What Happens If Kids Opt Out of ISTEP+?

The road to this year’s ISTEP+ test has been bumpy. Recurring problems with technology and last-minute legislative changes to trim the length of the test have only added to the frustrations many Hoosier parents feel about the stressful effects of standardized testing.

Many parents are deciding to “opt out,” or withdraw their child from this year’s pool of test-takers.

But that decision could have serious repercussions for teachers, schools and even the state.

- Opt Out Adds To Test Stress For School LeadersRecent ISTEP+ drama has only added to concerns over the stressful effects of standardized testing ¬– leading many parents to choose to withdraw their child from this year’s pool of test-takers. But, as StateImpact Indiana’s Rachel Morello reports, the decision to “opt out” could have serious repercussions for teachers, schools and even the state. Download

When Children Worry, Parents Act

Caswell Woodruff was a third grader at Bloomfield Elementary School last year when he began relaying ISTEP+ horror stories to his mother, Resa.

Bloomfield parent Resa Woodruff displays a picture of her son Caswell, 9. (Photo Credit: Barbara Harrington/WTIU News)

“He would tell me some of the things the teachers would say about ‘you have to pass this,’” Woodruff says. “He would just tell me some of the kids were worried and concerned and just the stresses of the environment in the classroom because of the testing.”

Worried for her son, Woodruff began researching, finding any information she could about Indiana’s standardized tests – and what she found scared her, too.

“The more research we did on the subject, the more we wanted to opt our child out of the test,” Woodruff says. “They’re not a reliable and accurate assessment of our child’s developmental growth.”

Indianapolis parent MaryAnn Schlegel Ruegger shared a similar experience. She began noticing changes in her daughter Isa’s afterschool behavior in 2012, when her third grade class at the Indianapolis Project School began ISTEP+ prep.

“She had difficulty sleeping, being very tired, a lot more acting out, a lot more crying – you name the stress behavior that you can think of and I was seeing it,” Ruegger says.

Driven by worry for their children’s health, both women decided to take action: each opted her child out of the test. It was simple – all it took was a letter to the school principal explaining the decision and asking that the children be given alternate activities during the testing period.

Interest Grows in Indiana

Support for opting out of the exam this year is growing.

A Facebook page dedicated to the cause tripled in followers this month – “likes” increased by 20 percent in the last week alone.

And it’s easy to understand why, with recent technology issues, flare-up over the length of this year’s assessment and more drama among top government officials in taking action to trim the test.

“When we did it, it wasn’t a typical thing to do,” Ruegger says. “I’m hearing the same kind of concerns that I had that year now coming to me from parents that I know in Carmel and in Fishers and in Zionsville, and in my rural hometown.”

And in Tracy Caddell’s district, ten miles east of Kokomo. Caddell is superintendent for the Eastern Howard School Corporation, and last Friday – one week before his district planned to begin testing – he sent out this distressed message on Twitter:

@StateImpactIN Parents opting out of the ISTEP test today. what a mess

— Dr. Tracy Caddell (@Cometcentral) February 20, 2015

Caddell says until this year, his schools have always had full participation on ISTEP+.

“A few kids opting out can really affect your achievement,” Caddell says. “If this is happening statewide, what are we expected to do?”

What’s The Potential Aftermath?

There’s no law on the books in Indiana about opting out. The Department of Education lets each district decide how to handle it individually. But, there are consequences if enough students don’t participate in each district.

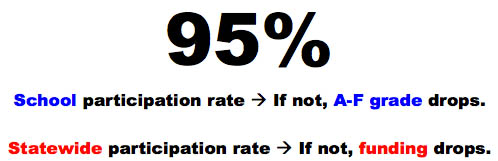

“It can have a very big impact on state accountability, which means a school’s A-F grade,” DOE spokesperson Daniel Altman says. “If schools don’t have 95 percent of students taking the assessment, that can knock their grade down an entire letter, or potentially even more depending on the circumstance.”

Ninety-five percent is the magic number for federal requirements, too. The current version of No Child Left Behind requires 95 percent participation statewide – or else Indiana could see a serious reduction in federal funding.

Don’t forget: test scores factor into things such as teacher evaluations and teacher pay, too.

“At some of the smaller schools, even if you’re just talking about a couple of children that end up not taking the assessment, that can have a really significant impact not just on the school but on the community,” Altman says.

School leaders say they’re worried, but they don’t feel like they have much choice in the matter. Tracy Caddell instructed his local principals to allow students to opt out, despite the seemingly inevitable impact.

“What I imagine is going to happen is this is going to grow as we do more and more ISTEP+ testing throughout the week, because there’s parents obviously going to share with other parents that they’re opting out,” Caddell says with a sigh. “I do understand why parents are frustrated. I can really sympathize with them. It’s just, I don’t know how to fix the problem.”

What Would You Do?

Isa Ruegger no longer attends the school where she opted out in 2012, because it closed in 2013.

—MaryAnn Schlegel Ruegger, parent

“I have regretted it for the sake of the school, because the closing was very sudden,” Ruegger says. “It was very disruptive for our family, it was probably the biggest crises we’ve ever had,”

Despite her family’s experience, Ruegger says she is neither a proponent nor an opponent for opting out. Instead, she emphasizes the need for parents to voice their concerns about testing where they can best be heard.

Fourth grader Isa Ruegger completes a page in her workbook at home. (Photo Credit: MaryAnn Schlegel Ruegger)

“I didn’t fully know maybe what other options I might have had, which would not have taken care of the test that year for her, or maybe the next, but would have made a different for the future,” Ruegger says. “I could have instead gotten in my car and driven to the Statehouse, and I could have gone and met with Senators and Representatives and their staff and told them what problems were out there and what we were thinking about, perhaps, and how I thought they needed to vote to change that.”

Knowing the potential impact her decision could have, Resa Woodruff still plans to opt her son out of the test again this year. She says for parents toying with the option, this is the year to do it.

“You have to do what’s best for your child, and if that includes opting out, then so be it,” Woodruff says. “You are federally protected, and you have that choice.”

The Department of Education will be able to track the number of students opting out at each school once finalized tests are collected. Once tests are graded, that data will become one of the factors that comes into play in calculating this year’s A-F school grades.