How Science & Social Studies Teachers Are Transitioning To The Common Core

Elle Moxley / StateImpact Indiana

Cathedral High School English teacher Melinda Bundy used to teach a research paper unit on the legends of King Arthur, but she's now using President John F. Kennedy's inauguration speech. Bundy made the switch because the Common Core State Standards require 70 percent of the texts high school students read come from nonfiction.

Over the next several months Indiana lawmakers will review a set of nationally-crafted academic standards known as the Common Core. Indiana signed on to the standards in 2010, but now some parents and policymakers want out.

One of their concerns is the standard’s requirement that 70 percent of what high school students read come from nonfiction. But it’s unlikely the nonfiction requirement will go away because state law dictates whatever standards Indiana ends up with be modeled after the Common Core.

The idea is students should be reading more nonfiction in all classes, not just language arts. Yet some English teachers are skeptical their colleagues who teach subjects in which students don’t take statewide tests will take up the challenge. But Jeffrey Franklin, a social studies teacher at Mooresville High School, is already working to incorporate the Common Core in his classroom.

“Students need to read more complex texts that are going to be reflective of what they’re going to do outside of high school,” says Franklin. “That’s really the emphasis of the college- and career-readiness.”

- How Common Core Affects Non-Tested TeachersStateImpact Indiana‘s Elle Moxley explains how a requirement that high school students read more nonfiction may be blurring the lines between disciplines.Download

Why Some English Teachers Are Changing What They Teach

Let’s start with Melinda Bundy, the ninth grade English teacher at Cathedral High School we introduced you to earlier this year. She used to teach a unit on the legends of King Arthur, but feeling the pressure to incorporate more nonfiction into her curriculum because of the Common Core, this year she decided to teach a historical document and landed on John F. Kennedy’s inauguration speech.

Elle Moxley / StateImpact Indiana

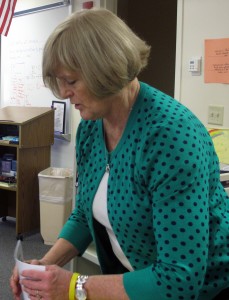

Melinda Bundy teaches ninth grade English at Cathedral High School in Indianapolis.

“I didn’t want to teach the constitution, I didn’t want to teach the Declaration of Independence,” Bundy told StateImpact in January. “Then his inauguration speech came up under historical documents. I adored JFK. I lived through his administration. I sat glued to the TV and watched everything about his assassination.”

So this year Bundy’s students wrote papers on the space race, the civil rights movement and other prominent issues in 1960s America during Kennedy’s administration.

One student calls “dibs” on a new book that’s come in from the library on his topic, the Cuban missile crisis.

But the sophomores Bundy taught last year were less enthusiastic when she poked her head into their 10th grade English classroom to tell them about the switch.

“Instead of Arthurian legend this year, we’re doing president Kennedy,” says Bundy.

“No!”

“Is that a joke?”

“That was my favorite subject!”

“I’m so jealous!” says one student. “That’s going to be so easy.”

But the architects who wrote the Common Core would disagree. They say students need to know how to read informational text if they’re going to be college- and career-ready — that’s the whole reason for the Common Core. English teachers aren’t supposed to scrap much-beloved literature to make way for nonfiction. But practically speaking, Bundy says the burden falls to the teachers administering end of course assessments and other state tests.

“The ECA is all nonfiction. They’re given an essay to read, and if we don’t cover it in English, it’s on the English part of the ECA, our kids are going to fail,” she says. “You can’t totally disavow that we’re responsible. We are.”

How Common Core Fits Into High School Social Studies

In addition to teaching social studies at Mooresville High School, Jeffrey Franklin is part of the Indiana Educator Leader Cadre, a group helping design new standardized tests aligned to the Common Core. Even though the next generation of assessments will primarily test math and English language arts, Franklin says he still shares in the responsibility of preparing students to succeed.

—Jeffrey Franklin, Mooresville High School social studies teacher

“It’s going to take people awhile to kind of get used to it and start realizing that my class actually supports science,” he says. “My government students can do something that’s going to make their English class and their literature skills more enriching.”

Requiring more nonfiction? “It’s a practical matter,” he says.

Franklin says if students are reading “To Kill A Mockingbird” in their English class, he can use historical documents to teach common themes of the civil rights struggle. But getting to that point will require educators to rethink how they teach.

“For many times in the high school environment, we get compartmentalized in our little worlds of departments, and we forget that there are other teachers who share similar interests, and we really don’t collaborate as much with them as we should,” says Franklin.

How Science Teachers Are Preparing For New Standards

Chemistry teacher Kim Zook is the science department chair at Mooresville High School. Even though the state legislature has paused implementation of the Common Core pending a thorough review, Zook says science teachers are looking ahead to the next set of standards they’ll be expected to teach.“There’s just this general feeling out there: Where’s it going to go with science?” says Zook.

Zook says one of the challenges with adopting high school science standards is that states don’t require schools teach biology, chemistry and physical science in the same order. But she thinks teachers in non-tested subjects may still have something to learn from new standards.

“One thing that Common Core really does is practically apply these skills,” says Zook. “That’s what happens when students take their English to social studies and their math to science.”

Zook likes the fact that the Common Core emphasizes problem-solving skills and project-based learning, especially in the lower grades. Too often, she says, science is put on the back burner in elementary school, and that can leave students struggling when they reach her classes.

“There for awhile, there were a lot less comfortable with project-based work because elementary teachers were getting ready for a test, and they threw out some of the big projects kids used to do,” says Zook. “Science fair went by the wayside, international fair went by the wayside, and kids became a lot less adept at putting that whole big project together.”

Zook says it doesn’t matter if Indiana ultimately ends up with the Common Core State Standards or other, similar standards, so long as they prepare kids for college and career.

Why Change Is Coming, Even If It Isn’t The Common Core

Franklin says the bottom line is Indiana will get new standards, even if it doesn’t ultimately adopt the Common Core.

“You can get in or get out, but the state will have to develop some form of national, college and career assessments at some point,” he says.

If Indiana doesn’t adopt college- and career-ready standards, the state would lose its federal No Child Left Behind waiver, which could cause even bigger problems than the fight over the Common Core.

Indiana had just started aligning its standards for social studies to the Common Core when state lawmakers paused implementation of the new standards. Franklin says that means many teachers will have to wait a little longer for the resources they need to successfully implement new standards in non-tested subjects.

“To really look at the breadth of the entire field of social studies, there’s not resources in every class to be able to pick up the broader teaching shifts,” says Franklin. Creating and identifying those resources, he adds, “is going to be the biggest difference between successfully implementing a new level of education as opposed to just saying, well, this is a new assessment.”

Got a question about the Common Core? We’re still taking your Core Questions. Connect with us via Facebook, Twitter or email and let us know what questions you have about Indiana’s Common Core pause.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download