Why One English Teacher Is Dropping The Legends Of King Arthur For The Life Of JFK

Elle Moxley / StateImpact Indiana

Melinda Bundy teaches ninth grade English at Cathedral High School in Indianapolis.

Melinda Bundy has taught at Cathedral High School in Indianapolis for 39 years. Students in her ninth grade English class usually spend February immersed in King Arthur, studying legend and learning to write research papers.

Last week her ninth graders learned to take research notes and cite bibliographical information. But this year they aren’t studying Arthurian legend — they’re learning about John F. Kennedy’s America.

Bundy sent this note home to parents explaining why she made the switch:

We are beginning the research paper for English 9H. I have changed the scope of the project because when I looked at the Core Standards, I saw that one of the standards was to analyze a historical document. I have chose President John F. Kennedy’s inauguration speech as the basis of the paper. The students have watched the video of the inauguration, read the speech, analyzed the content, and discussed it in class. Now they are going to research the ’60s and find out what was actually going on in the U.S. as well as the world during Kennedy’s administration. Then they will chose one event/issue/problem and relate it to President Kennedy.

Why Some English Teachers Feel Responsible For Nonfiction

Bundy loved teaching Arthurian legend. But she says with Indiana’s transition to the Common Core, a set of new academic standards adopted by 46 states and the District of Columbia, she’s had to incorporate more nonfiction into her curriculum to prepare students for state tests.

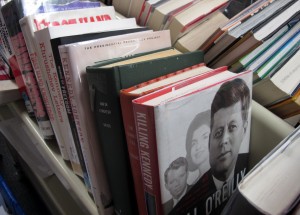

Elle Moxley / StateImpact Indiana

A student writes bibliography information on a notecard. Ninth graders in Melinda Bundy's English class are researching John F. Kennedy's presidency.

The new standards require 70 percent of everything high school students read be nonfiction. Common Core architects say teachers in all subjects should incorporate more informational texts.

But in practice, Bundy says that burden falls on English teachers preparing students for end-of-course assessments.

“The ECA is all nonfiction. They’re given an essay to read. If we don’t cover it in English, and it’s on the English part of the ECA, our kids are going to fail,” says Bundy. “We can’t totally disavow that we’re responsible. We are.”

Bundy likes teaching Kennedy’s inauguration speech. There’s an endless number of topics students can explore in 1960s America — the civil rights movement, the Cuban missile crisis, the space race, the Cold War, among others — and the library keeps sending down more resources for students to use. Yet Bundy still feels a pang for some of the subjects she used to teach.

“I don’t teach short stories anymore. I love short stories. But we read biographies and autobiographies now,” she says.

Bundy says swapping kings for the Kennedys is the biggest change she’s made to her literature list. She’s still teaching “Antigone,” “Romeo and Juliet” and other classics.

How The Common Core Fits Into Advanced Placement Classes

Kathy Keyes teaches sophomore English at Cathedral, mostly AP Literature and Composition. She says the Common Core standards won’t change much in Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate classes.

“In sophomore English, we actually read quite a bit of nonfiction because we teach American literature,” says Keyes. “So we begin by reading the early documents. We read the Declaration of Independence, the speeches of the revolutionary writers, we read Ben Franklin, so quite a bit of our reading is already nonfiction.”Keyes says she’s not sure the push toward nonfiction began with the Common Core. She says Indiana’s end-of-course assessments have long included informational texts students are expected to read and comprehend.

So Keyes tries to weave nonfiction and literature into the same unit.

“My sophomores are currently working on their research paper, and they’re writing on a poem,” says Keyes. “But they’re looking at nonfiction. They’re looking at biographical information, they’re looking at literary criticism of the writer, so they’re using those nonfiction sources to write about a work of fiction.”

What New Standards Mean For Private Schools Like Cathedral

As a department, the English teachers at Cathedral have been working to develop common assessment tools like final exams. All students are on a college prep track and take the same finals. Teachers with honors or AP sections can add additional questions.

Elle Moxley / StateImpact Indiana

Melinda Bundy used to teach a unit on the legends of King Arthur, but because the new Common Core standards require more nonfiction, she's now using President John F. Kennedy's inauguration speech.

Bundy and Keyes both say people are surprised to hear Cathedral, a private school, has to align with the Common Core. The school participates in Indiana’s voucher program — a little less than 4 percent of the school’s 1,252 students receive state money — and students take the same standardized tests they would at public school.

Keyes says the biggest change with Common Core isn’t nonfiction but curriculum mapping, the process by which teachers ensure their lesson plans are aligned with the new standards.

“We sit down, describe what we teach, our strategy for teaching it, the assessments that we use and then correlating those to the standards of those Common Core,” says Keyes. “What it’s really done for me, as an AP teacher, is validating many of the assignments I’ve already used are things the Common Core is expecting and requiring.”