What's The Lesson Of The Bennett Emails For States That Issue A-F Grades?

Kyle Stokes / StateImpact Indiana

Former Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Bennett has stepped down as Florida Education Commissioner after the Associated Press released emails indicated his staff changed the letter grades of more than a dozen schools.

A pair of independent evaluators will assess the accuracy of letter grades schools received from the state in 2012.

The announcement came the day after former state superintendent Tony Bennett resigned his post as Florida Education Commissioner following the release of emails showing his staff changed the letter grades for more than a dozen charter schools during his time in Indiana.

In a statement, Gov. Mike Pence said the independent review is necessary to ensure the integrity of the school grading system the state started using last year. Restoring public confidence in the system, he added, is the first step in a scheduled rewrite of the A-F accountability metrics already underway.

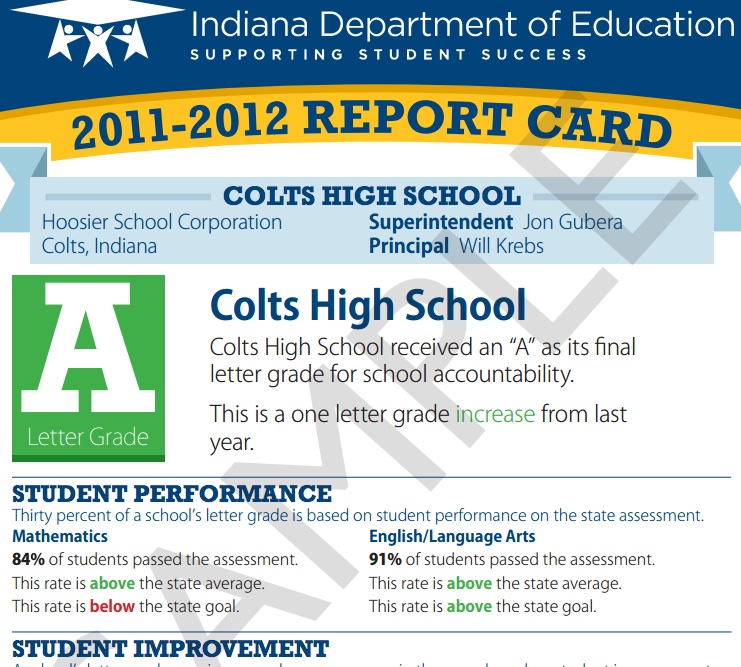

An increasing number of states are using letter grades to rate schools because they’re easy for parents — and taxpayers — to understand.

“There is a very clear tradeoff here,” says Mike Petrilli, vice president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. “The downside is you lose a lot of nuance.”

- Is An A-F Accountability System Right For Indiana?StateImpact Indiana‘s Elle Moxley explains the benefits — and the pitfalls — of assigning schools letter grades in the wake of the Tony Bennett email controversy. Download

‘Behind These Letter Grades Are A Lot Of Judgment Calls’

Let’s be clear: Petrilli has long supported many of Bennett’s education initiatives. The Fordham Institute even named Bennett its “Education Reform Idol” back in 2011.

Petrilli says, on its face, what Bennett says he did to tweak the letter grades of Christel House Academy and a dozen other charter schools isn’t problematic.

Screenshot / The Florida Channel

A screenshot from Florida's public affairs television channel showing Tony Bennett, former Indiana state superintendent, resigning from Florida's top education post Thursday.

“I think in fact he did exactly what you’d want a public official to do,” Petrilli told StateImpact Wednesday, before Bennett resigned. “He saw a problem with a high stakes accountability system, he saw that there was something strange going on in the algorithm, and he dug in to see how they could fix it.”

Emails obtained by the Associated Press show Bennett and his staff scrambled to change the metrics of the state’s accountability system when it became clear a charter schools run by a prominent Republican donor would receive a C. But even as he resigned as Florida’s Education Commissioner, Bennett defended his decision. He told StateImpact if Christel House didn’t get an A, no one would trust the state’s new accountability system.

That, too, makes sense, writes Andy Rotherham, blogs at Eduwonk and co-founded Bellwether Education Partners, a non-profit organization. Christel House had always scored well on state tests in the past.

“Indiana had an accountability system prior to this,” Rotherham told StateImpact. “It was not necessarily simple enough for parents, which is one of the reasons the A-F grading systems are very appealing.”

Rotherham says it would have behooved Bennett to be more transparent about the changes he had his staff make. But Petrilli says in all likelihood, the former state superintendent made a judgement call.

“He had spent months (and much political capital) building an A–F accountability system for Indiana’s schools,” Petrilli wrote last week on Fordham’s Education Gadfly blog. “These systems are as much art as science (more akin to baking cookies than designing a computer), and when they tried out the recipe the first time, it flopped.”But here’s where it gets messy. Petrilli says Indiana and the 14 other states now using A-F accountability systems don’t all calculate letter grades using the same metrics. The focus here is on growth — a complicated calculation that compares Indiana students to their peers across the state. It’s so hard to explain that even before the Bennett emails came out, state lawmakers wanted to rewrite the system.

‘Accountability Systems Are There To Ensure Kids Are Learning’

But what if designing an accountability system isn’t like baking cookies? What if it’s more like buying a car? Where you might care most about one or two things, such as the gas mileage or safety rating or leather seats?

That’s the analogy Jim Stergois, executive director of the Pioneer Institute, uses to describe Massachusetts’ accountability system. The state is known for its high-performing schools, but instead of issuing letter grades, the state releases all kinds of school-level data — test scores, class sizes, even student-to-computer ratios. Stergois says local media outlets then could create their own school ratings guides.

“It’s like what happens in the car industry when Consumer Reports or Popular Mechanics or these people say, ‘This Ford model is absolutely excellent, this Honda is absolutely excellent,'” says Stergois. “They’ll explain to you how they rated it. I think that’s a far better way for people to get engaged.”

Stergois says the cornerstone of any accountability system is transparency. He says the problem with assigning A-F letter grades to schools is officials can change or adapt the metrics behind closed doors — like what happened in Indiana.

—Jim Stergois, Pioneer Institute

“From the emails, it seems like there were three individuals that were primarily responsible for rejiggering grades given to schools,” says Stergois. “That in itself raises questions about objectivity.”

In total, 13 charter schools saw their letter grades improve as result of Bennett’s staff tinkering with the accountability metrics. But Indiana State Teachers Association President Teresa Meredith wonders if the independent review might reveal other schools that were negatively impacted.

“In the end, the charter who didn’t have such a good grade, got what it needed in terms of the formula to make it look better than it really should have,” she says. “We’ve got to make sure in the new system, that can’t happen. That cannot happen.”

She says Indiana needs to hold off assigning letter grades until it’s clear how many schools were potentially harmed.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download