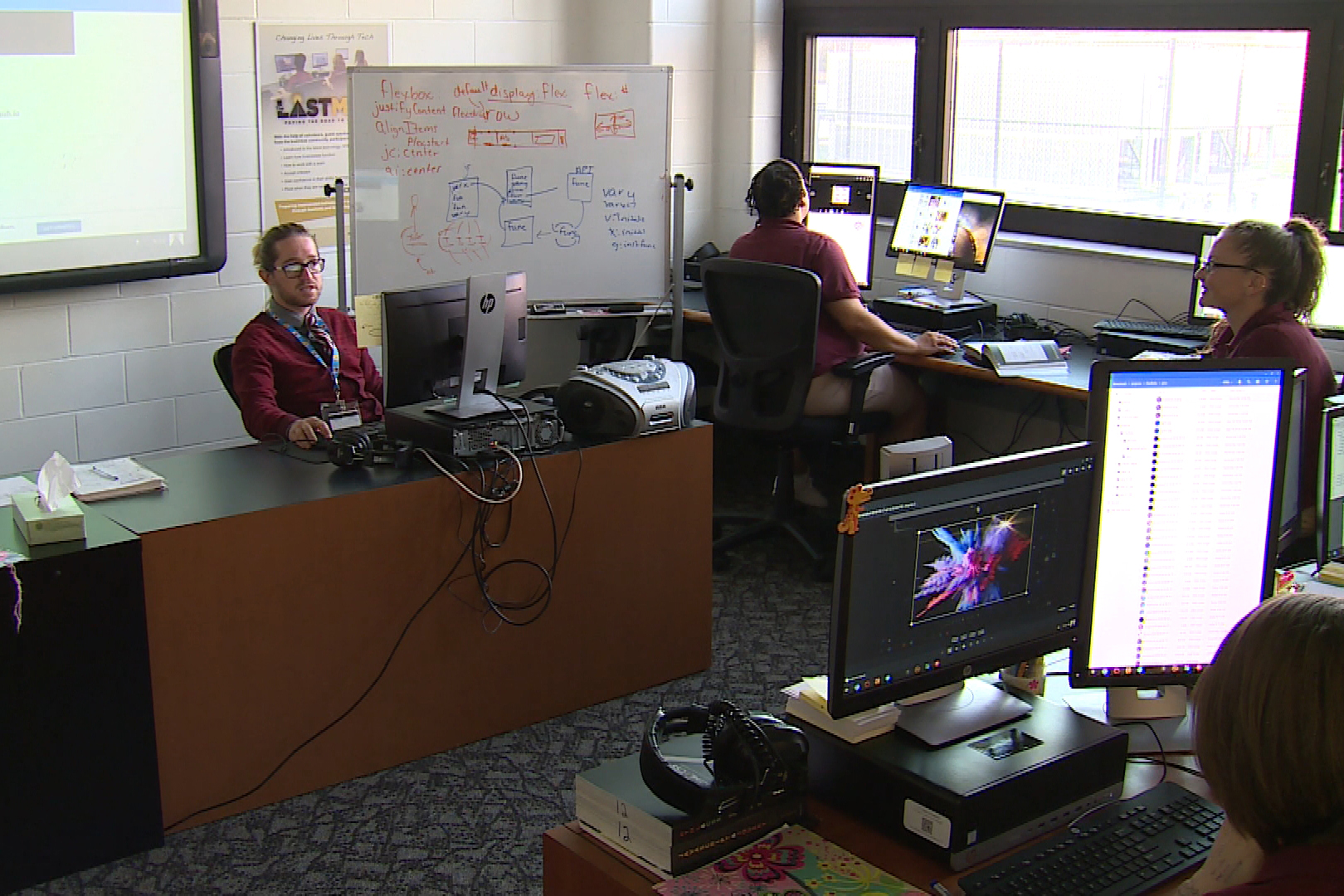

Indiana launched the Last Mile at Indiana Women's Prison earlier this year. The DOC plans to expand the program to other facilities (Steve Burns, WFIU/WTIU News).

As Governor Eric Holcomb continues to focus on filling thousands of jobs in Indiana, he’s looking to the state’s prisons for help.

He touched on that priority during his State of the State address earlier this year.

"And, we won’t forget the 27,000 Hoosiers in our prison system," Holcomb said. "By 2020, we’ll graduate at least 1,000 inmates annually in certificate programs that will lead to good jobs when they get out."

The Department of Correction is increasing its vocational training programs to align with those workforce development goals. That includes the creation of two new programs in just the past year.

Coding Class Teaches Job Skills, Reduces Recidivism

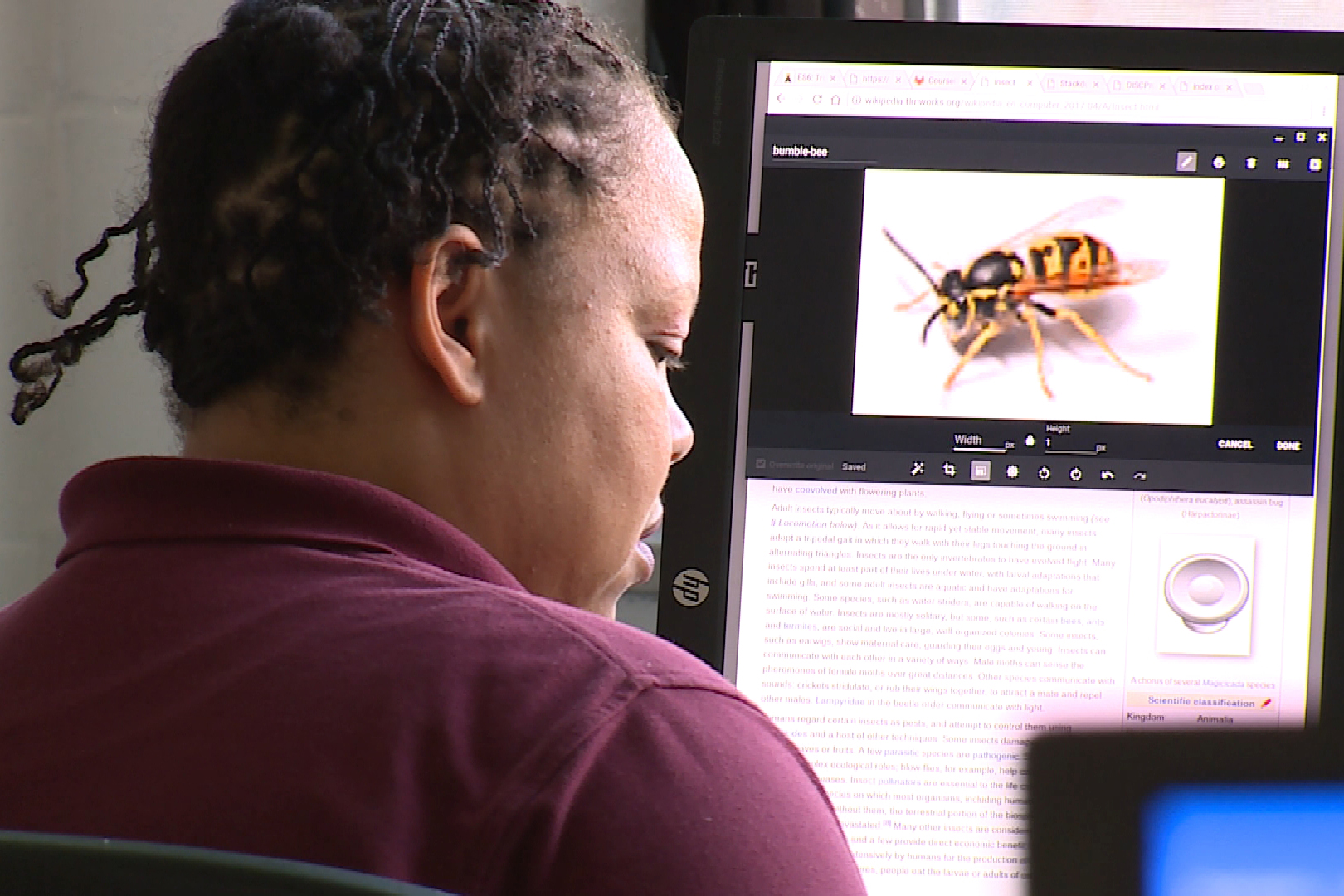

Stacy Jennings is typing what may look to many like a foreign language. A string of several words and symbols make its way across her screen as she works on her website. She's writing HTML code, which helps determine how the text on her webpage will appear.

"For me, it takes a little long because I like to understand what I’m doing and why I’m doing it," Jennings says.

Jennings is incarcerated at the Indiana Women’s Prison in Indianapolis.

She’s been in and out of the system for years, and says she never found her stride when reentering society.

"I was always involved in school, education things," Jennings says. "But, when I got home, I couldn't utilize it."

But, this time, she feels different. She's part of the inaugural class in Indiana's Last Mile program. The nonprofit is based in San Francisco and provides coding training in prisons. The Indiana Women's Prison is the first facility outside of California to get the program.

The one-year course teaches women HTML, CSS and Javascript.

Jennings says she thinks it's giving her the skills to finally keep her from coming back.

"For one, it will help you be employed and be able to support yourself financially," she says. "And, that helps you get over some of the obstacles that you face when you go home."

The goal is to arm women with the skills needed to land a job as a computer programmer upon their release. And that has a direct impact on recidivism.

"We’re trying to empower the students, all the women in there that you’ve seen, give them the ability to not come back here," says Quincy Williams, an instructor with the Indiana Women's Prison Last Mile program.

According to the DOC, nearly 34 percent of offenders returned to prison within three years of their release date in 2017.

But at other facilities with the Last Mile, there’s a 0 percent recidivism rate among graduates – and 100 percent get a job or continue their education after their release.

"Correctional education prepares you to enter the workforce," says John Nally, director of education for the IDOC. "But when you get into the workforce, and you get a job within 90 days after that, you retain employment, your recidivism rate, it’s just a perfect alligator’s mouth. As your education goes up, your employment goes up. As your employment goes up, your recidivism goes down."

DOC Focusing More On National Certficate Programs

The Last Mile program is part of a shift towards more hands-on training in in-demand fields at the IDOC.

That includes focusing on career paths with national certifications, like welding.

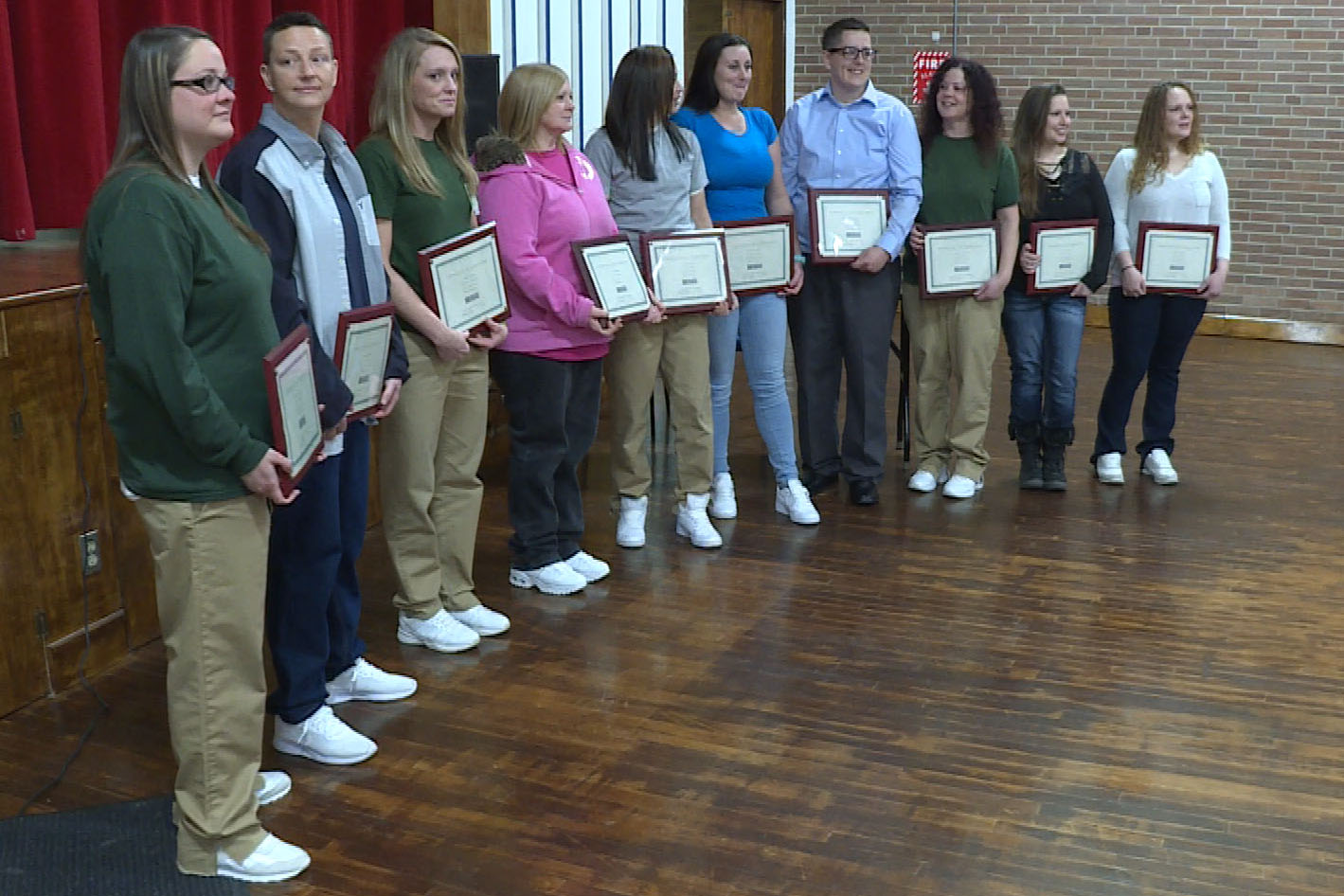

Earlier this year, ten women graduated from a new program at Madison Correctional Facility. They underwent 80 hours of hands-on training to obtain an American Welding Society certificate.

"It’s one thing to say I did welding while I was incarcerated," says Sherm Johnson, director of the IDOC's employment readiness program. "It’s another thing to say I learned welding while I was incarcerated and I earned an American Welding Society certificate. The employer knows what you know, knows your skill level as opposed to you the released offender stating, ‘Well, I think I can do that.’"

And, those types of programs can also help offenders stay out of trouble while they're still incarcerated.

Emilee Bowyer says the Last Mile gives her a sense of pride she hasn't had before.

"Right now I'm working a tic tac toe game," Bowyer says. "And, you wouldn't think it would be that difficult, because it's click a button, click a button. But, there's so much more that goes into it than that."

She still has a few years before she could be released, but Bowyer hopes to move to a bigger city and get a job as a software engineer. She thinks being in a new environment, armed with new skills, will help her succeed.

"I want to wake up and want to go to work," she says. "And, so, I think that's where I'm headed."

Both the welding and coding programs are only offered at the Madison Correctional Facility and Indiana Women's Prison, respectively. But, the IDOC hopes to expand them.