Why A Referendum Might Be The Only Way To Save Hamilton Community Schools

Elle Moxley / StateImpact Indiana

Superintendent Jon Willman, right, and members of the Hamilton Community School Board take questions about the referendum during a public meeting on Oct. 17, 2012. The school corporation is pursuing a property tax increase of 44 cents per $100 of assessed valuation to cover operating expenses like teacher salaries.

For months now, Hamilton Community Schools Superintendent Jon Willman has been beating the same drum: if district voters don’t raise their own property taxes this November, the district must merge with another school corporation.

The last few years have been hard for the northeastern Indiana school corporation — one of the smallest in the state. Enrollment started falling about the same time the state changed the funding formula so tuition support would follow the student. Now Willman says he can’t make cuts fast enough to keep pace with shrinking revenue.

“But we just don’t have any fluff,” says Willman. “If we were going to cut the people we need to balance our book, we wouldn’t be able to provide the educational opportunities we need for the students at Hamilton. You might as well consolidate.”

- Referendum Or Consolidation: How Hamilton Is Trying To Sell A Property Tax Increase To VotersStateImpact Indiana‘s Elle Moxley explains why a cash-strapped school corporation in northeastern Indiana will try to consolidate with another district if its referendum fails at the polls.Download

Superintendent Says Small Schools Can’t Make The Same Cuts

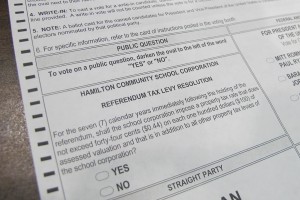

State law changed a few years ago so voters get to weigh in when districts wanted to build new schools or renovate old ones. But corporations can also pursue referenda to bolster the general fund. Hamilton is trying to sell voters on a property tax increase of 44 cents per $100 of assessed valuation to cover expenses like teachers salaries and operating costs.

Willman says Hamilton has already cut support staff, offered early retirement incentives and combined several positions. They’ve reached the point where most districts would start laying off teachers. But Willman says he can’t do that because Hamilton is so small. Just over 400 students attend the school, and the district employs just 35 teachers. That means there’s only one person teaching most subjects.“There’s no English teacher I can cut,” says Willman. “It’s not like I have six English teachers at the high school and by being creative with the schedule I could cut back on five and make do.”

In other words, Hamilton has reached a point where eliminating a position means they wouldn’t be providing the educational services the state mandates.

A few years ago, Willman says rumors started circulating that small schools would have to consolidate and students began to leave, taking state tuition support with them.

Willman says the $2.8 million the school will get from the state this year isn’t enough to cover operating expenses.

“You can be very frugal and save 10-, 15-, 20-thousand, but what we’re looking at is a shortfall of $1.5 million on an annual basis,” Willman says. “There’s no way for our size of school system to do that.”

Economist Says It’s Hard To Predict What Referenda Will Pass

Elle Moxley / StateImpact Indiana

Only a handful of people attended a public meeting to discuss the referendum on Oct. 17, 2012. Hamilton Superintendent Jon Willman says he's not surprised turnout was low because the district has already hosted several information session.

One of the reasons Gov. Mitch Daniels has pushed for consolidation is bigger schools can achieve economies of scale that smaller schools can’t.

Research from across the country suggests the ideal size for a school corporation is between 2,000 and 6,000 students, says Larry Deboer, a Purdue professor who studies property taxes in rural areas like Hamilton.

“If you want your small school corporation, you’ve got to recognize they’re more expensive to operate, and you’re gonna have to pay more in property taxes,” says Deboer.

In the last three years, 37 Indiana school corporations have asked for a property tax increase to bolster their general fund. Voters have passed about half of those increases. But very few districts are actually in a position where they’d have to consolidate if a ballot initiative failed, says Deboer.

One thing that might help Hamilton pass its referendum: Lake Hamilton. Deboer says vacation homes are a lot like corporate business property.

—Larry Deboer, Purdue economist

“Those owners probably live somewhere else, not in your school corporation, so they’re not around to vote no if they’re inclined to do so,” he says.

Deboer can rattle off all the factors that can influence the outcome of a referendum election, but he says it’s impossible to predict results with any kind of certainty.

“There are also unmeasureable factors,” he says. “The sheer popularity of the superintendent, which I cannot possibly measure, probably matters.”

But perhaps most importantly, Deboer says the quality of the campaign matters.

If Referendum Doesn’t Pass, Consolidation Would Increase Property Taxes Anyway

Hamilton has held a series of public meetings about the referendum so voters understand why the district is pursuing such a steep hike. The three school districts that passed general fund referenda in the spring asked for increases of 19, 22 and 24 cents.

But right now, Hamilton’s 44-cent property tax rate is really, really low — lower than all of the surrounding school districts, lower than all but five school districts in the state. Even if the tax increase passes and school property taxes double, Hamilton’s rate will be below the state average and only then on par with its four neighbors.

Elle Moxley / StateImpact Indiana

The Hamilton Community School Corporation referendum will appear on the ballot in Steuben and DeKalb counties on Nov. 6.

That’s important because if the referendum doesn’t pass, Hamilton might have to consolidate with one of the four districts surrounding it: MSD Steuben County, Garrett-Keyser-Butler, DeKalb County Eastern or DeKalb County Central.

In those districts, property taxes are higher than they are in Hamilton presently.

“So if people are gonna vote strictly on their pocketbooks, then they’re going to support the referendum because they’ll still pay less than if we consolidate with another school,” says Willman.

But consolidation isn’t a guarantee. Hamilton would need the consent of one of the surrounding school corporations, which it hasn’t sought. Willman says he doesn’t want to send the wrong message to voters, but that doesn’t mean the surrounding school districts aren’t watching.

“It’s too early to have that discussion,” says DeKalb Eastern Superintendent Jeffrey Stephens. “Hamilton still has time to look at other options.”

That’s true. Hamilton has enough in its rainy day fund to make up the shortfall in state funding this year, but if both the referendum and consolidation fail, it’s unclear what would happen.

The district would likely have to appear before the Distressed Unit Appeals Board when it runs out of money. The remedy the board can offer is really specific — a low-interest loan. Dennis Costerison, executive director of the Indiana Association of School Business Officials, says that likely wouldn’t help Hamilton in the long run.

And there’s no mechanism in Indiana law that allows the state to take over a cash-strapped district.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download