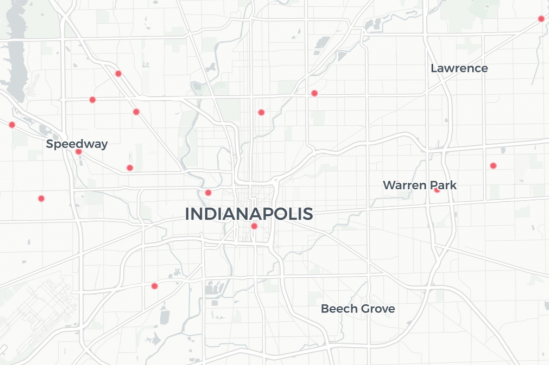

Marion County's most Black neighborhoods only had three of the county's 30 testing sites as of June 25. (Courtesy photo)

This spring, as it became clear COVID-19 was hitting African-Americans especially hard, Indianapolis-area health officials vowed to set up testing sites in “hotspot” neighborhoods. One opened in predominantly Black Arlington Woods, at a respected local institution: Eastern Star Church.

“Obviously this is a community and area that has health disparities. And so we’re here to serve the community,” Virgil Madden of the Marion County Public Health Department said when the site opened in late-April. “More testing is important to get a clearer picture of the virus’ impact.”

But a few weeks later, the testing site closed, leaving community leaders frustrated. The shutdown came even as national studies showed that Black patients suffered more serious complications and higher death rates from COVID-19.

Eastern Star Pastor Jeffrey Johnson Sr. says the site was consistently busy, and he expected it to be open for several months. “Why are we withholding resources from this community that you told us that this is the area that's being hit the hardest by [COVID-19]?” he says.

That problem is repeated across the county which includes Indianapolis, according to a Side Effects Public Media analysis of testing sites.

The analysis found that neighborhoods with the highest percentage of Black residents had only three of the 30 testing sites in the county. Most sites were concentrated in neighborhoods with more white residents.

The analysis included sites operated by state and county health departments as well as local hospitals and private companies.

Breanca Merritt, director of Indiana University's Center for Research on Inclusion and Social Policy, says the scarcity of testing sites in Indianapolis area’s predominantly Black neighborhoods is an unfortunate trend.

“Time and time again, we see that these neighborhoods are consistently under-resourced, whether it's home values, school quality,” Merritt says. “So, you know, it's definitely a trend that persists across a variety of issues.”

Dr. Virginia Caine, medical director for the Marion County Public Health Department, says the agency doesn’t have the manpower to test in all county hotspots. She adds that it has had to respond to other neighborhoods and groups with high rates of the virus — like an outbreak among Burmese immigrants.

“So my goal is to try to get testing eventually through all of our hotspots to Marion County. We have not accomplished that,” Caine says. “But we are working on getting to that point.”

Her department operates one of the three testing sites in city neighborhoods with the highest percentage of Black residents. Caine says at this location, as well as the department’s others, they are testing more people of color than are represented in county demographics.

“I honestly think based on the availability of testing and staffing that I have, I honestly think we're doing a good job of making it accessible and available for folks who want to get testing for COVID-19,” she says.

The county public health department operates three testing sites.

Merritt says that instead of an even distribution of testing sites among race and income, it may be more effective to concentrate additional testing sites in harder hit areas.

“In the case of COVID, it's hitting black communities disproportionately. So our response has to be at an equal proportion to what they're experiencing,” she says. “And so if we don't meet that with the same impact, then we're going to continue to see these issues persist.”

SAVI, a research organization from IUPUI and the Polis Center, found that Black residents of Marion County tested positive for COVID-19 at twice the rate of whites. Black residents are also more likely to suffer more serious health consequences because of the virus, and increased death rates.

People of color are not genetically more likely to catch COVID-19, health experts say. But they face conditions that increase their exposure — like essential jobs and denser neighborhoods. They also are more likely to suffer from pre-existing conditions, such as diabetes or obesity, that can cause complications with COVID-19.

The COVID-19 testing sites included in Side Effects’ analysis include sites run by the Indiana State Department of Health, the Marion County Health Department, local hospital networks, and privately managed sites such as CVS. The analysis did not include mobile, temporary testing sites, or those in doctors’ offices.

Overall, Black residents account for about 29% of the county’s population. As of June 25, Side Effects’ analysis found three testing sites in neighborhoods where Black people were at least 48.8% of the population. Most of the 30 sites in Marion County were in neighborhoods where the percentage of Black residents was much lower.

The lack of testing sites in neighborhoods with lots of Black residents has left some experts and community leaders concerned there are undetected COVID-19 outbreaks. They also worry this could further widen health disparities in the Black community.

And Arlington Woods isn’t the only majority-Black neighborhood asking for a COVID-19 testing site.

Linda Ellis is president of a neighborhood group called the Northwest Neighborhood Planning Development Corp. She says she’s been asking for a testing site in the neighborhood near Crown Hill cemetery, and is concerned there could be an undetected outbreak.

“They’re concerned about this resurgence, and prevention starts now,” Ellis says.

Despite previous shortages of testing supplies, Indiana’s Health Commissioner Dr. Kristina Box said recently that testing is now available to any Hoosier who wants it.

Dr. Scheri-Lyn Makombe, medical director of Jane Pauley Community Health Center, says this information may have been poorly communicated to communities of color.

“When COVID broke, the message from everyone, you know, government levels, state levels, etc, was see your doctor for a test. Right? And back then the doctor didn't have the test,” she says. “So I think in a lot of ways, it's very true that the message has not been updated.”

Makombe also says that with time, the urgency for a test has diminished, and that her own patients have been surprised at more available testing. She says her clinic would send patients to Eastern Star Church.

She also says that for many county residents, access to transportation has been a significant barrier to getting a COVID-19 test.

Caine says the county public health department is looking to add testing sites — including reopening one in the Arlington Woods neighborhood.

“So I've made sure you don't require a doctor's order, and definitely the testing is free," she says. "Because a lot of our population don't always have a primary care provider. You know, they get their services at the emergency room on average.”

In a press release, the county public health department said it would maintain communication with Eastern Star Church leaders to locate individuals who need access to testing.

Pastor Johnson says that has not been the case.

Caine says there may have been a miscommunication while trying to reach Johnson.

Reporting and data help from Side Effects' Lauren Bavis, Brittani Howell and Darian Benson. Additional assistance from NPR Data team's Sean McMinn and Ruth Talbot.

This story was produced by Side Effects Public Media, a news collaborative covering public health.

For the latest news and resources about COVID-19, bookmark our Coronavirus In Indiana page here.

9(MDIwNjQ2MTYzMDE0NDM1NTQ0OThlYjEzMg001))