What's Next For Third Graders Who Didn't Pass Indiana's Reading Test

Kyle Stokes / StateImpact Indiana

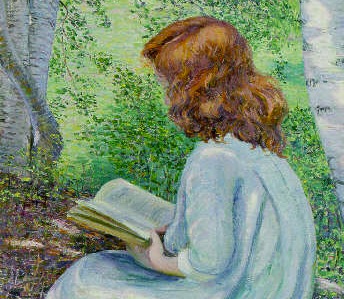

Ethan Brown, a third grader in Franklin Community Schools, did not pass the IREAD-3 exam. His mom, Jamie Abbett (right), says it isn't fair for her child to have to worry about one test. State officials say struggling readers need an intervention.

Ethan Brown needed a score of 446 to pass Indiana’s new third grade reading test. But last month, he found out he’d scored a 443.

“I started crying and telling myself I was stupid because I didn’t pass that test,” Ethan, 9, remembers.

84 percent of Indiana third graders passed the IREAD-3 exam last March. More than 11,700 Indiana third graders who did not, however, must retake the test in June or July.

Ethan, a third grader at Webb Elementary School in Franklin, has trouble focusing sometimes and takes medicine for ADHD.

—Jamie Abbett, Franklin parent

But because he’s not an English language learner or a special education student, Ethan must pass his retake this summer. If he doesn’t, state policy requires he take all statewide tests as a third grader next year.

In other words, in all likelihood, he won’t advance to fourth grade if he doesn’t pass the IREAD-3 this summer.

“I want to move on. I don’t want to be stuck in third grade. I don’t want to be held back. I want to go on to the next grade,” Ethan says.

But what happens to Ethan next year is still, to a degree, an open question. The state points to areas of the new policy that give local districts options in deciding what to do with students like Ethan, should he not pass again.

Teachers and district officials, though, say they still feel as though the new policy limits their ability to decide what’s best for the students who fail the IREAD-3.

- Bennett: 'We Have To Stop Lying To Children'StateImpact Indiana‘s Kyle Stokes speaks with a Franklin third grader who didn’t pass the IREAD-3, his mom, and the state officials who say it’s their duty to step in when students are struggling.Download

Hands Tied Or Hands Freed?

Indiana’s new policy is rooted in the idea that schools must identify the students who need the most help with their reading skills. Once identified, teachers can then step in to provide specialized or one-on-one reading instruction or, “as a last resort,” hold the student back.

State superintendent Tony Bennett says third graders who cannot read need help, or they’re likely to lag behind their peers for the rest of their academic careers.

“We have to stop lying to children,” Bennett told reporters at a press conference in his statehouse office on May 15. “This involves having hard conversations with children and their parents.”

The policy does allow schools to handle retention in different ways. Students who do not pass the IREAD-3 could theoretically be educated in a blended Grade 3-4 classroom, or attend subjects other than reading in a fourth grade classroom.

But even state officials say these scenarios are unlikely. The best way for a student to prepare for a third grade statewide test, many educators say, is to spend a year in a third grade classroom.

Franklin Community Schools curriculum Deb Brown-Nally says the state’s tough line on reading has limited the authority of educators in her district to make decisions. She tells StateImpact her district has had processes in place to handle a struggling student since before the state implemented the new policy:

I believe the philosophy behind all this is very valid and very good. We don’t want to send kids on who aren’t ready, but my experiences at Franklin Community Schools is that we haven’t done that. We’ve tried to provide intervention programs at the outset. We’ve had the hard conversations. We have retained kids. But I like to believe the professionals are making the decision along with the parents — who know the child better than anybody — they’re making that decision together, rather than a one-day, one-hour test.

Kyle Stokes / StateImpact Indiana

Ethan Brown, 9, plays a video game in his Franklin home. His teachers are beginning a remediation program to prepare him to retake the IREAD-3 in late June.

Retention As Intervention

Opponents of the state’s reading policy say retention is not the best intervention for a struggling student.

Bloomington teacher Lee Heffernan, a literacy coach at a high-poverty elementary school, says that intervention can actually break the spirits of a struggling student. As she told StateImpact earlier this month:

A big part of a teachers job is reinforcing that reading and writing is part of their identity; to reassure them, ‘You are a reader, you are a writer, you can do this, you know the strategies to tackle this puzzle that we’re giving you’…

It is a big identity issue. If you’re not going on to fourth grade with your peers, that’s very disorienting and troubling for a kid. It’s really high pressure to stay with your peer group and be part of the community, it’s kinda harmful to a kid’s identity to say, ‘Well, you weren’t really a reader or a writer,’ you aren’t gonna be a fourth grader.

—Tony Bennett, state superintendent

Derek Redelman, the vice president for education policy at the Indiana Chamber of Commerce, says he agrees with the idea that simply repeating the third grade is not an effective way to help a struggling reader.

But Redelman says retention can work in the right context. As he told StateImpact last week, the IREAD-3 is part of a much more cohesive state policy that makes reading a priority in the early grades:

I think what DOE is putting together is a whole package. They have been promoting particular curriculum approaches that have evidence backing up their success. They have urged this 90-minute reading block as one of the issues, but not the only one. They have created several diagnostic testing opptys so that teachers and schools can monitor the progress that their students are making. I think it’s a whole set of approaches.

And I do think the retention issue really is an absolute last restort. I don’t think anywhere in DOE’s plan have they said, ‘Hey, we’re going to test at the end of the third grade then by golly we’re gonna hold you back.’ They’re doing a whole bunch of stuff leading up to that and I think anyone who portrays this purely as a retention program either is not informed or is trying to distract from what’s really going on.

Franklin Schools curriculum director Deb Brown-Nally says the state has offered guidance to districts. But she says third grade is probably too late to retain a student.

What’s Next For Ethan

Ethan’s mom, Jamie Abbett, says she knows extra reading help this summer will be good for her son. But she feels like the state’s policy has left her without much say over Ethan’s education.

“It breaks my heart that my child think’s he’s stupid because of one test,” Abbett says, adding, “It’s not fair to a nine-year-old to have to feel that way about not passing — or even just to have to worry about failing.”

Most teachers say Ethan came so close on the IREAD-3 last time that he’ll surely be able to pass his retake. Ethan hopes they’re right.

“I hope that I will pass this test, because I really want to go on to the next grade and enjoy my summer,” Ethan says.

He’ll enjoy it as much as he can — he was going to spend a summer with his grandma in Florida. Now, he’ll have to wait until he retakes the test.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download