaries, and even decades before shows like “Sesame Street” gave children easy access to informative programming, educational broadcasts were scarce.

But for much of the 20th century, an Indiana instructor was using radio to teach people on both sides of the airwaves. And despite his broad impact in the field, there’s a fair chance you haven’t heard of him.

Dr. Clarence “Doc” Morgan spent 35 years growing the radio division at Indiana State Teachers College (ITSC, since changed to Indiana State University) in Terre Haute while providing free educational content to children and his community at large.

According to Dr. Mary Myers, special adjunct at Regent University in Virginia Beach, Virginia, Doc Morgan is one of many pioneers across the country whose work in local radio is considered “hidden history.”

“When I began looking into the Doc Morgan story, the only thing that was available online was his obituary,” said Myers, who researched Morgan’s life for her dissertation. Myers said Morgan and many of his contemporaries “were prestigious in their locality and may have had some national prominence. But as the years passed, archives needed the storage space, and a lot of this history has been lost to destruction and time.”

Eighty-five years after Doc Morgan’s first broadcast at ITSC, his relative obscurity can’t overshadow his indelible mark on education, his students and his industry.

Morgan was born July 4, 1903, to a coal mining family in Linton, Indiana. From a very young age, Morgan was fascinated by radio; he would repurpose materials from around the house to make his own equipment and quickly became an avid ham radio operator.

With the prominence of coal mining in that area at the time, there was a strong possibility that Morgan would follow in his father’s footsteps in the mines. But according to Myers, Morgan’s mother pushed him toward receiving an education instead. That way, he could return home at a later date and become a schoolteacher, of which there was a shortage in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

In the early 20s, Morgan set off for DePauw University through the Rector Scholarship, which was the only way he could afford tuition. There, he obtained his broadcasting license and established radio station 9YJ with a couple friends. After graduation, he returned home to teach at his old high school, where he sponsored the student radio club.

Morgan enrolled in a graduate program at ITSC soon after, where he was hired by them to teach English. He then took a two-year leave of absence to earn his Doctor of Education degree from Indiana University, where he met his future wife, Ruth Laura Holaday.

By 1933, he was back at ITSC for a teaching position in the English department. But just one year later, word of his experience as a ham radio operator spread, and he was then tasked with growing the college’s radio department through local NBC affiliate WBOW.

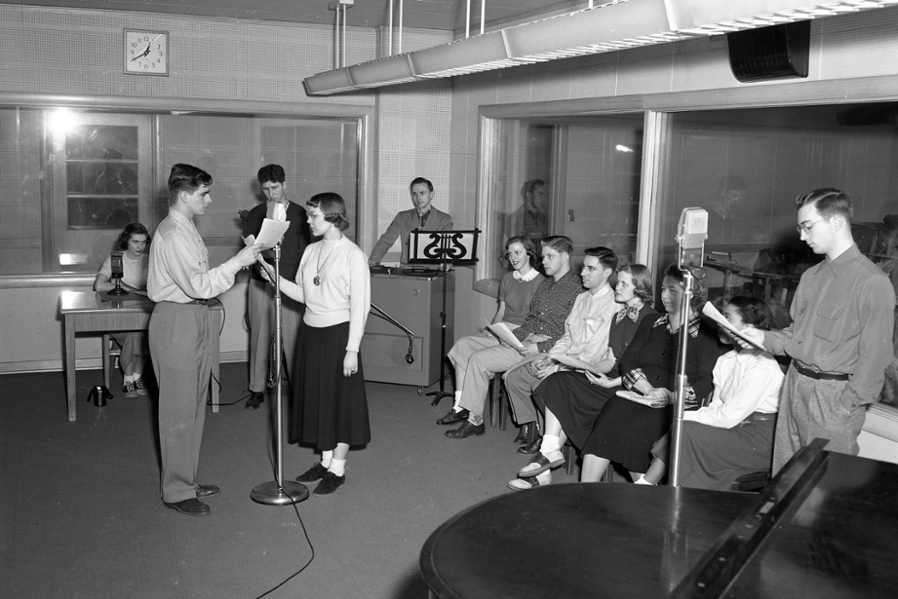

As a professor, Morgan rarely lectured in his classes. He was adamant about incorporating experiential learning, essentially letting his students run the station.

“He didn’t just believe that the listeners needed to learn something, he also thought those broadcasting needed to learn something from the experience as well,” Myers said. “He had students doing every aspect of the programs, from writing them to rehearsing to performing to casting them.”

This paid off in spades. Morgan was notorious in academic circles for churning out students who went on to hold successful careers in broadcasting, like Wanda Ramey, the first woman broadcaster in the western United States.

“His students were almost an assembly line,” said Dr. Thomas Morgan, Clarence Morgan’s son and retired professor of communications at the University of Central Florida. “They’d take off their caps and gowns and they would head off to work in a local radio station. He was widely sought out for advice on how to do what he did.”

Thomas Morgan recalled not seeing much of his father during the first five years of his life. The elder Doc Morgan was often off training Navy or Army Air Corps flyers in the use of radio for about six hours a day, and then he would spend the rest of his day teaching at the university. And on weekends, he’d walk folks in the Civil Air Patrol through using Morse code.

But when Thomas got a little older, he started to grasp the importance of his father’s work.

“Dad was no mean figure in and around Indiana,” Thomas Morgan said. “Every time I walked into a radio station, everyone said, ‘Oh, you’re Doc Morgan’s kid!’ He cast a very long shadow, even though he was a short guy.”

Thomas Morgan – the “younger version” of Doc Morgan, as he puts it – followed in his father’s footsteps to a very specific degree. While working at Murray State in Kentucky toward the beginning of his career, the university president pulled him aside and asked him to help build their non-commercial radio station, WKMS. While not originally what Thomas planned on, this led him on the path to a career in educational broadcasting. And yes, Thomas Morgan knows that trajectory sounds familiar.

When he told the elder Doc Morgan what happened, “he just laughed and laughed. He said, ‘That’s exactly what happened to me,’” Thomas said.

Around the time of Doc Morgan’s career at ISTC, most experimentation in radio was being done non-commercially at land grant universities. But according to Myers, more commercial broadcasters were starting to take interest in the medium as soon as they learned there was money to be made. That kicked off a struggle for control of the airwaves in the 20s and 30s.

That’s where children’s programming comes in. To advertisers, children were indirect consumers, and the ad space on their programs was incredibly valuable.

But Doc Morgan staunchly believed that children’s radio shouldn’t be reserved solely for adventure serials trying to sell them something. “He believed that people could be entertained and educated at the same time, which was a really innovative idea,” Myers said.

That idea came in the form of Morgan’s two staple series, “The Story Princess of the Music Box” (originally “The Fairy Princess of the Music Box”) and “The Peter Rabbit News Service.” The former featured morality tales under the guise of a fairy tale that ran for over 31 years. The latter incorporated Peter Rabbit characters in the fictional town of Forrestville as they reported on local and world news that pertained to children. According to Myers, several outlets including CBS noted that “The Peter Rabbit News Service” was the first and only news program geared specifically toward children.

Each show, between 15 minutes and an hour in length, reached anywhere from 60,000 to 120,000 listeners, with a broadcast footprint that extended through the Wabash Valley and into parts of eastern Illinois. Some shows were even used to supplement curricula of around 125 area public schools, according to Myers’ research.

The success of these radio programs led Morgan and ISTC to expand into television, via local commercial station WTHI.

In his 35-year career in ISTC’s radio department, Doc Morgan recorded over 10,000 live, student-produced radio and television programs. “That equates to over 200,000 free airtime minutes,” Myers said. “If you go back in time and calculate that for every single year, the amount of money that airtime would’ve cost under any other circumstance is staggering.”

That’s a monumental achievement, but it’s one for which Morgan would not have taken credit. Many who knew him say Doc Morgan’s standout quality was his humility, which inspired him to adopt the moniker of “Hoosier Schoolmaster of the Air” while at ISTC.

“Dad realized…that when Clarence Morgan’s name came at the end of the broadcast as the producer and director – to be blunt – there was jealousy in the faculty,” Thomas Morgan said.

Doc Morgan wasn’t interested in the credit, so he took the nickname, slightly altered from Edward Eggleston’s 1871 novel, “The Hoosier Schoolmaster.”

Morgan told his son, “’This accomplishes two things: It gets my name out of it…To me, it’s all about my students and it’s all about the university,’” Thomas recalled. Second, Doc Morgan intended for his successor to pick up the name so that it could live on. But when Morgan left ISU, so did the title.

Doc Morgan left ISTC in 1969, and he and his wife moved to Florida. There, he taught at Florida Atlantic University for 17 more years, before finally retiring in his 80s.

Clarence Morgan passed away in 1995 at the age of 92. In September of 2003, Morgan was posthumously inducted into the Indiana Broadcast Pioneers Hall of Fame, where Thomas Morgan accepted the award on his behalf. To this day, Thomas Morgan wears the gold microphone pin his father received at the induction.

According to Thomas Morgan, his father would have been content with his work in broadcasting being hidden history. After he began speaking with Myers for her research, Thomas told his wife, “I’m not sure Dad would be comfortable with this. Because he was always more interested in his students and his university getting credit.”

But when looking at Doc Morgan’s students and career in education, it’s impossible to separate them from the man behind them.

“There was a kind of ripple effect,” Thomas Morgan said, “with Dad at the center, throwing the stone in the pond.”

Dr. Myers will be speaking on Doc Morgan’s contributions to broadcasting at a celebration luncheon in Terre Haute on October 21. More info on the event can be found here. And the equipment Doc Morgan built as a teenager will soon be on display at the Vigo County Historical Society and Museum.