Here's What A 'D' School Looks Like: Inside Indiana's School Turnaround Process

Elle Moxley / StateImpact Indiana

Rockville Elementary School parents listen as Principal Jeff Eslinger explains what the school is doing to improve its letter grade from the state. The school received a D for the 2011-12 school year.

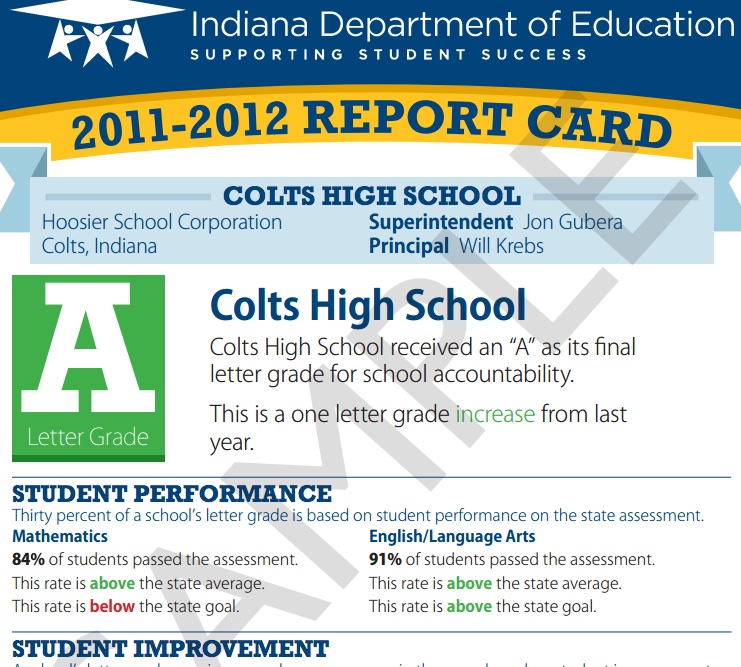

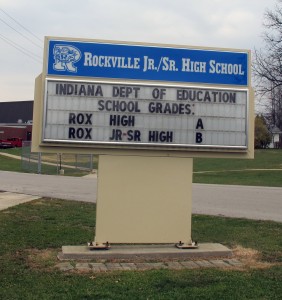

The sign outside Rockville’s high school and junior high boasts the schools’ letter grades: An A and a B. But down the road at the elementary school, Principal Jeff Eslinger calls a meeting to tell parents the bad news: Their school received a D.

Indiana schools that receive a D or an F from the state must work with the Department of Education to develop a school improvement plan. The idea is that state support now will help the schools avoid further intervention in the future.

But sometimes the difference between a C and a D can be one student’s score. That’s what happened in Rockville.

- 'I'm Really Looking For A Sense Of Urgency'StateImpact Indiana‘s Elle Moxley reports on what turnaround efforts look like at Indiana schools that received a D in the state’s accountability system.Download

Elle Moxley / StateImpact Indiana

Rockville High School received an A from the state and the junior high received a B. Indiana uses a different accountability system for high schools than it does for elementary schools.

Principal Eslinger tells parents that the problem is scores on state standardized tests. About 69.5 percent of the school’s students passed the ISTEP+ last year, just shy of the statewide pass rate of 71 percent.

But where Rockville Elementary fell short is in showing improvement in those test scores, part of a complicated calculation called the “growth model.”

Scores on the English language arts portion of the ISTEP+ went up 11.4 percent in Rockville. But that’s not the kind of growth the state’s accountability model measures. Instead, it compares student performance year over year to their peers across the state. Enough students showed “low growth” that the school lost a point, dropping the school’s letter grade from a C to a D.

Principal Eslinger explains all of this to parents. “What killed us? Right here.” If more than 39.8 percent of students show low growth, the school loses a point. Last year 40.6 percent of students in Rockville showed low growth. “Eight-tenths of a percent. That’s one student.”

During School Turnaround Visits, IDOE Looks For ‘Urgency’

Parent Candy Bowser says she feels better after hearing Eslinger explain Rockville’s letter grade. But nobody wants their kid to go to a D school.

“Why are we in a school that’s a D level when we have other schools in the county that are an A or B?” she says.Nearby Turkey Run Elementary got an A — and because state funding follows the student in Indiana, it’s easy for parents to switch schools if they aren’t satisfied. That’s why Eslinger doesn’t just want to tell parents why Rockville Elementary got a D. He also wants them to know what he’s going to do to make sure it doesn’t happen again. There’s a school improvement plan, and a specialist working with teachers to design curriculum.

Then there’s IDOE turnaround specialist Ben Carter. It’s his job to see what kind of progress Eslinger and other staff at Rockville are making to transform the school.

Carter visits Rockville about a week after Eslinger’s parent meeting. He walks from classroom to classroom, taking notes on teachers and students. He works with focus and priority schools across the state. That means they received a D or an F. About 18 percent of Indiana schools are targeted for intervention because of their accountability score.

Elle Moxley / StateImpact Indiana

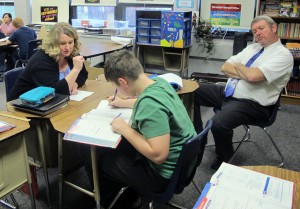

Principal Jeff Eslinger, right, watches as a sixth grade teacher helps a student with a math lesson. A turnaround specialist from the Indiana Department of Education visited Rockville Elementary to track implementation of the school improvement plan.

A former math teacher, Carter asks a sixth grader to explain a basic geometry problem. The students are learning about rotations and translations.

“So we would take it from here” — the student points to a shape sketched in pencil on graph paper — “move it on its side, and upside down.”

“Getting pretty good at it?” Carter asks.

“It’s tougher than it seems, but yeah.”

At the end of the lesson, the teacher collects the assignment and dismisses students to their social studies class. Carter makes a note on his clipboard.

“So I’m really looking for a sense of urgency,” he says. “The pacing of a lesson. That there’s no instructional minutes wasted.”

Schools Get Suggestions To Aid Improvement Process

Later, in a meeting with Rockville staff involved in the intervention, Carter says the sixth graders took too long to move from their math lesson to their social studies class.

“Obviously, I only saw a short sample, but what I did see, from activity to activity, the transitions could just be ramped up,” he says. “How can we utilize those instructional minutes to the best of our ability, not wasting a single second of time?”

He suggests using timers in the classroom — a countdown clock to let students know when they need to be in their seats, ready to learn. He tells Rockville’s staff small fixes can make a big difference.

“Mr. E and I talked. What are we, like two students away from being a C and not even having this visit?” says Carter.

Why It’s Hard To Say If Efforts Will Improve School’s Grade

Forget signs. Eslinger says if Rockville Elementary gets an A or a B next year, he’s putting it on top of the water tower in town. It’s his first year at the elementary school after transferring from Rockville High, an A school.

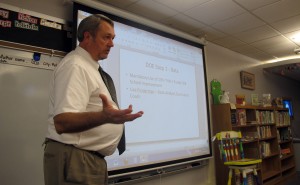

Elle Moxley / StateImpact Indiana

Rockville Elementary School Principal Jeff Eslinger explains to parents how the state calculates school letter grades.

The demographics of the two schools are the same. There are few jobs in Parke County, and about three-quarters of students in Rockville qualify for free or reduced lunch — nearly twice as many as five years ago.

But the state accountability system for high schools is different, awarding bonus points for offering AP classes or boosting the graduation rate. Elementary schools can’t get those same bumps, leaving Eslinger skeptical that timers will fix problems caused by growing poverty. Still, he’ll do what the DOE asks.

“But whether we agreed with or disagreed with the grade we have, obviously we have to react to it,” he says.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download