Indy Monthly: Ritz Spokesperson Searched Bennett Email Files, Denies Leaking Story

Kyle Stokes / StateImpact Indiana

State superintendent Glenda Ritz and her predecessor, Tony Bennett.

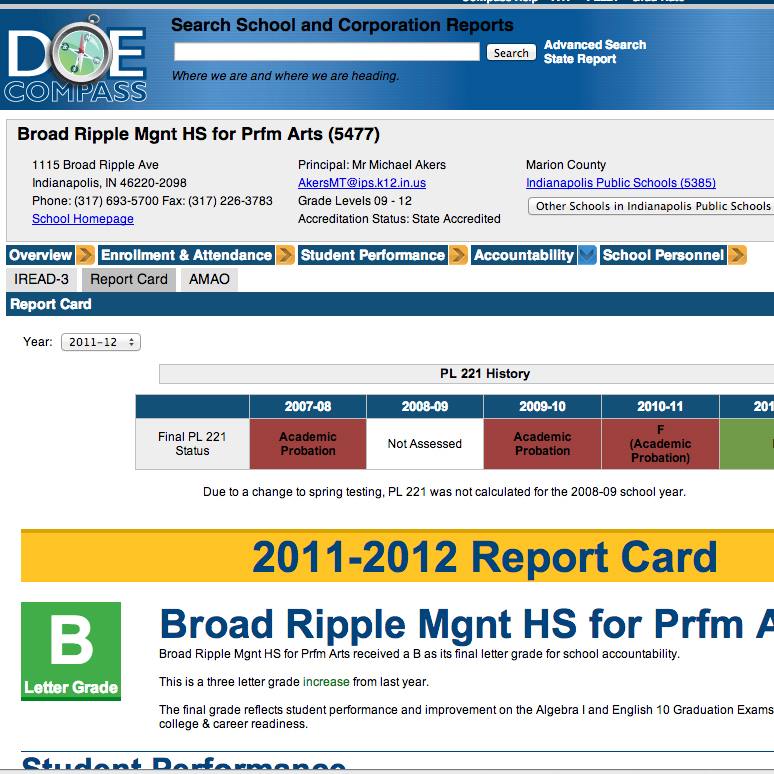

State superintendent Glenda Ritz‘s chief spokesperson David Galvin took three to four weeks to personally scan through “tens of thousands” of emails from the administration of her predecessor, Tony Bennett, reports Adam Wren in his latest for Indianapolis Monthly.

The piece doesn’t reveal how AP reporter Tom LoBianco knew to ask for emails that revealed Bennett’s last-minute changes to the state’s A-F formula or his possible use of state resources for campaign purposes.

But there are several compelling tidbits. For instance, after getting tipped off there might have been problems with the 2012 A-F grades, Galvin asked the Department of Education’s IT department for the email inboxes of Bennett’s closest aides. Wren writes:

Over the next three to four weeks, Galvin estimates, he spent between 18 and 20 hours studying the e-mails. “After work, after hours, I would do word searches on some of the personnel who were involved in the development of A–F,” he says. That Galvin volunteers he only examined the e-mails outside of office hours is an interesting detail: Indiana law bars staffers from so-called “ghost employment,” spending their workday hours or using state resources to do political work—a possible felony charge that can send a person to prison for up to three years (and an accusation that would later be leveled by some at Bennett). Did Galvin look at the e-mails only outside of work because he suspected he would find ammunition that could be used against a political foe? “Honestly, I didn’t anticipate finding political stuff in the beginning,” he says, “because I have been taught from my time [as an aide] with Mayor Goodnight of Kokomo that party politics is not to be part of your discussion while you’re on campus.”

Of course, Galvin had found emails that would eventually cost Bennett his job as Florida’s state schools chief. But Galvin denies either he or his deputy, Daniel Altman, coached LoBianco which emails to request in the course of his reporting.

Many Bennett allies speculate LoBianco must have had help from an unnamed source within Ritz’s Department of Education. Wren continues:

Interestingly, no e-mails have yet surfaced that seem dull—there were no “hey, let’s go to lunch” missives over the course of nearly four years of correspondence between Bennett and Daniels, political teammates who by all accounts worked closely together. Luke Britt, the state’s public-access counselor appointed by Republican Governor Mike Pence, says the Ritz administration could have curated the records they sent to LoBianco, based on the rationale that they would have otherwise inundated the reporter. But inside the ranks of the Ritz administration, some troops have grown unsettled about what they see as unnecessary hardball tactics—the way reconstructed e-mails were mined to dig up dirt on the previous administration, as well as how public-records requests were handled.

For them, an unanswered question simmers: Why would Galvin have spent so much time with old e-mails unless he was looking for dead bodies?