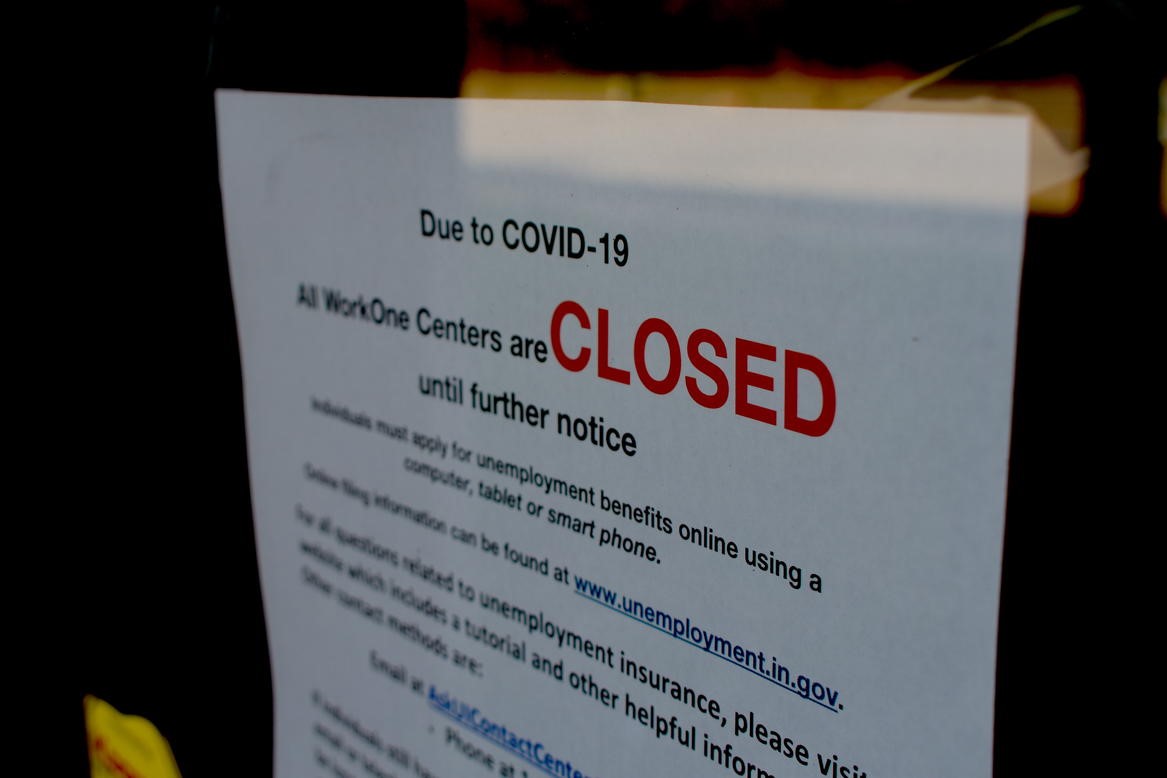

Workers prepare eight acres of a what would have been a corn field for a solar farm that is set to be operational by the end of 2019 in Kentland, IN. (Brock Turner, WFIU/WTIU News)

Hoosier farmers are making less money per acre than they have in years, but some are trading corn and soybeans for solar panels. Yet, the incentives for such projects vary greatly from state to state, and that makes it difficult for landowners to know what the policies to their specific locality are.

Among those farmers is Mark Simons. He’s been farming for 44 years, and like most midwestern farmers, the majority of his nearly 1,000 acres are corn and soybeans. Yet, he’s in the process of adding another crop into his operation—one that also relies on the weather.

“I think the word solar farm capsulizes it,” he says. “The electrons produced out there are just another crop. Instead of producing carbohydrates, we’re producing clean, renewable energy that goes on for a long time. The solar project out there can be producing power for forty years.”

Simons says he’ll have things up, running, and delivering electricity to the grid before the end of the year. It’s a sizeable investment, but he believes the payout in the long run will be more than worth it.

“It’s a multiple million-dollar investment in roughly eight acres,” Simons says.

He plans to install 4,500 modules, and is joining a growing number of farmers across the country who are hoping to diversify their revenue streams.

While there isn’t a single agency that keeps an exact count of the number of panels or farmers, experts say the number has increased significantly since the cost of solar panels decreased about ten years ago. That cost decrease made the math work for Simons.

“I’ve just got to compare the cost and the revenue. After the 15-year PPA [Power Purchase Agreement] is up, I’ll be 80 then. Hopefully my daughter will have it, and inherit it because the life time of it is 40-50 years.”

But as with most crops, producers are reliant upon a number of factors that determine the price they get. Simons says selling electricity back to the grid is filled with regulation that is elastic and changes over time. While his local electric providers are encouraging, Simons says it’s not that way in other parts of the state—and country.

Utilities, Regulators Hold Power To Solar Adoption And Production

“The utilities have a lot of power and a lot of money behind them,” he says. “They would like to see power production stay in their hands rather than making it more egalitarian.”

Simons adds, “The big money wants to maintain their control of the power system from generation through distribution.”

The end goal of utilities and electric providers is important to remember. While privately held producers and distributors are for-profit corporations, many providers in Indiana operate as Rural Electric Cooperatives. They serve a large portion of Hoosiers living in rural areas, and are non-profits. Their primary goal is to provide cheap power to less dense areas where the economics don’t make sense for private providers to operate.

Brian Anderson is the Director of Economic Development and Public Relations at the Wabash Valley Power Alliance — a nonprofit that provides electricity to individual member co-ops. They’re the ones that are transmitting and generating the electricity that could be powering your home.

“When we do a deal [with private land owners], we are always looking at how does this stand up on its own. We don’t want to overpay for power,” he says.

Part of that includes closely monitoring a complicated matrix that includes user affordability, sustainability, and reliability.

“We don’t want to overpay for power. We’re always thinking about that long-term price stability. Maybe not what’s in the best interest of one particular member, but the 330,000 members that are a part of our service.”

Anderson says rural population declines and changes in densities has an impact on the power supply and the presence of renewables.

In Face Of Incentive Cuts, Solar Energy Production Has Grown

Two years ago Indiana ended its net metering policy which incentivized solar energy production by providing solar customers the higher retail rate instead of a lower wholesale rate for excess energy they deliver back to the grid. Despite that policy shift, Anderson says he’s seen more people interested in solar.

“We’ve seen an uptick in interest from landowners in general looking for sustainable solutions and making some of those economics work.”

Despite that shift and declining prices of equipment, experts say it’s unlikely Indiana will return to net metering. They say it is important to craft durable policies that won’t change over time and will span across elections.

“We don’t have evidence yet as to what model is the best,” Sanya Carley, a Professor at Indiana University’s O’Neil School of Public and Environmental Affairs says.

However, she believes states should still be cognizant of the policy changes they decide to adopt. “I do think it’s really important for states to think through their individual kinds of charges and what’s necessary and of value.”

Carley says despite changing state policy some companies are being mindful of where their electricity is coming from. “We’ve seen a proliferation of companies stepping up and saying ‘we will do 100 percent renewable energy or we will make sure we put solar panels on all of our warehouses.’

She says that’s even the case in states that have rolled back or been hesitant to adopt renewable energy incentives.

“In absence of strong policy leadership, we see companies actually stepping up,” she says. “There are leaders and laggards there will be some companies and some states that lag behind the others and in those cases, yes, it probably will happen it will just happen much later than those that are taking a leadership role.”

Carley says the cost of solar has decreased significantly in recent years and the technology has continued to improve.

While Simons admits the policies in Illinois make it more economical, he’s still excited to get these eight acres in Indiana operational.

“If you’re producing electricity at a high enough rate your payback is much better on solar,” he says. “And it’s much better in Illinois because they have renewable energy credits to help defray the initial startup costs of a solar system,” he says “it’d be nice if Indiana [the state where all of his current project sits] had some of those incentives.”

But Simons isn’t complaining too much. “There’s more money in producing electrons than in producing corn and soybeans at this time, particularly at this time,” he chuckles.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly spelled IU Professor Sanya Carley's first name. This story has been updated to reflect that change.