Why Holding Back Third Graders Who Fail Reading Tests Isn't A Silver Bullet Strategy

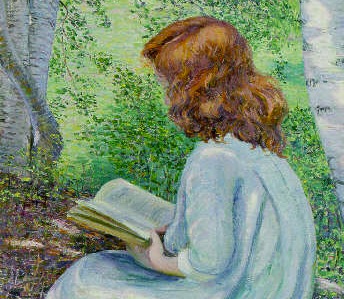

Kyle Stokes / StateImpact Indiana

Two third grade students at Bloomington's Clear Creek Elementary play 'Concentration' as part of teacher Amy Swafford's lesson on syllables.

Retention for students who don’t pass third grade reading exams works best when used in concert with other intervention strategies, according to a policy brief released Thursday by the Center on Children and Families at The Brookings Institution:

Policies encouraging the retention of students who have not acquired basic reading skills by third grade are no substitute for the development of a comprehensive strategy to reduce the number of struggling readers. Yet the best available evidence indicates that policies that include appropriate interventions for retained students may well be a useful component of a comprehensive strategy. There is nothing in the research literature proving that such a practice would be harmful to the students who are directly affected, and some evidence to suggest that those students may benefit.

We’ve written before that there isn’t a lot of research on the success of reading retention programs. You can probably find support for your opinion regardless of how you feel about Indiana’s policy of retaining third graders who don’t pass the state IREAD-3 exam.

Harvard professor Martin West, the brief’s author, does a nice job of summarizing the research that is available — both observational studies criticizing retention and the more recent results of Florida’s reading policy. He writes:Critics point to a massive literature indicating that retained students achieve at lower levels, are more likely to drop out of high school, and have worse social-emotional outcomes than superficially similar students who are promoted. Yet the decision to retain a student is typically made based on subtle considerations involving ability, maturity, and parental involvement that researchers are unable to incorporate into their analyses. As a result, the disappointing outcomes of retained students may well reflect the reasons they were held back in the first place rather than the consequences of being retained.

Some highlights of the report:

- Thirty-two states and the District of Columbia have third grade reading policies. Fourteen include some kind of retention component, though they vary on who is retained and how.

- On average, it costs $10,700 per year to educate a student each year. Even if just two percent of all students are retained annually, the costs add up to more than $12 billion. The states aren’t the only one taking a financial hit. West points out students lose a year or more of income by entering the workforce later.

- In 2003, the first year of its new reading program, Florida retained about 22,000 students — 14 percent of all third graders and more than four times as many as the year before. The number of students retained has fallen in subsequent years as fewer students fail to meet the cut off.

- A study followed the first group of third graders retained in Florida for the next six years. While the students showed tremendous gains after two years, often outperforming their peers on standardized tests, those short-term gains disappeared over time.

So does retention work or not? In a panel discussion sponsored by The Brookings Institute, early education advocate Karen Schimke explains why it’s so hard to research retention in the first place: You can’t promote and retain the same child. So even a well-designed study can’t necessarily control for other factors in students’ lives that may change their outcomes.

The debate is worth a watch if you’re interested in what’s happening here in Indiana with the IREAD-3. The experts touch on the important of early education (Hint: Learning to read starts before students enter third grade, and even before they start school) in a successful reading policy.

“Test-based promotion policies are not being presented by anyone on the panel today as a silver bullet solution, as the only thing we need to do to address early grade reading skills,” says West before the discussion. “We need comprehensive strategies.”